Gérard Depardieu, Innocent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum Rivette: Texts and Interviews (editor, 1977) Orson Welles: A Critical View, by André Bazin (editor and translator, 1978) Moving Places: A Life in the Movies (1980) Film: The Front Line 1983 (1983) Midnight Movies (with J. Hoberman, 1983) Greed (1991) This Is Orson Welles, by Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich (editor, 1992) Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (1995) Movies as Politics (1997) Another Kind of Independence: Joe Dante and the Roger Corman Class of 1970 (coedited with Bill Krohn, 1999) Dead Man (2000) Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (2000) Abbas Kiarostami (with Mehrmax Saeed-Vafa, 2003) Movie Mutations: The Changing Face of World Cinephilia (coedited with Adrian Martin, 2003) Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons (2004) Discovering Orson Welles (2007) The Unquiet American: Trangressive Comedies from the U.S. (2009) Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Film Culture in Transition Jonathan Rosenbaum the university of chicago press | chicago and london Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote for many periodicals (including the Village Voice, Sight and Sound, Film Quarterly, and Film Comment) before becoming principal fi lm critic for the Chicago Reader in 1987. Since his retirement from that position in March 2008, he has maintained his own Web site and continued to write for both print and online publications. His many books include four major collections of essays: Placing Movies (California 1995), Movies as Politics (California 1997), Movie Wars (a cappella 2000), and Essential Cinema (Johns Hopkins 2004). The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2010 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. -

The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema to Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

Robert Phillip Kolker The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/8 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Robert Kolker is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Maryland and Lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. His works include A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg Altman; Bernardo Bertolucci; Wim Wenders (with Peter Beicken); Film, Form and Culture; Media Studies: An Introduction; editor of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey: New Essays and The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies. http://www.virginia.edu/mediastudies/people/adjunct.html Robert Phillip Kolker THE ALTERING EYE Contemporary International Cinema Revised edition with a new preface and an updated bibliography Cambridge 2009 Published by 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com First edition published in 1983 by Oxford University Press. © 2009 Robert Phillip Kolker Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Cre- ative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 2.0 UK: England & Wales Licence. This licence allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author -

LE TEMPS DES NABABS Une Série Documentaire De Florence Strauss Les Films D’Ici Et Le Pacte Présentent

COMMENT PRODUISAIT-ON AVANT LA TÉLÉVISION ? LE TEMPS DES NABABS Une série documentaire de Florence Strauss Les Films d’Ici et Le Pacte présentent COMMENT PRODUISAIT-ON AVANT LA TÉLÉVISION ? LE TEMPS DES NABABS Une série documentaire de Florence Strauss 8 x 52min – France – 2019 – Flat - stéréo À PARTIR DU 12 OCTOBRE SUR CINÉ + CLASSIC RELATIONS PRESSE Marie Queysanne Assistée de Fatiha Zeroual Tél. : 01 42 77 03 63 [email protected] [email protected] SYNOPSIS LISTE DES ÉPISODES Pierre Braunberger, Anatole Dauman, Robert Dorfmann, les frères ÉPISODE 1 : LES ROMANESQUES Hakim, Mag Bodard, Alain Poiré, Pierre Cottrell, Albina du Boisrouvray, Robert et Raymond Hakim - Casque d’Or Jacques Perrin, Jean-Pierre Rassam et bien d’autres… Ils ont toujours André Paulvé - La Belle et la Bête oeuvré dans l’ombre et sont restés inconnus du grand public. Pourtant Alexandre Mnouchkine et Georges Dancigers - Fanfan La Tulipe ils ont produit des films que nous connaissons tous, deLa Grande Henri Deutschmeister - French Cancan vadrouille à La Grande bouffe, de Fanfan la tulipe à La Maman et la putain, de Casque d’or à La Belle et la bête. ÉPISODE 2 : LES TENACES Robert Dorfmann - Jeux interdits Autodidactes, passionnés, joueurs, ils ont financé le cinéma avec une Pierre Braunberger - Une Histoire d’eau inventivité exceptionnelle à une époque où ni télévisions, ni soficas ou Anatole Dauman - Nuit et brouillard autres n’existaient. Partis de rien, ils pouvaient tout gagner… ou bien tout perdre. Ce sont des personnages hauts en couleur, au parcours ÉPISODE 3 : LES AUDACIEUX souvent digne d’une fiction. -

