A Study of Transience in South Auckland Primary Schools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROUTE 309 & 309X

ROUTE 309 & 309x - MANGERE TOWN CENTRE, FAVONA, ONEHUNGA, PAH RD, CITY t W t S S a S t l t n y l a o t M e S c s e m l yl e St Marys a g u r r a S A y a t H s e Bay Britomart Jervois Rd R B t d S t t Herne Bay e S Cu w S s Mission sha t to Coxs Bay St Marys an r m F n s Q e S u A t a C College e y St Bay ol lb e n Okahu Bay le Vi A u z g cto a T e Hill W r Q a e ia c m lle S t t A a sl S k Ta ey v m s i a r e D St d e ki Rd e n D a Parnell v d c r P t r C A o n S d En Ponsonby o R ok i e t M r h t St T n s i e n W n S P St Pauls li t k s k a n S Auckland t College o n y t Mission Bay a o D i r A n r s o k n F l S University t a t o Westmere e s r S m b S a a T N n y y n ob t l r S e H D e l R u t r AUT n n e P Grey Lynn d b e a e a d G p v u t c t e A S r R a n S i s Q n r H y a n V e s e Ngap r i e e AGGS d l p C m G l v t n i o a R a A r d R R i d R t o R mon S e te a d ch n d v n ou d s K d o t m A m e i u p ape y R s A s o h Rd n v h H a S e e p e g t n o n e d h R ra p t o K a e t t a a t S l K S S f P eo Auckland St t a M e n r v N e Hobson Bay Orakei e G City Hospital A d e n R d u o r R w Pa O e Q rk ld ms m h R M Surre ia t t r r d d y Cr l m r e ill il u o o D R R r n n p 1 d W C N o l Selwyn t p l Kepa Rd n U a n Rd e Orakei College re i rn Ay k Grafton a r G 16 c P St Car M lton 309 Go d n re e R hore Rd R t d S v a S I d i i B A u 309x Grafton R e T o Baradene a Rd k reat North Arch Hill Newmarket i G n d r a K College r d hy n o b t Meadowbank St Peters e a O l c D Mt Eden r r 16 i S g Pa t U d r t College s V n s i p d -

PRESENT and FUTURE TRENDS 2.1 the Form of the City I 2.2 Growth of the City 2.3 the Existing Population

I I I PART 2 THE CITY: PRESENT AND FUTURE TRENDS 2.1 The Form of the City I 2.2 Growth of the City 2.3 The Existing Population I 2.4 Future Population Growth I 2.5 Employment 2.6 Building Development and Demand I 2.7 Energy Conservation and Land Use 2.8 Rural Land Use I 2.9 Future Urban Growth I 2.10 Land presently zoned for Urban Uses I I I I I I I I I I I I I PART 2 THE CITY: PRESENT AND FUTURE TRENDS I I 2.1 THE FORM OF THE CITY Manukau City had a population in March 1981 of 159,362. Its land area of over 600 square kilometres dominates the southern part of the Auckland Region. I The territorial integrity of the district, which stretches from the edge of the Auckland isthmus in the north to the Hunua ranges in the South, is interrupted only by the local authority enclaves of Papatoetoe City and 0tahuhu and Howick I Boroughs. The Manukau City Centre, 25 km south of Auckland Centre, is the natural geographical focus of the city's urban area . When fully developed the urban area I will stretch out from the Centre southwards to Manurewa and Takanini, northeastwards to Otara and Pakuranga and northwest to Mangere. Two-thirds of the City's land area is in rural use, ranging from dairy and town milk supply I units to pastoral farming, horticulture and forestry . A distinctive feature of the district is its extensive coastline of 320 km. -

