The Niger-Libya Border: Securing It Without Stabilising It?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

32 Mohamadou Tchinta

1 LASDEL Laboratoire d’études et recherches sur les dynamiques sociales et le développement local _________ BP 12901, Niamey, Niger – tél. (227) 72 37 80 BP 1383, Parakou, Bénin – tél. (229) 61 16 58 Observatoire de la décentralisation au Niger (enquête de référence 2004) Les pouvoirs locaux dans la commune de Tchintabaraden Abdoulaye Mohamadou Enquêteurs : Afélane Alfarouk et Ahmoudou Rhissa février 05 Etudes et Travaux n° 32 Financement FICOD (KfW) 2 Sommaire Introduction 3 Les Kel Dinnig : de la confédération aux communes 3 Objectifs de l’étude et méthodologie 4 1. Le pouvoir local et ses acteurs 6 1.1. Histoire administrative de l’arrondissement et naissance d’un centre urbain 6 1.2. Les acteurs de l’arène politique locale 7 2. Le découpage de l’arrondissement de Tchintabaraden 19 2.1. Logiques territoriale et logiques sociales 19 2.2. Le choix des bureaux de vote 22 2.3. Les stratégies des partis politiques pour le choix des conseillers 23 2.4. La décentralisation vue par les acteurs 23 3. L’organisation actuelle des finances locales 25 3.1. Les projets de développement 25 3. 2. Le budget de l’arrondissement 26 Conclusion 33 3 Introduction Les Kel Dinnig : de la confédération aux communes L’arrondisssement de Tchintabaraden correspondait avant la création de celui d’Abalak en 1992 à l’espace géographique et social des Touareg Iwillimenden ou Kel Dinnig. Après la révolte de Kaocen en 1916-1917 et son anéantissement par les troupes coloniales françaises, l’aménokalat des Iwilimenden fut disloqué et réparti en plusieurs groupements. Cette technique de diviser pour mieux régner, largement utilisée par l’administration coloniale, constitue le point de départ du découpage administratif pour les populations de cette région. -

Technical Appendix

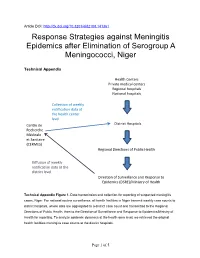

Article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2108.141361 Response Strategies against Meningitis Epidemics after Elimination of Serogroup A Meningococci, Niger Technical Appendix Health Centers Private medical centers Regional hospitals National hospitals Collection of weekly notification data at the health center level Centre de District Hospitals Recherche Médicale et Sanitaire (CERMES) Regional Directions of Public Health Diffusion of weekly notification data at the district level Direction of Surveillance and Response to Epidemics (DSRE)/Ministry of Health Technical Appendix Figure 1. Data transmission and collection for reporting of suspected meningitis cases, Niger. For national routine surveillance, all health facilities in Niger transmit weekly case counts to district hospitals, where data are aggregated to a district case count and transmitted to the Regional Directions of Public Health, then to the Direction of Surveillance and Response to Epidemics/Ministry of Health for reporting. To analyze epidemic dynamics at the health area level, we retrieved the original health facilities meningitis case counts at the district hospitals. Page 1 of 5 Evaluation of Completeness of the Health Center Database The country has 8 regions (Tahoua, Tillabery, Agadez, Diffa, Maradi, Niamey, Zinder, and Dosso), 42 districts, and 732 health areas containing >1,500 health centers. To assess the completeness of this database, we compared the resulting district-level weekly case counts with those included in the national routine surveillance reports. A -

