Japan Studies Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Japanese Immigration History

CULTURAL ANALYSIS OF THE EARLY JAPANESE IMMIGRATION TO THE UNITED STATES DURING MEIJI TO TAISHO ERA (1868–1926) By HOSOK O Bachelor of Arts in History Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado 2000 Master of Arts in History University of Central Oklahoma Edmond, Oklahoma 2002 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December, 2010 © 2010, Hosok O ii CULTURAL ANALYSIS OF THE EARLY JAPANESE IMMIGRATION TO THE UNITED STATES DURING MEIJI TO TAISHO ERA (1868–1926) Dissertation Approved: Dr. Ronald A. Petrin Dissertation Adviser Dr. Michael F. Logan Dr. Yonglin Jiang Dr. R. Michael Bracy Dr. Jean Van Delinder Dr. Mark E. Payton Dean of the Graduate College iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For the completion of my dissertation, I would like to express my earnest appreciation to my advisor and mentor, Dr. Ronald A. Petrin for his dedicated supervision, encouragement, and great friendship. I would have been next to impossible to write this dissertation without Dr. Petrin’s continuous support and intellectual guidance. My sincere appreciation extends to my other committee members Dr. Michael Bracy, Dr. Michael F. Logan, and Dr. Yonglin Jiang, whose intelligent guidance, wholehearted encouragement, and friendship are invaluable. I also would like to make a special reference to Dr. Jean Van Delinder from the Department of Sociology who gave me inspiration for the immigration study. Furthermore, I would like to give my sincere appreciation to Dr. Xiaobing Li for his thorough assistance, encouragement, and friendship since the day I started working on my MA degree to the completion of my doctoral dissertation. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Exponent of Breath: The Role of Foreign Evangelical Organizations in Combating Japan's Tuberculosis Epidemic of the Early 20th Century Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/32d241sf Author Perelman, Elisheva Avital Publication Date 2011 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Exponent of Breath: The Role of Foreign Evangelical Organizations in Combating Japan’s Tuberculosis Epidemic of the Early 20th Century By Elisheva Avital Perelman A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Andrew E. Barshay, Chair Professor John Lesch Professor Alan Tansman Fall 2011 © Copyright by Elisheva Avital Perelman 2011 All Rights Reserved Abstract The Role of Foreign Evangelical Organizations in Combating Japan’s Tuberculosis Epidemic of the Early 20th Century By Elisheva Avital Perelman Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Andrew E. Barshay, Chair Tuberculosis existed in Japan long before the arrival of the first medical missionaries, and it would survive them all. Still, the epidemic during the period from 1890 until the 1920s proved salient because of the questions it answered. This dissertation analyzes how, through the actions of the government, scientists, foreign evangelical leaders, and the tubercular themselves, a nation defined itself and its obligations to its subjects, and how foreign evangelical organizations, including the Young Men’s Christian Association (the Y.M.C.A.) and The Salvation Army, sought to utilize, as much as to assist, those in their care. -

Joseph Heco and the Origin of Japanese Journalism*

Journalism and Mass Communication, Mar.-Apr. 2020, Vol. 10, No. 2, 89-101 doi: 10.17265/2160-6579/2020.02.003 D DAVID PUBLISHING Joseph Heco and the Origin of Japanese Journalism* WANG Hai, YU Qian, LIANG Wei-ping Guangdong University of Foreign Studies, Guangzhou, China Joseph Heco, with the original Japanese name of Hamada Hikozo, played an active role in the diplomatic, economic, trade, and cultural interactions between the United States and Japan in the 1850s and 1860s. Being rescued from a shipwreck by an American freighter and taken to San Francisco in the 1850s, Heco had the chance to experience the advanced industrial civilization. After returning to Japan, he followed the example of the U.S. newspapers to start the first Japanese newspaper Kaigai Shimbun (Overseas News), introducing Western ideas into Japan and enabling Japanese people under the rule of the Edo bakufu/shogunate to learn about the great changes taking place outside the island. In the light of the historical background of the United States forcing Japan to open up, this paper expounds on Joseph Heco’s life experience and Kaigai Shimbun, the newspaper he founded, aiming to explain how Heco, as the “father of Japanese journalism”, promoted the development of Japanese newspaper industry. Keywords: Joseph Heco (Hamada Hikozo), Kaigai Shimbun, origin of Japanese journalism Early Japanese newspapers originated from the “kawaraban” (瓦版) at the beginning of the 17th century. In 1615, this embryonic form of newspapers first appeared in the streets of Osaka. This single-sided leaflet-like thing was printed irregularly and was made by printing on paper with tiles which was carved with pictures and words and then fired and shaped. -

