The Book out of Bounds out of Book the Claus Schatz-Jakobsen, Peter Simonsen and Tom Pettitt and Tom Simonsen Peter Claus Schatz-Jakobsen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Most Contagious 2011

MOST CONTAGIOUS 2011 Cover image: Take This LoLLipop / Jason Zada most contagious / p.02 / mosT ConTAGIOUS 2011 / subsCripTion oFFer / 20% disCounT FuTure-prooFing your brain VALid unTiL 9Th JANUARY 2012 offering a saving of £200 gBP chapters / Contagious exists to find and filter the most innovative 01 / exercises in branding, technology, and popular culture, and movemenTs deliver this collective wisdom to our beloved subscribers. 02 / Once a year, we round up the highlights, identify what’s important proJeCTs and why, and push it out to the world, for free. 03 / serviCe Welcome to Most Contagious 2011, the only retrospective you’ll ever need. 04 / soCiaL It’s been an extraordinary year; economies in turmoil, empires 05 / torn down, dizzying technological progress, the evolution of idenTiTy brands into venture capitalists, the evolution of a generation of young people into entrepreneurs… 06 / TeChnoLogy It’s also been a bumper year for the Contagious crew. Our 07 / Insider consultancy division is now bringing insight and inspiration daTa to clients from Kraft to Nike, and Google to BBC Worldwide. We 08 / were thrilled with the success of our first Now / Next / Why event augmenTed in London in December, and are bringing the show to New York 09 / on February 22nd. Grab your ticket here. money We’ve added more people to our offices in London and New 10 / York, launched an office in India, and in 2012 have our sights haCk Culture firmly set on Brazil. Latin America, we’re on our way. Get ready! 11 / musiC 2.0 We would also like to take this opportunity to thank our friends, supporters and especially our valued subscribers, all over the 12 / world. -

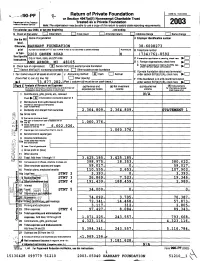

'90-PF ~. Return of Private Foundation

OMB No 1545- 005 2 ;'90-PF ~. Return of Private Foundation or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Department of the Treasury Treated as a Private Foundation Internal Revenue Service Note : The organization may be able to use a copy o/ this return to satisfy state reporting requirements. 2003 For calendar year 2003. or endin Name of organization Employer identification number Use the IRS label . Otherwise, ARHART FOUNDATION J1o-v11 .1161oZ print Numbs and sheet (a P O box numbs d meal is not delivered to street address) RoorNeurte g Telephone number or type. 2200 GREEN ROAD I i ay i i vi-o» .6 See Specific If exemption application is pending, check hers Instructions . City or town, state, and ZIP code 0 1 . Foreign organizations, check here 2, Forsi~ organizations meeting the 85% test, , H Check type of organization : LM Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation check here and attach computation Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust E:J Other taxable private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method : X Cash [ Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here " D (from Part It, Col. (c), tine 16) 0 Other (specify) F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination $ 7 3 8 7 7 2 8 2 . (Part l, column (d) must be on cash basi, under section 507 b 1 B check here pad I Analysis of Revenue and Expenses I Revenue and (C) Adjusted net (d) Disbursements (The total of amounts in columns (b), (c), end (d) may not 1~) (b) Net investment for charitable -