THE CHURCH by the AIRPORT Westney Road Methodist Church

The Church by the Airport by R. Waugh THE CHURCH BY THE AIRPORT Westney Road Methodist Church, Mangere - Richard WAUGH Most Aucklanders have driven past it, but few have ever been inside it! The small Westney Road Chapel on George Bolt Drive is the first Church that people see as they leave Auckland International Airport. Built as a pioneer rural chapel in 1856 it is today one of the oldest surviving Methodist Churches in the Auckland area. Its future is somewhat precarious as there are plans for airport extensions with a second runway which would necessitate removal of the Church building and cemetery. Part of the Manukau North Parish since 1982, the cemetery is currently being closed as the first step toward relocation of the historic building. The following are comments by Rev F E Leadley published at the time of the centenary in 1956 - "A hundred years ago, one of a number of small settlements bordering the Manukau Harbour was known as Taotaoroa. Here a few Europeans took up land. The Maori settlement oflhumatao was situated on the coast about 1½ miles away. It was not until the year 1867 that several of these small groups were united and the district renamed "Mangere". In those early days there were few roads - just tracks through the fern and flax, ti-tree and manuka. One of these tracks came down what is now Westney Road to the beach, and another crossing it at right angles led to the Maori Pa and Methodist Mission Station at Ihumatao. At this intersection, which also marked one corner of Mr William Westney's farm, an area of two acres was generously set aside by him as a gift for a Methodist Church and Burial Ground. -

Route N10 - City to Otara Via Manukau Rd, Onehunga, Mangere and Papatoetoe

ROUTE N10 - CITY TO OTARA VIA MANUKAU RD, ONEHUNGA, MANGERE AND PAPATOETOE Britomart t S Mission F t an t r t sh e S e S Bay St Marys aw Qua College lb n A y S e t A n Vector Okahu Bay St Heliers Vi e z ct t a o u T r S c Arena a Kelly ia Kohimarama Bay s m A S Q Tarltons W t e ak T v a e c i m ll e a Dr Beach es n ki le i D y S Albert r r t P M Park R Mission Bay i d a Auckland t Dr St Heliers d y D S aki r Tama ki o University y m e e Ta l r l l R a n Parnell l r a d D AUT t S t t S S s Myers n d P Ngap e n a ip Park e r i o Auckland Kohimarama n R u m e y d Domain d Q l hape R S R l ga d an R Kar n to d f a N10 r Auckland Hobson Bay G Hospital Orakei P Rid a d de rk Auckland ll R R R d d Museum l d l Kepa Rd R Glendowie e Orakei y College Grafton rn Selwyn a K a B 16 hyb P College rs Glendowie Eden er ie Pass d l Rd Grafton e R d e Terrace r R H Sho t i S d Baradene e R k h K College a Meadowbank rt hyb r No er P Newmarket O Orakei ew ass R Sacred N d We Heart Mt Eden Basin s t Newmarket T College y a Auckland a m w a ki Rd Grammar d a d Mercy o Meadowbank R r s Hospital B St Johns n Theological h o St John College J s R t R d S em Remuera Va u Glen ll d e ey G ra R R d r R Innes e d d St Johns u a Tamaki R a t 1 i College k S o e e u V u k a v lle n th A a ra y R R d s O ra M d e Rd e u Glen Innes i em l R l i Remuera G Pt England Mt Eden UOA Mt St John L College of a Auckland Education d t University s i e d Ak Normal Int Ea Tamaki s R Kohia School e Epsom M Campus S an n L o e i u n l t e e d h re Ascot Ba E e s Way l St Cuthberts -

The Flowing Tide 1850-1950 a Brief Outline of the Onehunga Methodist Church and Its Influence Through One Hundred Years

