A History of Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Country Profile Laos

Country profile Laos GEOGRAPHY Laos is located in southeast Asia and is approximately the same size as Victoria. It is one of the few landlocked countries in Asia with a landscape dominated by rivers and mountains. The Mekong River runs the entire length of the country and forms the national border with Thailand. The climate is tropical, with high temperature and humidity levels. The rainy season is from May to November. The tropical forests which cover much of the country are rapidly being logged. PEOPLE The official language is Lao, but French, English and other languages are also spoken. Theravada Buddhism is the dominant religion, although animist beliefs are also common, especially in the mountainous areas. The population of Laos consists of approximately 130 different ethnic groups and 80 percent of the population live in rural areas. HISTORY Laos has its origins in the ancient Lao kingdom of Lan Xang, established in the 14th century. For 300 years this kingdom Map courtesy of The General Libraries, included parts of modern-day Cambodia and Thailand, as well The University of Texas at Austin as all of what is now Laos. From the late 18th century, Laos came under the control of Siam (now Thailand) before coming under the control of France in the late 19th century. policy, but has struggled to find its position within a changing political and economic landscape. Despite tentative reforms, In 1975, communist forces ended the monarchy in Laos and Laos remains poor and dependent on international donations. ruled with a regime closely aligned to Vietnam and the Soviet It became a member of ASEAN in 1997. -

A New Method of Classification for Tai Textiles

A New Method of Classification for Tai Textiles Patricia Cheesman Textiles, as part of Southeast Asian traditional clothing and material culture, feature as ethnic identification markers in anthropological studies. Textile scholars struggle with the extremely complex variety of textiles of the Tai peoples and presume that each Tai ethnic group has its own unique dress and textile style. This method of classification assumes what Leach calls “an academic fiction … that in a normal ethnographic situation one ordinarily finds distinct tribes distributed about the map in an orderly fashion with clear-cut boundaries between them” (Leach 1964: 290). Instead, we find different ethnic Tai groups living in the same region wearing the same clothing and the same ethnic group in different regions wearing different clothing. For example: the textiles of the Tai Phuan peoples in Vientiane are different to those of the Tai Phuan in Xiang Khoang or Nam Nguem or Sukhothai. At the same time, the Lao and Tai Lue living in the same region in northern Vietnam weave and wear the same textiles. Some may try to explain the phenomena by calling it “stylistic influence”, but the reality is much more profound. The complete repertoire of a people’s style of dress can be exchanged for another and the common element is geography, not ethnicity. The subject of this paper is to bring to light forty years of in-depth research on Tai textiles and clothing in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic (Laos), Thailand and Vietnam to demonstrate that clothing and the historical transformation of practices of social production of textiles are best classified not by ethnicity, but by geographical provenance. -

Contemporary Phuthai Textiles

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2004 Contemporary Phuthai Textiles Linda S. McIntosh Simon Fraser University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons McIntosh, Linda S., "Contemporary Phuthai Textiles" (2004). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 481. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/481 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Contemporary Phuthai Textiles Linda S. McIntosh Simon Fraser University [email protected] © Linda S. McIntosh 2004 The hand-woven textiles of the Phuthai ethnic group continue to represent Phuthai identity but also reflect exposure to foreign elements such as through trade and changes in the regional political power. If one asks a Phuthai woman what is Phuthai dress, she will answer, sin mii lae suea lap lai, or a skirt decorated with weft ikat technique and a fitted blouse of indigo dyed cotton, decorated with hand-woven, patterned red silk. Despite the use of synthetic dyes readily available in the local markets, many women still grow indigo and cotton, and indigo-stained hands and the repetitious sounds of weaving are still found in Phuthai villages. This paper focuses on the Phuthai living in Savannakhet Province, Laos, but they are also found in Khammuan, Bolikhamsay, and Salavan provinces of Laos as well as in Thailand and Vietnam.1 Contemporary refers to textile production in the last thirty years but particularly in the last ten years after the liberalization of the Lao government policies and the return of private business and tourism after the 1980s. -

Iron Man of Laos Prince Phetsarath Ratanavongsa the Cornell University Southeast Asia Program

