The Reception of Danish Science Fiction in the United States Kristine J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

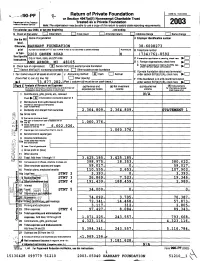

'90-PF ~. Return of Private Foundation

OMB No 1545- 005 2 ;'90-PF ~. Return of Private Foundation or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Department of the Treasury Treated as a Private Foundation Internal Revenue Service Note : The organization may be able to use a copy o/ this return to satisfy state reporting requirements. 2003 For calendar year 2003. or endin Name of organization Employer identification number Use the IRS label . Otherwise, ARHART FOUNDATION J1o-v11 .1161oZ print Numbs and sheet (a P O box numbs d meal is not delivered to street address) RoorNeurte g Telephone number or type. 2200 GREEN ROAD I i ay i i vi-o» .6 See Specific If exemption application is pending, check hers Instructions . City or town, state, and ZIP code 0 1 . Foreign organizations, check here 2, Forsi~ organizations meeting the 85% test, , H Check type of organization : LM Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation check here and attach computation Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust E:J Other taxable private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method : X Cash [ Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here " D (from Part It, Col. (c), tine 16) 0 Other (specify) F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination $ 7 3 8 7 7 2 8 2 . (Part l, column (d) must be on cash basi, under section 507 b 1 B check here pad I Analysis of Revenue and Expenses I Revenue and (C) Adjusted net (d) Disbursements (The total of amounts in columns (b), (c), end (d) may not 1~) (b) Net investment for charitable -

Constructing Danish Identity Transcultural Adaptation in Peter

Coversheet This is the accepted manuscript (post-print version) of the article. Contentwise, the post-print version is identical to the final published version, but there may be differences in typography and layout. How to cite this publication Please cite the final published version: Stephan, M. (2016). Constructing Danish Identity: Transcultural Adaptation in Peter Høeg’s The History of Danish Dreams. Scandinavian Studies 88(2), 182-202. University of Illinois Press. Publication metadata Title: Constructing Danish Identity: Transcultural Adaptation in Peter Høeg’s The History of Danish Dreams Author(s): Matthias Stephan Journal: Scandinavian Studies DOI/Link: https://muse.jhu.edu/article/634084/summary Document version: Accepted manuscript [post-print] Accepted date: Jan 22, 2016 General Rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. This coversheet template is made available by AU Library Version 1.0, October 2016 Constructing Danish Identity: Transcultural Adaptation in Peter Høeg’s The History of Danish Dreams Matthias Stephan Århus University his paper discusses the Danish novel Forestilling om det tyvende århundrede, published in 1988, or perhaps more accurately, the T1995 American translation of the novel, The History of Danish Dreams. -

Doorway to Devotion: Recovering the Christian Nature of the Gosforth Cross

religions Article Doorway to Devotion: Recovering the Christian Nature of the Gosforth Cross Amanda Doviak Department of History of Art, University of York, York YO10 5DD, UK; [email protected] Abstract: The carved figural program of the tenth-century Gosforth Cross (Cumbria) has long been considered to depict Norse mythological episodes, leaving the potential Christian iconographic import of its Crucifixion carving underexplored. The scheme is analyzed here using earlier ex- egetical texts and sculptural precedents to explain the function of the frame surrounding Christ, by demonstrating how icons were viewed and understood in Anglo-Saxon England. The frame, signifying the iconic nature of the Crucifixion image, was intended to elicit the viewer’s compunction, contemplation and, subsequently, prayer, by facilitating a collapse of time and space that assim- ilates the historical event of the Crucifixion, the viewer’s present and the Parousia. Further, the arrangement of the Gosforth Crucifixion invokes theological concerns associated with the veneration of the cross, which were expressed in contemporary liturgical ceremonies and remained relevant within the tenth-century Anglo-Scandinavian context of the monument. In turn, understanding of the concerns underpinning this image enable potential Christian symbolic significances to be suggested for the remainder of the carvings on the cross-shaft, demonstrating that the iconographic program was selected with the intention of communicating, through multivalent frames of reference, the significance of Christ’s Crucifixion as the catalyst for the Second Coming. Keywords: sculpture; art history; archaeology; early medieval; Anglo-Scandinavian; Vikings; iconog- raphy Citation: Doviak, Amanda. 2021. Doorway to Devotion: Recovering the Christian Nature of the Gosforth Cross. -