The Flowing Tide by Rev. Frank. E. Leadley The Flowing Tide 1850-1950 A brief outline of the Onehunga Methodist Church and its influence through one hundred years. Prepared by Rev. Frank. E. Leadley First Onehunga Methodist Church, 1850 Wesley Historical Society (NZ) Publication #8(1) 1950 Page 1 The Flowing Tide by Rev. Frank. E. Leadley INTRODUCTION Looking back to the early days of the Christian Gospel in New Zealand, it must be borne in mind that the pioneer Missionaries of both the Anglican and Methodist Churches came predominantly to the Maori people. Indeed, it may be said that fully 80 of Christian teaching a hundred years' ago was given to them. The establishment of churches for the pakeha closely followed the settlements which sprang up rapidly along both east and west coasts of the North Island, as emigrants from Great Britain arrived. It is with devout gratitude to Almighty God, and sincere admiration for a noble company of men and women pioneers, that the Trustees of the Onehunga Methodist Church review a century of Christian service, in which tills Church has been the head of a religious movement which extended through Otahuhu, Papakura, Waiuku, to the Bombay settlement, and Pukekohe; all of which places are today centres of Christian service to the community. The first Methodist Church in Onehunga, built in the year 1850, has long since served its purpose, and been sold. But there remains still in occupation the first Parsonage, a sturdy kauri building, erected in 1840 at Mangungu, at the head of the Hokianga harbour, and in 1855 brought by water and re-erected here. -

Constructing the Other News Media Representations of a Predominantly ‘Brown’ Community in New Zealand

CLIMATE CHANGE IN ASIA-PACIFIC Constructing the Other News media representations of a predominantly ‘brown’ community in New Zealand Abstract: Research worldwide finds that indigenous, non-white, immigrant and other marginalised communities are subjected to media coverage that negatively and narrowly stereotypes them in comparison to dominant racial groups. In this article, we explore media representations of a predominantly Pacific and lower socio-economic community in New Zealand. The results contribute to the literature regarding media coverage of minority communities through an analysis of 388 news articles, drawing on Freire’s (1996/1970) theory of antidialogical action to consider how power is used to marginalise the predominantly Pacific community of South Auckland. The results dem- onstrate that South Aucklanders are subjected to stereotypes and negative labelling that reinforce their marginalisation and exclusion from mainstream New Zealand culture. Keywords: ethnicity, marginalisation, news media, New Zealand, Pacific peoples, Pākehā, representation JEAN M ALLEN and TONI BRUCE University of Auckland Introduction N THIS article, we explore media representations of a predominantly Pacific1 and lower socio-economic community in New Zealand, through the lens of IPaulo Freire’s theory of antidialogical action. For Freire (1970/1996), the pow- er imbalance between what he describes as the haves and have-nots is a form of oppressive action that permits domination over, or prejudicial treatment of, one group or individual by another. In Freire’s (1970/1996) conceptualisation of power as primarily oppressive, power imbalances are maintained through antidialogical action, which limits dialogue between the empowered and the marginalised and hinders the ability of marginalised groups to recognise or gain consciousness of their oppression. -

