Representations of Eastern Europe in NATO and EU Expansion Jason N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Estonia – the 'Baltic Tiger'

Markets & Regions ESTONIA | OVERVIEW Estonia – the ‘baltic tiger’ LOCATED AT THE TOP OF EUROPE AND BORDERING RUSSIA, ESTONIA IS A SMALL COUNTRY WITH BIG AMBITIONS. THE MARINE INDUSTRY IS CURRENTLY SHOWING THE LARGEST GROWTH WITHIN A HIGH-INCOME ECONOMY WORDS: JAKE KAVANAGH government-issued digital identity that allows entrepreneurs around the world to set up and run a location-independent business’. So far, 15,000 individuals have registered under this scheme. Estonian citizens enjoy a high level of civil liberty and press freedom, with very few economic restraints. The marine industry has played a key role in the country’s success, with two-thirds of production in the workboat sector and the remaining third in leisure. Around 80% of all marine products are exported, and Estonia is also building its first custom superyacht at the inland yard of Ridas Yachts. IBI was given an ‘overview’ tour of 11 leisure yards and businesses out of a total of around 200 marine enterprises during a visit in June 2017, and saw for ourselves just how advanced the marine industry has Many former factories have been re- become. The quality of manufacturing easily equals tasked for boatbuilding, with rental costs rival EU countries, and is aided by the full use of around one-third of those in Western cities computer-aided design and a high concentration of modern 5-axis CNC machines. stonia may only be a country of just 1.3 million “We have a very high standard of education,” people in a footprint slightly larger than explains Anni Hartikainen of the Small Craft E Denmark, but the population is outward Competence Centre, a campus of Tallinn University. -

The Roman Province of Judea: a Historical Overview

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 36 Issue 3 Article 23 7-1-1996 The Roman Province of Judea: A Historical Overview John F. Hall Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Part of the Mormon Studies Commons, and the Religious Education Commons Recommended Citation Hall, John F. (1996) "The Roman Province of Judea: A Historical Overview," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 36 : Iss. 3 , Article 23. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol36/iss3/23 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hall: The Roman Province of Judea: A Historical Overview p d tffieffiAinelixnealxAIX romansixulalealliki glnfin ns i u1uaihiihlanilni judeatairstfsuuctfa Published by BYU ScholarsArchive, 1996 1 BYU Studies Quarterly, Vol. 36, Iss. 3 [1996], Art. 23 the roman province judeaofiudeaofofjudea A historical overview john E hall the comingcoining of rome to judea romes acquisition ofofjudeajudea and subsequent involvement in the affairs of that long troubled area came about in largely indirect fashion for centuries judea had been under the control of the hel- lenilenisticstic greek monarchy centered in syria and known as the seleu- cid empire one of the successor states to the far greater empire of alexander the great who conquered the vast reaches of the persian empire toward the end of the fourth century -

Russian Foreign Policy and National Identity

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Senior Honors Theses Undergraduate Showcase 12-2017 Russian Foreign Policy and National Identity Monica Hanson-Green University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/honors_theses Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Hanson-Green, Monica, "Russian Foreign Policy and National Identity" (2017). Senior Honors Theses. 99. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/honors_theses/99 This Honors Thesis-Restricted is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Honors Thesis-Restricted in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Honors Thesis-Restricted has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RUSSIAN FOREIGN POLICY AND NATIONAL IDENTITY An Honors Thesis Presented to the Program of International Studies of the University of New Orleans In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts, with University High Honors and Honors in International Studies By Monica Hanson-Green December 2017 Advised by Dr. Michael Huelshoff ii Table of Contents -

