1 Laos's Peripheral Centrality in Southeast Asia: Mobility, Labour

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Waste Management in Nakhon Ratchasima (Korat), Thailand – Land- Fill Operation, and Leachate Treatment

Waste management in Nakhon Ratchasima (Korat), Thailand – Land- fill operation, and leachate treatment Integrated Resource Management in Asian Cities the Urban NEXUS (Water / Energy / Food Security / Land Use) UU1756 Edited by: Reported to: Dipl.-Ing.(FH) Hubert Wienands GIZ Project Dr.-Ing. Bernd Fitzke Integrated Resource Management in Asian WEHRLE Umwelt GmbH Cities: the Urban Nexus Bismarckstr. 1 – 11 United Nations, Rajadamnern Nok Avenue 79312 Emmendingen UN ESCAP Building, 5th Floor, Germany Environment and Development Division Bangkok 10200, Thailand REPORT KORAT_REV2.DOCX 1 - 20 Speicherdatum: 2015-08-26 KORAT LANDFILL SITE VISIT REPORT CONTENTS 1. ..... Introduction and Basics .......................................................................................................3 2. ..... Landfill site asessment ........................................................................................................3 2.1. Landfill data .......................................................................................................................3 2.1.1. Catchment area ............................................................................................................................................ 3 2.1.2. Site Location ................................................................................................................................................. 4 2.1.3. Side history .................................................................................................................................................. -

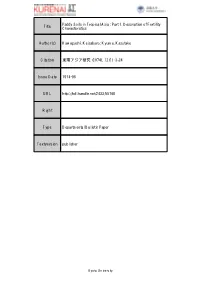

Paddy Soils in Tropical Asia : Part 1. Description of Fertility Title Characteristics

Paddy Soils in Tropical Asia : Part 1. Description of Fertility Title Characteristics Author(s) Kawaguchi, Keizaburo; Kyuma, Kazutake Citation 東南アジア研究 (1974), 12(1): 3-24 Issue Date 1974-06 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/55760 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University Southeast Asian Studies. Vol. 12, No.1, June 1974 Paddy Soils in Tropical Asia Part 1. Description of Fertility Characteristics Keizaburo KAWAGUCHI* and Kazutake KVUMA** Tropical Asia is noted as the region where more than 1/4 of the world's population today is concentrated on only 1/16 of the world's land surface. This extraordinarily high population density has been and is being supported by rice cultivation. Paddy soils are found mainly on alluvial lands such as deltas and flood plains of big rivers, coastal plains, fans and lower terraces. Their distribution among different countries in tropical Asia is shown in Table 1. 1) Annually a total of some 82 million ha of paddy land is cultivated to rice in this region of the world. As the double cropped rice area, if any, is very small, the above figure can be regarded as the total extent of paddy soils in tropical Asia. These paddy soils are mostly alluvial soils and low humic gley soils (or Entisols and Inceptisols). Grumusols (or Vertisols), reddish-brown earths (or Alfisols), red-yellow podzolic soils (or Ultisols) and latosols (or Oxisols) are also utilized, but to a limited extent. The fertility status of these different soils is naturally different. Even within one group of soils, in particular within alluvia! soils, it differs markedly depending on the nature and the degree of weathering of the parent sediments. -

