Myths and Realities of Humanitarian Work Monthly Humanitarian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Censo General 2005

DEPARTAMENTO ADMINISTRATIVO NACIONAL DE ESTADISTICA5 Libertad y Orden CENSOCENSO GENERALGENERAL 20052005 REPÚBLICA DE COLOMBIA Junio 13 de 2006 DEPARTAMENTO ADMINISTRATIVO NACIONAL DE ESTADISTICA DEPARTAMENTO ADMINISTRATIVO Cucuta NACIONAL DE ESTADISTICA5 DEPARTAMENTO ADMINISTRATIVO NACIONAL DE ESTADISTICA5 1 CÚCUTA. Censos de Población 1951-2005 1.400.000 5 77 1.200.000 6. 8 19 13 1. 8. 1.000.000 05 1. 0 as 800.000 62 on 5 9. s r 78 0.51 pe l 2 69 ta 600.000 o T 7.74 1 53 400.000 48 7. 38 200.000 0 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 1 González, Río de Oro, Cúcuta, Abrego, Arboledas, Bochalema, Bucarasica, Cachirá, Chinácota, Convención, Cucutilla, Durania, El Carmen, El Tarra, El Zulia, Gramalote, Hacarí, Herrán, La Playa, Los Patios, Lourdes, Mutiscua, Ocaña, Pamplona, Pamplonita, Puerto Santander, Ragonvalia, Salazar, San Calixto, San Cayetano, Santiago, Sardinata, Teorama, Tibú, Villa Caro, Villa del Rosario, California, Charta, Matanza, Surata, Tona, Vetas Censos 1951, 1964 y 1973 no comparable segregación DEPARTAMENTO ADMINISTRATIVO NACIONAL DE ESTADISTICA5 1 CÚCUTA. Personas por hogar 1973-2005 7,00 6,00 99 5, 5,00 gar 4,74 ho 35 9 4, 0 por 4,00 4, nas o s r e P 3,00 2,00 1,00 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 1 González, Río de Oro, Cúcuta, Abrego, Arboledas, Bochalema, Bucarasica, Cachirá, Chinácota, Convención, Cucutilla, Durania, El Carmen, El Tarra, El Zulia, Gramalote, Hacarí, Herrán, La Playa, Los Patios, Lourdes, Mutiscua, Ocaña, Pamplona, Pamplonita, Puerto Santander, Ragonvalia, Salazar, San Calixto, San Cayetano, Santiago, -

Directorio Alcaldes Norte De Santander 2020-2023

DIRECTORIO ALCALDES NORTE DE SANTANDER 2020-2023 MUNICIPIO NOMBRES Y APELLIDOS DIRECCION TELÉFONO CORREO ELECTRONICO PAGINA WEB Calle 14 con Carrera 5ª - Esquina Parque Abrego Juan Carlos Jácome Ropero 097 5642072 [email protected] abrego-nortedesantander.gov.co Principal Carrera 6 No. 2-25, Sector el Hospital - Arboledas Wilmer José Dallos 3132028015 [email protected] arboledas-nortedesantander.gov.co Palacio Municipal Bochalema Duglas sepúlveda Contreras Calle 3 No. 3 - 08 Palacio Municipal 097-5863014 [email protected] bochalema-nortedesantander.gov.co Bucarasica Israel Alonso Verjel Tarazona Calle 2 No. 3-35 - Palacio Municipal 3143790005 [email protected] bucarasica-nortedesantander.gov.co Cáchira Javier Alexis Pabón Acevedo Carrera 6 No.5-110 Barrio Centro 5687121 [email protected] Cácota Carlos Augusto Flórez Peña Carrera 3 Nº 3-57 - Barrio Centro 5290010 [email protected] cacota-nortedesantander.gov.co Carrera 4 No. 4-15 Palacio Municipal-Barrio Chinácota José Luis Duarte Contreras 5864150 [email protected] chinacota-nortedesantander.gov.co El Centro Chitagá Jorge Rojas Pacheco XingAn Street No.287 5678002 [email protected] chitaga-nortedesantander.gov.co Convención Dimar Barbosa Riobo Carrera 6 No. 4 -14 Parque Principal Esquina 5630 840 [email protected] convencion-nortedesantander.gov.co Calle 11 No. 5-49 Palacio Municipal Barrio: Cúcuta Jairo Tomas Yáñez Rodríguez 5784949 [email protected] cucuta-nortedesantander.gov.co Centro Carrera 3ra con Calle 3ra Esquina Barrio El Cucutilla Juan Carlos Pérez Parada 3143302479 [email protected] cucutilla-nortedesantander.gov.co Centro Nelson Hernando Vargas Avenida 2 No. -