Restaurant Name

Restaurant Name Address Line 1 Address Line 2 City Name Postal Code Location AGAVE RESTAURANT 685 KARIOITAHI ROAD WAIUKU 2123 SOUTH AUCKLAND AMPHORA RESTAURANT BOTANY JUNCTION S/C 123 ORMISTON ROAD FLAT BUSH 2016 SOUTH AUCKLAND BAZZA'S STEAKHOUSE 56-60 KING STREET PUKEKOHE 2120 SOUTH AUCKLAND BRONCOS STEAK HOUSE 712 GREAT SOUTH RD MANUKAU 2104 SOUTH AUCKLAND CHIN WAGS 8 SEAWAY RD CLARKS BEACH 2122 SOUTH AUCKLAND CURRY LEAF RESTAURANT 49 EDINBURGH STREET PUKEKOHE 2120 SOUTH AUCKLAND DAIKOKU RESTAURANT BOTANY TOWN CENTRE 588 CHAPEL ROAD EAST TAMAKI 2016 SOUTH AUCKLAND DENNY'S 19 LAKEWOOD COURT MANUKAU 2104 SOUTH AUCKLAND DOOLAN BROTHERS BOTANY TOWN CENTRE 588 CHAPEL RD EAST TAMAKI 2016 SOUTH AUCKLAND ED STREET 27 EDINBURGH STREET PUKEKOHE 2120 SOUTH AUCKLAND FISHER HOUSE 117 KERWYN AVE EAST TAMAKI 2013 SOUTH AUCKLAND GOODE BROTHERS BOTANY TOWN CENTRE 588 CHAPEL RD EAST TAMAKI 2016 SOUTH AUCKLAND INDIA RESTAURANT 37B GEORGE STREET TUAKAU 2121 SOUTH AUCKLAND INDIAN ACCENT 308 TE IRIRANGI DRIVE FLAT BUSH 2013 SOUTH AUCKLAND LONE STAR CAFE 8 MASSEY AVENUE PUKEKOHE 2120 SOUTH AUCKLAND LONE STAR CAFE 792 GREAT SOUTH ROAD WIRI 2104 SOUTH AUCKLAND MELBA MANUKAU 1 RONWOOD AVE MANUKAU 2104 SOUTH AUCKLAND MUANG THAI PUKE RESTAURANT 70 KING ST PUKEKOHE 2120 SOUTH AUCKLAND MUMBAI EXPRESS WESTFIELD MANUKAU 6 AMERSHAM WAY MANUKAU 2104 SOUTH AUCKLAND MURPHY'S LAW IRISH BAR 200 GREAT SOUTH RD DRURY 2113 SOUTH AUCKLAND NEW RUBY 2 AVERILL STREET PAPAKURA 2110 SOUTH AUCKLAND REPUBLIC BAR & KITCHEN WESTFIELD MANUKAU 6 AMERSHAM WAY MANUKAU 2104 SOUTH AUCKLAND -

To Manukau Centre Via Mangere East and Papatoetoe to Otahuhu

Rd Panmure y nd Bridge to Otahuhu • Downtown to Manukau Centre w Primary Irela r ve Ri via Papatoetoe and Mangere East via Mangere East and Papatoetoe on H aki Panmure Rd m a Basin anga T B rose llingt ur ai Pen R e Pak l ey R ey d St Kentigern Mt Wellington W College d t R d Countdown anga M ur Waipuna Rd Pak Manukau Papatoetoe Customs St Papatoetoe P ri Centre Town Hall Transfer Otahuhu Customs St East Otahuhu Transfer Otahuhu Town Hall Manukau ce Cr Route (Stop 6921) (Stop 6525) Otahuhu at Otahuhu (Stop 8094) East Route (Stop 7019) (Stop 8099) at Otahuhu (Stop 8099) (Stop 6520) Centre Sylvia Park 10 Primary Sylvia Park R Monday to Friday 428 Monday to Friday 428 ee d ves Rd R Riverina Sou Mt th Sylvia Park School 10 Ti ys e Pl d rn den M Wel Shopping Bow R U AM 428 5.30 5.37 5.55 471 6.05 6.41 AM --428 6.40 6.57 7.11 ot akau Dr orw Centre ay l 428 6.00 6.07 6.30 473 6.35 7.19 497 6.25 7.00 428 7.10 7.32 7.46 i r ng D mow C G Hamlins le a C reat Hill t rb 428 6.30 6.37 7.00 473 7.05 7.58 471 6.45 7.25 428 7.40 8.06 8.20 o T ine R a n r Pl bado m S Hig Ga ou Rd 428 7.00 7.10 7.32 471 7.40 8.46 497 7.15 8.00 428 8.10 8.41 8.55 Rd a rk ahan d t Mon k jway i h a Pa Edgewater 428 7.30 7.40 8.07 471 8.15 9.15 487 8.15 9.00 428 9.10 9.35 9.50 vi r Cr R l D 1 College Rd Sy Fisher iv ey e t s r 428 8.00 8.10 8.40 471 8.45 9.45 487 9.15 10.00 428 10.10 10.35 10.50 e V N ia ek 428 8.30 8.40 9.10 497 9.15 10.05 487 10.15 11.00 428 11.10 11.35 11.50 ll B re Transferu s Rd at Otahuhu Pakuranga C 428 9.10 9.20 9.50 487 9.55 10.45 487 11.15 12.00 428 -

