University Teaching About the Holocaust in Germany

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Humiliation to Humanity Reconciling Helen Goldman’S Testimony with the Forensic Strictures of the Frankfurt Auschwitz Trial

S: I. M. O. N. Vol. 8|2021|No.1 SHOAH: INTERVENTION. METHODS. DOCUMENTATION. Andrew Clark Wisely From Humiliation to Humanity Reconciling Helen Goldman’s Testimony with the Forensic Strictures of the Frankfurt Auschwitz Trial Abstract On 3 September 1964, during the Frankfurt Auschwitz trial, Helen Goldman accused SS camp doctor Franz Lucas of selecting her mother and siblings for the gas chamber when the family arrived at Birkenau in May 1944. Although she could identify Lucas, the court con- sidered her information under cross-examination too inconsistent to build a case against Lucas. To appreciate Goldman’s authority, we must remove her from the humiliation of the West German legal gaze and inquire instead how she is seen through the lens of witness hospitality (directly by Emmi Bonhoeffer) and psychiatric assessment (indirectly by Dr Walter von Baeyer). The appearance of Auschwitz survivor Helen (Kaufman) Goldman in the court- room of the Frankfurt Auschwitz trial on 3 September 1964 was hard to forget for all onlookers. Goldman accused the former SS camp doctor Dr Franz Lucas of se- lecting her mother and younger siblings for the gas chamber on the day the family arrived at Birkenau in May 1944.1 Lucas, considered the best behaved of the twenty defendants during the twenty-month-long trial, claimed not to recognise his accus- er, who after identifying him from a line-up became increasingly distraught under cross-examination. Ultimately, the court rejected Goldman’s accusations, choosing instead to believe survivors of Ravensbrück who recounted that Lucas had helped them survive the final months of the war.2 Goldman’s breakdown of credibility echoed the experience of many prosecution witnesses in West German postwar tri- als after 1949. -

Einsicht 16 Bulletin Des Fritz Bauer Instituts

Einsicht 16 Bulletin des Fritz Bauer Instituts , Völkermorde vor Gericht: Fritz Bauer Institut Von Nürnberg nach Den Haag Geschichte und MMitit BBeiträgeneiträgen vonvon KKimim PPriemel,riemel, WWolfgangolfgang Wirkung des Holocaust FForm/Axelorm/Axel FFischerischer uundnd VolkerVolker ZimmermannZimmermann Editorial Liebe Leserinnen und Leser, zur Grundlage der NSG-Verfahren zu machen, erscheint spätestens seit dem Münchner Demjanjuk-Urteil von 2011 in einem neuen, von den Nürnberger Prozessen über den kritischen Licht. Eichmann-Prozess in Jerusalem und die Nicolas Berg, Gastwissenschaftler am Fritz Bauer Institut im Prozesse an bundesdeutschen Landge- Wintersemester 2015/2016, beschäftigt sich in seinem Beitrag mit richten – wie den Chełmno-Prozess in den Spielfi lmen über Fritz Bauer, die während der beiden letzten Bonn, den Auschwitz-Prozess in Frank- Jahre in Kino und Fernsehen ein großes Publikum erreicht haben. furt am Main, den Sobibór-Prozess in Berg beginnt seine Darstellung mit der Skizze einer, wie er selbst Hagen und die Prozesse zu Treblinka sagt, noch nicht geschriebenen Wirkungs- und Rezeptionsgeschichte und Majdanek in Düsseldorf – zum In- Fritz Bauers, um vor deren Hintergrund herauszuarbeiten, wie in den ternationalen Strafgerichtshof in Den drei Filmen »die Persönlichkeit Bauers, sein Lebenswerk und sein Haag war es ein schwieriger und viel- privates Schicksal hier zum Gegenstand einer Selbstansprache der fach unterbrochener Weg. Ist es nicht Gegenwart« geworden sind. eine Überbewertung bundesdeutscher Timothy Snyder, -