* fll!!I ''{f'':" ' J.,, .,.,Pc, IRON MAN OF LAOS PRINCE PHETSARATH RATANAVONGSA THE CORNELL UNIVERSITY SOUTHEAST ASIA PROGRAM The Southeast Asia Program was organized at Cornell University in the Department of Far Eastern Studies in 1950. It is a teaching and research program of interdisciplinary studies in the humanities, social sciences, and some natural sciences. It deals with Southeast Asia as a region, and with the individual countries of the area: Brunei, Burma, Indonesia, Kampuchea, Laos, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam. The activities of the Program are carried on both at Cornell and in Southeast Asia. They include an undergraduate and graduate curriculum at Cornell which provides instruction by specialists in Southeast Asian cultural history and present-day affairs and offers intensive training in each of the major languages of the area. The Program sponsors group research projects on Thailand, on Indonesia, on the Philippines, and on linguistic studies of the languages of the area. At the same time, individual staff and students of the Program have done field research in every Southeast Asian country. A list of publications relating to Southeast Asia which may be obtained on prepaid order directly from the Program is given at the end of this volume. Information on Program staff, fellowships, requirements for degrees, and current course offerings is obtainable· from the Director, Southeast Asia Program, 120 Uris Hall, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 14853. 11 IRON MAN OF LAOS PRINCE PHETSARATH RATANAVONGSA by "3349" Trc1nslated by .John B. �1urdoch F.di ted by · David K. \-vyatt Data Paper: Number 110 -Southeast Asia Program Department of Asian Studies Cornell University, Ithaca, New York .November 197·8 Price: $5.00 111 CORNELL UNIVERSITY SOUTHEAST ASIA PROGRAM 1978 International Standard Book Number 0-87727-110-0 iv C.ONTENTS FOREWORD • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • . -

ED 206 7,6 AUTHOR V Understanding Laotian People

DOCU5ANT RESUME ED 206 7,6 OD 021 678 AUTHOR V Harmon, Roger E. and Culture. TITLE Understanding Laotian People, Language, Bilingual Education ResourceSeries. INSTITUTION Washington Office of the StateSuperintendent of Public Instruction, Olympia. SPONS AGENCY Office of Education (DREW)Washington, D.C. PUB.DATE (79) NOTE 38p. ERRS PRICE MF11/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *adjustment (to Environment): AsianHistory: Bilingual Education; Comparative Education;*Cultural Influences: Elementary SecondaryEducation; English (Second Language): *Laotians: *Refugees;*Second Language Instruction ABSTRACT This is a guide for teachersand administrators to familiarize them with the Laotianpeople, language and culture. The first section contains a brief geographyand history of Laos, a discussion of the ethnic and lingustic grpupsof Laos, and information on the economic andreligious life of these groups. Section two describes the Laotianrefugee experience and considers life in the some of the adjustmentsLaotians must make for their new United States. This section alsoexplains elements of the international, national and local supportsystems which assist Indochinese refugees. Sectionthree gives a brief history ofthe educational system in Laos, andthe implications for educational Suggestions for needs of Laotians nowresiding in the United States. working with Laotianp in'the schoolsand some potential problem areas of the are ale) covered. Thelast section presents an analysis Laotian language. Emphasis isplaced on the problems Laotianshave with English, -

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Evaluation and Policy Analysis Unit and Regional Bureau for Asia and the Pacific

UNITED NATIONS HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR REFUGEES EVALUATION AND POLICY ANALYSIS UNIT AND REGIONAL BUREAU FOR ASIA AND THE PACIFIC Reintegration programmes for refugees in South-East Asia Lessons learned from UNHCR’s experience By Brett Ballard EPAU/2002/01 April 2002 Evaluation and Policy Analysis Unit UNHCR’s Evaluation and Policy Analysis Unit (EPAU) is committed to the systematic examination and assessment of UNHCR policies, programmes, projects and practices. EPAU also promotes rigorous research on issues related to the work of UNHCR and encourages an active exchange of ideas and information between humanitarian practitioners, policymakers and the research community. All of these activities are undertaken with the purpose of strengthening UNHCR’s operational effectiveness, thereby enhancing the organization’s capacity to fulfil its mandate on behalf of refugees and other displaced people. The work of the unit is guided by the principles of transparency, independence, consultation and relevance. Evaluation and Policy Analysis Unit United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Case Postale 2500 CH-1211 Geneva 2 Dépôt Switzerland Tel: (41 22) 739 8249 Fax: (41 22) 739 7344 e-mail: [email protected] internet: www.unhcr.org All EPAU evaluation reports are placed in the public domain. Electronic versions are posted on the UNHCR website and hard copies can be obtained by contacting EPAU. They may be quoted, cited and copied, provided that the source is acknowledged. The views expressed in EPAU publications are not necessarily those of UNHCR. The designations and maps used do not imply the expression of any opinion or recognition on the part of UNHCR concerning the legal status of a territory or of its authorities. -