Kaiser Chiefs Never Miss a Beat Mp3, Flac, Wma

Kaiser Chiefs Never Miss A Beat mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Never Miss A Beat Country: Australia Released: 2008 Style: Indie Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1141 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1602 mb WMA version RAR size: 1925 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 395 Other Formats: DMF ADX VOX MOD AAC RA MPC Tracklist Hide Credits Never Miss A Beat Backing Vocals – Anne-Marie Chirema, Lily Allen, Lou Hayter, Sarah Jones Engineer 1 3:10 [Assistant] – Tom Morris Engineer [Mix Engineer] – John O'MahonyMastered By – John Davis Mixed By – Andy WallaceMixed By [Assistant] – Jan Petrov Sooner Or Later 2 3:49 Mastered By – Simon FrancisMixed By – Eliot James Never Miss A Beat (Yuksek Remix) 3 Remix – Yuksek Never Miss A Beat (RAC Remix) 4 Remix – André Allen Anjos Companies, etc. Licensed From – B-Unique Records Credits Engineer – Eliot James, Mark Ronson Engineer [Assistant] – Raj Das, Samuel Navel, Tim Goalen Producer – Eliot James, Mark Ronson Written-By – White*, Baines*, Hodgson*, Wilson*, Rix* Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 9341004002494 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Kaiser Never Miss A Beat (CD, B-Unique BUN145CD BUN145CD Europe 2008 Chiefs Single) Records, Polydor Kaiser Never Miss A Beat B-Unique none none UK 2008 Chiefs (CDr, Single, Promo) Records Kaiser Never Miss A Beat (7", B-Unique BUN1457 BUN1457 UK 2008 Chiefs Single) Records Kaiser Never Miss A Beat B-Unique none none UK 2008 Chiefs (CDr, Single, Promo) Records Kaiser Never Miss A Beat (CD, B-Unique UK & BUN145CDP BUN145CDP 2008 Chiefs Single, Promo) Records Europe Related Music albums to Never Miss A Beat by Kaiser Chiefs Miss Mee Feat. -

The Alchemy of Prague

The Alchemy of Prague with Dan Winter, Vincent Bridges, Erik Berglund & Roger Green 6 days of seminars in the heart of Prague including day trip to Kutna Hora sponsored by www.FengShuiSeminars.com & www.AcademySacredGeometry.com ITINERARY April 9th Highlights International group 6 days of seminars held in the heart of Prague arrives into Prague Teachings from Dan Winter – International expert on Alchemy, Sacred April 10 – 15 Geometry, Bio Feedback, Ancient cultures and Bloodlines, includes Prague 6 day unique teachings from Dan Winter on the alchemist John Dee. seminar & tour. Teachings from Vincent Bridges –Vincent Bridges is an authority on the English Alchemist John Dee. He will be giving numerous presentations at April 16th the Prague Easter event – espeically on the angelic writings of John Dee. Group departs for home Erik Berglund (Celtic Harpist, Tenor and Spiritual Healer). Angelic Harp Music, Singing, and Healing Stories with Erik Berglund. Local guest speakers including Michal Juza, Cheryl Yambrach Rose-Hall, Radovan Foit and Jiri Maria Masek. Visit sacred sites and special off the track locations, walking tours. Visit the ancient alchemical township of Kutna Hora. Prague seminar held in a renovated building completely based on ecological principles and design using green materials – a special place in the heart of Prague, includes vegetarian restaurant and tea house on site. Celebration Saturday dinner and cruise on the beautiful Vltava River. Price includes lunches, transport, and tuition. Accommodation ideas and suggestions based on your price range in Prague. page 2 Prague – The Golden City into the Rosy Heart of Alchemy and the Science of The Sacred o rich and beautiful was The greatest flourishing of Alchemy in Prague five centuries Europe came during the reign of Rudolf ago that it was called 11 (Fifteenth Century), when important “The Golden City” (die Czech and foreign alchemists lived in Goldene Stad) - and the Bohemia. -

Enochian 101

ENOCHIAN 101 Illustration by Michael Arndt - (c) 1997 e.v. AN INTRODUCTION TO ENOCHIAN MAGICK by Christeos Pir (Text of a seminar given at Ecumenicon/Sacred Space VIII, an occult/pagan-oriented ecumenical conference that took place July 13 - 16, 1995 e.v. in Herndon VA.) I. Int roduction II. H istory 1. Dee & Kelley 2. Causabon & Ashmole 3. Golden Dawn 4. Crowley 5. Modern i. Scheuler ii. Church of Satan iii.Aurum Solis iv. Ben Rowe v. Independents III.T he Enochian System 1. Misc. Dee & Kelley i. Requirements (Table, Sigil, etc.) ii. Book of Enoch iii.Tribes of Israel iv. Banners v. 91 Parts (see also Aethyrs, below) 2. Bonorum 3. Elemental Tablets 4. Aethyrs 5. Modern Variations i. Golden Dawn ii. Ben Rowe iii.Various Independents IV.Bi bliography INTRODUCTION "I�m Christeos Pir, and I�m a student of Enochian Magick. I say that not out of formality or false modesty, but because I have a pretty good idea (I hope) of my level of expertise with the Enochian system. Those of you who have some experience with Enochian are invited to chime in with comments or corrections when needed, though if something is a statement of opinion it�d be good to clearly label it as such. Likewise, those new to Enochian are encouraged to speak up with any questions, which I�ll do my best to answer as best I can. If I don�t know the answer, I�ll be glad to make something up on the spot. "So, what is Enochian Magick? Simply put, it is an approach to ceremonial magick based on the alleged conversations between Dr. -

