Innocence and Guilt Detection in High-Stakes Television Appeals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Membrane Disrupting Antimicrobial Peptide Dendrimers with Multiple Amino Termini

Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Medicinal Chemistry Communications This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2011 S1 Supporting Information for: Membrane disrupting antimicrobial peptide dendrimers with multiple amino termini Michaela Stach, a) Noélie Maillard, a) Rameshwar U. Kadam, a) David Kalbermatter, a) Marcel Meury,b) Malcolm G. P. Page, c) Dimitrios Fotiadis, b) Tamis Darbre and Jean-Louis Reymond a) * a) Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Berne, Freiestrasse 3, CH-3012 Berne Fax: + 41 31 631 80 57; Tel: +41 31 631 43 25, e-mail: [email protected] b) Institute of Biochemistry and Molecular Medicine, University of Berne, Bühlstrasse 28, 3012 Berne, Switzerland c) Basilea Pharmaceutica International Ltd. Table of Contents MATERIAL AND REAGENTS ....................................................................................................................................... 2 COMBINATORIAL LIBRARY ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Library synthesis ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Bead diffusion assay............................................................................................................................................ 3 Sequence determination...................................................................................................................................... -

Security Systems Services World Report

Security Systems Services World Report established in 1974, and a brand since 1981. www.datagroup.org Security Systems Services World Report Database Ref: 56162 This database is updated monthly. Security Systems Services World Report SECURITY SYSTEMS SERVICES WORLD REPORT The Security systems services Report has the following information. The base report has 59 chapters, plus the Excel spreadsheets & Access databases specified. This research provides World Data on Security systems services. The report is available in several Editions and Parts and the contents and cost of each part is shown below. The Client can choose the Edition required; and subsequently any Parts that are required from the After-Sales Service. Contents Description ....................................................................................................................................... 5 REPORT EDITIONS ........................................................................................................................... 6 World Report ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Regional Report ................................................................................................................................... 6 Country Report .................................................................................................................................... 6 Town & Country Report ...................................................................................................................... -

Zirconium Compounds 224 200 Countries

Zirconium Compounds Markets 224 Companies 200 Countries Worldwide Since 1983 www.datagroup.org Zirconium Compounds Zirconium Compounds Zirconium Compounds The Market report is an extract of the main database and provides a number of limited datasets for each of the countries covered. For users needing more information, detailed data on Zirconium Compounds is available in several Editions and Database versions. Users can order (at a discount) any other Editions, or the full Database version, as required from the After-Sales Service or from any Dealer. This research provides Market data for Zirconium compounds. Contents Market Report ................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Market Data in US$ .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Report Description ..................................................................................................................................................... 5 Contents ..................................................................................................................................................................... 9 Countries Covered ................................................................................................................................................... 12 Market Notes & Definitions ..................................................................................................................................... -

Package 'Boral'

Package ‘boral’ March 12, 2021 Title Bayesian Ordination and Regression AnaLysis Version 2.0 Date 2021-04-01 Author Francis K.C. Hui [aut, cre], Wade Blanchard [aut] Maintainer Francis K.C. Hui <[email protected]> Description Bayesian approaches for analyzing multivariate data in ecology. Estimation is per- formed using Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods via Three. JAGS types of mod- els may be fitted: 1) With explanatory variables only, boral fits independent column General- ized Linear Models (GLMs) to each column of the response matrix; 2) With latent vari- ables only, boral fits a purely latent variable model for model-based unconstrained ordina- tion; 3) With explanatory and latent variables, boral fits correlated column GLMs with la- tent variables to account for any residual correlation between the columns of the response matrix. License GPL-2 Depends coda Imports abind, corpcor, fishMod, graphics, grDevices, lifecycle, MASS, mvtnorm, R2jags, reshape2, stats Suggests mvabund (>= 4.0.1), corrplot NeedsCompilation no R topics documented: boral-package . .2 about.distributions . .3 about.lvs . .6 about.ranefs . .8 about.ssvs . 10 about.traits . 14 boral . 17 calc.condlogLik . 33 calc.logLik.lv0 . 37 calc.marglogLik . 40 1 2 boral-package calc.varpart . 44 coefsplot . 48 create.life . 51 ds.residuals . 59 fitted.boral . 61 get.dic . 63 get.enviro.cor . 64 get.hpdintervals . 66 get.mcmcsamples . 70 get.measures . 71 get.more.measures . 75 get.residual.cor . 79 lvsplot . 82 make.jagsboralmodel . 85 make.jagsboralnullmodel . 90 plot.boral . 95 predict.boral . 97 ranefsplot . 103 summary.boral . 105 tidyboral . 106 Index 110 boral-package Bayesian Ordination and Regression AnaLysis (boral) Description Bayesian approaches for analyzing multivariate data in ecology. -