Acta Asiatica Varsoviensia No. 27 Acta Asiatica Varsoviensia

ACTA ASIATICA VARSOVIENSIA NO. 27 ACTA ASIATICA VARSOVIENSIA Editor-in-Chief Board of Advisory Editors MARIA ROMAN S£AWIÑSKI NGUYEN QUANG THUAN KENNETH OLENIK Subject Editor ABDULRAHMAN AL-SALIMI OLGA BARBASIEWICZ JOLANTA SIERAKOWSKA-DYNDO BOGDAN SK£ADANEK Statistical Editor LEE MING-HUEI MARTA LUTY-MICHALAK ZHANG HAIPENG Institute of Mediterranean and Oriental Cultures Polish Academy of Sciences ACTA ASIATICA VARSOVIENSIA NO. 27 ASKON Publishers Warsaw 2014 Secretary Nicolas Levi English Text Consultant James Todd © Copyright by Institute of Mediterranean and Oriental Cultures, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw 2014 Printed in Poland This edition prepared, set and published by Wydawnictwo Naukowe ASKON Sp. z o.o. Stawki 3/1, 00193 Warszawa tel./fax: (+48) 22 635 99 37 www.askon.waw.pl [email protected] PL ISSN 08606102 ISBN 978837452080–5 ACTA ASIATICA VARSOVIENSIA is abstracted in The Central European Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, Index Copernicus To the memory of Professor Karin Tomala Whom we lost for ever Contents ARTICLES OLGA BARBASIEWICZ, The Cooperation of Jacob Schiff and Takahashi Korekiyo Regarding the Financial Support for the War with Russia (19041905). Analysis of Schiff and Takahashis Private Correspondence and Diaries ............................................................................ 9 KAROLINA BROMA-SMENDA, Enjo-kôsai (compensated dating) in Contemporary Japanese Society as Seen through the Lens of the Play Call Me Komachi ....................................................................... -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-72474-6 — an Introduction to Japanese Society Yoshio Sugimoto Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-72474-6 — An Introduction to Japanese Society Yoshio Sugimoto Index More Information Index Abe, Shinz¯o,236, 303, 312 alternative culture, 285 abilities, of employees, 116–17 characteristics, 287 abortion, 186–8 communes and the natural economy, 299–300 academic world system, 52–3 Cool Japan as, 311 achieved status, 73–4, 81 countercultural events and performances, 298–9 Act on Land and Building Leases (1991), 122 historical examples, 297 Act on Promotion of Women’s Participation local resident–volunteer support movements as, and Advancement in the Workplace (2016), 325 182 mini-communication media and online papers, activism, see resident movements; social 297–8 movements nature of, 297 administrative guidance (gyosei¯ shido¯), 232, 235–6, social formations producing, 286 338 amae (active dependency), 29, 43, 51 administrative systems amakudari (descending from heaven), 232–5, 251 during Heian period, 9 Amaterasu Ōmikami, 6–7, 267 during Kamakura period, 10 ambiguity, manipulation of, 337–8 during Yamato period, 7 Ame no Uzume, 6 adoption, 196 Ampo struggle, 318, 321 AEON, 110 ancestor worship, 266, 281, 295 aging society, 47–8 animators, working conditions, 307 declining birth rate and, 86–7 anime, 27–8, 46–7, 302, 311 life expectancy in, 84–6 animism, 203, 266–7 rise in volunteering and, 323 annual leave, 120 woman’s role as caregiver in, 181 anomie (normlessness), 48 Agon-shu¯ (Agon sect), 273 anti-development protests, 324–5 agricultural cooperatives, 326 anti-nuclear demonstrations, 92, 317–21 -