BOCHALEMA NORTE DE SANTANDER Corporación Nueva Sociedad De La Región Nororiental De Colombia CONSORNOC

BOCHALEMA NORTE DE SANTANDER Corporación Nueva Sociedad de la Región Nororiental de Colombia CONSORNOC Entidades Socias Fotografías Arquidiócesis de Nueva Pamplona. Archivo Consornoc con apoyo de Diócesis de Cúcuta. Entidades Ejecutoras Diócesis de Ocaña. y Organizaciones de Base Diócesis de Tibú. Cámara de Comercio de Pamplona. Impresión Cámara de Comercio de Ocaña. maldonadográfico Cámara de Comercio de Cúcuta. Universidad de Pamplona. CONSORNOC Universidad Francisco de Paula Santander. Sede principal Pamplona Carrera 5 Nº 5 – 88 Centro Fundador Pamplona, Monseñor Gustavo Martínez Frías Norte de Santander, Colombia Q.E.P.D. Teléfonos: (7) 5682949 Fax (7) 5682552 Presidente www.consornoc.org.co Dr. Héctor Miguel Parra López E-mail: [email protected] Rector Universidad Francisco de Paula Santander Sede Cúcuta E-mail: [email protected] Dirección Ejecutiva Pbro. Juan Carlos Rodríguez Rozo Sede Ocaña E-mail: [email protected] Coordinación General Hermana Elsa Salazar Sánchez Comité de Redacción Daniel Cañas Camargo Martha Miranda Miranda Nancy Torres Rico Se terminó de imprimir en abril de 2010 Sistematización Leandro Enrique Ramos Solano Liliana Esperanza Prieto Villamizar Alix Teresa Moreno Quintero Esta publicación se elabora en el Marco del II Laboratorio de Paz y cuenta con la ayuda financiera de la Unión Europea. Su contenido es responsabilidad de la Corporación Nueva Sociedad de la Región Nororiental de Colombia- Consornoc y en ningún momento refleja el punto de vista o la opinión de la Unión Europea o Acción -

RAGONVALIA NORTE DE SANTANDER Corporación Nueva Sociedad De La Región Nororiental De Colombia CONSORNOC

RAGONVALIA NORTE DE SANTANDER Corporación Nueva Sociedad de la Región Nororiental de Colombia CONSORNOC Entidades Socias Fotografías Arquidiócesis de Nueva Pamplona. Archivo Consornoc con apoyo de Diócesis de Cúcuta. Entidades Ejecutoras Diócesis de Ocaña. y Organizaciones de Base Diócesis de Tibú. Cámara de Comercio de Pamplona. Impresión Cámara de Comercio de Ocaña. maldonadográfico Cámara de Comercio de Cúcuta. Universidad de Pamplona. CONSORNOC Universidad Francisco de Paula Santander. Sede principal Pamplona Carrera 5 Nº 5 – 88 Centro Fundador Pamplona, Monseñor Gustavo Martínez Frías Norte de Santander, Colombia Q.E.P.D. Teléfonos: (7) 5682949 Fax (7) 5682552 Presidente www.consornoc.org.co Dr. Héctor Miguel Parra López E-mail: [email protected] Rector Universidad Francisco de Paula Santander Sede Cúcuta E-mail: [email protected] Dirección Ejecutiva Pbro. Juan Carlos Rodríguez Rozo Sede Ocaña E-mail: [email protected] Coordinación General Hermana Elsa Salazar Sánchez Comité de Redacción Daniel Cañas Camargo Martha Miranda Miranda Nancy Torres Rico Se terminó de imprimir en abril de 2010 Sistematización Leandro Enrique Ramos Solano Liliana Esperanza Prieto Villamizar Alix Teresa Moreno Quintero Esta publicación se elabora en el Marco del II Laboratorio de Paz y cuenta con la ayuda financiera de la Unión Europea. Su contenido es responsabilidad de la Corporación Nueva Sociedad de la Región Nororiental de Colombia- Consornoc y en ningún momento refleja el punto de vista o la opinión de la Unión Europea o Acción -

