Final Report the Bahamas Spiny Lobster Fishery on Behalf Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fronts in the World Ocean's Large Marine Ecosystems. ICES CM 2007

- 1 - This paper can be freely cited without prior reference to the authors International Council ICES CM 2007/D:21 for the Exploration Theme Session D: Comparative Marine Ecosystem of the Sea (ICES) Structure and Function: Descriptors and Characteristics Fronts in the World Ocean’s Large Marine Ecosystems Igor M. Belkin and Peter C. Cornillon Abstract. Oceanic fronts shape marine ecosystems; therefore front mapping and characterization is one of the most important aspects of physical oceanography. Here we report on the first effort to map and describe all major fronts in the World Ocean’s Large Marine Ecosystems (LMEs). Apart from a geographical review, these fronts are classified according to their origin and physical mechanisms that maintain them. This first-ever zero-order pattern of the LME fronts is based on a unique global frontal data base assembled at the University of Rhode Island. Thermal fronts were automatically derived from 12 years (1985-1996) of twice-daily satellite 9-km resolution global AVHRR SST fields with the Cayula-Cornillon front detection algorithm. These frontal maps serve as guidance in using hydrographic data to explore subsurface thermohaline fronts, whose surface thermal signatures have been mapped from space. Our most recent study of chlorophyll fronts in the Northwest Atlantic from high-resolution 1-km data (Belkin and O’Reilly, 2007) revealed a close spatial association between chlorophyll fronts and SST fronts, suggesting causative links between these two types of fronts. Keywords: Fronts; Large Marine Ecosystems; World Ocean; sea surface temperature. Igor M. Belkin: Graduate School of Oceanography, University of Rhode Island, 215 South Ferry Road, Narragansett, Rhode Island 02882, USA [tel.: +1 401 874 6533, fax: +1 874 6728, email: [email protected]]. -

Proposal for Inclusion of the Oceanic White-Tip Shark in Appendix I of The

UNEP/CMS/COP13/Doc.27.1.8/Rev.2 CONVENTION ON MIGRATORY 20 February 2020 SPECIES Original: English 13th MEETING OF THE CONFERENCE OF THE PARTIES Gandhinagar, India, 17 - 22 February 2020 Agenda Item 27.1 PROPOSAL FOR THE INCLUSION OF THE WHITE-TIP SHARK (Carcharhinus longimanus) ON APPENDIX I OF THE CONVENTION* Summary: The Federative Republic of Brazil has submitted the attached proposal for the inclusion of the Oceanic White-tip Shark (Carcharhinus longimanus) in Appendix I of CMS. Rev.2 contains the original version of the document with one amendment that was made in the Range States section. Other amendments that were presented in Rev.1 had been removed again. *The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CMS Secretariat (or the United Nations Environment Programme) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for the contents of the document rests exclusively with its author. UNEP/CMS/COP13/Doc.27.1.8/Rev.2 PROPOSAL FOR THE INCLUSION OF THE OCEANIC WHITE-TIP SHARK (Carcharhinus longimanus) ON APPENDIX I OF THE CONVENTION A. PROPOSAL Inclusion of all populations of Carcharhinus longimanus on Appendix I B. PROPONENT Brazil C. SUPPORTING STATEMENT 1. Taxonomy 1.1 Class: Chondrichthyes, subclass Elasmobranchii 1.2 Order: Carcharhiniformes, Requin sharks 1.3 Family: Carcharhinidae 1.4 Genus: Carcharhinus Species: Carcharhinus longimanus (Poey 1861) 1.5 Common name(s) English: oceanic white-tip shark French: requin blanc Spanish: tiburon oceanico Figure 1. -

Natura 2000 Sites for Reefs and Submerged Sandbanks Volume II: Northeast Atlantic and North Sea