European Culture

EUROPEAN CULTURE SIMEON IGNATOV - 9-TH GRADE FOREIGN LANGUAGE SCHOOL PLEVEN, BULGARIA DEFINITION • The culture of Europe is rooted in the art, architecture, film, different types of music, economic, literature, and philosophy that originated from the continent of Europe. European culture is largely rooted in what is often referred to as its "common cultural heritage”. • Because of the great number of perspectives which can be taken on the subject, it is impossible to form a single, all-embracing conception of European culture. Nonetheless, there are core elements which are generally agreed upon as forming the cultural foundation of modern Europe. One list of these elements given by K. Bochmann includes:] PREHISTORIC ART • Surviving European prehistoric art mainly comprises sculpture and rock art. It includes the oldest known representation of the human body, the Venus of Hohle Fel, dating from 40,000-35,000 BC, found in Schelklingen, Germany and the Löwenmensch figurine, from about 30,000 BC, the oldest undisputed piece of figurative art. The Swimming Reindeer of about 11,000 BCE is among the finest Magdalenian carvings in bone or antler of animals in the art of the Upper Paleolithic. At the beginning of the Mesolithic in Europe figurative sculpture greatly reduced, and remained a less common element in art than relief decoration of practical objects until the Roman period, despite some works such as the Gundestrup cauldron from the European Iron Age and the Bronze Age Trundholm sun chariot. MEDIEVAL ART • Medieval art can be broadly categorised into the Byzantine art of the Eastern Roman Empire, and the Gothic art that emerged in Western Europe over the same period.Byzantine art was strongly influenced by its classical heritage, but distinguished itself by the development of a new, abstract, aesthetic, marked by anti-naturalism and a favour for symbolism. -

How the Kremlin Weaponizes Information, Culture and Money by Peter Pomerantsev and Michael Weiss

The Menace of Unreality: How the Kremlin Weaponizes Information, Culture and Money by Peter Pomerantsev and Michael Weiss A Special Report presented by The Interpreter, a project of the Institute of Modern Russia imrussia.org interpretermag.com The Institute of Modern Russia (IMR) is a nonprofit, nonpartisan public policy organization—a think tank based in New York. IMR’s mission is to foster democratic and economic development in Russia through research, advocacy, public events, and grant-making. We are committed to strengthening respect for human rights, the rule of law, and civil society in Russia. Our goal is to promote a principles- based approach to US-Russia relations and Russia’s integration into the community of democracies. The Interpreter is a daily online journal dedicated primarily to translating media from the Russian press and blogosphere into English and reporting on events inside Russia and in countries directly impacted by Russia’s foreign policy. Conceived as a kind of “Inopressa in reverse,” The Interpreter aspires to dismantle the language barrier that separates journalists, Russia analysts, policymakers, diplomats and interested laymen in the English-speaking world from the debates, scandals, intrigues and political developments taking place in the Russian Federation. CONTENTS Introductions ...................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ........................................................... 6 Background ........................................................................ -

The Rhetoric of the “March of Independence” in Poland (2010

ARTICLES WIELOKULTUROWość… Politeja No. 4(61), 2019, p. 149-166 https://doi.org/10.12797/Politeja.16.2019.61.09 Elżbieta WIącEK Jagiellonian University in Kraków [email protected] ThE RhETORIC OF THE “MARCH OF INDEPENDENCE” IN POLAND (2010-2017) AS THE ANswER FOR THE POLICY OF MULTICULTURALIsm IN EU AND THE REFUGEE CRISIS ABSTRact In 2010, Polish far-right nationalist groups hit upon the idea of establishing one common nationwide march to celebrate National Independence Day in Poland. Since then, the participants have manifested their attachment to Polish tradi- tion, and their anti-multicultural attitude. Much of the debate about multicul- turalism and the emergence of conflictual and socially divisive ethnic groupings has addressed ethical concerns. In contrast, this paper focuses on the semiotic and structural level of the problem. Key words: March of Independence, nationalism, refugees, values, patriotism 150 Elżbieta Wiącek POLITEJA 4(61)/2019 fter Poland’s accession to the European Union in May 2004 new laws on national, Aethnic and linguistic minorities were accepted and put into practice.1 However, cur- rent Polish multiculturalism is different from that of multi-ethnic or immigrant societies such as the UK. Indeed, multiculturalism in contemporary Poland can be seen as a his- torical phenomenon, one linked to the long-lasting ‘folklorisation’ of diversity. For in- stance, although ‘multicultural’ festivals are organised in cities, towns and in borderland regions, all of them refer to past ‘multi-ethnic’ or religiously diversified life. Tolerance is evoked as an old Polish historical tradition. The historical Commonwealth of Poland and Lithuania (1385-1795) was in itself diverse linguistically, ethnically and religiously, and it also welcomed various ethnic and religious minorities, especially Jews. -