Norte De Santander. Poblacion Estimada 2012 En Edades Simples 0 a 26 Años

NORTE DE SANTANDER. POBLACION ESTIMADA 2012 EN EDADES SIMPLES 0 A 26 AÑOS EDADES SIMPLES EN TOTAL HOMBRES MUJERES AÑOS 0 25.738 13.179 12.559 1 25.474 13.031 12.443 2 25.306 12.934 12.372 3 25.237 12.886 12.351 4 25.267 12.889 12.378 5 25.074 12.780 12.294 6 25.331 12.907 12.424 7 25.685 13.079 12.606 8 26.098 13.284 12.814 9 26.532 13.500 13.032 10 26.996 13.733 13.263 11 27.506 13.984 13.522 12 27.799 14.146 13.653 13 27.784 14.168 13.616 14 27.531 14.090 13.441 15 27.283 14.008 13.275 16 26.989 13.903 13.086 17 26.598 13.730 12.868 18 26.088 13.470 12.618 19 25.500 13.154 12.346 20 24.867 12.815 12.052 21 24.172 12.446 11.726 22 23.540 12.079 11.461 23 23.034 11.751 11.283 24 22.597 11.435 11.162 25 22.127 11.102 11.025 26 21.668 10.775 10.893 FUENTE. DANE - PROYECCIONES DE POBLACIÓN NORTE DE SANTANDER. POBLACIÓN ESTIMADA 2012 POR GRUPOS DE EDAD Y SEXO GRUPOS DE EDAD TOTAL HOMBRES MUJERES Total 1.320.777 654.974 665.803 0-4 127.022 64.919 62.103 5-9 128.720 65.550 63.170 10-14 137.616 70.121 67.495 15-19 132.458 68.265 64.193 20-24 118.210 60.526 57.684 25-29 105.540 52.270 53.270 30-34 91.549 44.727 46.822 35-39 80.076 38.752 41.324 40-44 77.848 37.130 40.718 45-49 75.297 36.129 39.168 50-54 65.258 31.388 33.870 55-59 52.567 25.320 27.247 60-64 40.892 19.728 21.164 65-69 30.416 14.479 15.937 70-74 22.866 10.530 12.336 75-79 17.145 7.582 9.563 80 Y MÁS 17.297 7.558 9.739 FUENTE. -

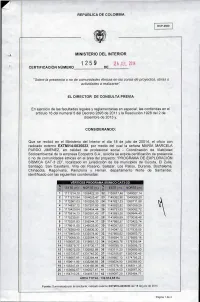

24 Jul 2J3 Certificación Numero De

REPUBLICA DE COLOMBIA [ MINISTERIO DEL INTERIOR 1 2 5 9 24 JUL 2J3 CERTIFICACIÓN NUMERO DE "Sobre la presencia o no de comunidades étnicas en las zonas de proyectos, obras o actividades a realizarse". EL DIRECTOR DE CONSULTA PREVIA En ejercicio de las facultades legales y reglamentarias en especial, las conferidas en el artículo 16 del numeral 5 del Decreto 2893 de 2011 y la Resolución 1928 del 2 de diciembre de 2013 y, CONSIDERANDO: Que se recibió en el Ministerio del Interior el día 18 de julio de 20014, el oficio con radicado externo EXTMII4-0035023, por medio del cual la señora MARIA MARCELA PARDO JIMENEZ, en calidad de profesional social - Coordinación de Viabilidad Socioambiental de la empresa Ecopetrol S.A., solicita se expida certificación de presencia ono de comunidades étnicas en el área del proyecto: "PROGRAMA DE EXPLORACIÓN SISMICA CAT-3 2D", localizado en jurisdicción de los municipios de Cúcuta, El Zulia, Santiago, San Cayetano, Villa de! Rosario, Salazar, Los Patios, Durania, Bochalema, Chinacota, Ragonvalia, Pamplona y Herran, departamento Norte de Santander, identificado con las siguientes coordenadas: • VÉRTICES I(.Ic1J_ I[I.X'_II 1' - ESTE(m) NORTE (M) ESTE (m) NORTE(m) 11171214,10 1356422,30 22 1153617,48 1349027,14 2 1171273,94 1354025,47 23 1149362,90 1349009,20 3 1172561,03 1353295,33 24 1147627,33 1358711,88 4 1174837,12 1357307,60 25 1145520,82 1361059,29 5 1175420,84 1360454,44 26 1148733,93 1365062,72 6 1175814,13 1360381,49 27 1143693,28 1369944,45 7 1175230,01 1357232,53 28 1143668,89 1370036,48 8 1175351,83 -