Keeping Apuleius in the Picture a Dialogue Between Buñuel’S Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie and the Metamorphoses of Apuleius

Keeping Apuleius In The Picture A dialogue between Buñuel’s Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie and The Metamorphoses of Apuleius PAULA JAMES Open University UK Summary This article explores common motifs and narrative strategies which appear in the work of the second century CE Latin author, Apuleius, and the twentieth century Spanish film director Luis Buñuel. The use of narration to delay nutri- tion is a vital starting point for the comparative analysis. The focus of both these ‘texts’ makes them appropriate (though in some senses arbitrary) an- chors in what could eventually and fruitfully develop into a wide-ranging dis- cussion: i.e. the extent and significance of culinary metaphors in literary and cinematic narratives within a broad cultural spectrum. Uses and abuses of food and food consumption in both Apuleius and Buñuel intensify the bizarre at- mospheres of the stories. By means of diversionary and supernatural tales my chosen storytellers encourage their audiences to embrace credulity and to question the reality of appearances and consequently they subvert faith in the real world. In their hands magic and the surreal is an experimental strategy for producing a deeper insight into custom and society, not so much a message as an experience for the reader and the viewer, and one which shakes compla- cency about the solidity of social structures and physical forms. Introduction (trailer) Nihil impossibile arbitror sed utcumque fata decreverint, ita cuncta mor- talibus provenire. nam et mihi et tibi et cunctis hominibus multa usu ve- nire mira et paene infecta, quae tamen ignaro relata fidem perdant. (Apuleius’ hero, Lucius, Met.1.20) 186 PAULA JAMES ‘ “Well,” I said, “I consider nothing to be impossible. -

Buñuel by Dali

Luis Buñuel (Luis Buñuel Portolés, 22 February 1900, Calanda, Spain—29 July 1983, Mexico City, Mexico,cirrhosis of the liver) became a controversial and internationally-known filmmaker with his first film, the 17-minute Un Chien andalou 1929 (An Andalousian Dog), which he made with Salvador Dali. He wrote and directed 33 other films, most of them interesting, many of them considered masterpieces by critics and by fellow filmmakers. Some of them are : Cet obscur objet du désir 1977 (That Obscure Object of Desire), Le Charme discret de la bourgeoisie 1972 (The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie), Tristana 1970, La Voie lactée 1969 (The Milky Way), Belle de Jour 1967, Simón del desierto 1965 (Simon of the Desert), El Ángel Exterminador/Exterminating Angel 1962, 25 October 2005 XI:9 Viridiana 1961, Nazarín 1958, Subida al cielo DIARY OF A CHAMBERMAID/LE JOURNAL 1952 (Ascent to Heaven, Mexican Bus Ride), D'UNE FEMME DE CHAMBRE. (1964) 101 Los Olvidados 1950 (The Young and the minutes Damned), Las Hurdes 1932 (Land Without Bread ), and L’Âge d'or 1930 (Age of Gold). His Jeanne Moreau...Céléstine autobiography, My Last Sigh (Vintage, New Georges Géret...Joseph York) was published the year after his death. Daniel Ivernel...Captain Mauger Some critics say much of it is apocryphal, the Françoise Lugagne...Madame Monteil screenwriter Jean-Claude Carrière (who Muni...Marianne collaborated with Buñuel on six scripts), claims Jean Ozenne...Monsieur Rabour he wrote it based on things Buñel said. Michel Piccoli...Monsieur Monteil Whatever: it’s a terrific -