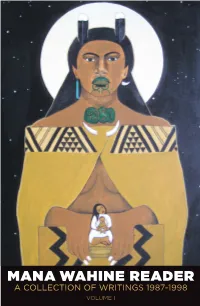

MANA WAHINE READER a COLLECTION of WRITINGS 1987-1998 2 VOLUME I Mana Wahine Reader a Collection of Writings 1987-1998 Volume I

MANA WAHINE READER A COLLECTION OF WRITINGS 1987-1998 2 VOLUME I Mana Wahine Reader A Collection of Writings 1987-1998 Volume I I First Published 2019 by Te Kotahi Research Institute Hamilton, Aotearoa/ New Zealand ISBN: 978-0-9941217-6-9 Education Research Monograph 3 © Te Kotahi Research Institute, 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without prior written permission of the publisher. Design Te Kotahi Research Institute Cover illustration by Robyn Kahukiwa Print Waikato Print – Gravitas Media The Mana Wahine Publication was supported by: Disclaimer: The editors and publisher gratefully acknowledge the permission granted to reproduce the material within this reader. Every attempt has been made to ensure that the information in this book is correct and that articles are as provided in their original publications. To check any details please refer to the original publication. II Mana Wahine Reader | A Collection of Writings 1987-1998, Volume I Mana Wahine Reader A Collection of Writings 1987-1998 Volume I Edited by: Leonie Pihama, Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Naomi Simmonds, Joeliee Seed-Pihama and Kirsten Gabel III Table of contents Poem Don’t Mess with the Māori Woman - Linda Tuhiwai Smith 01 Article 01 To Us the Dreamers are Important - Rangimarie Mihomiho Rose Pere 04 Article 02 He Aha Te Mea Nui? - Waerete Norman 13 Article 03 He Whiriwhiri Wahine: Framing Women’s Studies for Aotearoa Ngahuia Te Awekotuku 19 Article 04 Kia Mau, Kia Manawanui -

We're Changing the Way You Park

We’re changing the way you park A Major construction is now underway at Auckland Airport as we build the Airport of the Future. The next phase of development will have a significant impact on the capacity of the terminal carparks, meaning we will need to make some changes to where staff park. What’s changing? We are moving over 700 staff car parks to the expanded Park&Ride car park on Verissimo Drive. This is to accommodate the start of major construction around the international terminal precinct. In this area we will expand the international arrivals area, construct a new five-star hotel and, most significantly, begin works on the new domestic jet terminal of what will ultimately be a combined domestic and international airport. Who will be moving? All staff located in staff car park 7 will be relocated to the Verissimo Drive car park, where we have developed an additional 1000 spaces and a new bus shelter exclusively for staff. 1 Auckland Airport What is Park&Ride? Park&Ride is a secure parking facility that offers a free transfer service to both terminals, and is located only a few minutes away. The Park&Ride service operates 24 hours a day providing dedicated buses to each terminal. We have increased the frequency of the shuttle service to and from the international terminal to every five minutes from 4am to midnight. We have also developed a contingency route for the bus to use at peak congestion to maintain access to and from the international terminal. How will this affect me? As the Park&Ride buses operate to a schedule, we suggest that you plan an extra 10-15 minutes into your journey to ensure you arrive at or leave work on time. -