Beneficiarios Ingreso Solidario

BENEFICIARIOS INGRESO SOLIDARIO Primer Segundo Primer Segundo Identificación Municipio Nombre Nombre Apellido Apellido URIEL BAYONA SANCHEZ 5407225 ABREGO YONY ALEIRO BAYONA PAEZ 88287568 ABREGO LUIS ENRIQUE RODRIGUEZ BOHADA 13315267 ARBOLEDAS FREDDY MONCADA CARRILLO 13412374 ARBOLEDAS PABLO LIZARAZO CASTILLO 13826211 ARBOLEDAS MARIA RAMONA GARCIA PEREZ 27621129 ARBOLEDAS LENNY YOLIMA RUBIO BUITRAGO 43586180 ARBOLEDAS BELCY XXXX ORTEGA SARMIENTO 27633381 BOCHALEMA JOSÉ BENEDICTO VERA ACEVEDO 5415319 BOCHALEMA LUZ MERCEDES RODRIGUEZ BARON 60376564 BOCHALEMA JOSE ANTONIO MALDONADO CONTRERAS 5416416 BUCARASICA EDUARDO RODRIGUEZ PABON 5419701 CÁCHIRA EDELMIRO RINCON PABON 5419930 CÁCHIRA NESTOR DIOMEDES SALAMANCA ACEVEDO 1091452449 CÁCOTA ALIDA TERESA REYES PEÑA 1126430268 CÁCOTA ROSA JULIA ISIDRO CARRILLO 27645177 CÁCOTA NIDIA IVONNE VILLAMIZAR GRANADOS 27645310 CÁCOTA JOSE ANGEL SUAREZ EUGENIO 5418095 CÁCOTA CARMEN YAVIRA VERA 27682754 CHINACOTA LEILA CAROLINA MÜLLER MONSALVE 27682761 CHINACOTA NANCY PATRICIA PÉREZ BAUTISTA 60421094 CHINACOTA EDISSON MARCELO CONTRERAS DELGADO 88181026 CHINACOTA DIOCELINA PEÑA MORENO 27687184 CHITAGA SAMUEL FUENTES CIFUENTES 13170344 CHITAGÁ YOVANY BAYONA GUTIÉRREZ 13378943 CONVENCION LEANDRO ALBERTO DIAZ SOLANO 13379164 CONVENCION ELKIN ARGELIS BERNAL MERCADO 1005042539 CÚCUTA PAMELA PARRA VARGAS 1006291800 CÚCUTA CARLOS NELSON NOCHES QUINTERO 1006890440 CÚCUTA KENER FABIAN RIVERA GOMEZ 1010059298 CÚCUTA JESSICA PAOLA MARIN 1022334159 CÚCUTA CARMEN DE LA 1034281169 HILARIA CONSOLACIÓN ISARRA DELGADO CÚCUTA -

Modelo De Arquitectura Empresarial De La Alcaldía Municipal De Ragonvalia, Norte De Santander