Hofstra University Film Library Holdings

Hofstra University Film Library Holdings TITLE PUBLICATION INFORMATION NUMBER DATE LANG 1-800-INDIA Mitra Films and Thirteen/WNET New York producer, Anna Cater director, Safina Uberoi. VD-1181 c2006. eng 1 giant leap Palm Pictures. VD-825 2001 und 1 on 1 V-5489 c2002. eng 3 films by Louis Malle Nouvelles Editions de Films written and directed by Louis Malle. VD-1340 2006 fre produced by Argosy Pictures Corporation, a Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer picture [presented by] 3 godfathers John Ford and Merian C. Cooper produced by John Ford and Merian C. Cooper screenplay VD-1348 [2006] eng by Laurence Stallings and Frank S. Nugent directed by John Ford. Lions Gate Films, Inc. producer, Robert Altman writer, Robert Altman director, Robert 3 women VD-1333 [2004] eng Altman. Filmocom Productions with participation of the Russian Federation Ministry of Culture and financial support of the Hubert Balls Fund of the International Filmfestival Rotterdam 4 VD-1704 2006 rus produced by Yelena Yatsura concept and story by Vladimir Sorokin, Ilya Khrzhanovsky screenplay by Vladimir Sorokin directed by Ilya Khrzhanovsky. a film by Kartemquin Educational Films CPB producer/director, Maria Finitzo co- 5 girls V-5767 2001 eng producer/editor, David E. Simpson. / una produzione Cineriz ideato e dirètto da Federico Fellini prodotto da Angelo Rizzoli 8 1/2 soggètto, Federico Fellini, Ennio Flaiano scenegiatura, Federico Fellini, Tullio Pinelli, Ennio V-554 c1987. ita Flaiano, Brunello Rondi. / una produzione Cineriz ideato e dirètto da Federico Fellini prodotto da Angelo Rizzoli 8 1/2 soggètto, Federico Fellini, Ennio Flaiano scenegiatura, Federico Fellini, Tullio Pinelli, Ennio V-554 c1987. -

Programme De Salle

CINE CLUB DES FESTIVAL D'AUTOMNE JACQUES BECKER RÉTROSPECTIVE INTÉGRALE ROBERT FRANK SEMAINE DES CAHIERS AVANT-PREMIÈRES DU 11 AU 24 DÉCEMBRE UGC MARBEUF, 34, RUE MARBEUF 75008 PARIS DU 25 AU 7 JANVIER 14 JUILLET-PARNASSE, 11, RUE JULES CHAPLAIN 75006 PARIS GRMUITAUX SUPPLÉMENT 378. DUCINÉMA CAHIERS Document de communication du Festival d'Automne à Paris - tous droits réservés MARIN KARMITZ EDITEUR ET MARCHAND DE FILMS A PARIS Saison 85/86 L'Histoire Officielle Produit par Hrstorias Onematograficas. Cinemania - Buenos Aires. Prix d'interprétation féminine Cannes 1985. Rendez-vous de décembre LUIS PUENZO Sortie /e 22 Janvier 1986. No Man's Land Festival de Venise. Festival de New York. Feva ALAIN TANNER de Londres 1985. Mettre en relation et confronter des films, des styles, des tendances et bien sûr des époques, écrire La Tentation d'Isabelle avec les écritures des autres pour les faire apparaître JACQUES DOILLON torve le 23 Octobre 19135. sous un jour nouveau, aimer découvrir desfilms et aimer partager ce plaisir, ce sont les enjeux d'une programmation.Une programmationà 'travers Colonel Redl laquelle nous voudrions affirmer unpartipris, Produit par Matin - Objectiv studio, Budapest. Prix du Jury - Festival de Cannes 1985. mélange d'hétérogénéité et d'envie de faire dialoguer ISTVAN SZABO Sortie le 20 Novembre 1985. l'impossible des bouts de cinéma qui se font au quatre coins du monde , avec la part d'utopie que cela suppose. Ainsi, cette année, la coprésence d'un français,trèsfrançais, comme Jacques Sans Toit ni Loi cinéaste Produit par Ciné-Tamaris/films A2. Becker, et d'un photographe-cinéaste américain, très Lion d'Or Venise 1985. -