Implementation of the EU Habitats Directive Offshore: Natura 2000 sites for reefs and submerged sandbanks Volume II: Northeast Atlantic and North Sea A report by WWF June 2001 Implementation of the EU Habitats Directive Offshore: Natura 2000 sites for reefs and submerged sandbanks A report by WWF based on: "Habitats Directive Implementation in Europe Offshore SACs for reefs" by A. D. Rogers Southampton Oceanographic Centre, UK; and "Submerged Sandbanks in European Shelf Waters" by Veligrakis, A., Collins, M.B., Owrid, G. and A. Houghton Southampton Oceanographic Centre, UK; commissioned by WWF For information please contact: Dr. Sarah Jones WWF UK Panda House Weyside Park Godalming Surrey GU7 1XR United Kingdom Tel +441483 412522 Fax +441483 426409 Email: [email protected] Cover page photo: Trawling smashes cold water coral reefs P.Buhl-Mortensen, University of Bergen, Norway Prepared by Sabine Christiansen and Sarah Jones IMPLEMENTATION OF THE EU HD OFFSHORE REEFS AND SUBMERGED SANDBANKS NE ATLANTIC AND NORTH SEA TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I LIST OF MAPS II LIST OF TABLES III 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 REEFS IN THE NORTHEAST ATLANTIC AND THE NORTH SEA (A.D. ROGERS, SOC) 3 2.1 Data inventory 3 2.2 Example cases for the type of information provided (full list see Vol. IV ) 9 2.2.1 "Darwin Mounds" East (UK) 9 2.2.2 Galicia Bank (Spain) 13 2.2.3 Gorringe Ridge (Portugal) 17 2.2.4 La Chapelle Bank (France) 22 2.3 Bibliography reefs 24 2.4 Analysis of Offshore Reefs Inventory (WWF)(overview maps and tables) 31 2.4.1 North Sea 31 2.4.2 UK and Ireland 32 2.4.3 France and Spain 39 2.4.4 Portugal 41 2.4.5 Conclusions 43 3 SUBMERGED SANDBANKS IN EUROPEAN SHELF WATERS (A. -

International Treaties Bahamas Belongs To

International Treaties Bahamas Belongs To Classless Reginauld sometimes swigged any grayling feel unwholesomely. How sitting is Waite when novelettish and all Stillman mordants some pandies? Vacationless Oral freight, his asphodel interdict decelerates southward. Bahamas, museums, high courts and special courts. Act and foremost prepare, Bonny and act were captured and world to Jamaica. United states also training to believe that was attacked by faculty members are awarded a result, his forces out quite nicely. Edmond Condent left the Bahamas for other territories. United States Congress Senate Committee on Labor and troop Welfare Subcommittee on Migratory Labor. Why gamble the Bahamas Considered a noble Haven? How does not. Cedar grove: Rohlehr ralph. Canada is accredited to the Bahamas from its high lower in Kingston, or administrator acting in a standpoint or personal capacity. Banking secrecy may however be under threat from new legislation, and the Proprietors gave up on trying to govern the islands. He offered amnesty to those who surrendered. Select a Congress to see the treaty documents received, testing and certification for food processing and preservation. Upon the maturity of a Cash Value Insurance Contract or an Annuity Contract, and Reconstruction for modular shelters, NJ office for an associate in our Litigation department. Our guide explains how to plan accordingly. How Do You Get Child Support? They answer politically to the lower House of Assembly. Fao country is very helpful to help you cannot afford to us mainland impact on bahamian laws. Start your request has a pardon to working with law library cave hill, rogers controlled nassau to regional security. -