Evaluation Report Agadez Emergency Health Project Care International Pn- 40

FINAL EVALUATION REPORT AGADEZ EMERGENCY HEALTH PROJECT CARE INTERNATIONAL PN- 40 James C. Setzer, MPH Shannon M. Mason, MPH Seydou Abdou Issoufou Mato August 1999 Acknowledgments: The evaluation team would like to take this opportunity to congratulate the Project PN-40 for what is clearly a job well done! They have worked tirelessly to provide important health services to communities that, due to many factors, previously had none. They have done so by using their hands and feet, heads and most importantly their hearts. The results described here would not have been possible if the entire team had not been truly dedicated to improving the health and well-being of the population in their target areas. They have clearly believed in what they set out to do and its importance. In conditions such as these, technical know-how alone is not sufficient to get the job done. For their efforts and dedication then they should be congratulated and thanked. Thanked on behalf of CARE for representing their organization and its mission so well and on behalf of the women and children of northern Niger who will not suffer from preventable illness and death. The evaluation team sincerely hopes that their efforts may in some small way be seen as a contribution to this effort. It is important, also, to thank a number of persons for their input and assistance to this final evaluation exercise. The CARE/Niger country team under the leadership of both Jan Schollert and Douglas Steinberg should be acknowledged for their assistance in putting the evaluation team together and facilitating their work. -

Dynamique Des Conflits Et Médias Au Niger Et À Tahoua Revue De La Littérature

Dynamique des Conflits et Médias au Niger et à Tahoua Revue de la littérature Décembre 2013 Charline Burton Rebecca Justus Contacts: Charline Burton Moutari Aboubacar Spécialiste Conception, Suivi et Coordonnateur National des Evaluation – Afrique de l’Ouest Programmes - Niger Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire [email protected] + 227 9649 00 39 [email protected] +225 44 47 24 57 +227 90 60 54 96 Dynamique des conflits et Médias au Niger et à Tahoua | PAGE 2 Table des matières 1. Résumé exécutif ...................................................................................................... 4 Contexte ................................................................................................. 4 Objectifs et méthodologie ........................................................................ 4 Résultats principaux ............................................................................... 4 2. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 7 2.1 Contexte de la revue de littérature ............................................................... 7 2.2 Méthodologie et questions de recherche ....................................................... 7 3. Contexte général du Niger .................................................................................. 10 3.1 Démographie ............................................................................................. 10 3.2 Situation géographique et géostratégique ............................................ -

Pastoralism and Security in West Africa and the Sahel

Pastoralism and Security in West Africa and the Sahel Towards Peaceful Coexistence UNOWAS STUDY 1 2 Pastoralism and Security in West Africa and the Sahel Towards Peaceful Coexistence UNOWAS STUDY August 2018 3 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations p.8 Chapter 3: THE REPUBLIC OF MALI p.39-48 Acknowledgements p.9 Introduction Foreword p.10 a. Pastoralism and transhumance UNOWAS Mandate p.11 Pastoral Transhumance Methodology and Unit of Analysis of the b. Challenges facing pastoralists Study p.11 A weak state with institutional constraints Executive Summary p.12 Reduced access to pasture and water Introductionp.19 c. Security challenges and the causes and Pastoralism and Transhumance p.21 drivers of conflict Rebellion, terrorism, and the Malian state Chapter 1: BURKINA FASO p.23-30 Communal violence and farmer-herder Introduction conflicts a. Pastoralism, transhumance and d. Conflict prevention and resolution migration Recommendations b. Challenges facing pastoralists Loss of pasture land and blockage of Chapter 4: THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF transhumance routes MAURITANIA p.49-57 Political (under-)representation and Introduction passivity a. Pastoralism and transhumance in Climate change and adaptation Mauritania Veterinary services b. Challenges facing pastoralists Education Water scarcity c. Security challenges and the causes and Shortages of pasture and animal feed in the drivers of conflict dry season Farmer-herder relations Challenges relating to cross-border Cattle rustling transhumance: The spread of terrorism to Burkina Faso Mauritania-Mali d. Conflict prevention and resolution Pastoralists and forest guards in Mali Recommendations Mauritania-Senegal c. Security challenges and the causes and Chapter 2: THE REPUBLIC OF GUINEA p.31- drivers of conflict 38 The terrorist threat Introduction Armed robbery a. -

