Through the Ages II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baltic Country Holidays

SELF-DRIVE TOUR Along nature trails in Latvia and Estonia (Rīga – Pärnu – Saaremaa – Hiiumaa – Haapsalu – Tallinn, ~1270 km) Map 1 / Tour overview SAMPL E 1st day ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Arrival in Rīga, pick up the rented car at the airport. Drive from the airport in the direction of Riga city centre. Name of the hotel: ……… Address of the hotel: ……… Fr ee time in Rīga We recommend to visit the Old Town with the Dome cathedral (13th – 18th century) with its huge organ (to be the world’s fourth largest); Museum of history of Riga and navigation; the Riga castle built for the German nights now home to Latvia’s president and hosting Museum of foreign arts; the 3 brothers houses – the oldest in Riga, the St. Saviour’s church built in 1857 by a small group of British traders on 30 feet of British soil brought over as ballast in the ships transporting building materials; the 13th century Jēkaba church – the seat of Riga’s Roman Catholic archibishop; Latvia’s parliament; the Swedish gate; the round peaked 14th century Pulvertornis (powder tower) where there is a War museum; the red brick Gothic St. Peters church - its 72m spire has been built three times in the same baroque form, originally in 1660, again in 18th century after being hit by lightning and most recent after the destruction during WWII, now there is a lift to the second gallery of the spire for a marvellous panoramic view of Old Riga; the Occupation museum - an impressive account of the Soviet and Nazi occupations of Latvia between 1940 and 1944; the reconstructed Blackhead’s house – an architectural gem built in 1344 for the Blackhead’s guild of „Lauku celotajs” / „L Celotajs” Kugu iela 11, Riga LV-1048, Latvia, T: +(371) 7617600, Fax: +(371) 7830041, [email protected], www.celotajs.lv unmarried merchants, it was damaged in 1941 and rebuilt in 2000, the Great and the Small guildhalls. -

Apskates Objekti Muzeji Skatu Laukumi Iepirkšanās

24 ANNAS IELA GRODŅAS IELA BRĪVĪBAS IELA SPORTA IELA DAGMĀRAS IELA VIĻŅAS IELA 3 11 PALĪDZĪBAS IELA VIESTURA DĀRZS ARISTIDA BRIĀNA IELA 16 HANZAS IELA 3 TALLINAS IELA HANZAS IELA ŠARLOTES IELA 1 BUĻĻU IELA VIĻŅAS IELA HANZAS IELA 19 EMBŪTES IELA ANDREJSALA VALKAS IELA VAŠINGTONA ZAUBES IELA LAUKUMS 24 VESETAS IELA 5 LENČU IELA MAIZNĪCAS IELA RŪPNIECĪBAS IELA VERU IELA MATROŽU IELA DZEGUŽKALNS VIDUS IELA GANU IELA HANZAS IELA SALDUS IELA LOČU IELA 16 BUĻĻU IELA SAKARU IELA MEDNIEKU IELA 3 STRĒLNIEKU IELA 1 MIERA IELA DAUGAVGRĪVAS IELA EMIĻA MELNGAIĻA IELA STABU IELA BRUŅINIEKU IELA DZEGUŽU IELA DZIRNAVU IELA KR. BARONA IELA APSKATES OBJEKTI 36 Kristus Piedzimšanas 31 Rīgas Jūgendstila muzejs SKOLAS IELA SIGHTSEEING pareizticīgo katedrāle Art Nouveau Museum 1 TĒRBATAS IELA TALLINAS IELA ДОСТОПРИМЕЧАТЕЛЬНОСТИ Nativity of Christ Cathedral Рижский музей югендстиля IELA AUSEKĻA 11 Кафедральный собор Jugendstilmuseum Riga VĪLANDES IELA SEHENSWÜRDIGKEITEN 31 ĢERTRŪDES IELA CENTRS ĢIPŠA IELA Рождества Христова ELIZABETES IELA RŪPNIECĪBAS IELA 32 33 P. Stradiņa Medicīnas vēstures EKSPORTA IELA ALBERTA IELA CENTER 1 Rīgas pils Christi-Geburt-Kathedrale muzejs PULKVEŽA BRIEŽA IELA Riga Castle ЦЕНТР Vecā Sv. Ģertrūdes baznīca P. Stradins Museum of the STRĒLNIEKU IELA Рижский замок 38 Old St. Gertrude’s Church History of Medicine ANTONIJAS IELA ZAĻĀ IELA ZENTRUM Rigaer Schloss A.ČAKA IELA Старая Гертрудинская Музей истории медицины RĪGABAZNĪCAS IELA ELIZABETES IELA 2 Lielais Kristaps церковь им. П. Страдыня 39 Great Kristaps ENKURU IELA Alte St. Gertrude-Kirche -