Onehunga “Masterplan”- W 10 Concept Sketch

ONEHUNGA “MASTERPLAN”- W 10 CONCEPT SKETCH ONEHUNGA - CONCEPTUAL MASTERPLAN STUDY - UPDATE 20.05.2017 W 10 CAFE’S / OFFICES/ RESIDENTIAL LIGHT RAIL VOLCANIC PARK STATION HOTEL OFFICES CONFERENCE CTR. MARINE INDUSTRIES MALL OFFICES RESIDENTIAL ENTERTAINMENT ONEHUNGA WHARF ONEHUNGA - CONCEPTUAL MASTERPLAN STUDY - UPDATE 20.05.2017 W 10 REFERENCE IMAGE BY UN STUDIO REFERENCE IMAGE BY UN STUDIO REFERENCE IMAGE BY GRAFT ONEHUNGA WHARF - OFFICE TOWER / HOTEL / CONFERENCE CTR. / MALL ONEHUNGA - CONCEPTUAL MASTERPLAN STUDY - UPDATE 20.05.2017 W 10 ONEHUNGA WHARF REFERENCE IMAGES FROM HAMBURG HARBOUR CITY AND WYNYARD QUARTER ONEHUNGA - CONCEPTUAL MASTERPLAN STUDY - UPDATE 20.05.2017 W 10 LIGHT RAIL LIGHT RAIL PEDESTRIANS AND CYCLISTS TO EAST WEST LINK BUSINESS PARK ONEHUNGA - TRAFFIC ORGANISATION ONEHUNGA - CONCEPTUAL MASTERPLAN STUDY - UPDATE 20.05.2017 W 10 HUNTERS POINT SOUTH PARK NEW YORK MINGHU WETLAND PARK, LIUPANSHUI, GUIZHOU, CHINA CHRISTO “FLOATING PIERS” LAKE ISEO, ITALY THE VOLCANIC CONE DESERVES TO BE HIGHLIGHTED IN A SUSTAINABLE AND ARTISTIC WAY ONEHUNGA - CONCEPTUAL MASTERPLAN STUDY - UPDATE 20.05.2017 W 10 MANGERE INTERSECTION ONEHUNGA - CONCEPTUAL MASTERPLAN STUDY - UPDATE 20.05.2017 W 10 Sedimentation, Ecological Reclamation, ECOLOGICAL RESTORATIVE RECLAMATION Brown Field Development. The foreshore of Onehunga, from south of the Taumanu Re- serve, around the wharf, and all along the Mangere Inlet, has The extensive construction activities during the implemen- been subject to decades of industrially polluted runoff; tation of the East West Link, offer the unique oportunity to tackle the issue of existing pollution. As part of its sustainable city development strategy Auck- land prioritises Brownfield developments along traffic corri- By considering Public - Private - Partnerships, the value of the dors for city expansion. -

Auckland's Urban Form

A brief history of Auckland’s urban form April 2010 A brief history of Auckland’s urban form April 2010 Introduction 3 1840 – 1859: The inaugural years 5 1860 – 1879: Land wars and development of rail lines 7 1880 – 1899: Economic expansion 9 1900 – 1929: Turning into a city 11 1930 – 1949: Emergence of State housing provision 13 1950 – 1969: Major decisions 15 1970 – 1979: Continued outward growth 19 1980 – 1989: Intensifi cation through infi ll housing 21 1990 – 1999: Strategies for growth 22 2000 – 2009: The new millennium 25 Conclusion 26 References and further reading 27 Front cover, top image: North Shore, Auckland (circa 1860s) artist unknown, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki, gift of Marshall Seifert, 1991 This report was prepared by the Social and Economic Research and Monitoring team, Auckland Regional Council, April 2010 ISBN 978-1-877540-57-8 2 History of Auckland’s Urban Form Auckland region Built up area 2009 History of Auckland’s Urban Form 3 Introduction This report he main feature of human settlement in the Auckland region has been the development This report outlines the of a substantial urban area (the largest in development of Auckland’s New Zealand) in which approximately 90% urban form, from early colonial Tof the regional population live. This metropolitan area settlement to the modern Auckland is located on and around the central isthmus and metropolis. It attempts to capture occupies around 10% of the regional land mass. Home the context and key relevant to over 1.4 million people, Auckland is a vibrant centre drivers behind the growth in for trade, commerce, culture and employment.