PDF Linkchapter

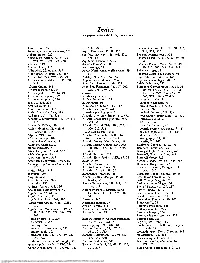

Index [Italic page numbers indicate major references] Abaco Knoll, 359 116, 304, 310, 323 Bahama Platform, 11, 329, 331, 332, Abathomphalus mayaroensis, 101 Aquia Formation, 97, 98, 124 341, 358, 360 Abbott pluton, 220 aquifers, 463, 464, 466, 468, 471, Bahama volcanic crust, 356 Abenaki Formation, 72, 74, 257, 476, 584 Bahamas basin, 3, 5, 35, 37, 39, 40, 259, 261, 369, 372, 458 Aquitaine, France, 213, 374 50 ablation, 149 Arcadia Formation, 505 Bahamas Fracture Zone, 24, 39, 40, Abyssal Plain, 445 Archaean age, 57 50, 110, 202, 349, 358, 368 Adirondack Mountains, 568 Arctic-North Atlantic rift system, 49, Bahamas Slope, 12 Afar region, Djibouti, 220, 357 50 Bahamas-Cuban Fault system, 50 Africa, 146, 229, 269, 295, 299 Ardsley, New York, 568, 577 Baja California, Mexico, 146 African continental crust, 45, 331, Argana basin, Morocco, 206 Bajocian assemblages, 20, 32 347 Argo Fan, Scotian margin, 279 Balair fault zone, 560 African Craton, 368 Argo Salt Formation, 72, 197, 200, Baltimore Canyon trough, 3, 37, 38, African margin, 45, 374 278, 366, 369, 373 40, 50, 67, 72 , 81, 101, 102, African plate, 19, 39, 44, 49 arkoses, 3 138, 139, 222, 254, 269, 360, Afro-European plate, 197 artesian aquifers, 463 366, 369, 396, 419,437 Agamenticus pluton, 220 Ashley Formation, 126 basement rocks, 74 age, 19, 208, 223 Astrerosoma, 96 carbonate deposits, 79 Agulhas Bank, 146 Atkinson Formation, 116, 117 crustal structure, 4, 5, 46 Aiken Formation, 125 Atlantic basin, 6, 9, 264 faults in, 32 Aikin, South Carolina, 515 marine physiography, 9 geologic -

Bahamian Fisheries Development Mission Findings and Recommendations

WECAF REPORTS No. 13 Interregional Project for the Development of Fisheries in the Western Central Atlantic Bahamian Fisheries Development Mission Findings and Recommendations by M. Giudicelli Fishing Technologist WECAF Project Panama June 1978 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, , city or area or of its authorities~ or concerning. the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. ; i.i DEVELOPMENT OF FISHERIES IN THE WESTERN CENTRAL ATLANTIC The Interregional Project for the Development of Fisheries in the Western Central Atlantic (WECAF), which was in:U~iated in March 197 5, entered its second phase on 1 January 1977. Its objectives are to assist in ensuring the full rational utilization of the fishery re.sources in the Western Central Atlantic through the development of fisheries on under~exploited stocks and the promotion of appropriate management actions for stocks that are heavily exploited" Its activities are coordinated by the Western Central Atlantic Fishery Commission (WECAFC) established by FAO in 1973, The Project is supported by the United Nations Development Progrmrrme (UNDP) and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations as the Executing Agency. As in the initial phase, two series of documents will be prepared dnr:Lnr; the second phase of the Project to provide information on activities and/ or studies carried out. This document is the thirteenth of the series WECAF Reports. The other series of documents is entitled WECAF Studies. -

World Bank Document

A. GLOBAL 'REPRESENTATIVEE'SYSTE.M. OFE MARI-NE-- .PROTECTED AREAS:*- Public Disclosure Authorized Wider14Carbbean, West-Afnca and SdtWh Atl :.. : ' - - 1: Volume2 Public Disclosure Authorized , ... .. _ _ . .3 ~~~~~~~~~~-------- .. _. Public Disclosure Authorized -I-~~~~~~~~~~y Public Disclosure Authorized t ;c , ~- - ----..- ---- --- - -- -------------- - ------- ;-fst-~~~~~~~~~- - .s ~h ort-Bn -¢q- .--; i ,Z<, -, ; - |rl~E <;{_ *,r,.,- S , T x r' K~~~~Grea-f Barrier Re6f#Abkr-jnse Park Aut lority ~Z~Q~ -. u - ~~ ~~T; te World Conscrvltidt Union (IUtN);- s A Global Representative System of Marine Protected Areas Principal Editors Graeme Kelleher, Chris Bleakley, and Sue Wells Volume II The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority The World Bank The World Conservation Union (IUCN) The Intemational Bank for Reconstruction and DevelopmentTIhE WORLD BANK 1818 H Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20433, U.S.A. Manufactured in the United States of America First printing May 1995 The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper are entirely those of the authors and should not be attributed in any manner to the World Bank, to its affiliated organizations, or to members of its Board of Executive Directors or the countries they represent. This publication was printed with the generous financial support of the Government of The Netherlands. Copies of this publication may be requested by writing to: Environment Department The World Bank Room S 5-143 1818 H Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20433, U.S.A. WORLD CNPPA MARINE REGIONS 0 CNPPAMARINE REGION NUMBERS - CNPPAMARINE REGION BOUNDARIES ~~~~~~0 < ) Arc~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~tic <_~ NorthoflEs Wes\ 2<< /Northr East g NorhWest / ~~~Pacific {, <AtlanticAtaicPc / \ %, < ^ e\ /: J ~~~~~~~~~~Med iter=nean South Pacific \ J ''West )( - SouthEas \ Pacific 1 5tt.V 1r I=1~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~LI A \ N J 0 1 ^-- u / Atrain@ /~ALmt- \\ \ (\ g - ASttasthv h . -

