New York, New York: America's Hero

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New York City, NY

REACHING FOR ZERO: The Citizens Plan for Zero Waste in New York City A “Working Document” 1st Version By Resa Dimino and Barbara Warren New York City Zero Waste Campaign and Consumer Policy Institute / Consumers Union June 2004 Consumer Policy Institute New York City Zero Waste Campaign Consumers Union c/o NY Lawyers for the Public Interest 101 Truman Ave. 151 West 30th Street, 11th Floor Yonkers, NY 10703-1057 New York, New York 10001 914-378-2455 212-244-4664 The New York City Zero Waste Campaign was first conceived at the 2nd National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit in October of 2002, where City activists were confronted with the ongoing concerns of other Environmental Justice communities that would continue to be burdened with the high volume of waste being exported from NYC. As a result of discussion with various activists in the City and elsewhere, a diverse group of environmental, social justice and neighborhood organizations came together to begin the process of planning for Zero Waste in NYC. A series of principles were initially drafted to serve as a basis for the entire plan. It is the Campaign’s intent to expand discussions about the Zero Waste goal and to gain broad support for the detailed plan. The Consumer Policy Institute is a division of Consumers Union, publisher of Consumer Reports magazine. The Institute was established to do research and education on environmental quality, public health and economic justice and other issues of concern to consumers. The Consumer Policy Institute is funded by foundation grants, government contracts, individual donations, and by Consumers Union. -

City of New York 2012-2013 Districting Commission

SUBMISSION UNDER SECTION 5 OF THE VOTING RIGHTS ACT (42 U.S.C. § 1973c) CITY OF NEW YORK 2012-2013 DISTRICTING COMMISSION Submission for Preclearance of the Final Districting Plan for the Council of the City of New York Plan Adopted by the Commission: February 6, 2013 Plan Filed with the City Clerk: March 4, 2013 Dated: March 22, 2013 EXPEDITED PRECLEARANCE REQUESTED TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 1 II. EXPEDITED CONSIDERATION (28 C.F.R. § 51.34) ................................................. 3 III. THE NEW YORK CITY COUNCIL.............................................................................. 4 IV. THE NEW YORK CITY DISTRICTING COMMISSION ......................................... 4 A. Districting Commission Members ....................................................................... 4 B. Commissioner Training ........................................................................................ 5 C. Public Meetings ..................................................................................................... 6 V. DISTRICTING PROCESS PER CITY CHARTER ..................................................... 7 A. Schedule ................................................................................................................. 7 B. Criteria .................................................................................................................. -

Bad Cops: a Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Bad Cops: A Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers Author(s): James J. Fyfe ; Robert Kane Document No.: 215795 Date Received: September 2006 Award Number: 96-IJ-CX-0053 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Bad Cops: A Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers James J. Fyfe John Jay College of Criminal Justice and New York City Police Department Robert Kane American University Final Version Submitted to the United States Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice February 2005 This project was supported by Grant No. 1996-IJ-CX-0053 awarded by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. Points of views in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. -

The New York Times NEW YORK CITY POLL

For paper of Oct. 28 The New York Times NEW YORK CITY POLL Oct. 21-26, 2005 Total N = 993 Registered N = 758 Likely voters N = 616 Results are based on the total citywide sample unless otherwise noted. An asterisk indicates registered respondents. TRENDS ARE BASED NEW YORK TIMES POLLS, EXCEPT: NEW YORK TIMES/CBS NEWS POLLS: OCT. 1998 - OCT. 2000, OCT. 6-9, 2001, JUNE AND AUG. 2002, AND JULY 2003; NEW YORK TIMES/WCBS NEWS POLLS: APRIL 1985 - JUNE 1990, MAY 1993 - OCT. 1994. 1. What's your long range view for the city -- do you think that ten or fifteen years from now, New York City will be a better place to live than it is now, a worse place, or about the same? Better Worse Same Better & worse DK/NA 11/731 38 32 26 4 8/77 27 42 18 13 12/77 38 34 17 11 12/7-14/81 30 40 22 7 1/5-10/85 30 31 27 5 6 1/4-6/87 26 35 31 4 5 1/10-12/88 24 42 28 6 6/11-17/89 22 48 24 1 5 6/17-10/90 20 51 24 4 11/2-12/91 19 58 17 5 5/10-14/93 22 50 23 - 5 3/1-6/97 28 36 29 1 6 8/5-12/01 34 25 32 1 9 10/6-9/01 54 11 26 1 8 10/27-11/1/01 51 12 26 2 9 6/4-9/02 41 20 31 1 6 8/25-29/02 33 23 38 1 6 1/11-15/03 34 26 32 2 7 6/6-11/03 30 33 29 1 7 8/31-9/4/03 34 31 26 1 8 4/16-21/04 33 28 32 2 6 8/20-25/04 30 32 30 1 6 2/4-13/05 28 29 36 3 4 6/21-26/05 31 29 33 2 5 8/22-28/05 30 26 37 1 5 10/21-26/05 36 24 34 1 5 1 Some people are registered to vote and others are not. -