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Inhaltsverzeichnis Kirche in unserem Magdeburger Land. Thietmar von Merseburg. E. K 31 Bischof Johannes Braun Dom und Domstiftsbibliothek von Merseburg. E. K 31 Bistum Zeitz. E. K 32 Bischof Julius Pflug - der letzte Bischof von Zeitz-Naum- 1. Kapitel burg. E. K./O. M 32 Vielgestaltige Landschaft Im Jahre 1032. Das Bistum Zeitz wird nach Naumburg ver- legt. Albert Hauck 33 Die Elbe. Elfride Kiel 7 Der Dom zu Naumburg. H. S./E. S./E. K 3; Fruchtbare Magdeburger Börde. Nach Lothar Cumpertl Dunkel und Schatten - Glaubenskämpfe und Reformen. Heinz Glade/Elfride Kiel 8 Weihbischof Friedrich Maria Rintelen 34 192 Ortsnamen mit »leben«. E. K 9 Carl van Eß - ein Benediktiner. Elfride Kiel 34 Wasser aus der Heide. Nach Fritz OelzelHeinz Gladel Neues katholisches Leben 37 Elfride Kiel 9 Magdeburger Katholikentag 1928. Carl Sonnenschein 37 In der Altmark. Elfride Kiel 10 Das Motiv des Katholikentags in Magdeburg 38 Harzvorland und Huy. Elfride Kiel 11 1945 - Zerstörung Magdeburgs und Wiederaufbau 38 Harzland. Elfride Kiel 12 1949 - Magdeburg Sitz eines Weihbischofs. Weihbischof Aus Sumpfland wurde »Goldene Aue«. M. Nick 14 Friedrich Maria Rintelen 38 Der Fläming - »die Fläminge«. Nach Helmar Jungbans/Karl Wie Magdeburg die 1000-Jahr-Feier beging. /• G.IE. K. 38 BischoflElfride Kiel 14 Glauben zwischen gestern und morgen. Elfride Kiel 39 Mansfelder Land. Elfride Kiel 15 Kunst und Geschichte in St. Sebastian in Magdeburg. Bischof Querfurter Platte. Elfride Kiel 16 Johannes Braun 42 Saale und Unstrut. Elfride Kiel 16 Sankt Norbert — Patron des Bischöflichen Amtes Magdeburg. Im Unstruttal. Elfride Kiel 18 Aus der Predigt von Bischof Braun am }./6. -

Zum Gedenken an Peter Borowsky

Hamburg University Press Zum Gedenken an Peter Borowsky Hamburger Universitätsreden Neue Folge 3 Zum Gedenken an Peter Borowsky Hamburger Universitätsreden Neue Folge 3 Herausgeber: Der Präsident der Universität Hamburg ZUM GEDENKEN AN PETER BOROWSKY herausgegeben von Rainer Hering und Rainer Nicolaysen Hamburg University Press © 2003 Peter Borowsky INHALT 9 Zeittafel Peter Borowsky 15 Vorwort 17 TRAUERFEIER FRIEDHOF HAMBURG-NIENSTEDTEN, 20. OKTOBER 2000 19 Gertraud Gutzmann Nachdenken über Peter Borowsky 25 Rainer Nicolaysen Trauerrede für Peter Borowsky 31 GEDENKFEIER UNIVERSITÄT HAMBURG, 8. FEBRUAR 2001 33 Wilfried Hartmann Grußwort des Vizepräsidenten der Universität Hamburg 41 Barbara Vogel Rede auf der akademischen Gedenkfeier für Peter Borowsky 53 Rainer Hering Der Hochschullehrer Peter Borowsky 61 Klemens von Klemperer Anderer Widerstand – anderes Deutschland? Formen des Widerstands im „Dritten Reich“ – ein Überblick 93 GEDENKFEIER SMITH COLLEGE, 27. MÄRZ 2001 95 Joachim Stieber Peter Borowsky, Member of the Department of History in Recurring Visits 103 Hans Rudolf Vaget The Political Ramifications of Hitler’s Cult of Wagner 129 ANHANG 131 Bibliographie Peter Borowsky 139 Gedenkschrift für Peter Borowsky – Inhaltsübersicht 147 Rednerinnen und Redner 149 Impressum ZEITTAFEL Peter Borowsky 1938 Peter Borowsky wird am 3. Juni als Sohn von Margare- te und Kurt Borowsky, einem selbstständigen Einzel- handelskaufmann, in Angerburg/Ostpreußen geboren 1944 im Herbst Einschulung in Angerburg 1945 nach der Flucht aus Ostpreußen von Januar -

