Context, Structure, and Meaning in the Scottish Ballad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Or Download Full Colour Catalogue May 2021

VIEW OR DOWNLOAD FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE 1986 — 2021 CELEBRATING 35 YEARS Ian Green - Elaine Sunter Managing Director Accounts, Royalties & Promotion & Promotion. ([email protected]) ([email protected]) Orders & General Enquiries To:- Tel (0)1875 814155 email - [email protected] • Website – www.greentrax.com GREENTRAX RECORDINGS LIMITED Cockenzie Business Centre Edinburgh Road, Cockenzie, East Lothian Scotland EH32 0XL tel : 01875 814155 / fax : 01875 813545 THIS IS OUR DOWNLOAD AND VIEW FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE FOR DETAILS OF AVAILABILITY AND ON WHICH FORMATS (CD AND OR DOWNLOAD/STREAMING) SEE OUR DOWNLOAD TEXT (NUMERICAL LIST) CATALOGUE (BELOW). AWARDS AND HONOURS BESTOWED ON GREENTRAX RECORDINGS AND Dr IAN GREEN Honorary Degree of Doctorate of Music from the Royal Conservatoire, Glasgow (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – The Hamish Henderson Award for Services to Traditional Music (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – Hall of Fame (Ian Green) East Lothian Business Annual Achievement Award For Good Business Practises (Greentrax Recordings) Midlothian and East Lothian Chamber of Commerce – Local Business Hero Award (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Hands Up For Trad – Landmark Award (Greentrax Recordings) Featured on Scottish Television’s ‘Artery’ Series (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Honorary Member of The Traditional Music and Song Association of Scotland and Haddington Pipe Band (Ian Green) ‘Fuzz to Folk – Trax of My Life’ – Biography of Ian Green Published by Luath Press. Music Type Groups : Traditional & Contemporary, Instrumental -

Lyrics + Detailed Song N...Or MMFLBF

Extended Liner Notes and Lyrics for My Mind From Love Being Free by Lindsay Straw Since so many of these songs were learned primarily from three singers, I feel that it’s worth elaborating a bit on each. Lizzie Higgins & Jeannie Robertson: Nearly half come from the Scottish musical dynasty of Jeannie Robertson and Lizzie Higgins: “Far Over the Forth,” “Lord Lovat,” “When I Was Not But Sweet Sixteen,” and “Lovely Molly.” Jeannie and Lizzie’s powerful, emotional singing styles and repertoire continue to move me, years after stumbling upon them in the Voice of the People collections. Jeannie Robertson was a major figure in the British folk revival. She and her family were Travellers in Aberdeenshire, and were bearers of a rich musical history. Her daughter Lizzie reluctantly performed and recorded Jeannie’s songs and carried on her legacy, as did many other singers who learned from her over the years. Musical Traditions’ In Memory of Lizzie Higgins and James Porter & Herschel Gower’s Jeannie Robertson: Emergent Singer, Transformative Voice, along with the Mainly Norfolk website, have been invaluable resources for further exploring both the songs and singers. Rita Gallagher: Several songs “The Bonny Light Horseman,” “The Mermaid,” and “Lurgy Stream” were learned from Rita Gallagher’s albums. Rita’s gorgeous voice and intricate ornamentation are hugely responsible for my love of oldstyle Irish singing. Rita is from Donegal, and when she was younger she learned from Paddy Tunney and other members of his family. She has also been kind enough to take the time to answer a nerdy folk singer’s questions via email. -

INTERPRETING POETRY: English and Scottish Folk Ballads (Year 5, Day Department, 2016) Assignments for Self-Study (25 Points)