New York City Comprehensive Waterfront Plan

NEW YORK CITY CoMPREHENSWE WATERFRONT PLAN Reclaiming the City's Edge For Public Discussion Summer 1992 DAVID N. DINKINS, Mayor City of New lVrk RICHARD L. SCHAFFER, Director Department of City Planning NYC DCP 92-27 NEW YORK CITY COMPREHENSIVE WATERFRONT PLAN CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMA RY 1 INTRODUCTION: SETTING THE COURSE 1 2 PLANNING FRA MEWORK 5 HISTORICAL CONTEXT 5 LEGAL CONTEXT 7 REGULATORY CONTEXT 10 3 THE NATURAL WATERFRONT 17 WATERFRONT RESOURCES AND THEIR SIGNIFICANCE 17 Wetlands 18 Significant Coastal Habitats 21 Beaches and Coastal Erosion Areas 22 Water Quality 26 THE PLAN FOR THE NATURAL WATERFRONT 33 Citywide Strategy 33 Special Natural Waterfront Areas 35 4 THE PUBLIC WATERFRONT 51 THE EXISTING PUBLIC WATERFRONT 52 THE ACCESSIBLE WATERFRONT: ISSUES AND OPPORTUNITIES 63 THE PLAN FOR THE PUBLIC WATERFRONT 70 Regulatory Strategy 70 Public Access Opportunities 71 5 THE WORKING WATERFRONT 83 HISTORY 83 THE WORKING WATERFRONT TODAY 85 WORKING WATERFRONT ISSUES 101 THE PLAN FOR THE WORKING WATERFRONT 106 Designation Significant Maritime and Industrial Areas 107 JFK and LaGuardia Airport Areas 114 Citywide Strategy fo r the Wo rking Waterfront 115 6 THE REDEVELOPING WATER FRONT 119 THE REDEVELOPING WATERFRONT TODAY 119 THE IMPORTANCE OF REDEVELOPMENT 122 WATERFRONT DEVELOPMENT ISSUES 125 REDEVELOPMENT CRITERIA 127 THE PLAN FOR THE REDEVELOPING WATERFRONT 128 7 WATER FRONT ZONING PROPOSAL 145 WATERFRONT AREA 146 ZONING LOTS 147 CALCULATING FLOOR AREA ON WATERFRONTAGE loTS 148 DEFINITION OF WATER DEPENDENT & WATERFRONT ENHANCING USES -

David Norman Dinkins Served As NYS Assemblyman, President of The

David Norman Dinkins served as NYS Assemblyman, President of the NYC Board of Elections, City Clerk, and Manhattan Borough President, before being elected 106th Mayor of the City of New York in 1989. As the first (and only) African American Mayor of NYC, major successes of note under his administration include: “Safe Streets, Safe City: Cops and Kids”; the revitalization of Times Square as we have come to know it; an unprecedented agreement keeping the US Open Tennis Championships in New York City for 99 years – a contract that continues to bring more financial influx to New York City than the Yankees, Mets, Knicks and Rangers COMBINED – comparable to having the Super Bowl in New York for two weeks every year! The Dinkins administration also created Fashion Week, Restaurant Week, and Broadway on Broadway, which have all continued to thrive for decades, attracting international attention and tremendous revenue to the city each year. Mayor Dinkins joined Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA) as a Professor in the Practice of Urban Public Policy in 1994. He has hosted the David N. Dinkins Leadership and Public Policy Forum for 20 years, which welcomed Congressman John Lewis as Keynote Speaker in 2017. 2015 was a notable year for Mayor Dinkins: the landmarked, Centre Street hub of New York City Government was renamed as the David N. Dinkins Municipal Building; the David N. Dinkins Professorship Chair in the Practice of Urban and Public Affairs at SIPA (which was established in 2003) announced its inaugural professor, Michael A Nutter, 98th Mayor of Philadelphia; and the Columbia University Libraries and Rare Books opened the David N. -

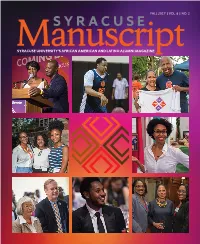

Syracuse Manuscript Are Those of the Authors and Do Not Necessarily Represent the Opinions of Its Editors Or the Policies of Syracuse University