Isan: Regionalism in Northeastern Thailand

• ISAN•• REGIONALISM IN NORTHEASTERN THAILAND THE CORNELL UNIVERSITY SOUTHEAST ASIA PROGRAM The Southeast Asia Program was organized at Cornell University in the Department of Far Eastern Studies in 1950. It is a teaching and researdh pro gram of interdisciplinary studies in the humanities, social sciences and some natural sciences. It deals with Southeast Asia as a region, and with the in dividual countries of the area: Burma, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos,Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam. The activities of the Program are carried on both at Cornell and in Southeast Asia. They include an undergraduate and graduate curriculum at Cornell which provides instruction by specialists in South east Asian cultural history and present-day affairs, and offers intensive training in each of the major languages of the area. The Program sponsors group research projects on Thailand, on Indonesia, on the Philippines, and on the area's Chinese minorities. At the same time, individual staff and students of the Program. have done field research in every South- east Asian country. A list of publications relating to Southeast Asia which may be obtained on prepaid order directly from the Program is given at the end of this volume. Information on Program staff, fellowships, require ments for degrees, and current course offerings will be found in an Announcement of the Department of Asian Studies, obtainable from the Director, South east Asia Program, Franklin Hall, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, 14850. ISAN: REGIONALISM IN NORTHEASTERN THAILAND by Charles F. Keyes Cornell Thailand Project Interim Reports Series Number Ten Data Paper: Number 65 Southeast Asia Program Department of Asian Studies Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 1-'larch 19 6 7 Price: $2.00 Copyright CORNELL UNIVERSITY SOUTHEAST ASIA PROGRAM 1967 Second Printing 1969 FOREWORD In the erratic chaos of mainland Southeast Asia, Thai land appears to stand today as a tower of reasonable and predictable strength. -

05 Chalong 111-28 111 2/25/04, 1:54 PM CHALONG SOONTRAVANICH

CONTESTING VISIONS OF THE LAO PAST i 00 Prelims i-xxix 1 2/25/04, 4:48 PM NORDIC INSTITUTE OF ASIAN STUDIES NIAS Studies in Asian Topics 15. Renegotiating Local Values Merete Lie and Ragnhild Lund 16. Leadership on Java Hans Antlöv and Sven Cederroth (eds) 17. Vietnam in a Changing World Irene Nørlund, Carolyn Gates and Vu Cao Dam (eds) 18. Asian Perceptions of Nature Ole Bruun and Arne Kalland (eds) 19. Imperial Policy and Southeast Asian Nationalism Hans Antlöv and Stein Tønnesson (eds) 20. The Village Concept in the Transformation of Rural Southeast Asia Mason C. Hoadley and Christer Gunnarsson (eds) 21. Identity in Asian Literature Lisbeth Littrup (ed.) 22. Mongolia in Transition Ole Bruun and Ole Odgaard (eds) 23. Asian Forms of the Nation Stein Tønnesson and Hans Antlöv (eds) 24. The Eternal Storyteller Vibeke Børdahl (ed.) 25. Japanese Influences and Presences in Asia Marie Söderberg and Ian Reader (eds) 26. Muslim Diversity Leif Manger (ed.) 27. Women and Households in Indonesia Juliette Koning, Marleen Nolten, Janet Rodenburg and Ratna Saptari (eds) 28. The House in Southeast Asia Stephen Sparkes and Signe Howell (eds) 29. Rethinking Development in East Asia Pietro P. Masina (ed.) 30. Coming of Age in South and Southeast Asia Lenore Manderson and Pranee Liamputtong (eds) 31. Imperial Japan and National Identities in Asia, 1895–1945 Li Narangoa and Robert Cribb (eds) 32. Contesting Visions of the Lao Past Christopher E. Goscha and Søren Ivarsson (eds) ii 00 Prelims i-xxix 2 2/25/04, 4:48 PM CONTESTING VISIONS OF THE LAO PAST LAO HISTORIOGRAPHY AT THE CROSSROADS EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER E. -

Paddy Soils in Tropical Asia

Southeast Asian Studies. Vol. 12, No.1, June 1974 Paddy Soils in Tropical Asia Part 1. Description of Fertility Characteristics Keizaburo KAWAGUCHI* and Kazutake KVUMA** Tropical Asia is noted as the region where more than 1/4 of the world's population today is concentrated on only 1/16 of the world's land surface. This extraordinarily high population density has been and is being supported by rice cultivation. Paddy soils are found mainly on alluvial lands such as deltas and flood plains of big rivers, coastal plains, fans and lower terraces. Their distribution among different countries in tropical Asia is shown in Table 1. 1) Annually a total of some 82 million ha of paddy land is cultivated to rice in this region of the world. As the double cropped rice area, if any, is very small, the above figure can be regarded as the total extent of paddy soils in tropical Asia. These paddy soils are mostly alluvial soils and low humic gley soils (or Entisols and Inceptisols). Grumusols (or Vertisols), reddish-brown earths (or Alfisols), red-yellow podzolic soils (or Ultisols) and latosols (or Oxisols) are also utilized, but to a limited extent. The fertility status of these different soils is naturally different. Even within one group of soils, in particular within alluvia! soils, it differs markedly depending on the nature and the degree of weathering of the parent sediments. Naturally, these differences in fertility result in the differences in productivity of rice. This is particularly true for the extensive agriculture as practised in tropical Asia today. -