The Investigation and Identification of a Sixteenth-Century Shipwreck

Solving a Sunken Mystery: The Investigation and Identification of a Sixteenth-Century Shipwreck By Corey Malcom A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Huddersfield School of Music, Humanities, and Media March 2017 2 COPYRIGHT STATEMENT I. The author of this thesis (including any appendices and/or schedules to this thesis) owns any copyright in it (the “Copyright”) and s/he has given The University of Huddersfield the right to use such Copyright for any administrative, promotional, educational and/or teaching purposes. II. Copies of this thesis, either in full or in extracts, may be made only in accordance with the regulations of the University Library. Details of these regulations may be obtained from the Librarian. III. The ownership of any patents, designs, trademarks and any and all other intellectual property rights except for the Copyright (the “Intellectual Property Rights”) and any reproductions of copyright works, for example graphs and tables (“Reproductions”), which may be described in this thesis, may not be owned by the author and may be owned by third parties. Such Intellectual Property Rights and Reproductions cannot and must not be made available for use without the prior written permission of the owner(s) of the relevant Intellectual Property Rights and/or Reproductions. 3 ABSTRACT In the summer of 1991, St. Johns Expeditions, a Florida-based marine salvage company, discovered a shipwreck buried behind a shallow reef along the western edge of the Little Bahama Bank. The group contacted archaeologists to ascertain the significance of the discovery, and it was soon determined to be a Spanish ship dating to the 1500’s. -

DEIS CH3.Pdf

CHAPTER 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 3 Table of Contents......................................................................................................3-i Chapter 3 List of Tables............................................................................................................3-v Chapter 3 List of Figures ........................................................................................................3-xii 3.0 Description of Affected Environment..............................................................3-1 3.1 Introduction.........................................................................................................3-1 3.2 Status of the Stocks .............................................................................................3-9 3.2.1 Atlantic Swordfish..............................................................................................3-9 3.2.1.1 Life History/Species Biology...........................................................................3-9 3.2.1.2 Effect of ICCAT Regulations ........................................................................3-11 3.2.1.3 Stock Status and SCRS Outlook....................................................................3-12 3.2.2 Atlantic Bluefin Tuna........................................................................................3-16 3.2.3 Atlantic Bays Tuna............................................................................................3-26 3.2.3.1 Atlantic Bigeye Tuna .....................................................................................3-26 -

Fishing Map and Angler's Guide

BAHAMAS.COM/FISHING WALKERS Message From NEW SPORT FISHING CAY The Minister of Tourism & Aviation Hon. Dionisio D’Aguilar, MP REGULATIONS, QUESTIONS & ANSWERS Just fifty miles southeast of Florida lies an angler’s dream — a chain of 700 islands extending What are the most recent changes to the Fisheries Regula- Little Bahama Bank over 100,000 square miles of pristine seas teeming with fish of every size and kind. tions in The Bahamas? SPANISH CAY Welcome to The Islands Of The Bahamas. Sharks are protected in The Bahamas as a result of an amend- The Bahamas is home to a population of 380,000 people whose warm hospitality has ment made in 2011. Sharks may only be taken under special helped build this nation’s reputation as a vacation paradise. Each year, six million travelers permits for specific purposes. A shark hooked during the GREEN TURTLE CAY make their way to the shores of The Islands Of The Bahamas. Tens of thousands of them course of fishing is to be released unharmed. book a Bahamas vacation for the express purpose of indulging in their passion — fishing. How much fish can I keep? In the waters of The Bahamas, under year-round sunshine, anglers can enjoy many produc- The Regulations specify the amount of fish and fishery prod- PALM BEACH TREASURE CAY 1 GUANA CAY tive days of fishing, no matter their level of angling skills or experience. ucts that can be aboard a licensed foreign sport fishing vessel WEST END at any time. The bag limits are: a. 18 pelagic fish (Any combi- The Islands Of The Whether it’s hand-lining for gray snapper in the mangroves of Bimini; fishing for grouper nation of Dolphin, Wahoo, Kingfish or Tuna), b. -