Neuerwerbungsliste August 2020 Film

NEUERWERBUNGSLISTE AUGUST 2020 FILM (Foto: Moritz Haase / Olaf Janson) Zentral- und Landesbibliothek Berlin Stiftung des öffentlichen Rechts Inhaltsverzeichnis Unser Filmbestand 3 Unsere Empfehlung 5 Unsere Veranstaltungen 7 Neu im Regal 9 Film 5 Stummfilme 9 Film 7 Fernsehserien 10 Film 10 Tonspielfilme 15 Film 19 Kurzspielfilme 39 Film 27 Animation. Anime Serien 40 Film 40 Dokumentarfilme 40 Musi Musikdarbietungen/ Musikvideos 41 K 400 Kinderfilme 45 Ju 400 Jugendfilme 48 Sachfilme nach Fachgebiet 49 Allgemeine Hinweise 55 Seite 2 von 59 Stand vom: 31.08.2020 Neuerwerbungen im Fachbereich Film Unser Filmbestand Die Cinemathek der ZLB bietet den größten, allgemein zugänglichen Filmbestand in einer öffentlichen Bibliothek Deutschlands. Der internationale und vielsprachige Filmbestand umfasst alle Genres: Spielfilme, auch Stummfilme, Fernsehserien, Kinder- und Jugendfilme, Musikfilme und Bühnenaufzeichnungen, Animations- und Experimentalfilme, sowie Dokumentarfilme zu allen Fächern der Bibliothek. Mehr als 65.000 Filme auf über 50.000 DVDs und über 6.000 Blu-ray Discs sind frei zugänglich aufgestellt und ausleihbar. Aus dem Außenmagazin können 20.000 Videokassetten mit zum Teil seltenen Filmen bestellt werden. Seite 3 von 59 Stand vom: 31.08.2020 Neuerwerbungen im Fachbereich Film Sie haben einen Film nicht im Regal gefunden? Unsere Filme sind nach den Anfangsbuchstaben der Regie und die Serien nach dem Originaltitel sortiert. Sachfilme befinden sich häufig am Ende des Regals des passenden Fachbereichs. Es lohnt sich immer auch eine Suche über unseren Bibliothekskatalog. Denn ein Teil unseres Angebotes steht für Sie in unseren Magazinen bereit. Sie können diese Medien über Ihr Bibliothekskonto bestellen und in der Amerika-Gedenkbibliothek oft bereits nach 30-45 Minuten abholen. -

Catalogue 2010

CINE MEAUX CLUB XIIème SAISON septembre 2009 juin 2010 L’ASSO C IATION CINÉ MEAUX CL UB Le Ciné Meaux Club est une association qui a pour objet de promouvoir la culture ciné- matographique et de la diffuser par les films en organisant des débats. L’adhésion à l’association Ciné Meaux Club est de 7 € pour la saison 2009/2010. Vous pouvez adhérer au guichet du Majestic ou par correspondance en nous faisant parve- nir vos coordonnées (nom, prénom, adresse postale, adresse électronique, âge, profes- sion) et votre règlement. En retour, nous vous remettrons votre carte d’adhérent, qu’il conviendra de présenter au guichet du cinéma Majestic avant chaque séance. La carte permet d’accéder aux séances ciné-club, aux séances commerciales complé- mentaires ainsi qu’aux séances Recadrage du Majestic au tarif de 5 €. Toutes les séances associatives non-commerciales sont accompagnées d’une interven- tion d’un spécialiste du cinéma. Néanmoins, la programmation comme la présence des intervenants ou des réalisateurs (leçon de cinéma) restent sous réserves. La Fédération des ciné-clubs s’efforce de fournir à ses adhérents les meilleures copies existantes des films programmés. Toutefois, certains films n’existent que dans des copies dans un état médiocre, mais a priori passable. Le Ciné Meaux Club prend donc le parti de projeter ces films du répertoire, sans pouvoir garantir que la projection se déroule sans incident. L’ÉQUIPE DU CINÉ MEAUX CL UB PRÉSIDENT D’HONNEUR PRÉSIDENT Bertrand Tavernier Jérôme Tisserand Philippe Torreton VICE -P RÉSIDENT PARRAIN -