REVIEW of the CONTINENTAL MESOZOIC STRATIGRAPHY of THAILAND Nares Sattayarak Mineral Fuels Division Department of Mineral Resources Bangkok 10400, Thailand

WORKSHOP ON STRATIGRAPHIC CORRELATION OF THAILAND AND MALAYSIA Haad Yai, Thailand 8-10 Septdber, 1983 REVIEW OF THE CONTINENTAL MESOZOIC STRATIGRAPHY OF THAILAND Nares Sattayarak Mineral Fuels Division Department of Mineral Resources Bangkok 10400, Thailand IRTRODUCTIOH The continental Mesozoic redbeds are widely distributed throughout the country, especially in the Khorat Plateau, from which the group's name was obtained. The rocks are predominantly red clastic, i.e. , sandstone, silt stone, claystone, shale and conglomerate. The Khorat Group rests. uncon formably on older rocks, generally of Paleozoic age, but occasionally it overlies the Permo-Triassic igneous rocks and/or Lower to Middle Triassic sedimentary rocks. The Khorat Group was previously reviewed in Thai by Nakornsri (1975) and in English by Kulasing ( 1975) and Ramingwong ( 1978) • This paper is an attempt to update the knowledge so far reported about the Khorat rocks and their equivalents. REVIEW OF PREVIOUS WORKS Lee (1923) was the first geologist who noted the non-marine Mesozoic rocks in the Khorat Plateau and divided them into Upper and Lower Group, the Triassic age was given. Brown et al. ( 1953) named the IChorat Series to represent the conti nental redbeds and the marine Triassic limestone of northern Thailand. The sequence consists of interbedded sandstone, conglomerate, shale and marly limestone. No fossil was found except some petrified wood. La Moreaux et al. (1956) divided the Khorat Series, following Chali chan and Bunnag ( 1954) , into three members and assigned the age of this sequence to the Triassic period. Their subdivision are as follows: Phu Kradung Member is the oldest member it lies unconformably on Paleozoic rocks. -

Title IRON and SALT INDUSTRIES in ISAN Author(S)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository Title IRON AND SALT INDUSTRIES IN ISAN Author(s) NITTA, Eiji 重点領域研究総合的地域研究成果報告書シリーズ : 総合 Citation 的地域研究の手法確立 : 世界と地域の共存のパラダイム を求めて (1996), 30: 43-66 Issue Date 1996-11-30 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/187676 Right Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University IRON AND SALT INDUSTRIES IN ISAN Eiji NITTA Kagoshima University Isan is now a poor country. But it was once a rich and civilized country in the ancient times. Dense distribution of archaeological sites proves the existence of the economic basis that supported dense population and wealthy societies in northeast Thailand. Recent archaeological surveys and excavations conducted by Southeast Asian and foreign archaeologists including the author suggest that prehistoric industries such as bronze and iron-working, and salt-making activities adaptive for the environment and the ecosystem in the northeast were the important background to support the prosperity and the urbanization of the ancient societies besides rice cultivation and forest products. Mekhong River and the Mekhong basin played important transportation route for the local economic centers. This is a revised paper which was presented at the seminar in Bangkok in 1994. 1. Background The northeast is a plateau called Khorat Plateau. This plateau is formed by the Khorat Mesozoic sedimentary rock. There was a sea in the Mesozoic more than one hundred fifty millionyears ago. The upheaval in the Tertiary period sealed the sea water in this area. Very thick rock salt layer that originates from the sealed sea water exists deep underground in the Khorat Plateau. -