Boral’ January 2, 2017 Title Bayesian Ordination and Regression Analysis Version 1.2 Date 2017-01-10 Author Francis K.C

Package ‘boral’ January 2, 2017 Title Bayesian Ordination and Regression AnaLysis Version 1.2 Date 2017-01-10 Author Francis K.C. Hui Maintainer Francis Hui <[email protected]> Description Bayesian approaches for analyzing multivariate data in ecology. Estimation is per- formed using Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods via JAGS. Three types of mod- els may be fitted: 1) With explanatory variables only, boral fits independent col- umn GLMs to each column of the response matrix; 2) With latent variables only, bo- ral fits a purely latent variable model for model-based unconstrained ordination; 3) With explana- tory and latent variables, boral fits correlated column GLMs with latent variables to ac- count for any residual correlation between the columns of the response matrix. License GPL-2 Depends coda Imports R2jags, mvtnorm, fishMod, MASS, stats, graphics, grDevices, abind Suggests mvabund (>= 3.8.4), corrplot NeedsCompilation no Repository CRAN Date/Publication 2017-01-02 22:22:18 R topics documented: boral-package . .2 about.distributions . .3 about.ssvs . .5 about.traits . .8 boral . 10 calc.condlogLik . 23 calc.logLik.lv0 . 26 calc.marglogLik . 29 coefsplot . 33 1 2 boral-package create.life . 35 ds.residuals . 40 fitted.boral . 42 get.dic . 43 get.enviro.cor . 45 get.hpdintervals . 46 get.measures . 49 get.more.measures . 52 get.residual.cor . 56 lvsplot . 58 make.jagsboralmodel . 61 make.jagsboralnullmodel . 65 plot.boral . 70 summary.boral . 72 Index 74 boral-package Bayesian Ordination and Regression AnaLysis (boral) Description boral is a package offering Bayesian model-based approaches for analyzing multivariate data in ecology. Estimation is performed using Bayesian/Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods via JAGS (Plummer, 2003). -

Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

University of Bath PHD Self-assembled peptide hydrogels Johnson, Eleanor Award date: 2011 Awarding institution: University of Bath Link to publication Alternative formats If you require this document in an alternative format, please contact: [email protected] General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 09. Oct. 2021 SELF-ASSEMBLED PEPTIDE HYDROGELS Eleanor Johnson A Thesis Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Bath Department of Chemistry December 2011 COPYRIGHT Attention is drawn to the fact that copyright of this thesis rests with the author. A copy of this thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that they must not copy it or use material from it except as permitted by law or with the consent of the author. -

Topspin User Manual

TOPSPIN Users Guide Copyright (C) 2005 by Bruker BioSpin GmbH All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval sys- tem, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means without the prior consent of the publisher. Part Number H9469SA1 V2/January 31st 2005 Product names used are trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective holders. INDEX DONE INDEX Bruker software support is available via phone, fax, e-mail, Internet, or ISDN. Please contact your local office, or directly: Address: Bruker BioSpin GmbH Software Department Silberstreifen D-76287 Rheinstetten Germany Phone: +49 (721) 5161 455 Fax: +49 (721) 5161 943 E-mail: [email protected] FTP: ftp.bruker.de / ftp.bruker.com WWW: www.bruker-biospin.de / www.bruker-biospin.com Chapter 1 Getting Started . 15 1.1 Document Conventions . 15 Font Conventions . 15 File/directory Conventions . 15 User Action Conventions . 15 1.2 TOPSPIN Overview . 16 Functionality . 16 Available Documentation . 17 1.3 TOPSPIN license . 17 1.4 Startup TOPSPIN . 18 1.5 Configuration . 18 1.6 How to Display Spectra . 19 How to Open Data from the Menu . 19 How to Open Data from the Browser . 20 How to Define Alias Names for Data . 20 How to Open Data in Other Ways . 20 1.7 How to Display Peaks, Integrals, ... together with the Spectrum . 20 1.8 How to Display Projections/1D Spectra with 2D Spectra . 21 1.9 How to Superimpose Spectra in Multiple Display . 21 1.10 How to Print or Export the Contents of a Data Window . -