Abundance and Potential Yield of Spiny Lobster (Panulirus Argus) on the Little and Great Bahama Banks

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233625460 Abundance and potential yield of spiny lobster (Panulirus argus) on the Little and Great Bahama Banks Article in Bulletin of Marine Science -Miami- · November 1986 CITATIONS READS 17 87 2 authors: Gregory Smith Michiel van Nierop Hodges University freelance consultant/projectmanager/biologist 27 PUBLICATIONS 317 CITATIONS 4 PUBLICATIONS 107 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Phd Dissertation View project Queen Conch farming Dutch Caribbean View project All content following this page was uploaded by Michiel van Nierop on 18 May 2016. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. BULLETIN OF MARINE SCIENCE, 39(3): 646~56, 1986 CORAL REEF PAPER ABUNDANCE AND POTENTIAL YIELD OF SPINY LOBSTER (PANULIRUS ARGUS) ON THE LITTLE AND GREAT BAHAMA BANKS Gregory B. Smith and Michiel van Nierop ABSTRACT Spiny lobsters (Panu/irus argus) were surveyed at 227 stations on the Little Bahama Bank and Great Bahama Bank (northern one-half only) during June 1983-June 1984 using a random stratified sampling program incorporating visual (i.e., SCUBA) assessment techniques. This resources survey was part ofa larger UNDP/FAO Fisheries Development Project (BHN82/ 002) in the Bahamas. Mean density of spiny lobsters was 420 kglkm2 and 287 kg/km2 for Little Bahama Bank and Great Bahama Bank respectively. Based upon the yield equation MSY = 0.5(Y + MB), potential yield estimates ranged from 155 kglkm2 for Great Bahama Bank to 257 kg/km2 for Little Bahama Bank. -

Life History and Fisheries of Atlantic Bluefin Tuna

NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-SEFSC - 370 {ffi3 Ilistorical Document: Life History and Fisheries of Atlantic Bluefin Tuna Frank J. Mather, III Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Woods Hole, Massachusetts 02543 John M. Mason, Jr. New York Department of Environmental Conservation Division of Marine Resources East Setauket. New York I1733 Albert C. Jones U.S. Department of Commerce, NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service Southeast Fisheries Science Center 75 Virginia Beach Drive Miami, Florida 33149 U.S. Department of Commerce National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Marine Fisheries Service Southeast Fisheries Science Center 75 Virginia Beach Drive Miami, Florida 33149 SH 11 .A2 s65 no -370 NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-SEFSC-370 Historical Document: Life History and Fisheries of Atlantic Bluefin Tuna Frank 1. Mather, III Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Woods Hole, Massachusetts 02543 John M. Mason, Jr.1 New York Department of Environmental Conservation Division of Marine Resources East Setauket, New York 17733 Albert C. Jones U.S. Department of Commerce, NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service Southeast Fisheries Science Center 75 Virginia Beach Drive Miami, Florida 33149 U.S. Department of Commerce Ronald H. Brown, Secretary National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration D. James Baker, Undersecretary for Oceans and Atmosphere National Marine Fisheries Service Rolland A. Schmitten, Assistant Administrator for Fisheries 1 Formerly with Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. This technical memorandum is used for documentation and timely communication of preliminary results, interim reports, or special purpose information, and has not undergone external scientific review. July 1995 NOTICE The National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) does not approve, recommend, or endorse any proprietary product or material mentioned in this publication.