Gregory Peck CENTENNIAL

ISSUE 76 AFI.com/Silver AFI SILVER THEATRE AND CULTURAL CENTER APRIL 29–JULY 7, 2016 GREGORY PECK CENTENNIAL PLUS DALTON TRUMBO SHAKESPEARE CINEMA DYLAN IN THE MOVIES WAGNER ON SCREEN FESTIVAL OF NEW SPANISH CINEMA WASHINGTON DC FANTASTIC FILM SHOwcASE Contents Special Engagements Special Engagements ......................2, 3 10th Anniversary! Gregory Peck Centennial .............................4 IDIOCRACY – All Tickets $5! Fri, Apr 29, 9:30; Sat, Apr 30, 9:30; Mon, May 2, 5:15; Shakespeare Cinema, Part III ...................6 Tue, May 3, 5:15; Wed, May 4, 5:15; Thu, May 5, 5:15 Stage & Screen .....................................7 Like his 1999 film OFFICE SPACE, Mike Judge’s satirical comedy IDIOCRACY has become a bona fide cult classic since its original Dalton Trumbo: Radical Writer .................8 theatrical release. An army experiment places two exceedingly average Dylan in the Movies .............................10 test subjects — Army Corporal Luke Wilson and prostitute Maya Rudolph Wagner on Screen — in suspended animation. They awake 500 years in the future to ..............................11 discover that America has become exponentially dumber, a dystopian Festival of New Spanish Cinema ...........12 world of commercial oppression, junk food diets, overflowing garbage Jean-Luc Godard: Rare and Restored 12 and crass anti-intellectualism. They are now the two smartest people alive. ...... DIR/SCR/PROD Mike Judge; SCR Etan Cohen; PROD Elysa Koplovitz Dutton. U.S., 2006, color, 84 min. Korean Film Festival DC ........................13 -

Foreign Language Films

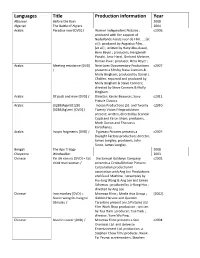

Languages Title Production Information Year Albanian Before the Rain 2008 Algerian The Battle of Algiers 2004 Arabic Paradise now [DVD] / Warner Independent Pictures ; c2006. produced with the support of Nederlands Fonds voor de Film, ... [et al.] ; produced by Augustus Film, ... [et al.] ; written by Hany Abu-Assad, Bero Beyer ; producers, Hengameh Panahi, Amir Harel, Gerhard Meixner, Roman Paul ; producer, Bero Beyer ; Arabic Meeting resistance [DVD] Nine Lives Documentary Productions c2007. / presents a film by Steve Connors & Molly Bingham; produced by Daniel J. Chalfen; reported and produced by Molly Bingham & Steve Connors; directed by Steve Connors & Molly Bingham. Arabic Of gods and men [DVD] / Director: Xavier Beauvois, Sony c2011. Picture Classics. Arabic {02BB}Ajam{012B} Inosan Productions Ltd. and Twenty c2010. {02BB}Ag'ami [DVD] / Twenty Vision Filmproduktion present; written, directed by Scandar Copti and Yaron Shani; producers, Mosh Danon and Thanassis Karathanos. Arabic Iraq in fragments [DVD] / Typecast Pictures presents a c2007. Daylight Factory production; director, James Longley; producers, John Sinno, James Longley. Bengali The Apu Trilogy 2008 Cheyenne Windwalker 2003 Chinese Yin shi nan nü [DVD] = Eat the Samuel Goldwyn Company c2002. drink man woman / presents a Central Motion Pictures Corporation production in association with Ang Lee Productions and Good Machine ; screenplay by Hui-Ling Wang & Ang Lee and James Schamus ; produced by Li-Kong Hsu ; directed by Ang Lee. Chinese Iron monkey [DVD] = Miramax Films ; Media Asia Group ; [2002]. Siunin wong fei-hung tsi Golden Harvest and Quentin titmalau / Tarantino present an LS Pictures Ltd. Film Work Shop production ; written by Tsui Hark ; producer, Tsui Hark ; director, Yuen Wo Ping. -