Chapter Ii Literature Review

CHAPTER II LITERATURE REVIEW 2.1 Introduction This chapter is comprised of literature review of geology and petroleum geology in northeastern Thailand. The related knowledges are categorized into groups including general geology, stratigraphy, basin evalution, structural framework, petroleum provinces, petroleum prospect in Permian basin play, seismic interpretation of the Chonnabot prospect, subsurface structural map of the Permian play, petroleum geochemistry evaluation of Permian carbonate rock, carbonate reservoir characterization, and seal and trap rock characterization. 2.2 General geology The northeastern region of Thailand is located between latitudes 14o to 19o North and longitudes 101o to 106o East, covering an area abount one third of the country or abount 200,000 square kilometers. The northern and eastern border is bounded by the Lao People’s Democratic Republic (Laos) and the Mekong river. The southern part is connected to the Democratic Kamphuchea and the western part is bounded by certral and northern of Thailand. The Khorat Plateau forms a part of the Indochina plate bounded by major Tertiary strike-slip faults. Althought several tectonic models indicate that the Khorat Plateau is largely underformed. It contains two fold belts; the N-S trending Loei- Phetchabun foldfold beltbelt inin thethe western western area area and and NW-SE NW-SE trending trending Phu Phu Phan Phan range range in inthe the 8 central part which divided the central plain in the northern Sakhon Nakhon basin, and the southern Khorat basin. General geology of the area and the sedimentary sequence consists of an initial rift sequence of Carboniferous to Triassic sediments and a sag sequence of Late Triassic to Cretaceous sediments that consisted of Khorat Group which is mainly sedimentary subsequence (Figure 2.1). -

On the Verge of the Mekong River Environment

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Saitama University Cyber Repository of Academic Resources Special Issue on Mekong Economy, the Social Science Review, Saitama University, Japan, March 2019. 《Chapter 4》 Sustainable Development On the verge of the Mekong River Environment Takashi Asaeda1 Received: 1 September 2018 / Accepted: 20 October 2018 © Social Science Review (2018) Saitama University, Japan Abstract This paper aims to argue the extreme fragility of the ecosystem in the Lower Mekong Basin in the process of economic development in the Mekong region. The Lower Mekong Basin has been proud of its richness in nature and high biodiversity. The Basin’s ecosystem has, however, been endangered by the recent development factors such as the dam construction. The dam construction gives negative impacts on the river basin’s fish biodiversity. The dam also traps and curtails almost of all sediment flow to the downstream. The reduced sediment transport would result in the shrinkage of the delta area in Vietnam most seriously, where the channel bet would be eroded and much saltwater would be introduced into the river channel. In a couple of decades later, the modification just for the economic growth may change the river as an artificial unproductive channel. Keywords Mekong River Environment, Ecosystem, Fish biodiversity, Dam construction, Sediment flow. JEL Classification Q57, 3O53 1 Graduate School of Science and Engineering, Saitama University E-mail: [email protected] 135 Special Issue on Mekong Economy, the Social Science Review, Saitama University, Japan, March 2019. 1 Introduction The Mekong is the tenth-largest river by volume in the world. -

Meteorological Drought Analysis in the Lower Mekong Basin Using Satellite-Based Long-Term CHIRPS Product