Riga Municipality Annual Report 2018

Riga, 2019 CONTENT Report of Riga City Council Chairman .................................................................................................................... 4 Report of Riga City Council Finance Department Director ................................................................................... 5 Riga Municipality state ............................................................................................................................................. 6 Riga City population.............................................................................................................................................. 6 Riga Municipality economic state.......................................................................................................................... 7 Riga Municipality administration structure, functions, personnel........................................................................... 9 Riga Municipality property state .............................................................................................................................. 11 Value of Riga Municipal equity capital and its anticipated changes...................................................................... 11 Riga Municipality real estate property state........................................................................................................... 11 Execution of territory development plan ............................................................................................................... -

Alevist Vallamajani from Borough to Community House

Eesti Vabaõhumuuseumi Toimetised 2 Alevist vallamajani Artikleid maaehitistest ja -kultuurist From borough to community house Articles on rural architecture and culture Tallinn 2010 Raamatu väljaandmist on toetanud Eesti Kultuurkapital. Toimetanud/ Edited by: Heiki Pärdi, Elo Lutsepp, Maris Jõks Tõlge inglise keelde/ English translation: Tiina Mällo Kujundus ja makett/ Graphic design: Irina Tammis Trükitud/ Printed by: AS Aktaprint ISBN 978-9985-9819-3-1 ISSN-L 1736-8979 ISSN 1736-8979 Sisukord / Contents Eessõna 7 Foreword 9 Hanno Talving Hanno Talving Ülevaade Eesti vallamajadest 11 Survey of Estonian community houses 45 Heiki Pärdi Heiki Pärdi Maa ja linna vahepeal I 51 Between country and town I 80 Marju Kõivupuu Marju Kõivupuu Omad ja võõrad koduaias 83 Indigenous and alien in home garden 113 Elvi Nassar Elvi Nassar Setu küla kontrolljoone taga – Lõkova Lykova – Setu village behind the 115 control line 149 Elo Lutsepp Elo Lutsepp Asustuse kujunemine ja Evolution of settlement and persisting ehitustraditsioonide püsimine building traditions in Peipsiääre Peipsiääre vallas. Varnja küla 153 commune. Varnja village 179 Kadi Karine Kadi Karine Miljööväärtuslike Virumaa Milieu-valuable costal villages of rannakülade Eisma ja Andi väärtuste Virumaa – Eisma and Andi: definition määratlemine ja kaitse 183 of values and protection 194 Joosep Metslang Joosep Metslang Palkarhitektuuri taastamisest 2008. Methods for the preservation of log aasta uuringute põhjal 197 architecture based on the studies of 2008 222 7 Eessõna Eesti Vabaõhumuuseumi toimetiste teine köide sisaldab 2008. aasta teaduspäeva ettekannete põhjal kirjutatud üpris eriilmelisi kirjutisi. Omavahel ühendab neid ainult kaks põhiteemat: • maaehitised ja maakultuur. Hanno Talvingu artikkel annab rohkele arhiivimaterjalile ja välitööaine- sele toetuva esmase ülevaate meie valdade ja vallamajade kujunemisest alates 1860. -

Estonian Academy of Sciences Yearbook 2014 XX

Facta non solum verba ESTONIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES YEAR BOOK ANNALES ACADEMIAE SCIENTIARUM ESTONICAE XX (47) 2014 TALLINN 2015 ESTONIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES The Year Book was compiled by: Margus Lopp (editor-in-chief) Galina Varlamova Ülle Rebo, Ants Pihlak (translators) ISSN 1406-1503 © EESTI TEADUSTE AKADEEMIA CONTENTS Foreword . 5 Chronicle . 7 Membership of the Academy . 13 General Assembly, Board, Divisions, Councils, Committees . 17 Academy Events . 42 Popularisation of Science . 48 Academy Medals, Awards . 53 Publications of the Academy . 57 International Scientific Relations . 58 National Awards to Members of the Academy . 63 Anniversaries . 65 Members of the Academy . 94 Estonian Academy Publishers . 107 Under and Tuglas Literature Centre of the Estonian Academy of Sciences . 111 Institute for Advanced Study at the Estonian Academy of Sciences . 120 Financial Activities . 122 Associated Institutions . 123 Associated Organisations . 153 In memoriam . 200 Appendix 1 Estonian Contact Points for International Science Organisations . 202 Appendix 2 Cooperation Agreements with Partner Organisations . 205 Directory . 206 3 FOREWORD The Estonian science and the Academy of Sciences have experienced hard times and bearable times. During about the quarter of the century that has elapsed after regaining independence, our scientific landscape has changed radically. The lion’s share of research work is integrated with providing university education. The targets for the following seven years were defined at the very start of the year, in the document adopted by Riigikogu (Parliament) on January 22, 2014 and entitled “Estonian research and development and innovation strategy 2014- 2020. Knowledge-based Estonia”. It starts with the acknowledgement familiar to all of us that the number and complexity of challenges faced by the society is ever increasing. -