Porcelain & Ceramic Products (B2B Procurement)

Porcelain & Ceramic Products (B2B Procurement) Purchasing World Report Since 1979 www.datagroup.org Porcelain & Ceramic Products (B2B Procurement) Porcelain & Ceramic Products (B2B Procurement) 2 B B Purchasing World Report Porcelain & Ceramic Products (B2B Procurement) The Purchasing World Report is an extract of the main database and provides a number of limited datasets for each of the countries covered. For users needing more information, detailed data on Porcelain & Ceramic Products (B2B Procurement) is available in several Editions and Database versions. Users can order (at a discount) any other Editions, or the Database versions, as required from the After-Sales Service or from any Dealer. This research provides data the Buying of Materials, Products and Services used for Porcelain & Ceramic Products. Contents B2B Purchasing World Report ................................................................................................................................... 2 B2B Purchasing World Report Specifications ............................................................................................................ 4 Materials, Products and Services Purchased : US$ ........................................................................................... 4 Report Description .................................................................................................................................................. 6 Tables .................................................................................................................................................................... -

Selected Physiological Characteristics of Elite Rowers Measured in the Laboratory and Field and Their Relationship with Performance

SELECTED PHYSIOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF ELITE ROWERS MEASURED IN THE LABORATORY AND FIELD AND THEIR RELATIONSHIP WITH PERFORMANCE by GILES D. WARRINGTON A thesis submitted to the University of Surrey for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Robens Institute University of Surrey Guildford Surrey GU2 5XH England July 1998 ProQuest Number: 27750273 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted. in the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest27750273 Published by ProQuest LLC(2019). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. Ail Rights Reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106 - 1346 ABSTRACT In the present study, a number of physiological variables were measured on members of the Great Britain heavyweight rowing squad in the laboratory, field and also during altitude training. The main purposes of the study were to determine which of these physiological variables were important determinants of success in rowing and to evaluate the effects of a specific phase of training on these variables. Additionally, the study sought to assess the effectiveness of different modes of training by monitoring the physiological responses and adaptations to a period of altitude training and evaluating their impact on aerobic work capacity on return to sea level. -

Ophthalmic Fronts & Temples

Ophthalmic Fronts & Temples PDF Express Edition Available from: Phone: +44 208 123 2220 or +1 732 587 5005 [email protected] Sales Manager: Alison Smith on +44 208 123 2220 [email protected] Ophthalmic Fronts & Temples Ophthalmic Fronts & Temples Ophthalmic Fronts & Temples The PDF report is an extract of the main database and provides a number of limited datasets for each of the countries covered. For users needing more information, detailed data on Ophthalmic Fronts & Temples is available in several geographic Editions and Database versions. Users can order any other Editions, or the full Database version, as required from the After-Sales Service or from any NIN Dealer at a discount. This research provides data on Ophthalmic Fronts & Temples. Contents Express Edition .......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Products & Markets .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Report Description ..................................................................................................................................................... 5 Tables ........................................................................................................................................................................ 5 Countries Covered .................................................................................................................................................. -