sustainability Article Meteorological Drought Analysis in the Lower Mekong Basin Using Satellite-Based Long-Term CHIRPS Product Hao Guo 1,2,3,4, Anming Bao 1,4,*, Tie Liu 1,4, Felix Ndayisaba 1,2,5, Daming He 6, Alishir Kurban 1,4 and Philippe De Maeyer 3,4 1 State Key Laboratory of Desert and Oasis Ecology, Xinjiang Institute of Ecology and Geography, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Urumqi 830011, China; [email protected] (H.G.); [email protected] (T.L.); [email protected] (F.N.); [email protected] (A.K.) 2 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100039, China 3 Department of Geography, Ghent University, Gent 9000, Belgium; [email protected] 4 Sino-Belgian Joint Laboratory of Geo-information, Urumqi 830011, China and Ghent 9000, Belgium 5 University of Lay Adventists of Kigali (UNILAK), 6392 Kigali, Rwanda 6 Asian International Rivers Center, Yunnan University, Kunming 650091, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-0991-788-5378 Academic Editor: Audrey Mayer Received: 9 May 2017; Accepted: 25 May 2017; Published: 29 May 2017 Abstract: Lower Mekong Basin (LMB) experiences a recurrent drought phenomenon. However, few studies have focused on drought monitoring in this region due to lack of ground observations. The newly released Climate Hazards Group Infrared Precipitation with Station data (CHIRPS) with a long-term record and high resolution has a great potential for drought monitoring. Based on the assessment of CHIRPS for capturing precipitation and monitoring drought, this study aims to evaluate the drought condition in LMB by using satellite-based CHIRPS from January 1981 to July 2016. -

The Creation of Heritage in Vientiane, Laos

STUDIES IN GLOBAL ARCHAEOLOGY 13 PRESERVING IMPERMANENCE THE CREATION OF HERITAGE IN VIENTIANE, LAOS ANNA KARLSTRÖM Department of Archaeology and Ancient History Uppsala University 2009 Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Geijersalen, Centre for the Humanities, English Park Campus, Thunbergsvägen 3P, Uppsala, Saturday, June 6, 2009 at 13:00 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Abstract Karlström, A. 2009. Preserving Impermanence. The Creation of Heritage in Vientiane, Laos. Studies in Global Archaeology 13. 239 pp. 978-91-506-2077-1. This thesis is about the heritage in Vientiane. In an attempt to go beyond a more traditional descriptive approach, the study aims at bringing forward a discussion about the definition, or rather the multiplicity of definitions, of the concept of heritage as such. The unavoidabe tension emanating from a modern western frame of thought being applied to the geographical and cultu- ral setting of the study provides an opportunity to develop a criticism of some of the assumptions underlying our current definitions of heritage. For this particular study, heritage is defined as to include stories, places and things. It is a heri- tage that is complex and ambiguous, because the stories are parallel, the definitions and percep- tions of place are manifold and contested, and the things and their meaning appear altered, de- pending on what approach to materiality is used. The objective is not to propose how to identify and manage such a complex heritage. Rather, it is about what causes this complexity and ambi- guity and what is in between the stories, places and things. -

The Relevance of Contemporary Bronze Casting in Ubon

THE RELEVANCE OF CONTEMPORARY BRONZE CASTING IN UBON, THAILAND FOR UNDERSTANDING THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL RECORD OF THE BRONZE AGE IN PENINSULAR SOUTHEAST ASIA A Thesis by DANIEL EUGENE EVERLY Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December 2004 Major Subject: Anthropology THE RELEVANCE OF CONTEMPORARY BRONZE CASTING IN UBON, THAILAND FOR UNDERSTANDING THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL RECORD OF THE BRONZE AGE IN PENINSULAR SOUTHEAST ASIA A Thesis by DANIEL EUGENE EVERLY Submitted to Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved as to style and content by: _____________________________ _____________________________ D. Bruce Dickson Norbert Dannhaeuser (Chair of Committee) (Member) _____________________________ ___________________________ Edward Runge David Carlson (Member) (Head of Department) December 2004 Major Subject: Anthropology iii ABSTRACT The Relevance of Contemporary Bronze Casting in Ubon, Thailand for Understanding the Archaeological Record of the Bronze Age in Peninsular Southeast Asia. (December 2004) Daniel Eugene Everly, B.S., University of Houston; M.A., University of Houston at Clear Lake Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. D. Bruce Dickson A direct historical approach is used in this thesis to document the lost wax casting technique as currently practiced by indigenous metallurgists in northeastern Thailand. The smiths observed at Ban Pba Ao, Ubon Ratchathani Province are the last practicing members of a bronze working tradition that has been in continuous operation at the village for two centuries. An account of the processes used to create bronze bells is provided. Of particular significance is the fact that the yard in which casting activities are performed did not receive clean up operations following the bells production.