Brief Analysis of the Medieval and Modern European Cultures

www.ccsenet.org/ass Asian Social Science Vol. 7, No. 3; March 2011 Brief Analysis of the Medieval and Modern European Cultures Hongli Shi Teaching Affairs Office, Department of Secondary School, South Campus, Dezhou University No. 67 Youth League Road, Dezhou 253000, Shandong, China E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Irrationality of the medieval culture in the Dark Ages gave birth to the bright modern European culture and the modern European culture had more rational, scientific, secular and individualist characteristics. The progress in the culture meanwhile promoted the progresses in other aspects of politics, economy and social life, etc. Keywords: Middle Ages, Christianity, Promote In the history of the European civilization, modern European civilization is undoubtedly one of the most magnificent stages. If we want to uncover the veil of modern culture, it might be well to compare the modern European culture and the medieval European culture. And we will easily find that they are essentially the collision of rational cognition and irrational cognition. 1. The medieval culture with irrational cognition "Irrationalism" means that the medieval Europe was controlled by the backward and unplanned cultural tradition, resulting in unclear boundaries between man and god, reality and otherworldliness. Examining the medieval culture, we may find that it emphasized too much the religious orison, heroism, romanticism and scholastic philosophy. All these show that the medieval European culture is lack of rational spirit. 1.1 Religion was indispensable to human life and Christianity was undoubtedly in a dominant place in the Middle Ages. The religion of Christianity has two sources. One is that the ancient Greek philosophical heritage, especially the new Platonism and Stoicism, is its ideological root. -

Corruption in Russia: Reasons for the Growth

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 336 5th International Conference on Social Science and Higher Education (ICSSHE 19) Corruption in Russia: Reasons for the Growth V.V. Moiseev I. V. Goncharova Belgorod State Technological University named after V.G. Orel State University named after I.S. Turgenev Shukhov Orel, 302026, Russia Belgorod, 308012, Russia [email protected] G. S. Chuvardin Orel State University named after I.S. Turgenev Orel, 302026, Russia Abstract—The scale of increased corruption in Russia is such Council did not bring tangible results, since its composition that it began to threaten the national security of our country. was practically no longer assembled, and soon it was abolished, This conclusion belongs not only to the authors of this article, without becoming a viable political institution. who have been conducting research in this field for a long time, but also to the head of state, who recently signed a special Pursuant to the President’s instructions, a special directive on national security. The main goal of the authors of the commission of the State Duma was created to prepare article was to show why corruption in Russia acquired such a proposals for amending existing legislation in order to enhance wide scope, what reasons contributed to its growth in 2000-2019. legal mechanisms to combat corruption. However, a legal In accordance with the purpose of the study, the following main mechanism to combat corruption was not created in 2000-2008: questions were identified: 1) showing the increase in the scale and the State Duma twice passed a law on combating corruption, level of corruption in the country in 2000-2019; 2) to analyze the and both times, President Vladimir Putin rejected it, using the causes of weak anti-corruption in Russia; 3) showing the role of right of veto. -

TU1206-WG1-014 TU1206 COST Sub-Urban WG1 Report S

Sub-Urban COST is supported by the EU Framework Programme Horizon 2020 Vienna TU1206-WG1-014 TU1206 COST Sub-Urban WG1 Report S. Pfl eiderer, G. Götzl & S.Geier Sub-Urban COST is supported by the EU Framework Programme Horizon 2020 COST TU1206 Sub-Urban Report TU1206-WG1-14 Published March 2016 Authors: S. Pfleiderer, G. Götzl & S.Geier Editors: Ola M. Sæther and Achim A. Beylich (NGU) Layout: Guri V. Ganerød (NGU) COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology) is a pan-European intergovernmental framework. Its mission is to enable break-through scientific and technological developments leading to new concepts and products and thereby contribute to strengthening Europe’s research and innovation capacities. It allows researchers, engineers and scholars to jointly develop their own ideas and take new initiatives across all fields of science and technology, while promoting multi- and interdisciplinary approaches. COST aims at fostering a better integration of less research intensive countries to the knowledge hubs of the European Research Area. The COST Association, an International not-for-profit Association under Belgian Law, integrates all management, governing and administrative functions necessary for the operation of the framework. The COST Association has currently 36 Member Countries. www.cost.eu www.sub-urban.eu www.cost.eu Acknowledgements “This report is based upon work from COST Action TU1206 Sub-Urban, supported by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology). Sub-Urban is a European network to improve understanding and the use of the ground beneath our cities (www.sub-urban.eu)”. Geological Survey of Austria Vienna Municipal Department for Energy Planning Content 1. -