“To Establish a Free and Open Forum”: a Memoir of the Founding of the Grundtvig Society

“To establish a free and open forum”: A memoir of the founding of the Grundtvig Society By S. A. J. Bradley With the passing of William Michelsen (b. 1913) in October 2001 died the last of the founding fathers of Grundtvig-Selskabet af 8. september 1947 [The Grundtvig Society of 8 September 1947] and of Grundtvig- Studier [Grundtvig Studies] the Society’s year-book.1 It was an appropriate time to recall, indeed to honour, the vision and the enthusiasm of that small group of Grundtvig-scholars - some very reverend and others just a touch irreverent, from several different academic disciplines and callings but all linked by their active interest in Grundtvig - who gathered in the bishop’s residence at Ribe in September 1947, to see what might come out of a cross-disciplinary discussion of their common subject. Only two years after the trauma of world war and the German occupation of Denmark, and amid all the post-war uncertainties, they talked of Grundtvig through the autumn night until, as the clock struck midnight and heralded Grundtvig’s birthday, 8 September, they formally resolved to establish a society that would serve as a free and open forum for the advancement of Grundtvig studies. The biographies of the principal names involved - who were not only theologians and educators but also historians and, conspicuously, literary scholars concerned with Grundtvig the poet - and the story of this post-war burgeoning of the scholarly reevaluation of Grundtvig’s achievements, legacy and significance, form a remarkable testimony to the integration of the Grundtvig inheritance in the mainstream of Danish life in almost all its departments, both before and after the watershed of the Second World War. -

SCANDINAVIAN LANGUAGES and LITERATURES Sara De Kundo 10 and Tom Kilton; July 1984

S 1-1 SCANDINAVIAN LANGUAGES AND LITERATURES Sara de Kundo 10 and Tom Kilton; July 1984 I. DESCRIPTION A. Purpose: To support the instructional and research programs of the Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures involving the literature and language studies of Old Norse/Icelandic, runes, and the historical and current literatures and languages of Iceland, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and the Faeroe Islands. B. Hist0tY of Collection: In the early 20th century, Scandinavian studies were taught in the English Department. The collections were built up significantly by prominent professors, notably Henning Larsen and George Flom. The George Flom Library of over 2,000 valuable items was donated in 1941, and the Henning Larsen collection was purchased in 1971. Since 1959 Scandinavian language, literature and cultural studies have been offered regularly through the Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures. C. Estimate of Holdinis: 23,475 volumes. D. State. Reiional. and National Importance: The Scandinavian collections at Illinois are considered by most scholars to be outstanding and to rank among the top ten North American libraries with collections in these areas. E. Unit Responsible for Collectini: Modern Languages and Linguistics Library. F. Location of Materials: Reference works and a small core collection are held in Modern Languages and Linguistics Library. The majority of materials are in the Bookstacks , but many are in the Reference Room, the Rare Book and Special Collections Library, and the Undergraduate Library. G. Citations of Works Describini the Collection: Downs, pp. 113, 206. Major, p. 59. II. GENERAL COLLECTION GUIDELINES A. Lan&Ua&es: Primarily Old Norse/Icelandic, Danish, Norwegian, Swedish, and English, with selective acquisition of translations of primary source mate~ials as well as secondary criticism in other Western European languages. -

Mapping European Security After Kosovo

VANHAMME.D-J 18/11/04 3:16 pm Page 1 Mapping European security after Kosovo Mapping European Mapping European security after Kosovo van Ham, Medvedev edited by Peter van Ham – eds and Sergei Medvedev Mapping European security after Kosovo Allie Mapping European security after Kosovo edited by Peter van Ham and Sergei Medvedev Manchester University Press Manchester and New York distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave Copyright © Manchester University Press 2002 While copyright in the volume as a whole is vested in Manchester University Press, copyright in individual chapters belongs to their respective authors, and no chapter may be reproduced wholly or in part without the express permission in writing of both author and publisher. Published by Manchester University Press Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9NR, UK and Room 400, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk Distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA Distributed exclusively in Canada by UBC Press, University of British Columbia, 2029 West Mall, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z2 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for ISBN 0 7190 6240 3 hardback First published 2002 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Typeset in Times by Graphicraft Limited, Hong Kong Printed in Great Britain by Biddles Ltd, Guildford and King’s Lynn Contents List of figures page viii -