Battle of Okinawa 1 Battle of Okinawa

Battle of Okinawa 1 Battle of Okinawa Battle of Okinawa Part of World War II, the Pacific War A U.S. Marine from the 2nd Battalion, 1st Marines on Wana Ridge provides covering fire with his Thompson submachine gun, 18 May 1945. Date 1 April – 22 June 1945 Location Okinawa, Japan [1] [1] 26°30′N 128°00′E Coordinates: 26°30′N 128°00′E Result Allied victory, Okinawa occupied by U.S. until 1972 Belligerents United States Empire of Japan United Kingdom Canada Australia New Zealand Commanders and leaders Simon B. Buckner, Jr. † Mitsuru Ushijima † Roy Geiger Isamu Chō † Joseph Stilwell Minoru Ota † Chester W. Nimitz Keizō Komura Raymond A. Spruance Sir Bernard Rawlings Philip Vian Bruce Fraser Strength 183,000 (initial assault force only) ~120,000, including 40,000 impressed Okinawans Casualties and losses More than 12,000 killed More than 110,000 killed More than 38,000 wounded More than 7,000 captured 40,000–150,000 civilians killed The Battle of Okinawa, codenamed Operation Iceberg, was fought on the Ryukyu Islands of Okinawa and was the largest amphibious assault in the Pacific War of World War II. The 82-day-long battle lasted from early April until mid-June 1945. After a long campaign of island hopping, the Allies were approaching Japan, and planned to use Okinawa, a large island only 340 mi (550 km) away from mainland Japan, as a base for air operations on the planned Battle of Okinawa 2 invasion of Japanese mainland (coded Operation Downfall). Four divisions of the U.S. -

The Book of Abstracts

BOOK OF ABSTRACTS Correct as of 6th September 2019 1 PANELS A Panel 53 Sourcing Korea in Korean History: Historical Sources and the Production of Knowledge of Korea’s Pasts This panel investigates one of the fundamental challenges facing historians: that of the limits and possibilities of historical sources. Korean history has flourished as an academic field in recent decades, alongside a dramatic growth in archives and databases of primary sources. This expansion of both primary and secondary sources on Korean history provides an opportune moment to reflect on how historical knowledge of Korea has developed in tandem with the availability of a wider variety of primary sources. While appreciating the general trends in the production of Korean history, this panel poses questions over how newly available primary sources are changing historical narratives of Korea. In particular, we complicate pre-conceived notions of Korean history, as developments in both local and transnational history challenge existing understandings of “Korean” history. John S. Lee discusses differences between bureaucratic and local sources, to argue for a pluralist perspective on Chosŏn environmental knowledge that reflects the production of sources by different interest groups. Holly Stephens discusses conflicting accounts of the colonial period and the challenge posed by hanmun diaries to standard histories of Korea’s colonization. In particular, she questions the politicization of everyday life that emerges from distinct sets of sources. Finally, Luis Botella examines alternative presentations of archaeological knowledge in postwar South Korea that highlight the influence of American, Soviet, colonial, and post-colonial frames of knowledge in defining formative narratives of Korean history. -