Erinnerungen Pfarrer Zuelicke.Pdf

1 GELEITWORT Bei den Erinnerungen an mein Leben möchte ich mich von dem Stichwort „Anfänge“ leiten lassen. Na- türlich ist jeder Tag ein Anfang, der uns herausfordert, ihn zu gestalten. Da steht oft die Frage: Was fangen wir mit diesem Menschen oder mit diesem Tag an? Es gibt sicher auch Tage, mit denen wir, so scheint es, nichts anfangen können. Wie also gehen wir mit den Gegebenheiten um, die auf uns zukom- men? Manchmal entscheiden wir uns ganz bewusst für einen Neuanfang, vor allem dann, wenn wir hinter eine unangenehme Sache einen Schlussstrich ziehen wollen. Es kann auch sein, dass uns etwas wertvoll erscheint und reizt, etwas Neues auszuprobieren oder zu wagen. Oft genug bedeutet ein An- fang eine Weichenstellung, verbunden mit besonderen Herausforderungen und Entscheidungen. Ein Anfang führt aber auch immer zu einem Ende, dem dann ein Neuanfang folgen kann. Davon habe ich in meinem Leben eine ganze Reihe erfahren und möchte davon schreiben. Der Schwerpunkt meiner Ausführungen wird durch die Orte gesetzt, an denen ich gelebt und gewirkt habe. Zunächst schaue ich aber auf die ersten 25 Jahre bis zu meiner Priesterweihe. Wolmirstedt, im Corona-Sommer 2020 Peter Zülicke Bild 1: In der „Studierstube“ 2020 2 DIE ERSTEN BEIDEN JAHRZEHNTE chon meine Geburt am 13. Februar 1938 im Magdeburger Marienstift war ein prägender Anfang, den ich natürlich noch nicht bewusst wahrgenommen habe. Dieses kleine Wesen, das den bergen- S den Mutterschoß verlassen hatte, musste sich nun als Individuum total in einer anderen Umge- bung zurechtfinden. Ich ahne nur, wie gut mir die bergende und sorgende Liebe meiner Eltern getan hat. -

Social Penetration and Police Action: Collaboration Structures in the Repertory of Gestapo Activities

Social Penetration and Police Action: Collaboration Structures in the Repertory of Gestapo Activities KLAUS-MICHAEL MALLMANN* SUMMARY: The twentieth century was "short", running only from 1914 to 1990/ 1991. Even so, it will doubtless enter history as an unprecedented era of dictatorships. The question of how these totalitarian regimes functioned in practice, how and to what extent they were able to realize their power aspirations, has until now been answered empirically at most highly selectively. Extensive comparative research efforts will be required over the coming decades. The police as the key organization in the state monopoly of power is particularly important in this context, since like no other institution it operates at the interface of state and society. Using the example of the Gestapo's activities in the Third Reich, this article analyses collaboration structures between these two spheres, which made possible (either on a voluntary or coercive basis) a penetration of social contexts and hence police action even in shielded areas. It is my thesis that such exchange processes through unsolicited denunciation and informers with double identities will also have been decisive outside Germany in the tracking of dissident behaviour and the detection of conspiratorial practices. I do not think it is too far-fetched to say that the century which is about to end will go down in history as the era of dictatorships. But a social history of this state-legitimized and -executed terror, let alone an interna- tional comparison on a solid -