The elective discipline «INTERPRETING POETRY: English and Scottish Folk Ballads (Year 5, day department, 2016) Assignments for Self-Study (25 points) Task: Select one British folk ballad from the list below, write your name, perform your individual scientific research paper in writing according to the given scheme and hand your work in to the teacher: Titles of British Folk Ballads Students’ Surnames 1. № 58: “Sir Patrick Spens” 2. № 13: “Edward” 3. № 84: “Bonny Barbara Allen” 4. № 12: “Lord Randal” 5. № 169:“Johnie Armstrong” 6. № 243: “James Harris” / “The Daemon Lover” 7. № 173: “Mary Hamilton” 8. № 94: “Young Waters” 9. № 73:“Lord Thomas and Annet” 10. № 95:“The Maid Freed from Gallows” 11. № 162: “The Hunting of the Cheviot” 12. № 157 “Gude Wallace” 13. № 161: “The Battle of Otterburn” 14. № 54: “The Cherry-Tree Carol” 15. № 55: “The Carnal and the Crane” 16. № 65: “Lady Maisry” 17. № 77: “Sweet William's Ghost” 18. № 185: “Dick o the Cow” 19. № 186: “Kinmont Willie” 20. № 187: “Jock o the Side” 21. №192: “The Lochmaben Harper” 22. № 210: “Bonnie James Campbell” 23. № 37 “Thomas The Rhymer” 24. № 178: “Captain Car, or, Edom o Gordon” 25. № 275: “Get Up and Bar the Door” 26. № 278: “The Farmer's Curst Wife” 27. № 279: “The Jolly Beggar” 28. № 167: “Sir Andrew Barton” 29. № 286: “The Sweet Trinity” / “The Golden Vanity” 30. № 1: “Riddles Wisely Expounded” 31. № 31: “The Marriage of Sir Gawain” 32. № 154: “A True Tale of Robin Hood” N.B. You can find the text of the selected British folk ballad in the five-volume edition “The English and Scottish Popular Ballads: five volumes / [edited by Francis James Child]. -

Sheila Stewart

Sheila, Belle and Jane Turriff. Photo: Alistair Chafer “…Where would Sheila Stewart the ballad singing Scottish Traveller, Traditional Singer and Storyteller tradition in Scotland 1935 - 2014 be today without the unbroken continuity by Pete Shepheard of tradition passed on to us by Sheila and other members of Scotland’s ancient Traveller community…” “…one of Scotland’s finest traditional singers, inheriting The family was first brought to When berry time comes roond look for the Stewarts who rented Traveller lore and balladry from all light by Blairgowrie journalist each year, Blair’s population’s berry fields at the Standing Stones sides of her family, and learning a rich oral culture Maurice Fleming in 1954 following swellin, at Essendy. So he cycled up to songs from her mother, some of a chance meeting with folklorist There’s every kind o picker there Essendy and it was Sheila Stewart the most interesting, and oldest, of songs, ballads Hamish Henderson in Edinburgh. and every kind o dwellin; he met (just 18 years old at the songs in her repertoire came from Discovering that Hamish had There’s tents and huts and time) who immediately said she Belle’s brother, her uncle, Donald caravans, there’s bothies and and folk tales that recently been appointed as a knew the song and told Maurice MacGregor, who carefully taught there’s bivvies, research fellow at the School it had been written by her mother her the ballads. Donald could had survived as And shelters made wi tattie-bags Belle. Maurice reported the of Scottish Studies, Maurice neither read nor write, but was an and dug-outs made wi divvies. -

Oral Tradition 29.1

Oral Tradition, 29/1 (2014):47-68 Voices from Kilbarchan: Two versions of “The Cruel Mother” from South-West Scotland, 1825 Flemming G. Andersen Introduction It was not until the early decades of the nineteenth century that a concern for preserving variants of the same ballad was really taken seriously by collectors. Prior to this ballad editors had been content with documenting single illustrations of ballad types in their collections; that is, they gave only one version (and often a “conflated” or “amended” one at that), such as for instance Thomas Percy’s Reliques of Ancient English Poetry from 1765 and Walter Scott’s Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border from 1802. But with “the antiquarian’s quest for authenticity” (McAulay 2013:5) came the growing appreciation of the living ballad tradition and an interest in the singers themselves and their individual interpretations of the traditional material. From this point on attention was also given to different variations of the same ballad story, including documentation (however slight) of the ballads in their natural environment. William Motherwell (1797-1835) was one of the earliest ballad collectors to pursue this line of collecting, and he was very conscious of what this new approach would mean for a better understanding of the nature of an oral tradition. And as has been demonstrated elsewhere, Motherwell’s approach to ballad collecting had an immense impact on later collectors and editors (see also, Andersen 1994 and Brown 1997). In what follows I shall first give an outline of the earliest extensively documented singing community in the Anglo-Scottish ballad tradition, and then present a detailed analysis of two versions of the same ballad story (“The Cruel Mother”) taken down on the same day in 1825 from two singers from the same Scottish village. -