(Microsoft Powerpoint

Acil T ıp’ta İstatistik Sunum Plan ı IV. Acil Tıp Asistan Sempozyumu 19-21 Haziran 2009 Biyoistatistik nedir Sa ğlık alan ında biyoistatistik Acil T ıp’ta biyoistatistik Meral Leman Almac ıoğlu İstatistik yaz ılım programlar ı Uluda ğ Üniversitesi T ıp Fakültesi Acil T ıp AD Bursa Biyoistatistik Nedir Biyoistatistik Niçin Gereklidir 1. Biyolojik, laboratuar ve klinik verilerdeki yayg ınl ık ı ğ ı Biyoistatistik; t p ve sa l k bilimleri 2. Verilerin anla şı lmas ı alanlar ında veri toplanmas ı, özetleme, 3. Yorumlanmas ı analiz ve de ğerlendirmede istatistiksel 4. Tıp literatürünün kriti ğinin yap ılmas ı yöntemleri kullanan bilim dal ı 5. Ara ştırmalar ın planlanmas ı, gerçekle ştirilmesi, analiz ve yorumlanmas ı Biyoistatistiksel teknikler kullan ılmadan gerçekle ştirilen ara ştırmalar bilimsel ara ştırmalar de ğildir Acil’de İstatistik Sa ğlık istatistikleri sa ğlık çal ış anlar ının verdi ği bilgilerden derlenmekte Acil Servis’in hasta yo ğunlu ğunun y ıl-ay-gün-saat baz ında de ğerlendirilmesi bu veriler bir ülkede sa ğlık hizmetlerinin planlanmas ı Çal ış ma saatlerinin ve çal ış mas ı gereken ki şi say ısının ve de ğerlendirmesinde kullan ılmakta planlanmas ı Gerekli malzeme, yatak say ısı, ilaç vb. planlanmas ı Verilen hizmetin kalitesinin ölçülmesi İyi bir biyoistatistik eğitim alan sa ğlık personelinin o Eğitimin kalitesinin ölçülmesi ülkenin sa ğlık informasyon sistemlerine güvenilir Pandemi ve epidemilerin tespiti katk ılarda bulunmas ı beklenir Yeni çal ış malar, tezler … İstatistik Yaz ılım Programlar ı İİİstatistiksel -

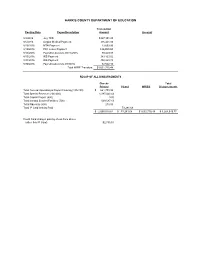

HCDE Procurement Card Report August Statement

HARRIS COUNTY DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Transaction Posting Date Payee/Description Amount Account 8/3/2016 July TRS $327,391.25 8/5/2016 August Medical Payment 316,441.00 8/10/2016 MTN Payment 13,600.00 8/10/2016 PFC Lease Payment 126,899.50 8/15/2016 Payroll Deductions 08/15/2016 30,449.03 8/15/2016 IRS Payment 383,163.82 8/31/2016 IRS Payment 402,228.78 8/30/2016 Payroll Deductions 08/30/16 32,542.10 Total WIRE Transfers: $1,632,715.48 RECAP OF ALL DISBURSEMENTS Checks Total Printed PCard WIRES Disbursements Total General Operating & Payroll Clearing (100-199) $ 661,708.04 Total Special Revenue (200-400) 1,387,043.44 Total Capital Project (600) 0.00 Total Internal Service/Facilities (700) 509,587.13 Total Fiduciary (800) 210.00 Total P Card Activity Paid 73,281.68 $ 2,558,548.61 $ 73,281.68 $1,632,715.48 $ 4,264,545.77 Credit Card charges paid by check from above (other than P Card) $2,735.01 Harris County Department of Education Vendors with total aggregate payments of $50,000 or more in Fiscal Year 2016 as of August 31, 2016 Vendor Vendor number Contract Type Sum of payments ACCUDATA SYSTEMS INC 86793 Service Agreement 64,031.25 ALDINE INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT 10960 Interlocal 490,773.00 ALIEF INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT 84484 Interlocal 591,458.03 AMBONARE INCORPORATED 87061 JOB # 15/044MP-01 60,000.00 ARTHUR J GALLAGHER RISK MANAGEMENT 87377 Workers Comp. 242,564.00 BUTLER BUSINESS PRODUCTS 17320 JOB # 14/010DG 268,752.00 CBS PERSONNEL SERVICES LLC 61915 JOB #13/001DG 192,481.11 CDW GOVERNMENT INC 18165 JOB #13/068DG 274,013.44