Events in Riga JANUARY | FEBRUARY | MARCH 2018 ������ER ��E ���� ���� R��� ����� EVENTS in RIGA JANUARY / FEBRUARY / MARCH 2018

Events in Riga JANUARY | FEBRUARY | MARCH 2018 DISCOER E R ASS! EVENTS IN RIGA JANUARY / FEBRUARY / MARCH 2018 CONTENTS 2 January Events 19 February Events 30 March Events 40 List of venue addresses RIGA TOURIST INFORMATION CENTRES At the Riga Tourist Information Centre (Rātslaukums 6), you can receive more information, as well as tickets to most of the events mentioned. Kaļķu iela 16. Phone: +371 67227444 Riga International Coach Terminal Prāgas iela 1. Phone: +371 67220555 Rātslaukums 6. Phone: +371 67037900 The Riga Tourism Information Center (Rātslaukums 6) will be closed from January 15, 2018 to February 18, 2018 for renovation works. Working hours: 10:00—18:00 [email protected] www.LiveRiga.com This information has been prepared on 30.11.2017. The Riga Tourism Development Bureau is not responsible for any changes made by event organisers. On national holidays (01.01., 30.03.2018.), certain locations may be closed or have shortened working hours. EVENT CALENDAR Date Time Event Venue Pg. 01.-07.01. 10:00-20:00 Christmas Fair on Līvu Square Līvu Square 6 01.-07.01. 10:00-20:00 Old Town Christmas Fair Dome Square 6 01.01.-31.03. 10:00-16:00 Winter at Riga Zoo Riga Zoo 6 01.01. 12:00-17:00 Hullabaloo/Jampadracis Latvian style Dzintari Forest Park 6 Latvian Ethnographic 01.-14.01. 15:00-20:00 Light reflections in the winter twilight 7 Open-air Museum 01.-28.01. 16:00-19:00 Winter Nights at Riga Zoo Riga Zoo 7 01.-14.01. The way through the Christmas Trees 2017 Riga 7 01.01. -

Overview of the Use and Preservation of State Assets in 2006

Overview of the Use and Preservation of State Assets in 2006 Auditor General’s summary of observations made during the year NAO’s report to the Parliament, Tallinn, 2007 Overview of the Use and Preservation of State Assets in 2006 Overview of the Use and Preservation of State Assets in 2006 Auditor General’s summary of observations made during the year Foreword by the Auditor General This overview summarises a part of the work of the National Audit Office (“NAO”) in auditing the state assets in 2006 and 2007. The overview presents a selection of problems associated with state assets and their management, which in the opinion of the NAO require special attention of the Parliament and the public. Specific information on the implementation of the 2006 budget, government accounting procedures and reporting can be obtained from the consolidated annual report of the state and the evaluation of this report by the NAO. The examples provided in the Overview are presented to illustrate the problems. The report of the NAO includes only a small part of the observations made during the audits and the ministries should not use this as a comparison base in managing state assets. The audit reports underlying this overview are available in full on our web site www.riigikontroll.ee. The aim of the NAO is to help the state to be a good manager. The independent information provided by the NAO helps the Parliament to enhance the efficiency of the parliamentary control. The need for parliamentary control has been also emphasised by the Parliament through the formation of a separate committee for cooperation with the NAO and the Government of the Republic. -

Events in Riga April / May / June 2015 Planeta 210X100mm PRINT.Pdf 1 09.12.2014 10:09:28 EVENTS in RIGA APRIL / MAY / JUNE 2015