Modelo de Arquitectura Empresarial de la Alcaldía Municipal de Ragonvalia, Norte de Santander Nidia Adriana González Ruiz Universidad EAN Facultad de Ingeniería Maestría en Gerencia de Sistemas de Información y Proyectos Tecnológicos Bogotá, Colombia 2021 Universidad Ean ~ 2 ~ Modelo de Arquitectura Empresarial de la Alcaldía Municipal de Ragonvalia, Norte de Santander Nidia Adriana González Ruiz Trabajo de grado presentado como requisito para optar al título de Magister en gerencia de sistemas de información y proyectos tecnológicos Director (a): Edicson Jair Gil Acosta Modalidad: Trabajo Dirigido Universidad EAN Facultad de Ingeniería Maestría en Gerencia de Sistemas de Información y Proyectos Tecnológicos Bogotá, Colombia 2021 Modelo de Arquitectura Empresarial de la Alcaldía Municipal de ~ 3 ~ Ragonvalia, Norte de Santander NOTA DE ACEPTACIÓN ______________________________ ______________________________ ______________________________ ______________________________ ______________________________ ______________________________ Firma del jurado ______________________________ Firma del jurado ______________________________ Firma del director del trabajo de grado Bogotá D.C. 29 - marzo – 2021 Universidad Ean ~ 4 ~ DEDICATORIA A mi madre (Q.E.P.D), a mi padre, que me enseñaron la importancia de la educación y los valores que me inculcaron, a mis hermanos por sus consejos y mis sobrinos que son mi motivación. La vida nos enseña a aprovechar el tiempo y el tiempo nos enseña a valorar la vida. Anónimo Modelo de Arquitectura Empresarial de la Alcaldía Municipal de ~ 5 ~ Ragonvalia, Norte de Santander AGRADECIMIENTOS Agradezco a Dios por la vida y las oportunidades laborales y de educación que me ha presentado, y por la sabiduría. A mi familia, por el apoyo brindado en cada momento de mi vida. A la Universidad EAN, por brindarme los conocimientos durante dos años de formación de la maestría. -

Texto Completo

Cuadernos sobre Relaciones Internacionales, Regionalismo y Desarrollo / Vol. 12. No. 24. Julio - Diciembre 2017 I.S.S.N:1856-349X Depósito Legal: l.f..07620053303358 El impacto de la política educativa en el desarrollo local: subregión suroriental del departamento Norte de Santander, Colombia Jorge Milton Matajira Vera1 Jorge Eliécer Bautista R.2 Jensy Johanna Romero F.3 Chanberlayn Pinzón4 Uri Gabriel Acuña5 Recibido: 18/07/2017 Aceptado: 23/10/2017 RESUMEN El objetivo del presente trabajo es analizar el impacto que tiene la educación en la subregión suroriental del departamento Norte de Santander, Colombia. En este sentido, se consideran los lineamientos del Ministerio de Educación Nacional, y se analiza el impacto de las líneas estratégicas de éstos en la subregión y luego se contrastan con las vocaciones productivas de los municipios y la misma asociatividad existente tanto en el plano institucional como en el productivo. El estudio asume desde un comienzo la perspectiva del desarrollo humano como el despliegue de habilidades y capacidades para superar las crisis o las situaciones adversas, siendo la educación, a través de su diseño e implementación como política pública, una variable clave del desarrollo. Palabras clave: Desarrollo local, educación, política pública, derechos humanos, frontera. 1 Profesor e investigador de la Escuela Superior de Administración Pública (ESAP)-Colombia. Correo: electrónico: [email protected]. 2 Profesor e investigador de la Escuela Superior de Administración Pública (ESAP)-Colombia. Correo electrónico: [email protected]. 3 Investigadora Junior egresada de la Escuela Superior de Administración Pública (ESAP)- Colombia. Correo electrónico: [email protected]. 4 Auxiliar de investigación, Escuela Superior de Administración Pública (ESAP)-Colombia. -