September 28–October 15, 2017 . Filmlinc.Org/Nyff Table of Contents

SEPTEMBER 28–OCTOBER 15, 2017 . FILMLINC.ORG/NYFF TABLE OF CONTENTS Schedule 2 Spotlight on Documentary 46 Main Slate 6 Projections 56 Shorts 20 Retrospective: Robert Mitchum Centenary 64 Talks 22 Artist Initiatives 80 Special Events 24 Film Society Board & Staff 82 Convergence 32 About the Film Society 84 Revivals 36 NEW YORK FILM FESTIVAL PROGRAMMERS SELECTION COMMITTEE MAIN SLATE . REVIVALS . SPOTLIGHT ON DOCUMENTARY Kent Jones Chair Florence Almozini Associate Director of Programming, Film Society of Lincoln Center (FSLC) Dennis Lim Director of Programming, FSLC Amy Taubin Contributing Editor, Film Comment and Artforum CONVERGENCE PROJECTIONS RETROSPECTIVE Matt Bolish Dennis Lim & Aily Nash Kent Jones & Dan Sullivan SHORTS Narrative: Gabi Madsen . Genre Stories: Laura Kern . New York Stories: Dan Sullivan . Documentary: Tyler Wilson NYFF 4C MAG - FULL PAGE INSIDE FRONT COVER AMA1157 ISSUE DATE: XX/XX/17 FINAL2 DUE DATE: 08/24/17 08/24/17 10:45AM ES MECHANICAL SIZE TRIM: 8.25"W x 8.5"H LIVE: 7.75"W x 8"H BLEED: 8.5"W x 8.75"H SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY 28 29 30 SECTIONS: VENUES: OPENING NIGHT 4:00 Story of G.I. Joe ret/wrt 12:30 Four Sisters: se/ath 6:00 Last Flag Flying ms/ath 6:00 Mrs. Hyde ms/ath Hippocratic Oath cvg CONVERGENCE ALICE TULLY HALL 6:15 Last Flag Flying ms/wrt 6:00 Daughter of the Nile rev/fbt 12:45 New York Shorts sho/wrt ath West 65th Street at Broadway 9:00 Last Flag Flying ms/ath 6:30 El mar la mar doc/wrt 1:30 The Wonderful Country ret/fbt doc SPOTLIGHT ON DOCUMENTARY 9:15 Last Flag Flying ms/wrt 6:30 His Kind of Woman ret/hgt 3:00 Western ms/ath DOWNLOAD THE FILM SOCIETY APP! ELINOR BUNIN MUNROE FILM CENTER 7:00 VR and the Future of cvg/amp 3:00 No Stone Unturned doc/wrt ms MAIN SLATE 144 West 65th Street Virtual Production 3:00 The Old Dark House rev/hgt amp AMPHITHEATER by Lucasfilm (Free Talk) 4:00 Documentary Shorts sho/fbt pjt PROJECTIONS 8:30 The Square ms/ath 5:00 Pursued ret/hgt ebm LOBBY 8:30 Casa de Lava rev/fbt 6:00 Zama ms/ath FILMLINC.ORG/NYFF .