ALE 2006 Nr 4

NR 4 2006 Ale Historisk tidskrift FÖR SKÅNE HALLAND OCH BLEKINGE TEMANUMMER BORNHOLMS LÖSEN F Ale Historisk tidskrift för Skåne, Halland och Blekinge utges av Dc skånska landskapens historiska och arkeologiska förening och Landsarkivet i Lund. Redaktionskomm i tté Docent Peter Carelli, Lund Universitetslektor Gert Jeppsson. Lund, redaktör Museichef Göran Larsson, Lund Docent Sten Skansjö. Lund Professor Anna Christina Ullsparre. Lund Innehåll Sid. Gert Jeppsson: Bornholms lösen Vederlagsgodset i Skåne och Danmark på 1660-talet 1 TRYCKTJÄNST I ESLÖV HB, 2007 BORNHOLMS LOSEN•* Vederlagsgodset i Skåne och Danmark på 1660-talet Gert Jeppsson — ' JiJ c .,_x,/,A «j / Æ pjcirf -- sen S $ íf r i?A o/e/f- \Q W* & A JtAXJ’ j 'O>1 _ý’o ( a C t?A -riv ífJi *»» . føj »wsak fl A R. E 2J-A2 &!ÿÿÿ ß A L V% ■*: £.“ A3 > ? .hct'Æn* CnatrjAM TIC UM 'ÿOTPME * *W _ __ Karta över Bornholm från 1676 med omgivande delar av Skåne och Blekinge. Kolorerad tuschteckning. Storlek: 58 x 56 cm. Tillhör Del Kongelige Bibliotek. København. Kortog Billedafdelingen. Signum: KBK III, 26-0-1676/2. Den latinska titeln; »Hunc Typum insularum Bornholm et Christianoe cum maritimo traetu vicimarum Provinciarum Sac. Reg. Maiest». Innehåll Bornholms lösen Vederlagsgodset i Skåne och Danmark på 1660-talet 4 Inledning 4 Den politiska bakgrunden 5 Stockholmsförhandlingarna 9 Vägen till Malmötraktaten 11 Huvudgårdarna i Bornholms vederlag 14 Ägarebilden 15 Den geografiska fördelningen 16 Taxeringen av godsen 16 Enskildheter i taxeringen 17 Vederlagshuvudgårdarnas storlek 20 Vederlagsgodsets kondition 21 Förändringar för bönderna 22 Huvudgårdarnas användning och betydelse 24 De skånska vederlagsgodsen i Danmark 26 Sammanfattning 29 Tabeller 32 Summary 37 Noter 37 Referenser 39 Karta 40 Några använda förkortningar: b.,bd = band/bind LLA = Landsarkivet i Lund dl. -

Danmarks Kunstbibliotek the Danish National Art Library

Digitaliseret af / Digitised by Danmarks Kunstbibliotek The Danish National Art Library København / Copenhagen For oplysninger om ophavsret og brugerrettigheder, se venligst www.kunstbib.dk For information on copyright and user rights, please consult www.kunstbib.dk . o. (ORPORATfON OF Londoi 7IRTG7ILLE1? IgpLO G U i OF THE LOAN COLLECTIO o f Picture 1907 PfeiCE Sixpence <Art Gallery of the (Corporation o f London. w C a t a l o g u e of the Exhibition of Works by Danish Painters. BY A. G. TEMPLE, F.S.A., Director of the 'Art Gallery of the Corporation of London. THOMAS HENRY ELLIS, E sq., D eputy , Chairman. 1907. 3ntrobuction By A. G. T e m p l e , F.S.A, H E earliest pictures in the present collection are T those of C arl' Gustav Pilo, and Jens Juel. Painted at a time in the 1 8 th century when the prevalent and popular manner was that better known to us by the works o f the notable Frenchmen, Largillibre, Nattier, De Troy and others, these two painters caught something o f the naivété and grace which marked the productions of these men. In so clear a degree is this observed, not so much in genre, as in portraiture, that the presumption is, although it is not on record, at any rate as regards Pilo, that they must both have studied at some time in the French capital. N o other painters of note, indigenous to the soil o f Denmark, had allowed their sense of grace such freedom to so express itself. -

