Sporting Space, Sacred Space: a Theology of Sporting Place

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recruitment Pack Dear Applicant

US together we can do it recruitment pack Dear Applicant, Thank you for showing an interest in our organisation and the role for which we are currently advertising. As President of our Union, I am incredibly proud to lead such a passionate and active organisation which has a clear positive impact on students’ lives at Lancaster University. This pack should give you a clear idea of what we are all about and where we see our future. Having motivated and enthusiastic staff who want to deliver for the organisation is critical to this. As well as being able to achieve within the students’ union, you will find that LUSU has a friendly and lively environment to work in. This includes working with experienced professionals, recent graduates and students; all of which culminate in a hub of ideas and energy. I would encourage you to find out more about us and I look forward to meeting some of you during the interview process. Ste Smith, LUSU President 2012-13 “ensuring representation, support, opportunities and services for Lancaster students” what lusu does We provide a mix of representation, opportunities, activities and services for Lancaster students. We are a not-for-profit, charitable organisation so any money we make through our commercial activity is ploughed straight back into offering our members more and better services. We look after all of the societies and sports clubs on campus, provide hundreds of volunteering opportunities both here and globally plus we put on big events like Roses and Grad Ball . We run a broad base of commercial operations from a nightclub to retail units. -

John Hedley Brooke Interviewed by Paul Merchant C1672/8

NATIONAL LIFE STORIES ‘Science and Religion: Exploring the Spectrum’ John Hedley Brooke Interviewed by Paul Merchant C1672/8 This transcript is copyright of the British Library Board. Please refer to the Oral History curators at the British Library prior to any publication or broadcast from this document. Oral History The British Library 96 Euston Road NW1 2DB 020 7412 7404 [email protected] IMPORTANT Access to this interview and transcript is for private research only. Please refer to the Oral History curators at the British Library prior to any publication or broadcast from this document. Oral History The British Library 96 Euston Road London NW1 2DB 020 7412 7404 [email protected] Every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of this transcript, however no transcript is an exact translation of the spoken word, and this document is intended to be a guide to the original recording, not replace it. Should you find any errors please inform the Oral History curators ([email protected]) The British Library National Life Stories Interview Summary Sheet Title Page Ref no: C1672/08 Collection title: ‘Science and Religion: Exploring the Spectrum’ Life Story Interviews Interviewee’s surname: Hedley Brooke Title: Professor Interviewee’s John Sex: Male forename: Occupation: Historian of science Date and place of birth: 20th May 1944, and religion Retford, Nottinghamshire, UK Mother’s occupation: Father’s occupation: teacher teacher Dates of recording, Compact flash cards used, tracks (from – to): 21/5/15 (track 1-3), 26/06/2015 (track 4-5), 22/09/2015 (track 6-7), 20/10/2015 (track 8-9), 08/12/15 (track 10-11), 02/02/16 (12-14), 26/04/16 (track 15) Location of interview: Interviewees' home, Yealand Conyers near Lancaster and the British Library Name of interviewer: Paul Merchant Type of recorder: Marantz PMD661on compact flash Recording format : audio file 12 WAV 24 bit 48 kHz 2-channel Total no. -

The Study of Religion in the UK in Its Institutional Context

KIM KNOTT The Study of Religion in the UK in its Institutional Context THE STUDY OF RELIGION IN THE UK IN ITS INSTITUTIONAL CONTEXT How has the study of religion in the UK been shaped by its institutional contexts? Consideration is given to the Christian and secular foundations of universities and higher education colleges, the relationship of theology and religious studies, and the impact of institutional structures and drivers associated with teaching and research. The formation of ‘TRS’ as an instrumental and contested subject area is discussed, as is the changing curriculum. Research on religion is examined in relation to new institutional pressures and opportunities: the assessment of university research and the public funding of research. The importance of the impact agenda and capacity building are illustrated. The nineteenth century roots of religious studies (Religionswissenschaft) in Britain lie in the work of scholars such as Max Muller, E.B. Tylor, J.E. Carpenter and T.W. Rhys Davids. Britain hosted the third IAHR Congress in 1908 in Oxford, but the British Association for the History of Religions (later to become the British Association for the Study of Religions) was not founded until 1954, with E.O. James and Geoffrey Parrinder as two of its founder members. Although a Manchester Chair of Comparative Religion was established in 1904, and a Department of Theology and Religious Studies was opened at the University of Leeds in the 1930s, it was not until 1967 that the first autonomous non-theological Department of Religious Studies was opened, at Lancaster University, with Ninian Smart as its first Chair. -