Chapter Iii a Comparison on Lan Xang and Early

CHAPTER III A COMPARISON ON LAN XANG AND EARLY RATTANAKOSIN BUDDHIST ART AND ARCHITECTURAL DESIGNS As a Buddhist kingdom, both Lan Xang and Rattanakosin cherished their temples by put every effort to build one and decorate it with the most beautiful artwork they could create at that moment. Those architectures and artworks not just express how luxury each kingdom was, but also represent the thought and circumstance in the meantime. Even though Lan Xang and Rattanakosin had a same religion and were neighbor, their arts and architectural designs are different as follow: 3.1 Lan Xang Buddhist Art and Architectural Design Lan Xang was a kingdom with diversity; even in the Lao race itself. Since the end of the reign of King Suryawongsa Thammikkarat, Lan Xang was divided into three separated kingdom; Luang Prabang, Vientiane and Champasak. Even though they were split up, they still shared their art and architectural designs. Each kingdom had been influenced by the neighbor surround and outsider as described below: 3.1.1 Lan Xang Architecture Developed through centuries, Lan Xang architectures may contain a lot of outsider influence, but at some point, they have their own unique style of architecture. Lan Xang temples can be divided into two part; Buddhawat and Sangkhawat. This chapter will discusses only on the Buddhawat area which cantains of That (ธาตุ), sim (สิม), Ho Wai (หอไหว), Oob Mung (อูบมุง), Hotrai or a library (หอไตร) and Ho Klong or a drum tower (หอกลอง), 3.1.1.1 That (Pagoda or Stupa) That (ธาตุ) in Lan Xang architecture is a Buddhist monument which can refer as a Chedi or pagoda (in Thai Architecture). -

Waste Management in Nakhon Ratchasima (Korat), Thailand – Land- Fill Operation, and Leachate Treatment

Waste management in Nakhon Ratchasima (Korat), Thailand – Land- fill operation, and leachate treatment Integrated Resource Management in Asian Cities the Urban NEXUS (Water / Energy / Food Security / Land Use) UU1756 Edited by: Reported to: Dipl.-Ing.(FH) Hubert Wienands GIZ Project Dr.-Ing. Bernd Fitzke Integrated Resource Management in Asian WEHRLE Umwelt GmbH Cities: the Urban Nexus Bismarckstr. 1 – 11 United Nations, Rajadamnern Nok Avenue 79312 Emmendingen UN ESCAP Building, 5th Floor, Germany Environment and Development Division Bangkok 10200, Thailand REPORT KORAT_REV2.DOCX 1 - 20 Speicherdatum: 2015-08-26 KORAT LANDFILL SITE VISIT REPORT CONTENTS 1. ..... Introduction and Basics .......................................................................................................3 2. ..... Landfill site asessment ........................................................................................................3 2.1. Landfill data .......................................................................................................................3 2.1.1. Catchment area ............................................................................................................................................ 3 2.1.2. Site Location ................................................................................................................................................. 4 2.1.3. Side history .................................................................................................................................................. -

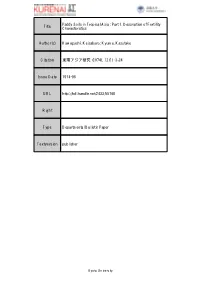

Paddy Soils in Tropical Asia : Part 1. Description of Fertility Title Characteristics

Paddy Soils in Tropical Asia : Part 1. Description of Fertility Title Characteristics Author(s) Kawaguchi, Keizaburo; Kyuma, Kazutake Citation 東南アジア研究 (1974), 12(1): 3-24 Issue Date 1974-06 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/55760 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University Southeast Asian Studies. Vol. 12, No.1, June 1974 Paddy Soils in Tropical Asia Part 1. Description of Fertility Characteristics Keizaburo KAWAGUCHI* and Kazutake KVUMA** Tropical Asia is noted as the region where more than 1/4 of the world's population today is concentrated on only 1/16 of the world's land surface. This extraordinarily high population density has been and is being supported by rice cultivation. Paddy soils are found mainly on alluvial lands such as deltas and flood plains of big rivers, coastal plains, fans and lower terraces. Their distribution among different countries in tropical Asia is shown in Table 1. 1) Annually a total of some 82 million ha of paddy land is cultivated to rice in this region of the world. As the double cropped rice area, if any, is very small, the above figure can be regarded as the total extent of paddy soils in tropical Asia. These paddy soils are mostly alluvial soils and low humic gley soils (or Entisols and Inceptisols). Grumusols (or Vertisols), reddish-brown earths (or Alfisols), red-yellow podzolic soils (or Ultisols) and latosols (or Oxisols) are also utilized, but to a limited extent. The fertility status of these different soils is naturally different. Even within one group of soils, in particular within alluvia! soils, it differs markedly depending on the nature and the degree of weathering of the parent sediments. -