CATS Annual Report 2018

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 CATS Centre for Art Technological Studies and Conservation The centre is a strategic research partnership between three Copenhagen based research institutions Statens Museum for Kunst (SMK) The National Museum of Denmark (NMD) The School of Conservation at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, Schools of Architecture, Design and Conservation (KADK) The cornerstone of CATS is technical art history, which is an interdisciplinary field of research between conservators, natural scientists and scholars from art historical and cultural studies. Technical art history investigates the making and meaning of art works, painting techniques and artists’ materials. A main objective of the research centre is to develop new and more exact methods to diagnose, treat and preserve our art historical heritage. The exploration of artistic practices is aimed at shedding light on the complex and fascinating cartography of ageing processes within works of art – to contribute to and advance the field of technical art history. The establishment of the Centre for Art Technological Studies and Conservation was made possible by a donation by the Villum Foundation and the Velux Foundation, and is a collaborate research venture between Statens Museum for Kunst, the National Museum of Denmark and the School of Conservation at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, Schools of Architecture, Design and Conservation. Contact CATS Website: www.cats-cons.dk E-mail: [email protected] 2 CATS Annual Report, January - December 2018 Contents INTRODUCTION -

The Distribution of Silver Specimens from the Kongsberg Silver Mines, Norway, 17Th and 18Th Centuries

The distribution of silver specimens from the Kongsberg Silver Mines, Norway, 17th and 18th centuries B.I. Berg & F.S. Nordrum Berg, B.L & Nordrum, F.S. The distribution of silver specimens from the Kongsberg Silver Mines, Nor• way, 17th and 18th centuries. In: Winkler Prins, CF. & Donovan, S.K. (eds.), VII International Sympo• sium 'Cultural Heritage in Geosciences, Mining and Metallurgy: Libraries - Archives - Museums': "Museums and their collections", Leiden (The Netherlands), 19-23 May 2003. Scripta Geológica Special Issue, 4: 14-19, 3 figs.; Leiden, August 2004. B.L Berg & F.S. Nordrum, Norwegian Mining Museum, P.O. Box 18, NO-3602 Kongsberg, Norway ([email protected]; [email protected]). Key words — Silver, specimens sales, collections, history, Norway. Specimens of native silver from the Kongsberg mines in Norway are world famous and have been distri• buted through sales and gifts during the whole period of mining from 1623 to 1958. Names of customers, the number of sold specimens and their silver content are documented in accounts which are preserved back to the 1620s. The Danish-Norwegian kings received the largest amounts of silver specimens. Contents Introduction 14 Sales-lists 14 Conclusions 19 Reference and other sources 19 Introduction From their opening in 1623, the Kongsberg Silver Mines have been famous for finds of beautiful silver specimens (Berg & Nordrum, 2003). The Kongsberg ore con• sists mainly of native silver occurring in calcite veins. In cavities in the veins the silver has partly been precipitated as wires and crystals. Such specimens have fascinated miners, visitors and collectors throughout the centuries, and have made Kongsberg a world-famous place among mineral collectors. -

