The Altering

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum Rivette: Texts and Interviews (editor, 1977) Orson Welles: A Critical View, by André Bazin (editor and translator, 1978) Moving Places: A Life in the Movies (1980) Film: The Front Line 1983 (1983) Midnight Movies (with J. Hoberman, 1983) Greed (1991) This Is Orson Welles, by Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich (editor, 1992) Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (1995) Movies as Politics (1997) Another Kind of Independence: Joe Dante and the Roger Corman Class of 1970 (coedited with Bill Krohn, 1999) Dead Man (2000) Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (2000) Abbas Kiarostami (with Mehrmax Saeed-Vafa, 2003) Movie Mutations: The Changing Face of World Cinephilia (coedited with Adrian Martin, 2003) Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons (2004) Discovering Orson Welles (2007) The Unquiet American: Trangressive Comedies from the U.S. (2009) Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Film Culture in Transition Jonathan Rosenbaum the university of chicago press | chicago and london Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote for many periodicals (including the Village Voice, Sight and Sound, Film Quarterly, and Film Comment) before becoming principal fi lm critic for the Chicago Reader in 1987. Since his retirement from that position in March 2008, he has maintained his own Web site and continued to write for both print and online publications. His many books include four major collections of essays: Placing Movies (California 1995), Movies as Politics (California 1997), Movie Wars (a cappella 2000), and Essential Cinema (Johns Hopkins 2004). The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2010 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema to Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

Robert Phillip Kolker The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/8 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Robert Kolker is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Maryland and Lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. His works include A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg Altman; Bernardo Bertolucci; Wim Wenders (with Peter Beicken); Film, Form and Culture; Media Studies: An Introduction; editor of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey: New Essays and The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies. http://www.virginia.edu/mediastudies/people/adjunct.html Robert Phillip Kolker THE ALTERING EYE Contemporary International Cinema Revised edition with a new preface and an updated bibliography Cambridge 2009 Published by 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com First edition published in 1983 by Oxford University Press. © 2009 Robert Phillip Kolker Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Cre- ative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 2.0 UK: England & Wales Licence. This licence allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author -

Guide to the Papers of the Capri Community Film Society

Capri Community Film Society Papers Guide to the Papers of the Capri Community Film Society Auburn University at Montgomery Archives and Special Collections © AUM Library Written By: Rickey Best & Jason Kneip Last Updated: 2/19/2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS Content Page # Collection Summary 2 Administrative Information 2 Restrictions 2-3 Index Terms 3 Agency History 3-4 1 of 64 Capri Community Film Society Papers Scope and Content 5 Arrangement 5-10 Inventory 10- Collection Summary Creator: Capri Community Film Society Title: Capri Community Film Society Papers Dates: 1983-present Quantity: 6 boxes; 6.0 cu. Ft. Identification: 92/2 Contact Information: AUM Library Archives & Special Collections P.O. Box 244023 Montgomery, AL 36124-4023 Ph: (334) 244-3213 Email: [email protected] Administrative Information Preferred Citation: Capri Community Film Society Papers, Auburn University Montgomery Library, Archives & Special Collections. Acquisition Information: The collection began with an initial transfer on September 19, 1991. A second donation occurred in February, 1995. Since then, regular donations of papers occur on a yearly basis. Processed By: Jermaine Carstarphen, Student Assistant & Rickey Best, Archivist/Special Collections Librarian (1993); Jason Kneip, Archives/Special Collections Librarian. Samantha McNeilly, Archives/Special Collections Assistant. 2 of 64 Capri Community Film Society Papers Restrictions Restrictions on access: Access to membership files is closed for 25 years from date of donation. Restrictions on usage: Researchers are responsible for addressing copyright issues on materials not in the public domain. Index Terms The material is indexed under the following headings in the Auburn University at Montgomery’s Library catalogs – online and offline. -

LE TEMPS DES NABABS Une Série Documentaire De Florence Strauss Les Films D’Ici Et Le Pacte Présentent