LAMENT the Fruits of Diverse Languages and Aesthetic Values, These Traditions Are Rooted in Strikingly Different Landscapes

Traditional Song and Music in Scotland MARGARET BENNETT 77 The traditional songs, poetry, and musiC of Scotland are as easy to recognize as they are difficult to define. Just as purple heather cannot describe the whole country, so with traditional arts: no simple description will fit. M A C C R I M M 0 N ' S LAMENT The fruits of diverse languages and aesthetic values, these traditions are rooted in strikingly different landscapes. Within this small country there are enormous Dh'iadh ceo nan stuc mu contrasts. Culturally as well as geographically, Scotland could be divided aodainn Chuillionn, Is sheinn a' bhean-shith a torman into several (imaginary) areas [see map on page 70], each reflecting a mulaid, distinct spirit of the Scottish people, their songs, poetry, and music. Gorm shuilean ciuin san Along with the Western Isles (the Outer Hebrides), the Highlands Dun a' sileadh Scotland's largest land mass and most sparsely populated area-is On thriall thu uainn 's nach till traditionally home to the Gaels, who make their living from "crofting" thu tuille. (working very small farms), fishing, weaving, whisky distilling, tourism, Cha till, cha till, cha till and, nowadays, computing. uciamar a tha thu'n diugh?" a neighbor MacCriomain, enquires, in Scottish Gaelic, "How are you today?" The songs and music An cogadh no s.ith cha till e have evolved through history, from as early as the first century C.E., when tuille; Scotland and Ireland shared traditions about their heroes. These traditions Le airgiod no ni cha till MacCriomain remember the hero Cu Culainn, whose warriors were trained to fight by Cha till e gu bdth gu La na a formidable woman on the Isle of Skye. -

The English Occupational Song

UNIVERSITY OF UMEÅ DISSERTATION ISSN 0345-0155-ISBN 91-7174-649-8 From the Department of English, Faculty of Humanities, University of Umeå, Sweden. THE ENGLISH OCCUPATIONAL SONG AN ACADEMIC DISSERTATION which will, on the proper authority of the Chancellor's Office of Umeå University for passing the doctoral examination, be publicly defended in Hörsal E, Humanisthuset, on Saturday, May 23, at 10 a.m. Gerald Porter University of Umeå Umeå 1992 ABSTRACT THE ENGLISH OCCUPATIONAL SONG. Gerald Porter, FL, Department of English, University of Umeå, S 901 87, Sweden. This is the first full-length study in English of occupational songs. They occupy the space between rhythmic work songs and labour songs in that the occupation signifies. Occupation is a key territorial site. If the métier of the protagonist is mentioned in a ballad, it cannot be regarded as merely a piece of illustrative detail. On the contrary, it initiates a powerful series of connotations that control the narrative, while the song's specific features are drawn directly from the milieu of the performer. At the same time, occupational songs have to exist in a dialectical relationship with their milieu. On the one hand, they aspire to express the developing concerns of working people in a way that is simultaneously representational and metaphoric, and in this respect they display relative autonomy. On the other, they are subject to the mediation of the dominant or hegemonic culture for their dissemination. The discussion is song-based, concentrating on the occupation group rather than, as in several studies of recent years, the repertoire of a singer or the dynamics of a particular performance. -