Arguing with Angels

1 The Magus and the Seer A Colloquium of Angels or almost thirty years, a good one-third of a long and productive life, the Elizabethan mathematician, astrologer, alchemist, and Fnatural philosopher John Dee (1527–1608/9) experimented with magic. The goal of these experiments was to make contact with the angels. From around 1580 until his death in the winter of 1608/9 Dee employed at least fi ve different “scryers,” or crystal gazers, to aid him in this pursuit.1 Of these ongoing experiments with various seers, it is the series of sessions with Edward Kelley (1555–1597) that stands out. The relationship between Dee and Kelley, a trained apothecary who had probably been convicted of coining, took place over seven intense years, from 1582 to 1589, vari- ously against the cultural settings of London, Krakow, Prague, and various other Bohemian cities. It was a Europe marked by political intrigue, growing religious confl ict, and strong apocalyptic fervors. Against this background, Kelley introduced Dee to a gallery of angelic beings and heavenly landscapes, ostensibly appearing to him in the crystal, pouring out drops of divine and esoteric secrets to the eager philosopher. Among the wonders were the lost language of Adam, knowledge of the angelic hierarchies, and secrets regarding the imminent apocalypse. In itself, there was nothing new about scrying. Catoptromantic and crystallomantic practices, that is, the use of refl ective surfaces, such as mirrors or crystals to contact spiritual entities, were folk traditions that could easily be traced back to the Middle Ages.2 In Elizabethan England, crystal gazing had become something of an institution, with wandering scryers taking up residence with patrons for shorter periods, to provide their sought-after supernatural services. -

Oslo Katedralskoles Historie 1153–1800 Skolen Og Tiden

Oslo katedralskoles historie 1153–1800 Einar Aas Oslo katedralskoles historie 1153–1800 Skolen og tiden Redaksjon: Anders Langangen, Vibeke Roggen, Hilde Sejersted, Tore Haakensen og Arild Eilif Aasbo Oslo 2016 (Skolens våpenskjold i mindre utførelse) ©Stiftelsen Oslo katedralskole, Oslo 2016 Redaksjon: Anders Langangen, Vibeke Roggen, Hilde Sejersted,Tore Haakensen og Arild Eilif Aasbo Boken er satt med Palatino Linotype 11 pkt/13 pkt Grafisk tilrettelegging: Bokproduksjon SA/Ove Olsen ISBN 978-82-992654-7-8 (e-bok) Redaksjonens forord På Oslo katedralskole lå det et 500 sider langt manuskript fra 1930-tallet. Det var et utkast til Oslo katedralskoles historie fra ca. 1150 til omkring 1800, skrevet av Einar Aas (1857–1941). Den som tok initiativet til å gjøre noe med dette var Anders Langangen, pensjonert lektor ved skolen, og gjennom mange år en drivkraft for beskjeftigelse med skolens historie. I 2012 fikk han med seg to tidligere kolleger, Hilde Sejersted og Tore Haakensen, samt Arild Eilif Aasbo, et barnebarn av Aas. Gjen- nom to år arbeidet denne gruppen med å omforme håndskrif- tet til en digital versjon, og, ettersom arbeidet skred frem: med å gjennomgå teksten. Det var på dette tidspunktet at Vibeke Roggen ble invitert med i redaksjonen; hun er førsteamanu- ensis i latin ved Universitetet i Oslo med forskningsarbeider relatert til Oslo katedralskole i eldre tid. Manuskriptet som redaksjonen har hatt som utgangspunkt for sitt arbeid, bærer preg av å være et utkast. Det er tydelig mindre gjennomarbeidet enn Aas’ publiserte skolehistorier: Stavanger katedralskoles historie 1243–1826 (1925) og Kristi- ansands katedralskoles historie 1642–1908 (1932), foruten Kristia- nia katedralskoles historie i det nittende århundre (1935). -

Mapping European Security After Kosovo

VANHAMME.D-J 18/11/04 3:16 pm Page 1 Mapping European security after Kosovo Mapping European Mapping European security after Kosovo van Ham, Medvedev edited by Peter van Ham – eds and Sergei Medvedev Mapping European security after Kosovo Allie Mapping European security after Kosovo edited by Peter van Ham and Sergei Medvedev Manchester University Press Manchester and New York distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave Copyright © Manchester University Press 2002 While copyright in the volume as a whole is vested in Manchester University Press, copyright in individual chapters belongs to their respective authors, and no chapter may be reproduced wholly or in part without the express permission in writing of both author and publisher. Published by Manchester University Press Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9NR, UK and Room 400, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk Distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA Distributed exclusively in Canada by UBC Press, University of British Columbia, 2029 West Mall, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z2 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for ISBN 0 7190 6240 3 hardback First published 2002 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Typeset in Times by Graphicraft Limited, Hong Kong Printed in Great Britain by Biddles Ltd, Guildford and King’s Lynn Contents List of figures page viii