Events in Riga April / May / June 2015 planeta 210x100mm _ PRINT.pdf 1 09.12.2014 10:09:28 EVENTS IN RIGA APRIL / MAY / JUNE 2015 CONTENTS 2 April Events 21 May Events 37 June Events 48 List of venue addresses RIGA TOURIST INFORMATION CENTRES At the Riga Tourist Information Centre (Rātslaukums 6), you can receive more information, as well as tickets to most of the events mentioned. Rātslaukums 6. Phone: +371 67037900 Kaļķu iela 16. Phone: +371 67227444 Riga International Coach Terminal Prāgas iela 1. Phone: +371 67220555 Working hours: April: 10:00–18:00 May, June : 9:00–19:00 [email protected] www.LiveRiga.com in cooperation with: This information has been prepared on 25.02.2015. The Riga Tourism Development Bureau is not responsible for any changes made by event organisers. On national holidays (03.-06.04., 01.-04.05., 22.-24.06.2015), certain locations may be closed or have shortened working hours. EVENT CALENDAR Date Time Event Venue Pg. 01.04.- 9:00-19:00 Egle's Crafts Fair Egle's Crafts Fair 8 31.12. 10:00- Two Centuries of Italian Art Museum Riga 01.-19.04. 18:00 Portrait Painting. 1580-1780: 8 Bourse (II-VII) An Exhibition 10:00- Jewellery artist Emmanuel 18:00 (I-V), 01.-11.04. Lacoste`s exhibition: "The Art gallery Putti 8 11:00-17:00 Seven Deadly Sins" (VI) 10:00- 04.03.- Exhibition "Gem of Art Riga Art Nouveau 18:00 8 24.05. Nouveau: Riga Synagogue" Museum (II-VII) The Pauls Stradins 01.04.- 11:00-17:00 Exhibition "Anatomist: The museum of 8 16.05. -

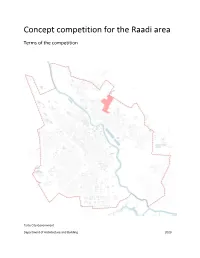

Concept Competition for the Raadi Area

Concept competition for the Raadi area Terms of the competition Tartu City Government Department of Architecture and Building 2020 Table of contents 1. Objective, competition area and contact area of the concept competition .......................................................... 3 2. History .................................................................................................................................................................... 5 3. Detailed plans and architectural plans in effect for the area ................................................................................. 7 4. Streets of the competition area ........................................................................................................................... 11 5. Environment and landscaping .............................................................................................................................. 12 6. Competition task by properties ........................................................................................................................... 13 7. Organisation of the competition .......................................................................................................................... 17 7.1 Organiser of the competition ........................................................................................................................ 17 7.2 Competition format ...................................................................................................................................... -

0Db570ad569a08f8f6772559dcb

ПРАВИТЕЛЬСТВО МОСКВЫ ДЕПАРТАМЕНТ КУЛЬТУРЫ ГОРОДА МОСКВЫ GOVERNMENT OF MOSCOW MOSCOW DEPARTMENT OF CULTURE ЕВРОАЗИАТСКАЯ РЕГИОНАЛЬНАЯ АССОЦИАЦИЯ ЗООПАРКОВ И АКВАРИУМОВ EURASIAN REGIONAL ASSOCIATION OF ZOOS & AQUARIUMS МОСКОВСКИЙ ГОСУДАРСТВЕННЫЙ ЗООЛОГИЧЕСКИЙ ПАРК MOSCOW ZOO ИНФОРМАЦИОННЫЙ СБОРНИК ЕВРОАЗИАТСКОЙ РЕГИОНАЛЬНОЙ АССОЦИАЦИИ ЗООПАРКОВ И АКВАРИУМОВ INFORMATIONAL ISSUE OF EURASIAN REGIONAL ASSOCIATION OF ZOOS AND AQUARIUMS ISSUE 33 VLUME II МОСКВА 2014 2 OVERNMENT OF MOSCOW COMMITTEE FOR CULTURE EURASIAN REGIONAL ASSOCIATION OF ZOOS & AQUARIUMS MOSCOW ZOO INFORMATIONAL ISSUE OF EURASIAN REGIONAL ASSOCIATION OF ZOOS AND AQUARIUMS ISSUE № 33 VOLUME II ________________ MOSCOW – 2014 – 3 The current issue comprises information on EARAZA member zoos and other zoological institutions. The first part of the publication includes collection inventories and data on breeding in all zoological collections. The second part of the issue contains information on the meetings, workshops, trips and conferences which were held both in our country and abroad, as well as reports on the EARAZA activities. Chief executive editor Vladimir Spitsin President of Moscow Zoo Compiling Editors: Т. Andreeva V. Frolov N. Karpov L. Kuzmina V. Ostapenko V. Sheveleva T. Vershinina Translators: A. Simonova © 2014 Moscow Zoo 4 Eurasian Regional Association of Zoos and Aquariums (EARAZA) 123242 Russia, Moscow, Bolshaya Gruzinskaya 1. Telephone/fax: (499) 255-63-64 E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Web: www.earaza.ru EARAZA Chairman: Vladimir V. Spitsin President of Moscow Zoo, Correspondent Member of the Russian Academy of Natural Sciences Members of the presidium: Vladimir V. Fainstein Deputy Director for Zoovet of Tallinn Zoo Alexander P. Barannikov Director of Rostov Zoo Aleksei P. Khanzazuk Director of Kishinev Zoo Premysl Rabas Director Zoo Dvur Kralove nad Labem Vladimir N. -