Download PDF Booklet

THE TRAVELLING STEWARTS 1 Johnnie, My Man Lizzie Higgins 2 Willie’s Fatal Visit Jeannie Robertson 3 The Battle’s O’er; Scotland the Brave; The 51st Division in Egypt Played by Donald and Isaac Higgins, pipes 4 Bogie’s Bonnie Belle Jane Stewart 5 McGinty’s Meal and Ale Davy Stewart 6 My Bonnie Tammy Christina Stewart 7 MacPherson’s Lament Maggie McPhee 8 The Drunken Piper; Brig o’ Perth; Reel o’ Tulloch Played by Alex Stewart, pipes 9 Loch Dhui Belle Stewart acc. Alex Stewart, goose 10 The Dawning of the Day Cathie Stewart, acc. Alex Stewart, goose 11 Donald’s Return to Glencoe Sheila Stewart First Issued by Topic 1968. Recorded in Scotland by Bill Leader, 1967. Notes by Carl MacDougall Photograph by Brian Shuel ‘You’ll never see me laughing or shouting at a Pakistani or Later the mass evictions of Highland crofters now anybody like that; no, never... known as the Clearances, where sheep usurped men in the Long, long years ago when I was a wee boy. my auld mother minds of the land-owners, helped swell the ranks of the told me that all travellers came from the same place as these ‘travellers’. The evictions were followed by an orgy of tartan people. and so I never do anything that might offend them. romanticism which we Scots have not yet recovered from; and Anyway, they`re having a hard time of it. just like the this was followed by an orgy of ‘gypsy’ romanticism. Just as travellers...’ every Scot had a kindly, tartan-clad granny in a wee cottage Davy Stewart, itinerant singer. -

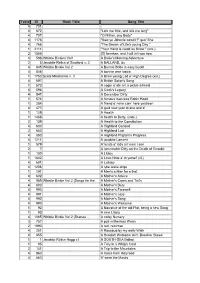

Table ID Book Titile Song Title 4

Table ID Book Titile Song Title 4 701 - 4 672 "Lo'e me little, and lo'e me lang" 4 707 "O Mither, ony Body" 4 1176 "Saw ye Johnnie comin'?" quo' She 4 766 "The Dream of Life's young Day " 1 2111 "Your Hand is cauld as Snaw " (xxx.) 2 1555 [O] hearken, and I will tell you how 4 596 Whistle Binkies Vol1 A Bailie's Morning Adventure 2 5 Jacobite Relics of Scotland v. 2 A BALLAND, &c 4 845 Whistle Binkie Vol 2 A Bonnie Bride is easy buskit 4 846 A bonnie wee lassie 1 1753 Scots Minstrelsie v. 3 A Braw young Lad o' High Degree (xxi.) 4 597 A British Sailor's Song 1 573 A cogie o' ale an' a pickle aitmeal 4 598 A Cook's Legacy 4 847 A December Dirty 1 574 A famous man was Robin Hood 1 284 A friend o' mine cam' here yestreen 4 477 A guid new year to ane and a' 1 129 A Health 1 1468 A health to Betty, (note,) 2 139 A Health to the Constitution 4 600 A Highland Garland 2 653 A Highland Lad 4 850 A Highland Pilgram's Progress 4 1211 A jacobite Lament 1 579 A' kinds o' lads an' men I see 2 7 A lamentable Ditty on the Death of Geordie 1 130 A Litany 1 1842 A Love-Note a' to yersel' (xi.) 4 601 A Lullaby 4 1206 A lyke wake dirge 1 291 A Man's a Man for a that 4 602 A Mother's Advice 4 989 Whistle Binkie Vol 2 (Songs for the A Mother's Cares and Toil's 4 603 Nursery) A Mother's Duty 4 990 A Mother's Farewell 4 991 A Mother's Joys 4 992 A Mother's Song 4 993 A Mother's Welcome 1 92 A Narrative of the old Plot; being a new Song 1 93 A new Litany 4 1065 Whistle Binkie Vol 2 (Scenes … A noisy Nursery 3 757 Nursery) A puir mitherless Wean 2 1990 A red, red rose 4 251 A Rosebud by my early Walk 4 855 A Scottish Welcome to H. -

9972508.PDF (6.393Mb)