70S Pro-Choice Plaintiff in Roe V. Wadeto Speak on New Pro-Life

Dead Week = Deadlines Getting I.V. Up to Code Mickey Mouse Is Not Smiling . Study for all your important finals, for they could be À longtime Isla Vista resident con The UCSB men’s basketball team your last! tends that the proposed mandatory ended its season on a sour note in an housing inspection program is overtime loss against Pacific at' the simply not feasible. Anaheim Convention Center Thursday. See Opinion p.4 See Sports p.8 Friday jï M Sunset March 9, 2001 6:01 p.m. Tides ^ www.ucsbdailynexus.com High:9:06 a.m. Low: 3:43 p.m. Volume 81, No.94 Two Sections, 12 Pages 70s Pro-Choice Plaintiff in Roe v.Wade To Speak on New Pro-Life Stance By Ladan Moeenziai cuss the transition from law. The lawsuit was Staff Writer pro-choice to her current appealed to the U.S. pro-life beliefs, despite the Supreme Court, and its pivotal role she played in decision legalized abortion Norma McCorvey, legalizing abortion in the in all 50 states. “Jane Roe” in the 1973 United States. In 1969, In 1995, McCorvey United States Supreme McCorvey unsuccessfrilly publicly renounced her Court case Roe v. Wade, sought an illegal abortion involvement in Roe v. will speak in Isla Vista in Texas, and ultimately Wade and announced her Theater on Sunday at 7:30 ended up as the plaintiff in conversion to Christianity. p.m. a class action lawsuit McCorvey will dis against the state’s abortion See ROE, p.3 UC Berkeley Rally Calls for Affirmative Action Thousands of students filled Berkeley’s testers, it would be a symbolic victory; Sproul Plaza on Thursday to call for the because Affirmative Action is outlawed in return of Affirmative Action in California under the voter-passed California. -

How the New Atheists Are Reminding the Humanities of Their Place and Purpose in Society

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2018 The emperor's new clothes: how the new atheists are reminding the humanities of their place and purpose in society. David Ira Buckner University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Buckner, David Ira, "The emperor's new clothes: how the new atheists are reminding the humanities of their place and purpose in society." (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3112. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/3112 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE EMPEROR’S NEW CLOTHES: HOW THE NEW ATHEISTS ARE REMINDING THE HUMANITIES OF THEIR PLACE AND PURPOSE IN SOCIETY By David Ira Buckner B.S., East Tennessee State University, 2006 M.A., East Tennessee State University, 2008 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy -

A Racing Certainty Y

Award-winning magazine of the British and International Golf Greenkeepers Association October 2003 - £3.50 A Racing Certainty y Take a look at Nigel Mansell's Golf Course, Woodbury Park, in Devon Finance | Pay Recommendations | Construction Machinery | Saltex Review | Pesticide Legislation See us ALLOW US TO POINT OUT THE LATEST IN NEW TRACTOR TECHNOLOGY. Now you can push a tractor to the limits of performance - just by pushing a button. LoadMatch monitors transmission speed under load to prevent stalling the engine and to maximise tractor performance. (Front loader: You can scoop a full bucket, every time. Mowing: You always have the maxi- mum power on the mower deck with the self adjusting tractor speed to be able to handle 6 different grass conditions). New, electronically activated eHydro transmission reduces pedal effort by up to 70%. MotionMatch lets you match transmission response to the dif- ferent demands of mowing and loading. Cruise control makes work easier than ever. Set the speed you want by just pressing a switch. You can even add a resume, acceleration and deceleration feature, just like your car. SpeedMatch takes "creeper speed" to a new level of precision. Implement attachment? Fast as ever. Reliability: The stuff of legends. Visit your local John Deere dealer. Test drive the 24 kW - 36 kW (32 to 48 hp) 4010 Series and experience technology that cannot only activate your tractor's full capabilities - but your sense of wonder, too. (S3 NOTHING RUNS LIKE A DEERE A guide to Advertisers' Index who's who ADVERTISER TELEPHONE -

ABSTRACT the Great American Disappointment: an Introduction to the Great Disappointment Theory As a Way to Explain the Unique Ev

ABSTRACT The Great American Disappointment: An Introduction to the Great Disappointment Theory as a Way to Explain the Unique Evolutionary Processes of Socially-Guided Religion by Means of American Civil Religion Ethan Gjerset Quillen, M.A. Mentor: Douglas R. Ferdon, Ph.D. America is unique when compared to the rest of the world for many reasons, but especially so for its religion. To this, as human beings evolve socially, in the same way animal species evolve in order to seek out variable fitness toward survival, their religion follows suit. This has been particularly so in the United States where absolute religious freedom makes way for one of three processes of evolution within the American Church of Civil Religion. These three processes, Atheism, Fundamentalism and New Religious Movements, become the direction in which Americans evolve their religious beliefs in the wake of socially- guided religious disappointment. This Great Dis appointment Theory, based on the results of William Miller‟s Great Disappointment in the 19 th century, helps explain the means by which Americans, who act as individuals within an immigrant nation, are able to come together as a congregation within the American Church of Civil Religion. The Great American Disappointment: An Introduction to the Great Disappointment Theory as a Way to Explain the Unique Evolutionary Processes of Socially-Guided Religion by Means of American Civil Religion by Ethan Gjerset Quillen, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Approved by the Department of American Studies ___________________________________ Douglas R. Ferdon, Ph.D., Chairperson Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved by the Thesis Committee ___________________________________ Douglas R. -