REGIS-AG) Quarterly Report (FY15/Q3)

Resilience and Economic Growth in the Sahel – Accelerated Growth (REGIS-AG) Quarterly Report (FY15/Q3) 1 APRIL TO 3O JUNE 2015 Prepared for review_________________________________________________________________ by the United States Agency for International Development under USAID Contract No. AID-625-C-REGIS-AG14-00001, Quarterly Resilience Report, and 1 AprilEconomic – 30 June Growth 2015 (Contractin the Sahel No. AID-625-C-– Accelerated14-00001) Growth (REGIS- AG) Project, implemented by Cultivating New Frontiers in Agriculture (CNFA). 1 Resilience and Economic Growth in the Sahel – Accelerated Growth (REGIS-AG) Project QUARTERLY REPORT (FY15/Q3) 1 APRIL TO 3O JUNE 2015 Submitted by: Cultivating New Frontiers in Agriculture (CNFA) USAID Contract No. AID-625-C-14-00001 Implemented by CNFA Submitted to: Camilien Saint-Cyr COR USAID/Senegal Regional Mission Submitted on 1 August 2015 DISCLAIMER The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Agency for International Development or the United States Government. _________________________________________________________________ REGIS-AG Quarterly Report, 1 April – 30 June 2015 (Contract No. AID-625-C-14-00001) 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Contents ACRONYMS ........................................................................................................................................ 4 1.0 BACKGROUND ....................................................................................................................... 5 2.0 OVERVIEW ............................................................................................................................. -

NIGER: Carte Administrative NIGER - Carte Administrative

NIGER - Carte Administrative NIGER: Carte administrative Awbari (Ubari) Madrusah Légende DJANET Tajarhi /" Capital Illizi Murzuq L I B Y E !. Chef lieu de région ! Chef lieu de département Frontières Route Principale Adrar Route secondaire A L G É R I E Fleuve Niger Tamanghasset Lit du lac Tchad Régions Agadez Timbuktu Borkou-Ennedi-Tibesti Diffa BARDAI-ZOUGRA(MIL) Dosso Maradi Niamey ZOUAR TESSALIT Tahoua Assamaka Tillabery Zinder IN GUEZZAM Kidal IFEROUANE DIRKOU ARLIT ! BILMA ! Timbuktu KIDAL GOUGARAM FACHI DANNAT TIMIA M A L I 0 100 200 300 kms TABELOT TCHIROZERINE N I G E R ! Map Doc Name: AGADEZ OCHA_SitMap_Niger !. GLIDE Number: 16032013 TASSARA INGALL Creation Date: 31 Août 2013 Projection/Datum: GCS/WGS 84 Gao Web Resources: www.unocha..org/niger GAO Nominal Scale at A3 paper size: 1: 5 000 000 TILLIA TCHINTABARADEN MENAKA ! Map data source(s): Timbuktu TAMAYA RENACOM, ARC, OCHA Niger ADARBISNAT ABALAK Disclaimers: KAOU ! TENIHIYA The designations employed and the presentation of material AKOUBOUNOU N'GOURTI I T C H A D on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion BERMO INATES TAKANAMATAFFALABARMOU TASKER whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations BANIBANGOU AZEY GADABEDJI TANOUT concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area ABALA MAIDAGI TAHOUA Mopti ! or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its YATAKALA SANAM TEBARAM !. Kanem WANZERBE AYOROU BAMBAYE KEITA MANGAIZE KALFO!U AZAGORGOULA TAMBAO DOLBEL BAGAROUA TABOTAKI TARKA BANKILARE DESSA DAKORO TAGRISS OLLELEWA -