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter ^ce, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy subm itted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographicaily in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMI UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE JEAN RITCHIE’S FIELD TRIP - SCOTLAND: AN EXAMINATION OF UNPUBLISHED FIELD RECORDINGS COLLECTED IN SCOTLAND, 1952-53 A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By SUSAN HENDRIX BRUMFIELD Norman, Oklahoma 2000 UMI Number 9972508 UMI UMI Microform9972508 Copyright 2000 by Bell & Howell Information and Learning Company. -

Honoured At2015 and He Is from the Island of South Uist

& Wffiffiffifu7#uryffiY"?'ffi{}q4Y*Y#,83;4 tf,rlft 5ill{8 {, L*f'tqq#ttr l$fft The l TthAnnual Grandfather Mountain Gaelic Song and Language Week will be held again this year at Lees-MacRae College in Banner Elk, North Caro- lina from July 5, 201 5 until July 10, 2015. Gill ebr i de Mac Mill an, w ho pl ay s Gwyllyn the The week consists of Scottish Gaelic language B ar d i n t he Outlander te I ev i s i o n s e r i e s on St ar z w ill and song classes for all from complete beginners to - be at the Gaelic Song & Language Week this July advanced speakers. at Gr andfather Mountain., The song classes will cover arange oftraditional Gaelic song forms. You don't need to be fluent in Gaelic to learn Clan Henderson Gaelic songs! Instructors this yearwill be Gillebride MacMillan, Joy Dunlop, and Kathleen Reddy. Gillebride MacMillan's first language is Gaelic, honoured at2015 and he is from the island of South Uist. He plays the role of Gwyllyn the Bard in the Outlander television Savannah Games series on Starz. He is well known as a singer, teacher andtranslator. The Clan Henderson is the honoured Joy Dunlop is both an award-winning singer and clan at the 39th annual Savannah Scottish step-dancer from S cotland. Games on Sat, May 2"d ,2075. Kathleen Reddy is a certified Gaelic instructor Show Henderson pride and join your who teaches Gaelic at St. Francis Xavier University in clan that day! Steve Henderson will be Nova Scotia. -

THE EDINBURGH COMPANION to SCOTTISH WOMEN's WRITING WRITING EDITED by GLENDA NORQUAY Xxxxxxxxxx EDITED by GLENDA NORQUAY Glenda Norquay Xxxxx EDITED by GLENDA NORQUAY

EDINBURGH COMPANIONS THE EDINBURGH COMPANION TO TO SCOTTISH LITERATURE WRITING WOMEN'S SCOTTISH THE EDINBURGH SERIES EDITORS: IAN BROWN & THOMAS OWEN CLANCY COMPANION TO This series offers new insights into Scottish authors, periods and topics drawing on contemporary critical approaches. Each volume: • provides a critical evaluation and comprehensive overview of its subject SCOTTISH • offers thought-provoking original critical assessments by expert contributors • includes a general introduction by the volume editor(s) and a selected guide to further reading. WOMEN'S THE EDINBURGH COMPANION TO SCOTTISH WOMEN'S WRITING WRITING EDITED BY GLENDA NORQUAY xxxxxxxxxx EDITED BY GLENDA NORQUAY Glenda Norquay xxxxx EDITED BY GLENDA NORQUAY GLENDA BY EDITED ISBN 978-0-7486-4431-5 ISBN 978 0 7486 4431 5 Edinburgh University Press 22 George Square E dinburgh Edinburgh EH8 9LF Cover image: Still Life www.euppublishing.com © Margaretann Bennett Cover design: www.paulsmithdesign.com www.margaretannbennett.co.uk The Edinburgh Companion to Scottish Women’s Writing NORQUAY PRINT.indd i 10/05/2012 11:24 Edinburgh Companions to Scottish Literature Series Editors: Ian Brown and Thomas Owen Clancy Titles in the series include: The Edinburgh Companion to Robert Burns The Edinburgh Companion to Scottish Drama Edited by Gerard Carruthers Edited by Ian Brown 978 0 7486 3648 8 (hardback) 978 0 7486 4108 6 (hardback) 978 0 7486 3649 5 (paperback) 978 0 7486 4107 9 (paperback) The Edinburgh Companion to Twentieth- The Edinburgh Companion to Sir Walter Scott Century