1 Laos's Peripheral Centrality in Southeast Asia: Mobility, Labour

1 Laos’s Peripheral Centrality in Southeast Asia: Mobility, Labour and Regional Integration James Alan Brown School of Geography Queen Mary University of London [email protected] 2 Laos´s Peripheral Centrality in Southeast Asia: Mobility, Labour and Regional Integration Abstract Laos´s position at the centre of the Southeast Asian mainland has entailed peripherality to regional loci of power. Its geography of peripheral centrality has however resulted in Laos becoming a realm of contestation between powerful neighbours. The analysis traces the construction of Laos within a regional space from pre-colonial times to contemporary special economic zones. Laos has been produced through mobility, foreign actors´ attempts to reorient space to their sphere of influence, and transnational class relations incorporating Lao workers and peasants, Lao elites and foreign powers. These elements manifest within current special economic zone projects. Key words: Laos, regional integration, mobility, labour, special economic zones. Introduction In the past two decades, the Lao government has emphasized turning Laos from a “land- locked” to a “land-linked” country. Laos is located at the centre of mainland Southeast Asia and has been historically isolated from maritime trade routes. The vision encapsulated by the “land- linked” phrase is thus of transforming Laos´s relative geographic isolation into a centre of connectivity for the region. Laos will act as the central integrative territory which brings together other countries in the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS), facilitating commerce between them.1 The “land-locked” part of the phrase implies tropes of “Laos as a forgotten, lost, half-formed and remote land”,2 one which has historically experienced “political, territorial and military stagnation”.3 The move to a “land-linked” country can therefore be read as signifying a desire to 1 Vatthana Pholsena and Ruth Banomyong, Laos From Buffer State to Crossroads (Chiang Mai: Mekong Press, 2006), 2-3. -

Flight of Lao War Captives from Burma Back to Laos in 1596: a Comparison of Historical Sources

SOAS Bulletin of Burma Research, Vol. 3, No. 1, Spring 2005, ISSN 1479-8484 THE FLIGHT OF LAO WAR CAPTIVES FROM BURMA BACK TO LAOS IN 1596: A COMPARISON OF HISTORICAL SOURCES Jon Fernquist Mae Fa Luang University Introduction In 1596, one thousand Lao war captives fled from Pegu, the capital of the kingdom of Burma, back to their native kingdom of Lan Sang. This incident is insignificant when compared to more cataclysmic changes like the founding or fall of dynasties, but it has attracted the attention of Western, Thai, and Burmese historians since the 17th century. The incident is noteworthy and exceptional in several ways. First, the flight was to a remote destination: Laos. Second, the incident involved two traditional enemies: Burmese and ethnic Tai's. "Tai" will be used to emphasize that this is an autonomous history of pre-modern states ranging from Ayutthya in the South, through Lan Sang, Lan Na, Kengtung, and Sipsong Panna in the North, to the Shan states of Burma in the far north. Third, the entries covering the incident in the Ayutthya, Chiang Mai, and Lan Sang chronicles are short, ambiguous, and beg to be explained. All of this gives the incident great dramatic potential and two historians of note have made use of these exceptional characteristics to further their literary and ideological goals: de Marini, a Jesuit priest, in a book published in 1663, and Prince Damrong, a Thai historian, in a book published in 1917. Sections 2 and 5 will analyze the works of these historians. In other ways the incident is unexceptional. -

Isan: Regionalism in Northeastern Thailand

• ISAN•• REGIONALISM IN NORTHEASTERN THAILAND THE CORNELL UNIVERSITY SOUTHEAST ASIA PROGRAM The Southeast Asia Program was organized at Cornell University in the Department of Far Eastern Studies in 1950. It is a teaching and researdh pro gram of interdisciplinary studies in the humanities, social sciences and some natural sciences. It deals with Southeast Asia as a region, and with the in dividual countries of the area: Burma, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos,Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam. The activities of the Program are carried on both at Cornell and in Southeast Asia. They include an undergraduate and graduate curriculum at Cornell which provides instruction by specialists in South east Asian cultural history and present-day affairs, and offers intensive training in each of the major languages of the area. The Program sponsors group research projects on Thailand, on Indonesia, on the Philippines, and on the area's Chinese minorities. At the same time, individual staff and students of the Program. have done field research in every South- east Asian country. A list of publications relating to Southeast Asia which may be obtained on prepaid order directly from the Program is given at the end of this volume. Information on Program staff, fellowships, require ments for degrees, and current course offerings will be found in an Announcement of the Department of Asian Studies, obtainable from the Director, South east Asia Program, Franklin Hall, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, 14850. ISAN: REGIONALISM IN NORTHEASTERN THAILAND by Charles F. Keyes Cornell Thailand Project Interim Reports Series Number Ten Data Paper: Number 65 Southeast Asia Program Department of Asian Studies Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 1-'larch 19 6 7 Price: $2.00 Copyright CORNELL UNIVERSITY SOUTHEAST ASIA PROGRAM 1967 Second Printing 1969 FOREWORD In the erratic chaos of mainland Southeast Asia, Thai land appears to stand today as a tower of reasonable and predictable strength.