Danish Law, Part II

University of Miami Law Review Volume 5 Number 2 Article 3 2-1-1951 Danish Law, Part II Lester B. Orfield Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr Recommended Citation Lester B. Orfield, Danish Law, Part II, 5 U. Miami L. Rev. 197 (1951) Available at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr/vol5/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DANISH LAW DANISH LAW LESTER B. ORFIELD PART II* LOCAL GOVERNMENT In 1841 local government was reformed by introducing parish councils to which the peasants elected some representatives. 233 In turn the parish councils elected members of the county councils. The pastors were no longer to be chairmen of the parish councils, but continued to be members ex officio. The right to vote was extended to owners of but 1.4 acres. The councils were created to deal with school matters and poor relief; but road maintenance, public health, business and industrial licenses, and liquor licenses were also within their province. The right to vote in local elections was long narrowly restricted. Under legislation of 1837 the six largest cities other than Copenhagen chose coun- cilmen on a property basis permitting only seven per cent of the population to vote. Early in the nineteenth century rural communities began to vote for poor law and school officials. -

Danish Culture

DANISH CULTURE DANISH CULTURE IS RELAXED AND COLLECTIVE VALUES ARE BUILT ON TRUST, SECURITY AND COOPERATION. VIEWS ON RELIGION AND POLITICS ARE RATHER LIBERAL, AND HUMOUR IS DEEPLY ROOTED IN DANES. THE SUPPORTIVE DANISH WELFARE STATE GRANTS EQUAL OPPORTUNITIES FOR ALL, THUS PROVIDING A STRONG FEELING OF SECURITY AND BELONGING. WHAT ARE DANES LIKE? central part of Danish culture. Comedians unteer work or simply donate money for Generally, Danes have very liberal views make fun of famous people, and even the charities. Moreover, Danes are increasing- on sex, religion and politics compared royal family, to their audience’s amuse- ly concerned about global issues, so they to most Europeans. However, they are ment. Irony is an important part of Danish buy fair trade and environmentally friend- also rule-bound and complying with the humour and conversation, which may take ly products and recycle more than the Eu- norms is important and appreciated. some time getting used to for interna- ropean average. Wealth in Denmark is equally distribut- tionals. Danes may not initiate small talk ed, so there are relatively few billionaires with strangers themselves, but Danes are THE “HYGGE” CONCEPT or really poor people. Attitudes towards polite and will engage in conversation if When foreigners are asked to describe success and money are humble, and con- they are spoken to. Danish culture, a special concept comes sequently bragging is unusual and socially to mind: “hygge”. Linked to cosiness and unacceptable. Most Danes are outspoken SOCIAL AND CULTURAL VALUES warmth, “hygge” is normally associated and direct; they are used to having open Altruism is a core value in Denmark. -

Representations of Eastern Europe in NATO and EU Expansion Jason N

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2003 European Re-Union: Representations of Eastern Europe in NATO and EU Expansion Jason N. Dittmer Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES EUROPEAN RE-UNION: REPRESENTATIONS OF EASTERN EUROPE IN NATO AND EU EXPANSION By JASON N. DITTMER A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Geography In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2003 The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Jason N. Dittmer defended on March 25, 2003 ______________________________ Patrick O’Sullivan Professor Directing Dissertation Jonathan Grant Outside Committee Member ______________________________ Jonathan Leib Committee Member ______________________________ Jan Kodras Committee Member Approved: _____________________________ Barney Warf, Chair, Department of Geography The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above committee members. ii This dissertation is dedicated to my mother, who always made her children’s education a priority and gave up many of her own personal satisfactions to make sure that we were in the best schools with the best teachers. Thanks Mom… This dissertation is also dedicated to Karl Fiebelkorn, who would be mortified to know that something so academic as this dissertation was dedicated to him. But think of it this way Karl – this is just to tide you over until I can dedicate to you my magnum opus: “I See How It Is”: Reflections on Brotherhood. You are missed, Karl. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the assistance of a great many of my colleagues and friends, who have all influenced my thoughts on these matters (and many others). -