COMMENT PRODUISAIT-ON AVANT LA TÉLÉVISION ? LE TEMPS DES NABABS Une série documentaire de Florence Strauss Les Films d’Ici et Le Pacte présentent COMMENT PRODUISAIT-ON AVANT LA TÉLÉVISION ? LE TEMPS DES NABABS Une série documentaire de Florence Strauss 8 x 52min – France – 2019 – Flat - stéréo À PARTIR DU 12 OCTOBRE SUR CINÉ + CLASSIC RELATIONS PRESSE Marie Queysanne Assistée de Fatiha Zeroual Tél. : 01 42 77 03 63 [email protected] [email protected] SYNOPSIS LISTE DES ÉPISODES Pierre Braunberger, Anatole Dauman, Robert Dorfmann, les frères ÉPISODE 1 : LES ROMANESQUES Hakim, Mag Bodard, Alain Poiré, Pierre Cottrell, Albina du Boisrouvray, Robert et Raymond Hakim - Casque d’Or Jacques Perrin, Jean-Pierre Rassam et bien d’autres… Ils ont toujours André Paulvé - La Belle et la Bête oeuvré dans l’ombre et sont restés inconnus du grand public. Pourtant Alexandre Mnouchkine et Georges Dancigers - Fanfan La Tulipe ils ont produit des films que nous connaissons tous, deLa Grande Henri Deutschmeister - French Cancan vadrouille à La Grande bouffe, de Fanfan la tulipe à La Maman et la putain, de Casque d’or à La Belle et la bête. ÉPISODE 2 : LES TENACES Robert Dorfmann - Jeux interdits Autodidactes, passionnés, joueurs, ils ont financé le cinéma avec une Pierre Braunberger - Une Histoire d’eau inventivité exceptionnelle à une époque où ni télévisions, ni soficas ou Anatole Dauman - Nuit et brouillard autres n’existaient. Partis de rien, ils pouvaient tout gagner… ou bien tout perdre. Ce sont des personnages hauts en couleur, au parcours ÉPISODE 3 : LES AUDACIEUX souvent digne d’une fiction. -

Pdf-Collections-.Pdf

1 Directors p.3 Thematic Collections p.21 Charles Chaplin • Abbas Kiarostami p.4/5 Highlights from Lobster Films p.22 François Truffaut • David Lynch p.6/7 The RKO Collection p.23 Robert Bresson • Krzysztof Kieslowski p.8/9 The Kennedy Films of Robert Drew p.24 D.W. Griffith • Sergei Eisenstein p.10/11 Yiddish Collection p.25 Olivier Assayas • Alain Resnais p.12/13 Themes p.26 Jia Zhangke • Gus Van Sant p.14/15 — Michael Haneke • Xavier Dolan p.16/17 Buster Keaton • Claude Chabrol p.18/19 Actors p.31 Directors CHARLES CHAPLIN THE COMPLETE COLLECTION AVAILABLE IN 2K “A sort of Adam, from whom we are all descended...there were two aspects of — his personality: the vagabond, but also the solitary aristocrat, the prophet, the The Kid • Modern Times • A King in New York • City Lights • The Circus priest and the poet” The Gold Rush • Monsieur Verdoux • The Great Dictator • Limelight FEDERICO FELLINI A Woman of Paris • The Chaplin Revue — Also available: short films from the First National and Keystone collections (in 2k and HD respectively) • Documentaries Charles Chaplin: the Legend of a Century (90’ & 2 x 45’) • Chaplin Today series (10 x 26’) • Charlie Chaplin’s ABC (34’) 4 ABBas KIAROSTAMI NEWLY RESTORED In 2K OR 4K “Kiarostami represents the highest level of artistry in the cinema” — MARTIN SCORSESE Like Someone in Love (in 2k) • Certified Copy (in 2k) • Taste of Cherry (soon in 4k) Shirin (in 2k) • The Wind Will Carry Us (soon in 4k) • Through the Olive Trees (soon in 4k) Ten & 10 on Ten (soon in 4k) • Five (soon in 2k) • ABC Africa (soon -

Gérard Depardieu, Innocent

gérard depardieu gérard In his proto-memoir Innocent, world-renowned actor Gérard Depardieu Gérard Depardieu reflects on his life as if from afar, like a bird surveying a wide horizon, presenting fervent obser- vations on friendship, cinema, religion, politics, & more. From his early days in the theater and his friendships with Jean Gabin and others to his rise in the cinema, this light, vibrant, but searching book offers us an intimate entry into the thinking process of one of cinema’s most mercurial& impassioned actors. Depardieu also touches upon contro- versial topics such as his relationship with Putin & issues Innocent that have led to skirmishes with the press and public. At bottom, Innocent is less a memoir & more the account of a man in search of faith, the faith that is of an innocent mystic, and includes passages about Depardieu’s explora- tions of Islam, Buddhism, and other religions. Espousing a notion of innocence that calls us to move be- yond dogma and ideology, Depardieu urges us to engage with others with respect, receptivity, and mindfulness. In these combative and divisive times, we believe this is a vital if not necessary book, one that could continue and extend dialogues about questions of faith, politics,& religion. isbn 978–1–940625–24–9 www.contramundum.net INNOCENT Gérard Depardieu INNOCENT translated by rainer j. hanshe Innocent © 2015 Le cherche midi Library of Congress éditeur; translation © 2017 Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Rainer J. Hanshe Depardieu, Gérard, 1948– [ Innocent. English.] First Contra Mundum Press Innocent / Gérard Depardieu ; Edition 2017. translated from the French by All Rights Reserved under Rainer J. -