The Legalization of Hinomaru and Kimigayo As Japan's National Flag

The legalization of Hinomaru and Kimigayo as Japan's national flag and anthem and its connections to the political campaign of "healthy nationalism and internationalism" Marit Bruaset Institutt for østeuropeiske og orientalske studier, Universitetet i Oslo Vår 2003 Introduction The main focus of this thesis is the legalization of Hinomaru and Kimigayo as the national flag and anthem of Japan in 1999 and its connections to what seems to be an atypical Japanese form of postwar nationalism. In the 1980s a campaign headed by among others Prime Minister Nakasone was promoted to increase the pride of the Japanese in their nation and to achieve a “transformation of national consciousness”.1 Its supporters tended to use the term “healthy nationalism and internationalism”. When discussing the legalization of Hinomaru and Kimigayo as the national flag and anthem of Japan, it is necessary to look into the nationalism that became evident in the 1980s and see to what extent the legalization is connected with it. Furthermore we must discuss whether the legalization would have been possible without the emergence of so- called “healthy nationalism and internationalism”. Thus it is first necessary to discuss and try to clarify the confusing terms of “healthy nationalism and patriotism”. Secondly, we must look into why and how the so-called “healthy nationalism and internationalism” occurred and address the question of why its occurrence was controversial. The field of education seems to be the area of Japanese society where the controversy regarding its occurrence was strongest. The Ministry of Education, Monbushō, and the Japan Teachers' Union, Nihon Kyōshokuin Kumiai (hereafter Nikkyōso), were the main opponents struggling over the issue of Hinomaru, and especially Kimigayo, due to its lyrics praising the emperor. -

1. the Rising Sun Flag As Part of Japanese Culture the Design of the Rising Sun Flag Symbolizes the Sun As the Japanese National Flag Does

1. The Rising Sun Flag As Part Of Japanese Culture The design of the Rising Sun Flag symbolizes the sun as the Japanese national flag does. This design has been widely used in Japan for a long time. Today, the design of the Rising Sun Flag is seen in numerous scenes in daily life of Japan, such as in fishermen’s banners hoisted to signify large catch of fish, flags to celebrate childbirth, and in flags for seasonal festivities. Japanese culture and rising sun flags Daily life and rising sun flags Priest Kiyomori, an old Kabuki story , by The return to Ukedo port (2017) of People celebrating the opening of Ginko Adachi, 1885 An ukiyoe print , Lucky gods Visit fishing boats that had evacuated due to the Hokkaido Shinkansen with big Enoshima Palace, by Yoshiiku the Great East Japan Earthquake fishing flags, 2016 Ochiai, 1869 ©Kyodo News Images ©Kyodo News Images Reference ●Press Conference by the Chief Cabinet Secretary KATO, May 18, 2021(AM) (excerpt) ・・・・・As you all know, the design of the Rising Sun Flag models the shape of the sun like the national flag of Japan and is widely used throughout Japan, such as good catch flags used by fishermen and celebratory flags for childbirth and seasonal festivities. Claims that the flag is an expression of political or discriminatory assertions are false. The Government of Japan has explained, and will continue to explain at every opportunity its view that the display of the Rising Sun Flag is not political promotion, to the international community including the Republic of Korea. -

2Nd Global Conference Music and Nationalism National Anthem Controversy and the ‘Spirit of Language’ Myth in Japan

2nd Global Conference Music and Nationalism National Anthem Controversy and the ‘Spirit of Language’ Myth in Japan Naoko Hosokawa Max Weber Postdoctoral Fellow European University Institute, Florence Email address: [email protected] Abstract This paper will discuss the relationship between the national anthem controversy and the myth of the spirit of language in Japan. Since the end of the Pacific War, the national anthem of Japan, Kimigayo (His Imperial Majesty's Reign), has caused exceptionally fierce controversies in Japan. Those who support the song claim that it is a traditional national anthem sung since the nineteenth century with the lyrics based on a classical waka poem written in the tenth century, while those opposed to it see the lyrics as problematic for their imperialist ideology and association with negative memories of the war. While it is clear that the controversies are mainly based on the political interpretation of the lyrics, the paper will shed light on the myth of the spirit of language, known as kotodama, as a possible explanation for the uncommon intensity of the controversy. The main idea of the myth is that words, pronounced in a certain manner have an impact on reality. Based on this premise, the kotodama myth has been reinterpreted and incorporated into Japanese social and political discourses throughout its history. Placing a particular focus on links between music and the kotodama myth, the paper will suggest that part of the national anthem controversy in Japan can be explained by reference to the discursive use of the myth. Keywords: National anthem, nationalism, Japan, language, myth 1. -

JAPANIN OUTOUDEN TAKANA Japanilaisen Populaarikulttuurin Käsitteleminen Länsimaisessa Mediassa