Schedule/Results How to Follow

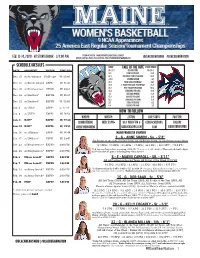

tyson mchatten - MAINE woMEN’S BASKETBALL CONTACT feb. 13-14, 2020 - at stony brook - 3/2:00 P.m. OFFICE: (207) 581-3596 | CELL: (207) 992-7746 | [email protected] @Blackbearswbb #BlackBearNation SCHEDULE/RESULTS Maine TALE OF THE TAPE stony brook DATE OPPONENT WATCH TIME/RES. 14-1, 11-1 record/conf. 10-4, 8-2 67.1 points per game 59.9 Dec. 10 at Providence FloHoops W, 62-48 52.1 opponent points per game 50.2 +15.0 scoring margin +9.7 Dec. 11 at Rhode Island ESPN+ W, 61-47 43.1 field goal percentage 39.7 33.3 3-point field goal percentage 25.3 Dec. 20 at Northeastern NESN W, 63-62 72.3 free throw percentage 66.5 34.3 rebounds per game 39.0 -1.2 REBOUND MARGIN +6.9 Dec. 22 at Hartford* ESPN3 W, 85-57 15.9 ASSISTS PER GAME 12.8 12.3 TURNOVERS PER GAME 15.6 Dec. 23 at Hartford* ESPN3 W, 52-49 9.5 Steals PER GAME 8.2 2.4 Blocks PER GAME 3.3 Jan. 2 at UNH* ESPN+ L, 57-58 HOW TO FOLLOW Jan. 3 at UNH* ESPN+ W, 76-56 WHERE: WATCH: LISTEN: LIVE STATS: TWITTER: Jan. 9 NJIT* ESPN+ W, 77-60 Island federal Web: espn+ 96.1 WGUY-FM & goblackbears. Follow: Jan. 10 NJIT* ESPN+ W, 74-51 credit union arena GoBlackBears.com com @BlackBearsWBB Jan. 16 at UAlbany* ESPN+ W, 66-48 MAINE PROJECTED STARTERS Jan. 17 at UAlbany* ESPN+ W, 63-47 3 - G - ANNE SIMON - So. -

Downloaded on 2018-08-23T18:34:14Z Journal of the Irish Society for the Academic Study of Religions 3 (2016) 27 © ISASR 2016

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Cork Open Research Archive Title Brian Bocking and the defence of study of religions as an academic discipline in universities and schools Author(s) Cush, Denise; Robinson, Catherine Publication date 2016 Original citation CUSH, D. & ROBINSON, C. 2016. Brian Bocking and the defence of study of religions as an academic discipline in universities and schools. Journal of the Irish Society for the Academic Study of Religions, 3(1), 27-41. Type of publication Article (peer-reviewed) Link to publisher's http://jisasr.org/ version Access to the full text of the published version may require a subscription. Rights (c)2016, The Author(s). Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/3799 from Downloaded on 2018-08-23T18:34:14Z Journal of the Irish Society for the Academic Study of Religions 3 (2016) 27 © ISASR 2016 Denise CUSH & Catherine Robinson Brian Bocking and the Defence of Study of Religions as an Academic Discipline in Universities and Schools ABSTRACT: In this article we will explore the contribution made by Brian to establishing and defending study of religions as a discipline in its own right and argue for the importance of a holistic and polymethodic approach to studying religions as the most appropriate way forward for programmes for undergraduates at university and students in schools. We will include the major contributions made by Brian in the institutions in which he has taught, with particular attention to our own Bath Spa University. The title “study of religions” - contributed by a student of Brian's - implies something about both content and methodology as well as his attitude towards students as co-participants and potential colleagues. -