Plan De Encuestamiento Municipio De Ragonvalia Norte De Santander

PLAN DE ENCUESTAMIENTO MUNICIPIO DE RAGONVALIA NORTE DE SANTANDER Agosto - 2017 TABLA DE CONTENIDO 1. OBJETIVO. 2. ACTIVIDADES GENERALES. 2.1 METODOLOGÍA SELECCIÓN DE ENCUESTAS ÁREA RURAL. 2.2 ESTRATIFICACIÓN Y SELECCIÓN DE VIVIENDAS EN EL ÁREA DISPERSA. 2.3 SELECCIÓN DE VEREDAS POR VISITAR. 2.4 SELECCIÓN DE LAS VIVIENDAS O UNIDADES FINALES DE MUESTREO. 2.5 HOJAS DE RUTA Y SISTEMATIZACIÓN DE LA SELECCIÓN. 3. PLANIFICACIÓN DE ACTIVIDADES DE ENCUESTAMIENTO. 3.1 NÚMERO DE ENCUESTAS A EFECTUAR EN EL MUNICIPIO. 3.2 CRITERIOS DE CAMBIOS PARA EL TRABAJO DE CAMPO. ANEXOS ANEXO A. DISTRIBUCIÓN MUESTRAL ENCUESTA RESIDENCIAL. ANEXO B. DISTRIBUCIÓN MUESTRAL ENCUESTA COMERCIAL Y OTROS SECTORES. BIBLIOGRAFIA Plan de Encuestamiento Municipio de Ragonvalia. 1. Objetivo: Establecer el detalle de las actividades a desarrollar, para la aplicación Encuestamiento en el Municipio de Ragonvalia, según la distribución muestral para Encuesta Residencial, Comercial y Otros Sectores. Ver Anexo A y Anexo B. 2. Actividades Generales: Distribuir el número de encuestas a efectuar en el Municipio, por unidades Residenciales, Industriales, Comerciales e Institucionales. Identificar las áreas geográficas a encuestar y trazar las rutas de acceso a las veredas. Estimar los tiempos de desplazamiento y retorno a los lugares. (Municipio- Vereda-Municipio) Elaborar el cronograma de Encuestamiento. Efectuar la capacitación y asignación del personal de Encuestamiento. Establecer el Plan de Supervisión del Encuestamiento. 2.1 Metodología Selección de Encuestas Área Rural Se toma como referencia, la metodología empleada en Pers ejecutados en años anteriores. A continuación se extrae información importante del documento guía: Metodología de Recolección de Información Primaria PERS Nariño, 2013: Para abordar la selección de viviendas en el área rural, es conveniente tener en cuenta que el DANE considera los centros poblados y las áreas dispersas en la categoría “resto”. -

Municipio De Ragonvalia Norte De Santander Plan Municipal De Gestión Del Riesgo Pmgr

MUNICIPIO DE RAGONVALIA NORTE DE SANTANDER PLAN MUNICIPAL DE GESTIÓN DEL RIESGO PMGR OMAR ADRIAN OCHOA VALDERRAMA ALCALDE 2012 - 2015 Código: GP-F-04 V.00 PLAN MUNICIPAL DE GESTIÓN DEL RIESGO REPÚBLICA DE COLOMBIA Fecha de Página 2 de DEPARTAMENTO NORTE DE SANTANDER Actualización 47 MUNICIPIO DE RAGONVALIA 01/07/2009 ALCALDÍA CONSEJO MUNICIPAL DE GESTIÓN DEL RIESGO CMGR OMAR ADRIAN OCHOA VALDERRAMA ALCALDE LUIS ALBERTO MEZA RODRÍGUEZ SECRETARIO GENERAL DEL MUNICIPIO. CLAUDIA PATRICIA CABANZO BLANCO. SECRETARIO DE PLANEACIÓN. YARIELA JENESSA ACEVEDO DURAN COORDINADOR DE SALUD PÚBLICA LEYDI MAGDIEL TARAZONA YÁÑEZ JEFE DE LA UNIDAD MUNICIPAL DE SERVICIOS PÚBLICOS LUIS LIZCANO CONTRERAS DIRECTOR DE CORPONOR ALEXANDER YÁNEZ BUITRAGO COMANDANTE DEL CUERPO DE BOMBEROS VOLUNTARIOS JULIO CESAR DURÁN MENESES COMANDANTE DE LA ESTACIÓN DE POLICÍA ARGENIS DARÍO SANABRIA LÓPEZ REPRESENTANTE DE LA UMATA. EDILFREDO BOVEA CONTRERAS INSPECTOR DE POLICÍA Y COMISARIO DE FAMILIA ASESOR EN LA FORMULACIÓN DEL PMGR HUGO CESAR VILLAMIZAR GÓMEZ “NUEVAS IDEAS QUE CONSTRUYEN PROGRESO” Calle 6 No. 2-32 PBX (097) 5869047 – 5869155 Fax 5869087 e-mail alcaldí[email protected] Código: GP-F-04 V.00 PLAN MUNICIPAL DE GESTIÓN DEL RIESGO REPÚBLICA DE COLOMBIA Fecha de Página 3 de DEPARTAMENTO NORTE DE SANTANDER Actualización 47 MUNICIPIO DE RAGONVALIA 01/07/2009 ALCALDÍA TABLA DE CONTENIDO Pág. 1. PRESENTACIÓN 4 2. ANTECEDENTES 10 3. OBJETIVOS 12 3.1. OBJETIVO GENERAL 12 3.2. OBJETIVOS ESPECÍFICOS 12 4. POLÍTICAS DEL PLAN 13 5. ESTRATEGIAS DEL PLAN 14 6. ESCENARIOS DE RIESGO 15 6.1. IDENTIFICACIÓN DE ESCENARIOS DE RIESGO. 21 6.2. CONSOLIDACIÓN Y PRIORIZACIÓN DE ESCENARIOS DE RIESGO 22 6.3. -