Keeping Apuleius in the Picture a Dialogue Between Buñuel’S Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie and the Metamorphoses of Apuleius

Keeping Apuleius In The Picture A dialogue between Buñuel’s Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie and The Metamorphoses of Apuleius PAULA JAMES Open University UK Summary This article explores common motifs and narrative strategies which appear in the work of the second century CE Latin author, Apuleius, and the twentieth century Spanish film director Luis Buñuel. The use of narration to delay nutri- tion is a vital starting point for the comparative analysis. The focus of both these ‘texts’ makes them appropriate (though in some senses arbitrary) an- chors in what could eventually and fruitfully develop into a wide-ranging dis- cussion: i.e. the extent and significance of culinary metaphors in literary and cinematic narratives within a broad cultural spectrum. Uses and abuses of food and food consumption in both Apuleius and Buñuel intensify the bizarre at- mospheres of the stories. By means of diversionary and supernatural tales my chosen storytellers encourage their audiences to embrace credulity and to question the reality of appearances and consequently they subvert faith in the real world. In their hands magic and the surreal is an experimental strategy for producing a deeper insight into custom and society, not so much a message as an experience for the reader and the viewer, and one which shakes compla- cency about the solidity of social structures and physical forms. Introduction (trailer) Nihil impossibile arbitror sed utcumque fata decreverint, ita cuncta mor- talibus provenire. nam et mihi et tibi et cunctis hominibus multa usu ve- nire mira et paene infecta, quae tamen ignaro relata fidem perdant. (Apuleius’ hero, Lucius, Met.1.20) 186 PAULA JAMES ‘ “Well,” I said, “I consider nothing to be impossible. -

Buñuel by Dali

Luis Buñuel (Luis Buñuel Portolés, 22 February 1900, Calanda, Spain—29 July 1983, Mexico City, Mexico,cirrhosis of the liver) became a controversial and internationally-known filmmaker with his first film, the 17-minute Un Chien andalou 1929 (An Andalousian Dog), which he made with Salvador Dali. He wrote and directed 33 other films, most of them interesting, many of them considered masterpieces by critics and by fellow filmmakers. Some of them are : Cet obscur objet du désir 1977 (That Obscure Object of Desire), Le Charme discret de la bourgeoisie 1972 (The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie), Tristana 1970, La Voie lactée 1969 (The Milky Way), Belle de Jour 1967, Simón del desierto 1965 (Simon of the Desert), El Ángel Exterminador/Exterminating Angel 1962, 25 October 2005 XI:9 Viridiana 1961, Nazarín 1958, Subida al cielo DIARY OF A CHAMBERMAID/LE JOURNAL 1952 (Ascent to Heaven, Mexican Bus Ride), D'UNE FEMME DE CHAMBRE. (1964) 101 Los Olvidados 1950 (The Young and the minutes Damned), Las Hurdes 1932 (Land Without Bread ), and L’Âge d'or 1930 (Age of Gold). His Jeanne Moreau...Céléstine autobiography, My Last Sigh (Vintage, New Georges Géret...Joseph York) was published the year after his death. Daniel Ivernel...Captain Mauger Some critics say much of it is apocryphal, the Françoise Lugagne...Madame Monteil screenwriter Jean-Claude Carrière (who Muni...Marianne collaborated with Buñuel on six scripts), claims Jean Ozenne...Monsieur Rabour he wrote it based on things Buñel said. Michel Piccoli...Monsieur Monteil Whatever: it’s a terrific -

Cinema 2: the Time-Image

m The Time-Image Gilles Deleuze Translated by Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Caleta M IN University of Minnesota Press HE so Minneapolis fA t \1.1 \ \ I U III , L 1\) 1/ ES I /%~ ~ ' . 1 9 -08- 2000 ) kOTUPHA\'-\t. r'Y'f . ~ Copyrigh t © ~1989 The A't1tl ----resP-- First published as Cinema 2, L1111age-temps Copyright © 1985 by Les Editions de Minuit, Paris. ,5eJ\ Published by the University of Minnesota Press III Third Avenue South, Suite 290, Minneapolis, MN 55401-2520 f'tJ Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 1'::>55 Fifth printing 1997 :])'''::''531 ~ Library of Congress Number 85-28898 ISBN 0-8166-1676-0 (v. 2) \ ~~.6 ISBN 0-8166-1677-9 (pbk.; v. 2) IJ" 2. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or othenvise, ,vithout the prior written permission of the publisher. The University of Minnesota is an equal-opportunity educator and employer. Contents Preface to the English Edition Xl Translators'Introduction XV Chapter 1 Beyond the movement-image 1 How is neo-realism defined? - Optical and sound situations, in contrast to sensory-motor situations: Rossellini, De Sica - Opsigns and sonsigns; objectivism subjectivism, real-imaginary - The new wave: Godard and Rivette - Tactisigns (Bresson) 2 Ozu, the inventor of pure optical and sound images Everyday banality - Empty spaces and stilllifes - Time as unchanging form 13 3 The intolerable and clairvoyance - From cliches to the image - Beyond movement: not merely opsigns and sonsigns, but chronosigns, lectosigns, noosigns - The example of Antonioni 18 Chapter 2 ~ecaPitulation of images and szgns 1 Cinema, semiology and language - Objects and images 25 2 Pure semiotics: Peirce and the system of images and signs - The movement-image, signaletic material and non-linguistic features of expression (the internal monologue). -