FALL 2017 | VOL. 6 | NO. 2 SYRACUSE ManuscriptSYRACUSE UNIVERSITY’S AFRICAN AMERICAN AND LATINO ALUMNI MAGAZINE CONTENTS ON THE COVER: Left to right, from top: Cheryl Wills ’89 and Taye Diggs ’93; Lazarus Sims ’96; Lt. Col. Pia W. Rogers ’98, G’01, L’01 and Dr. Akima H. Rogers ’94; Amber Hunter ’19, Nerys Castillo-Santana ’19, and Nordia Mullings ’19; Demaris Mercado ’92; Dr. Ruth Chen and Chancellor Kent Syverud; Carmelo Anthony; Darlene Harris ’84 and Debbie Harris ’84 with Soledad O’Brien CONTENTS Contents From the ’Cuse ..........................................................................2 Celebrate Inspire Empower! CBT 2017 ........................3 Chancellor’s Citation Recipients .......................................8 3 Celebrity Basketball Classic............................................ 12 BCCE Marks 40 Years ....................................................... 13 OTHC Milestones ............................................................... 14 13 OTHC Donor List ............................................................17 SU Responds to Natural Disasters ..............................21 Latino/Hispanic Heritage Month ................................22 Anthony Reflects on SU Experience .........................23 Brian Konkol Installed as Dean of Hendricks Chapel ............................................................23 21 26 Diversity and Inclusion Update ...................................24 8 Knight Makes SU History .............................................25 La Casita Celebrates Caribbean Music .....................26 -

The Politics of Charter School Growth and Sustainability in Harlem

REGIMES, REFORM, AND RACE: THE POLITICS OF CHARTER SCHOOL GROWTH AND SUSTAINABILITY IN HARLEM by Basil A. Smikle Jr. Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2019 © 2019 Basil A. Smikle Jr. All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT REGIMES, REFORM, AND RACE: THE POLITICS OF CHARTER SCHOOL GROWTH AND SUSTAINABILITY IN HARLEM By Basil A. Smikle Jr. The complex and thorny relationship betWeen school-district leaders, sub-city political and community figures and teachers’ unions on the subject of charter schools- an interaction fraught with racially charged language and tactics steeped in civil rights-era mobilization - elicits skepticism about the motives of education reformers and their vieW of minority populations. In this study I unpack the local politics around tacit and overt racial appeals in support of NeW York City charter schools with particular attention to Harlem, NeW York and periods when the sustainability of these schools, and long-term education reforms, were endangered by changes in the political and legislative landscape. This dissertation ansWers tWo key questions: How did the Bloomberg-era governing coalition and charter advocates in NeW York City use their political influence and resources to expand and sustain charter schools as a sector; and how does a community with strong historic and cultural narratives around race, education and political activism, respond to attempts to enshrine externally organized school reforms? To ansWer these questions, I employ a case study analysis and rely on Regime Theory to tell the story of the Mayoral administration of Michael Bloomberg and the cadre of charter leaders, philanthropies and wealthy donors whose collective activity created a climate for growth of the sector. -

Vote Ferrer for Mayor November 8Th

Vote Ferrer For Mayor November 8th The Organization of Staff Analysts’ leadership endorsed Fernando Ferrer for Mayor months ago. I have known Freddy since before he held any office at all. As he progressed from legislative assistant to District Leader to City Council member and Borough President, Fred was consistently a friend of the working men and women of the City of New York. He was accessible, informed, considerate and effective. Freddy was especially of value to the Civil Service. His opponent gives him no credit for the turning around of the Bronx. Those of us who came from the Bronx in the 70's and 80's remember the arson that was wiping out housing wholesale. “The Bronx is burning” was proclaimed by national commentators and neither Freddy’s predecessor nor the Mayor had an answer. The answer, put forward and supported by Bronx Borough President Fernando Ferrer, was to increase the number of Fire Marshals, a civil service specialty of firefighters trained to detect and investigate arson. The arsonists were caught and convicted. The burning of the Bronx to cash in on fire insurance ended. Our current Mayor builds stadiums. Freddy saved affordable housing. [continues, over] Fred Ferrer managed budgets both as a Council leader and as a Borough President. His opponent also has managed a budget. When there was a cash shortfall in a bad year, Freddy worked out job sharing and voluntary furloughs. When our current Mayor claimed hardship, he laid off thirty analysts and three thousand other employees. There was no need for those layoffs. -

Culture P5 Bites P14 Blues P3 SMALL BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM the MTA SMALL BUSINESS MENTORING PROGRAM | the MTA SMALL BUSINESS FEDERAL PROGRAM