Impeeriumi Viimane Autovõistlus

THE LAST MOTOR RACE OF THE EMPIRE The Third Baltic Automobile and Aero Club Competition for the Grand Duchess Victoria Feodorovna Prize Tallinn 2014 Text and design: Rene Levoll ISBN 978-9949-38-060-2 Copyright © 2014 Rene Levoll Estonian Old Technics Museum Foundation CONTENTS CONTENTS .......................................................................... 3 FOREWORD ......................................................................... 5 The Baltic Automobile and Aero Club ................................... 7 Rules of the race ...................................................................... 11 Day 1: 11/24 July ................................................................... 13 The evening of the previous day, July 10/23 ................................. 26 The Morning of the first day of the Victoria Race 27 ..................... 27 Day 2: 12/25 July 28 .............................................................. 28 On the same day ...................................................................... 33 Day 3: 13/26 July ................................................................... 34 On the same day ...................................................................... 41 Day 4: 14/27 July ................................................................... 41 On the same day ...................................................................... 49 Day 5: 15/28 July ................................................................... 50 On the same day ..................................................................... -

Download Download

12 ERMi aastaraamat 52, lk 12–29 Matthias Johann Eisen kui Eesti Rahva Muuseumi juhatuse esimees Piret Õunapuu Matthias Johann Eisen on olnud üks omanäolisemaid ja markantsemaid tegelasi meie kultuuriloos. Oma pika elu (1857–1934) jooksul jõudis ta tegeleda paljude as- jadega, kirjutada hulga raamatuid ja olla aktiivne avaliku elu tegelane ning suure- pärane kõnemees. 18. mail 1926 valiti M. J. Eisen Eesti Rahva Muuseumi direktori Ilmari Mannineni ettepanekul ühel häälel muuseumi auliikmeks tema teenete eest rahvateaduse alal. Seni on käsitletud Eiseni ja Eesti Rahva Muuseumi vahekorda vähe ja vigadega. Kõige põhjalikum on Helmi Kurriku suhteliselt lühike artikkel 1938. aastal ilmu- nud raamatus M. J. Eiseni elu ja töö. Põgusalt käsitleb ERMi osa Eiseni elus ka Karl Eduard Sööt oma artiklis „M. J. Eiseni elust ja tegevusest“ Eiseni 70. sünnipäeva juubelialbumis (1927). Alljärgnevalt püüan anda ülevaate Eiseni tegevusest seoses Eesti Rahva Muu- seumi ja sealsete inimestega, kasutades eelkõige arhiivimaterjale ja Eesti Kirjandus- muuseumis hoitavaid Eiseni päevikuid. Käsitlen teda pigem inimesena ja ametni- kuna, ERMi juhatuse esimehena, mitte aga teadlasena seotuna üksikute ERMi all- üksustega. Algusaastad M. J. Eisen on olnud seotud Eesti Rahva Muuseumiga selle asutamisplaanidest saa- dik. Eesti muuseumi asutamise otseseks ajendiks oli dr Jakob Hurda surm 1906. aasta viimasel päeval. See oli tõeline ehmatus eesti rahvale ja kurb sündmus suutis koondada tolle aja ärksamad mehed ühise idee nimel. Hurda matusepäeval, 4. jaa- nuaril (17. jaanuar ukj) kell 7 õhtul kogunes Vanemuise väiksesse saali Eesti vai- mueliit. Koosolekut juhtinud Jaan Tõnissoni sõnul tekkinud tal matuserongis mõte „Dr. Hurti mälestust… jäädawamalt auustada“ ja seetõttu kutsus ta kokku need, keda õnnestus kätte saada.