German History Reflected

The Detlev Rohwedder Building German history reflected GFE = 1/2 Formathöhe The Detlev Rohwedder Building German history reflected Contents 3 Introduction 44 Reunification and Change 46 The euphoria of unity 4 The Reich Aviation Ministry 48 A tainted place 50 The Treuhandanstalt 6 Inception 53 The architecture of reunification 10 The nerve centre of power 56 In conversation with 14 Courage to resist: the Rote Kapelle Hans-Michael Meyer-Sebastian 18 Architecture under the Nazis 58 The Federal Ministry of Finance 22 The House of Ministries 60 A living place today 24 The changing face of a colossus 64 Experiencing and creating history 28 The government clashes with the people 66 How do you feel about working in this building? 32 Socialist aspirations meet social reality 69 A stroll along Wilhelmstrasse 34 Isolation and separation 36 Escape from the state 38 New paths and a dead-end 72 Chronicle of the Detlev Rohwedder Building 40 Architecture after the war – 77 Further reading a building is transformed 79 Imprint 42 In conversation with Jürgen Dröse 2 Contents Introduction The Detlev Rohwedder Building, home to Germany’s the House of Ministries, foreshadowing the country- Federal Ministry of Finance since 1999, bears wide uprising on 17 June. Eight years later, the Berlin witness to the upheavals of recent German history Wall began to cast its shadow just a few steps away. like almost no other structure. After reunification, the Treuhandanstalt, the body Constructed as the Reich Aviation Ministry, the charged with the GDR’s financial liquidation, moved vast site was the nerve centre of power under into the building. -

The Jewish Contribution to the European Integration Project

The Jewish Contribution to the European Integration Project Centre for the Study of European Politics and Society Ben-Gurion University of the Negev May 7 2013 CONTENTS Welcoming Remarks………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………1 Dr. Sharon Pardo, Director Centre for the Study of European Politics and Society, Jean Monnet National Centre of Excellence at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev Walther Rathenau, Foreign Minister of Germany during the Weimar Republic and the Promotion of European Integration…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………3 Dr. Hubertus von Morr, Ambassador (ret), Lecturer in International Law and Political Science, Bonn University Fritz Bauer's Contribution to the Re-establishment of the Rule of Law, a Democratic State, and the Promotion of European Integration …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………8 Mr. Franco Burgio, Programme Coordinator European Commission, Brussels Rising from the Ashes: the Shoah and the European Integration Project…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………13 Mr. Michael Mertes, Director Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, Israel Contributions of 'Sefarad' to Europe………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………21 Ambassador Alvaro Albacete, Envoy of the Spanish Government for Relations with the Jewish Community and Jewish Organisations The Cultural Dimension of Jewish European Identity………………………………………………………………………………….…26 Dr. Dov Maimon, Jewish People Policy Institute, Israel Anti-Semitism from a European Union Institutional Perspective………………………………………………………………34 -

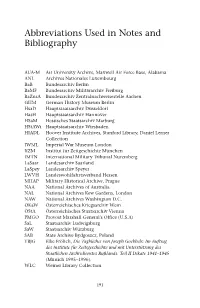

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography AUA-M Air University Archive, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama ANL Archives Nationales Luxembourg BaB Bundesarchiv Berlin BaMF Bundesarchiv Militärarchiv Freiburg BaZnsA Bundesarchiv Zentralnachweisestelle Aachen GHM German History Museum Berlin HsaD Hauptstaatsarchiv Düsseldorf HasH Hauptstaatsarchiv Hannover HSaM Hessisches Staatsarchiv Marburg HStAWi Hauptstaatsarchiv Wiesbaden HIADL Hoover Institute Archives, Stanford Library, Daniel Lerner Collection IWML Imperial War Museum London IfZM Institut für Zeitgeschichte München IMTN International Military Tribunal Nuremberg LaSaar Landesarchiv Saarland LaSpey Landesarchiv Speyer LWVH Landeswohlfahrtsverband Hessen MHAP Military Historical Archive, Prague NAA National Archives of Australia NAL National Archives Kew Gardens, London NAW National Archives Washington D.C. OKaW Österreichisches Kriegsarchiv Wein ÖStA Österreichisches Staatsarchiv Vienna PMGO Provost Marshall General’s Office (U.S.A) SaL Staatsarchiv Ludwigsburg SaW Staatsarchiv Würzburg SAB State Archive Bydgoszcz, Poland TBJG Elke Frölich, Die Tagbücher von Joseph Goebbels: Im Auftrag des Institute für Zeitsgeschichte und mit Unterstützung des Staatlichen Archivdienstes Rußlands. Teil II Dikate 1941–1945 (Münich 1995–1996). WLC Weiner Library Collection 191 Notes Introduction: Sippenhaft, Terror and Fear: The Historiography of the Nazi Terror State 1 . Christopher Hutton, Race and the Third Reich: Linguistics, Racial Anthropology and Genetics in the Third Reich (Cambridge 2005), p. 18. 2 . Rosemary O’Kane, Terror, Force and States: The Path from Modernity (Cheltham 1996), p. 19. O’Kane defines a system of terror, as one that is ‘distinguished by summary justice, where the innocence or guilt of the victims is immaterial’. 3 . See Robert Thurston, ‘The Family during the Great Terror 1935–1941’, Soviet Studies , 43, 3 (1991), pp. 553–74. -