Tabla De Municipios

NOMBRE_DEPTO PROVINCIA CODIGO_MUNICIPIO NOMBRE_MPIO Nombre Total 91263 EL ENCANTO El Encanto 91405 LA CHORRERA La Chorrera 91407 LA PEDRERA La Pedrera 91430 LA VICTORIA La Victoria 91001 LETICIA Leticia AMAZONAS AMAZONAS 91460 MIRITI - PARANÁ Miriti - Paraná 91530 PUERTO ALEGRIA Puerto Alegria 91536 PUERTO ARICA Puerto Arica 91540 PUERTO NARIÑO Puerto Nariño 91669 PUERTO SANTANDER Puerto Santander 91798 TARAPACÁ Tarapacá Total AMAZONAS 11 05120 CÁCERES Cáceres 05154 CAUCASIA Caucasia 05250 EL BAGRE El Bagre BAJO CAUCA 05495 NECHÍ Nechí 05790 TARAZÁ Tarazá 05895 ZARAGOZA Zaragoza 05142 CARACOLÍ Caracolí 05425 MACEO Maceo 05579 PUERTO BERRiO Puerto Berrio MAGDALENA MEDIO 05585 PUERTO NARE Puerto Nare 05591 PUERTO TRIUNFO Puerto Triunfo 05893 YONDÓ Yondó 05031 AMALFI Amalfi 05040 ANORÍ Anorí 05190 CISNEROS Cisneros 05604 REMEDIOS Remedios 05670 SAN ROQUE San Roque NORDESTE 05690 SANTO DOMINGO Santo Domingo 05736 SEGOVIA Segovia 05858 VEGACHÍ Vegachí 05885 YALÍ Yalí 05890 YOLOMBÓ Yolombó 05038 ANGOSTURA Angostura 05086 BELMIRA Belmira 05107 BRICEÑO Briceño 05134 CAMPAMENTO Campamento 05150 CAROLINA Carolina 05237 DON MATiAS Don Matias 05264 ENTRERRIOS Entrerrios 05310 GÓMEZ PLATA Gómez Plata NORTE 05315 GUADALUPE Guadalupe 05361 ITUANGO Ituango 05647 SAN ANDRÉS San Andrés 05658 SAN JOSÉ DE LA MONTASan José De La Montaña 05664 SAN PEDRO San Pedro 05686 SANTA ROSA de osos Santa Rosa De Osos 05819 TOLEDO Toledo 05854 VALDIVIA Valdivia 05887 YARUMAL Yarumal 05004 ABRIAQUÍ Abriaquí 05044 ANZA Anza 05059 ARMENIA Armenia 05113 BURITICÁ Buriticá