Original Print

Spring 2001 Published by the American Academy of Religion Vol. 16, No.2 INSIDE ANNUAL MEETING REGISTRATION THIS ISSUE PACKET see inside Annual Meeting News Registration News . .2 www.aarweb.org/annualmeet Important Dates . .2 What’s on in Denver . .9 A look back at Nashville . .9 Second Chairs Annual Meeting A look at membership surveys about the Workshop Announced 3 Annual Meeting . .25 Evaluating Teaching chosen as theme Around the Quadrangle . .6 Census Enters Analysis Stage 3 In Memoriam . .10 Field data to become “information” NEW In the Field Teaching Award Recipient Announced 5 Now online . .10 Eugene Gallagher, Connecticut College Features Member Committees Meet and Act 11 Department Meeting . .23 Spring meetings advance the work of the Academy A conversation with Steve Dunning, Chair, Department of Religious Studies, University of Pennsylvania Religion Scholars Receive National Member-at-Large . .12 Arts and Humanities Medal 5 Claude Welch on the first census of religion Robert Bellah and Edmund Morgan honored and theology programs The Public Interest . .19 Courtney S. Campbell on cloning Find Religion @ _________ 4 From the Student Desk . .12 New resource mounted on www.aarweb.org Suzanne E. Schier, Vanderbilt University, on AAR gatherings Regional Development Grant Research Briefing . .17 A conversation with Linda Barnes of the Opportunities Sought 4 Boston Healing Landscape Project “Blame Canada:” Defending the Humanities . .6 Rebecca S. Chopp: . .15 Special Supplement Scholar, administrator, and volunteer and... AAR series from Oxford University Press . .7 Spotlight on Teaching Religion and Music Journalist as Scholar . .16 Joyce Smith talks to Kenneth Woodward, Newsweek magazine Ninian Smart, 1927-2001 . -

Extensions of Remarks E843 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

May 6, 1997 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð Extensions of Remarks E843 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS COMMEMORATING THE In the words of Elie Wiesel, Holocaust survivor seas Long and Short Tour Ribbon, the Air HOLOCAUST and honorary first chairman of the Holocaust Force Longevity Service Award, the Small Council, [We cannot] allow anyone or anything Arms Expert Marksmanship Ribbon, the New HON. DONALD A. MANZULLO to deprive [us] of the great, great miracle York State Commendation Medal and the New OF ILLINOIS which renders a human being sensitive to oth- York Conspicuous Service Cross. IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ers.'' Upon completion of such exemplary service Mr. Speaker, 1997 marks the 3,300th year to our Nation, I commend Chief Dix and wish Tuesday, May 6, 1997 of the establishment of the city of Jerusalem. him well in retirement. Mr. MANZULLO. Mr. Speaker, I am honored This year is also the 30th anniversary of the f to be able to take this opportunity to com- reunification of Jerusalem after the Six-Day memorate the more than 8 million peopleÐ6 War. While there will be ceremonies recogniz- TRIBUTE TO THE DEDICATION OF million of whom were JewishÐwho a little ing these events, we must not forget to pause THE BAUMGARTNER HOUSE HIS- more than a half century ago were brutally, again this year in solemn remembrance of TORICAL DESIGNATION PLAQUE deliberately, and systematically exterminated Yom Ha'Shoah. I urge all of us to take time in a state-sponsored effort to annihilate their out to remember those who died in the Holo- HON. DAVID E. -

Lancaster University Annual Report and Accounts 2011

LAncAsteR UniveRsity AnnUAL RepoRt And AccoUnts 2011 Lancaster University 1 1 Lancaster 0 2 LA1 4YW s t United Kingdom n u o c T: +44(0)1524 65201 c A www.lancs.ac.uk d n a ISBN 978-1-86220-290-0 t r o p e R y t i s r e v i n U r e t s a c n a L Lancaster University has been awarded the Carbon Trust Standard after taking action on climate change by reducing carbon emissions. The University has made an overall reduction of 245 tonnes of carbon or 0.9% averaged over the past three years. Lancaster University 1 Contents Vice-Chancellor’s review 2 Pro-Chancellor’s review 4 High notes of the year 6 A global university 12 Awards and distinctions 18 Advancing knowledge through research 30 Key facts and figures 42 Financial Statements 46 Operating and Financial Review for the year ended 31 July 2011 48 Statement of Corporate Governance 56 Independent Auditors’ Report to the Council of Lancaster University 61 Statement of Accounting Policies 62 Consolidated Income and Expenditure Account 64 Statement of Consolidated Historical Cost Surpluses and Deficits 65 Balance Sheets as at 31 July 20 11 66 Consolidated Cash Flow Statement 67 Reconciliation of Net Cash Flow to movement in Net Debt 68 Consolidated Statement of Total Recognised Gains and Losses 69 Notes to the Financial Statements 70 Chancellor’s Guild roll of honour 92 Chancellor’s Guild corporate donors and legacy pledges 93 Trusts, foundations and charities 94 Organisational chart 95 Lancaster University Report and Accounts 2011 3 ViCe-ChanCellor’s reView The growing reputation of Lancaster was marked this year by top ten placings in each of the UK’s major university been strengthened with a formal respond to this feedback to make sure The Government’s White Paper “Students collaboration with the Chinese Academy every department is outstanding.