Roma and Sinti Under-Studied Victims of Nazism

UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM CENTER FOR ADVANCED HOLOCAUST STUDIES Roma and Sinti Under-Studied Victims of Nazism Symposium Proceedings W A S H I N G T O N , D. C. Roma and Sinti Under-Studied Victims of Nazism Symposium Proceedings CENTER FOR ADVANCED HOLOCAUST STUDIES UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM 2002 The assertions, opinions, and conclusions in this occasional paper are those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Holocaust Memorial Council or of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Third printing, July 2004 Copyright © 2002 by Ian Hancock, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2002 by Michael Zimmermann, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2002 by Guenter Lewy, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2002 by Mark Biondich, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2002 by Denis Peschanski, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2002 by Viorel Achim, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2002 by David M. Crowe, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Contents Foreword .....................................................................................................................................i Paul A. Shapiro and Robert M. Ehrenreich Romani Americans (“Gypsies”).......................................................................................................1 Ian -

Introduction Norman J.W

Introduction Norman J.W. Goda E The examination of legal proceedings related to Nazi Germany’s war and the Holocaust has expanded signifi cantly in the past two decades. It was not always so. Though the Trial of the Major War Criminals at Nuremberg in 1945–1946 generated signifi cant scholarly literature, most of it, at least in the trial’s immediate aftermath, concerned legal scholars’ judgments of the trial’s effi cacy from a strictly legalistic perspective. Was the four-power trial based on ex post facto law and thus problematic for that reason, or did it provide the best possible due process to the defendants under the circumstances?1 Cold War political wrangl ing over the subsequent Allied trials in the western German occupation zones as well as the sentences that they pronounced generated a discourse that was far more critical of the tri- als than laudatory.2 Historians, meanwhile, used the records assembled at Nuremberg as an entrée into other captured German records as they wrote initial studies of the Third Reich, these focusing mainly on foreign policy and wartime strategy, though also to some degree on the Final Solution to the Jewish Question.3 But they did not historicize the trial, nor any of subsequent trials, as such. Studies that analyzed the postwar proceedings in and of themselves from a historical perspective developed only three de- cades after Nuremberg, and they focused mainly on the origins of the initial, groundbreaking trial.4 Matters changed in the 1990s for a number of reasons. The fi rst was late- and post-Cold War interest among historians of Germany, and of other nations too, in Vergangenheitsbewältigung—the political, social, and intellectual attempt to confront, or to sidestep, the criminal wartime past. -

German Economic Policy and Forced Labor of Jews in the General Government, 1939–1943 Witold Wojciech Me¸Dykowski

Macht Arbeit Frei? German Economic Policy and Forced Labor of Jews in the General Government, 1939–1943 Witold Wojciech Me¸dykowski Boston 2018 Jews of Poland Series Editor ANTONY POLONSKY (Brandeis University) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: the bibliographic record for this title is available from the Library of Congress. © Academic Studies Press, 2018 ISBN 978-1-61811-596-6 (hardcover) ISBN 978-1-61811-597-3 (electronic) Book design by Kryon Publishing Services (P) Ltd. www.kryonpublishing.com Academic Studies Press 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA P: (617)782-6290 F: (857)241-3149 [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com This publication is supported by An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access for the public good. The Open Access ISBN for this book is 978-1-61811-907-0. More information about the initiative and links to the Open Access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. To Luba, with special thanks and gratitude Table of Contents Acknowledgements v Introduction vii Part One Chapter 1: The War against Poland and the Beginning of German Economic Policy in the Ocсupied Territory 1 Chapter 2: Forced Labor from the Period of Military Government until the Beginning of Ghettoization 18 Chapter 3: Forced Labor in the Ghettos and Labor Detachments 74 Chapter 4: Forced Labor in the Labor Camps 134 Part Two Chapter