OCTOBER 03 - OCTOBER 09, 2018 • VOL. 19 • No. 40 WASHINGTON HEIGHTS • INWOOD • HARLEM • EAST HARLEM NORTHERN MANHATTAN’S BILINGUAL NEWSPAPER EL PERIODICO BILINGUE DEL NORTE DE MANHATTAN NOW EVERY WEDNESDAY TODOS LOS MIERCOLES Culture p5 Bites p14 Blues p3 SMALL BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM THE MTA SMALL BUSINESS MENTORING PROGRAM | THE MTA SMALL BUSINESS FEDERAL PROGRAM CALLING ALL SERVICE-DISABLED VETERAN-OWNED BUSINESSES (SDVOBs) ARE YOU READY TO GROW YOUR BUSINESS? Joe Lhota Chairman PRIME CONSTRUCTION CONTRACTS UP TO $3 MILLION I SMALL BUSINESS LOANS UP TO $900,000 Honorable Fernando Ferrer Vice Chairman Patrick Foye President If you’re a certified Service-Disabled Veteran-Owned Businesses (SDVOBs) construction contractor who wants to bid on New York’s lucrative transportation construction contracts, join the elite team at the MTA. Enroll in the award-winning MTA Small Business Development Program, which includes the MTA Small Business Mentoring Program and the MTA Small Business Federal Program. Contracts - Prime Construction Bidding Opportunities up to $3 Million Access to Capital - Small Business Loans up to $900,000 Per Contract Bonding - Access to Surety Bonding Assistance Veronique Hakim Training - Free Classroom Construction Training Managing Director Technical Assistance - MTA Expert Technical Assistance Mentoring - One-on-One Professional Development Free Business Plan Development Back Office Support WHO CAN APPLY NEXT STEPS SDVOBs Visit web.mta.info/sbdp to select the Michael J. Garner, MBA Chief Diversity Officer NYS MWBEs program in which you are interested in and DBEs download the application. You can also call Small Businesses 212.878.7161 for more information. DIVERSITY COMMITTEE MEMBERS Honorable David Jones Honorable Susan G. -

A History of the New York City Corporation Counsel

Touro Law Review Volume 25 Number 4 Annual New York State Constitutional Article 17 Issue February 2013 William E. Nelson, Fighting for the City: A History of the New York City Corporation Counsel Douglas D. Scherer Touro Law Center, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/lawreview Part of the Legal History Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Recommended Citation Scherer, Douglas D. (2013) "William E. Nelson, Fighting for the City: A History of the New York City Corporation Counsel," Touro Law Review: Vol. 25 : No. 4 , Article 17. Available at: https://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/lawreview/vol25/iss4/17 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Touro Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. William E. Nelson, Fighting for the City: A History of the New York City Corporation Counsel Cover Page Footnote 25-4 This book review is available in Touro Law Review: https://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/lawreview/vol25/iss4/17 Scherer: FIGHTING FOR THE CITY WILLIAM E. NELSON, FIGHTING FOR THE CITY: A HISTORY OF THE NEW YORK CITY CORPORATION COUNSEL Reviewed by Douglas D. Scherer* Professor Nelson's excellent historical book on the New York City Corporation Counsel focuses on the work of public officials who served as legal advisors and advocated for the City of New York from the founding of the City in 1686 through the end of the admini- stration of Mayor David Dinkins on December 31, 1993. -

The Cost of Their Intentions 2005: an Analysis of the Democratic Mayoral Candidates’ Spending and Tax Proposals

Civic Report No. 45 September 2005 The Cost of Their Intentions 2005: An Analysis of the Democratic Mayoral Candidates’ Spending and Tax Proposals Nicole Gelinas Senior Fellow, The Manhattan Institute for Policy Research C C i CENTER FOR CIVIC INNOVATION A T THE MANHATTAN INSTITUTE Executive Summary Since the mayoral race of 2001, New Yorkers have endured two years of acute fiscal crisis followed by a return to the city’s chronic fiscal troubles. Higher taxes have failed to end these difficulties: While the current budget is balanced, this year’s surplus will be swallowed up by a budget deficit next year. In- formed voters know that the city remains in a perilous fiscal state, with annual deficits of $4 billion to $5 billion forecast as far as the eye can see, even as the economy continues to recover from 9/11 and the bursting of the tech bubble in 2000. Despite these facts, the four Democratic mayoral candidates propose new programs that would hike the city’s projected $53.9 billion budget for next year by, on average, $1.66 billion each. All four candidates also propose to pay for this spending with even higher taxes on high-income earners, commuters or businesses. Former Bronx Borough President Fernando Ferrer would impose taxes on Wall Street trades to pay for school-spending increases, and on owners of vacant property to pay for subsidized housing. Congressman Anthony Weiner would hike taxes on households making more than $1 million a year to fund a middle- class tax cut. City Council Speaker Gifford Miller would hike taxes on all three groups: high-income earn- ers, insurance companies, and commuters.