Danish Nobel Laureates in Literature with Special Emphasis on Johannes V

The Bridge Volume 29 Number 2 Article 31 2006 Danish Nobel Laureates in Literature With Special Emphasis on Johannes V. Jensen Erik M. Christensen Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/thebridge Part of the European History Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, and the Regional Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Christensen, Erik M. (2006) "Danish Nobel Laureates in Literature With Special Emphasis on Johannes V. Jensen," The Bridge: Vol. 29 : No. 2 , Article 31. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/thebridge/vol29/iss2/31 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Bridge by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Danish Nobel Laureates in Literature With Special Emphasis on Johannes V. Jensen by Erik M. Christensen Religion, Philosophy, and Art are related. Sometimes more than other. They are so much in family, in fact, that they are able to become one. This may even happen without being intended or even realized, but we also have, in Western civilization, instances where the artist very clearly meant his work to represent a unity of Religion, Philosophy, and Art. The greatest known instance of this is, of course, Dante Alighieri's poem La Divina Commedia (ca. 1307- 1320), the story of his wandering through Purgatory, down to Hell, and up to Paradise where his ideal love for Beatrice allows him to unite with God. If you are the reader Dante intended you to be, you will at the end of The Divine Comedy be convinced that Religion, Philosophy, and Art are very much in family and certainly able to become one. -

Classical Liberalism and Modern Political Economy in Denmark

Classical liberalism and modern political economy in Denmark Kurrild-Klitgaard, Peter Published in: Econ Journal Watch Publication date: 2015 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (APA): Kurrild-Klitgaard, P. (2015). Classical liberalism and modern political economy in Denmark. Econ Journal Watch, 12(3), 400-431. https://econjwatch.org/articles/classical-liberalism-and-modern-political-economy-in-denmark Download date: 01. okt.. 2021 Discuss this article at Journaltalk: http://journaltalk.net/articles/5895 ECON JOURNAL WATCH 12(3) September 2015: 400–431 Classical Liberalism and Modern Political Economy in Denmark Peter Kurrild-Klitgaard1 LINK TO ABSTRACT Over the last century, classical liberalism has not had a strong presence in Danish social science, including economics. Several studies have shown that social scientists in Denmark tilt leftwards. In a 1995–96 survey only 7 percent of political scientists and 3 percent of sociologists said they had voted for (classical-)liberal or conservative parties, whereas support for socialist parties among the same groups were 51 percent and 78 percent. Lawyers and economists were more evenly split between left and right, but even there the left dominated: 31 percent and 25 percent for at least nominally free-market friendly parties and 38 percent and 36 percent for socialist parties.2 Very vocal free-market voices in academia have been rare. This marginalization of liberalism was not always the case. Denmark was among the first countries to see publication of a translation of Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations (Smith 1779/1776; see Rae 1895, ch. 24; Kurrild-Klitgaard 1998; 2004). -

Denmark,Liberalism

Discuss this article at Journaltalk: http://journaltalk.net/articles/5895 ECON JOURNAL WATCH 12(3) September 2015: 400–431 Classical Liberalism and Modern Political Economy in Denmark Peter Kurrild-Klitgaard1 LINK TO ABSTRACT Over the last century, classical liberalism has not had a strong presence in Danish social science, including economics. Several studies have shown that social scientists in Denmark tilt leftwards. In a 1995–96 survey only 7 percent of political scientists and 3 percent of sociologists said they had voted for (classical-)liberal or conservative parties, whereas support for socialist parties among the same groups were 51 percent and 78 percent. Lawyers and economists were more evenly split between left and right, but even there the left dominated: 31 percent and 25 percent for at least nominally free-market friendly parties and 38 percent and 36 percent for socialist parties.2 Very vocal free-market voices in academia have been rare. This marginalization of liberalism was not always the case. Denmark was among the first countries to see publication of a translation of Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations (Smith 1779/1776; see Rae 1895, ch. 24; Kurrild-Klitgaard 1998; 2004). Throughout the 19th century the emerging field of economics at the University of Copenhagen was visibly inspired not only by Smith and David Ricardo but also the “Manchester liberals” and French classical liberal economists Jean Baptiste Say and Frédéric Bastiat, of whose works timely translations were made. The university had professors of economics who today would be termed classical liberals, e.g., Oluf Christian Olufsen (1764–1827), Christian G.