ETHAN HAWKE the Truth a Film by KORE-EDA HIROKAZU 3B PRODUCTIONS, BUN-BUKU and M.I MOVIES Present

CATHERINE DENEUVE JULIETTE BINOCHE ETHAN HAWKE the truth a film by KORE-EDA HIROKAZU 3B PRODUCTIONS, BUN-BUKU and M.I MOVIES present CATHERINE DENEUVE JULIETTE BINOCHE ETHAN HAWKE the truth (la vérité) a film by KORE-EDA HIROKAZU 107 MIN – FRANCE – 2019 – 1.85 – 5.1 INTERNATIONAL PR MANLIN STERNER [email protected] mobile: +46 76 376 9933 SYNOPSIS Fabienne is a star – a star of French cinema. She reigns amongst men who love and admire her. When she publishes her memoirs, her daughter Lumir returns from New York to Paris with her husband and young child. The reunion between mother and daughter will quickly turn to confrontation: truths will be told, accounts settled, loves and resentments confessed. photo © Rinko Kawauchi © Rinko photo DIRECTOR’S NOTE If I dared to take on the challenge I wanted the story to take place I wanted a film that was not only THE TRUTH is the result of all the of shooting a first film abroad – in in autumn because I wanted to serious but also light-hearted, where efforts and the confidence that my a language that’s not my own and superimpose what the heroine drama and comedy coexist, as actors and crew put in me; it was with a totally French crew – it’s only goes through at the end of her life they do in real life. I hope that the made by the best of professionals, because I was lucky enough to meet onto the landscapes of Paris at the chemistry between the actors and the beginning with my director of actors and collaborators who wanted end of summer. -

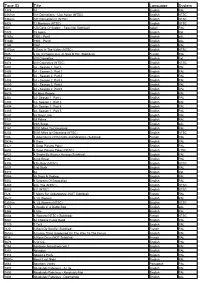

Tape ID Title Language System

Tape ID Title Language System 1375 10 English PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English NTSC 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian PAL 1078 18 Again English Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English pAL 1244 1941 English PAL 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English NTSC f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French PAL 1304 200 Cigarettes English Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English NTSC 2401 24 - Season 1, Vol 1 English PAL 2406 24 - Season 2, Part 1 English PAL 2407 24 - Season 2, Part 2 English PAL 2408 24 - Season 2, Part 3 English PAL 2409 24 - Season 2, Part 4 English PAL 2410 24 - Season 2, Part 5 English PAL 5675 24 Hour People English PAL 2402 24- Season 1, Part 2 English PAL 2403 24- Season 1, Part 3 English PAL 2404 24- Season 1, Part 4 English PAL 2405 24- Season 1, Part 5 English PAL 3287 28 Days Later English PAL 5731 29 Palms English PAL 5501 29th Street English pAL 3141 3000 Miles To Graceland English PAL 6234 3000 Miles to Graceland (NTSC) English NTSC f103 4 Adventures Of Reinette and Mirabelle (Subtitled) French PAL 0514s 4 Days English PAL 3421 4 Dogs Playing Poker English PAL 6607 4 Dogs Playing Poker (NTSC) English nTSC g033 4 Shorts By Werner Herzog (Subtitled) English PAL 0160 42nd Street English PAL 6306 4Th Floor (NTSC) English NTSC 3437 51st State English PAL 5310 54 English Pal 0058 55 Days At Peking English PAL 3052 6 Degrees Of Separation English PAL 6389 60s, The (NTSC) English NTSC 6555 61* (NTSC) English NTSC f126 7 Morts Sur Ordonnance (NOT Subtitled) French PAL 5623 8 1/2 Women English PAL 0253sn 8 1/2 Women (NTSC) English NTSC 1175 8 Heads In A Duffel Bag English pAL 5344 8 Mile English PAL 6088 8 Women (NTSC) (Subtitled) French NTSC 5041 84 Charing Cross Road English PAL 1129 9 To 5 English PAL f220 A Bout De Souffle (Subtitled) French PAL 0652s A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum English PAL f018 A Nous Deux (NOT Subtitled) French PAL 3676 A.W.O.L.