Petteri Uusitalo JAPANIN OUTOUDEN TAKANA Japanilaisen populaarikulttuurin käsitteleminen länsimaisessa mediassa JAPANIN OUTOUDEN TAKANA Japanilaisen populaarikulttuurin käsitteleminen länsimaisessa mediassa Petteri Uusitalo Opinnäytetyö Kevät 2019 Viestinnän tutkinto-ohjelma Oulun ammattikorkeakoulu TIIVISTELMÄ Oulun ammattikorkeakoulu Viestinnän tutkinto-ohjelma, journalismin suuntautumisvaihtoehto Tekijä: Petteri Uusitalo Opinnäytetyön nimi: Japanin outouden takana – Japanilaisen populaarikulttuurin käsitteleminen länsimaisessa mediassa Työn ohjaaja: Teemu Palokangas Työn valmistumislukukausi ja -vuosi: Kevät 2019 Sivumäärä: 79 + 13 Japanilaisen populaarikulttuurin merkityksellisyys maailmanlaajuisella viihdekentällä on kasvanut viime vuosikymmenten aikana. Sen näkyvimmät ilmenemismuodot ovat japanilainen animaatio ja sarjakuva eli anime ja manga. Tässä tutkielmassa avaan sitä, miten länsimaisessa yhteiskunnassa Japaniin liittyy erityinen asenneilmapiiri, jonka mukaan Japani on humoristinen ja eriskummallinen maa, ja miten tämä asenneilmapiiri vaikuttaa japanilaiseen populaarikulttuuriin suhtautumiseen yleismediassa. Japanilaiseen populaarikulttuuriin keskittyvässä ja sen harrastajille suunnatussa erikoismediassa lähestymistapa on kuitenkin toinen, kuten tutkielman tutkimusosa osoittaa. Anime-lehti on vuonna 2005 perustettu suomalainen japanilaiseen populaarikulttuuriin keskittyvä aikakauslehti. Tutkimusosassa tarkastelen lehdessä esiintyviä näkemyksiä, lähestymistapoja ja asenteita Japanin kulttuuria ja populaarikulttuuria kohtaan. -

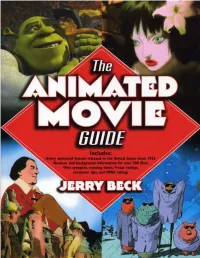

The Animated Movie Guide

THE ANIMATED MOVIE GUIDE Jerry Beck Contributing Writers Martin Goodman Andrew Leal W. R. Miller Fred Patten An A Cappella Book Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Beck, Jerry. The animated movie guide / Jerry Beck.— 1st ed. p. cm. “An A Cappella book.” Includes index. ISBN 1-55652-591-5 1. Animated films—Catalogs. I. Title. NC1765.B367 2005 016.79143’75—dc22 2005008629 Front cover design: Leslie Cabarga Interior design: Rattray Design All images courtesy of Cartoon Research Inc. Front cover images (clockwise from top left): Photograph from the motion picture Shrek ™ & © 2001 DreamWorks L.L.C. and PDI, reprinted with permission by DreamWorks Animation; Photograph from the motion picture Ghost in the Shell 2 ™ & © 2004 DreamWorks L.L.C. and PDI, reprinted with permission by DreamWorks Animation; Mutant Aliens © Bill Plympton; Gulliver’s Travels. Back cover images (left to right): Johnny the Giant Killer, Gulliver’s Travels, The Snow Queen © 2005 by Jerry Beck All rights reserved First edition Published by A Cappella Books An Imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 1-55652-591-5 Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 For Marea Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction ix About the Author and Contributors’ Biographies xiii Chronological List of Animated Features xv Alphabetical Entries 1 Appendix 1: Limited Release Animated Features 325 Appendix 2: Top 60 Animated Features Never Theatrically Released in the United States 327 Appendix 3: Top 20 Live-Action Films Featuring Great Animation 333 Index 335 Acknowledgments his book would not be as complete, as accurate, or as fun without the help of my ded- icated friends and enthusiastic colleagues.