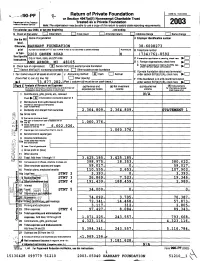

'90-PF ~. Return of Private Foundation

OMB No 1545- 005 2 ;'90-PF ~. Return of Private Foundation or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Department of the Treasury Treated as a Private Foundation Internal Revenue Service Note : The organization may be able to use a copy o/ this return to satisfy state reporting requirements. 2003 For calendar year 2003. or endin Name of organization Employer identification number Use the IRS label . Otherwise, ARHART FOUNDATION J1o-v11 .1161oZ print Numbs and sheet (a P O box numbs d meal is not delivered to street address) RoorNeurte g Telephone number or type. 2200 GREEN ROAD I i ay i i vi-o» .6 See Specific If exemption application is pending, check hers Instructions . City or town, state, and ZIP code 0 1 . Foreign organizations, check here 2, Forsi~ organizations meeting the 85% test, , H Check type of organization : LM Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation check here and attach computation Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust E:J Other taxable private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method : X Cash [ Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here " D (from Part It, Col. (c), tine 16) 0 Other (specify) F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination $ 7 3 8 7 7 2 8 2 . (Part l, column (d) must be on cash basi, under section 507 b 1 B check here pad I Analysis of Revenue and Expenses I Revenue and (C) Adjusted net (d) Disbursements (The total of amounts in columns (b), (c), end (d) may not 1~) (b) Net investment for charitable -

Ancient Rome

Ancient Rome William E. Dunstan ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD PUBLISHERS, INC. Lanham • Boulder • New York • Toronto • Plymouth, UK ................. 17856$ $$FM 09-09-10 09:17:21 PS PAGE iii Published by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 http://www.rowmanlittlefield.com Estover Road, Plymouth PL6 7PY, United Kingdom Copyright ᭧ 2011 by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. All maps by Bill Nelson. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. The cover image shows a marble bust of the nymph Clytie; for more information, see figure 22.17 on p. 370. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dunstan, William E. Ancient Rome / William E. Dunstan. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7425-6832-7 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-7425-6833-4 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-7425-6834-1 (electronic) 1. Rome—Civilization. 2. Rome—History—Empire, 30 B.C.–476 A.D. 3. Rome—Politics and government—30 B.C.–476 A.D. I. Title. DG77.D86 2010 937Ј.06—dc22 2010016225 ⅜ϱ ீThe paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/ NISO Z39.48–1992. Printed in the United States of America ................ -

Annex 1A Proposals for New Pilot Projects

Ref. Ares(2017)3358018 - 04/07/2017 Annex 1a Proposals for New Pilot Projects A = PP/PA could be implemented as suggested by the Parliament; B = PP/PA might under certain conditions be fully or partially implementable but the project would need to be re-designed (it could be the case if part of the suggested action is already covered by a legal base); or more information might be needed before the Commission can assess the proposed project; C = PP/PA is fully covered by a legal base or the ideas are otherwise being addressed; D = PP/PA cannot be implemented or similar actions have already been carried out in the past. N° EP Proposal DG Commission Assessment Category Heading 1a 1 European Fund for FISMA The project might be partially implementable if changes are implemented to its scope and proposed timing B Crowfunded due, inter alia, to avoid of overlaps with a proposal on Crowdfunding to be launched in the course of 2018. Investments Proposed by Maria However, as a new related commitment was adopted (on 08/06/2017) in the CMU Mid-Term Review, the Spyraki project could be used to identify best practices in supply chain finance (e.g. invoice trading). Many start-ups and innovative SMEs are under-collateralised and fail due to short-term cash flow problems, while having a sustainable business model in the long-term. The amount needed for such a project should be reduced down to 500.000€ (250.000€). Given the clear commonalities between n°1 and n°107, the EC will consider the possibility of a joint implementation by giving a specific focus on SMEs' access to finance, should more that one of those PP be finally adopted by the EP.