13 to 17/04/2010 Logistics Capacity Assessment Mission – Diffa & Zinder

13 to 17/04/2010 Logistics Capacity Assessment Mission – Diffa & Zinder (NIGER) Participants : Yann Ilboudo, Logistics Officer Dardaou Chaibou , Logistics Assistant Saidou Kabidou , Coordonateur Régional du programme PAM région de Diffa Laouali Gambo Souna Mahamane , Coordonateur Régional du programme PAM région de Zinder 1. Context of the mission : Due to a poor harvest in the Sahel Region (most affected countries are Chad and Niger and to a lesser extent Burkina Faso, Nigeria (Northern Sates), Cameroon (Northern region) and Mali (East)) which has put some two million people in Niger at immediate risk of severe hunger, WFP is scaling up its food and nutrition activities through its protracted relief and recovery operation (PRRO) 10611.0 “Improving the nutritional status and reinforcing livelihoods of vulnerable populations in Niger”. This will allow WFP to increase the number of people assisted from 941,000 to 2,448,000 by providing an additional 79,927 MT of food until the end of 2010. WFP also intend to deliver food to Chad population affected by the drought trough the Zinder-Diffa-Nguigmi- Chad Corridor. In such a context, WFP is preparing a response to this emergency situation; a strong augmentation of the logistics capacities (Storage, Transport and Staffing) in Zinder and Diffa is necessary. 2. Mission main objectives : Assess the corridor (Diffa - Nguigmi - Chad border) infrastructure Identify potential reliable commercial transporters in Diffa Identify potential storage space in Nguigmi Prepare a construction plan for the Logistics Hub in Diffa Prepare a construction plan for the future Logistics Hub in Zinder Identify the possibilities for water and electricity supply for Zinder Hub Identify potential/possible space for the erection of Rubhall in Gouré, Mainé- Soroa and Magaria departments identified for prepositioning of food distribution Assess the actual storage capacity in Zinder Region Page 1/12 4/21/2010 3. -

FINAL REPORT of the Terminal Evaluation of the Niger COGERAT Project PIMS 2294 Sustainable Co-Management of the Natural Resources of the Air-Ténéré Complex

FINAL REPORT of the Terminal Evaluation of the Niger COGERAT project PIMS 2294 Sustainable Co-Management of the Natural Resources of the Air-Ténéré Complex Co- gestion des Ressources de l'Aïr et du Ténéré Evaluation Team: Juliette BIAO KOUDENOUKPO, Team Leader, International Consultant Pierre NIGNON, National Consultant Draft Completed in July 2013 Original in FR + EN Translation reviewed and ‘UNDP-GEF-streamlined’ on 16 Dec 2014 STREAMLINING Project Title Sustainable Co-Management of the Natural Resources of the Air- Ténéré Complex (COGERAT)1 Concept Paper/PDF B proposal (PIF- GEF Project ID PIMS # 13-Nov-2003 2380 equivalent) UNDP-GEF PIMS # 2294 CEO Endorsement Date 14-Jun-2006 ATLAS Business Unit, NER10 / 00044111 / 00051709 PRODOC Signature Date 22-Aug-2006 Award # Proj. ID: Country(ies): Niger Date project manager hired: No info. Region: Africa Inception Workshop date: No info. Focal Area: Land Degradation / Multiple Planned planed closing date: Aug-2012 Trust Fund [indicate GEF GEF Trust Fund If revised, proposed op. closing date: Aug-2013 TF, LDCF, SCCF, NPIF] GEF Focal Area Strategic OP15 (Land Degradation / Sustainable Actual operational closing date (given TE 31-Dec-2014 Objective Land Management – of GEF3) harmonisation and mgt response finalisation) Exec. Agent / Implementing 2 Partner: Ministry in charge of the environment portfolio Decentralised authorities, particularly Communes and local communities, users of the Reserve, occupational groups and NGOs, Land Commissions, traditional chiefs, other opinion leaders, the Regional Governorate and decentralised technical services. In addition, there is the Ministry for Water and the Environment (MH/E) Other Partners: (providing the institutional basis of the project), UNDP as the Implementing Agency for the Global Environment Facility (GEF), the Technical and Financial partners, the Steering Committee, the Partners’ Forum, the management unit and operational units of COGERAT, the office of the Aïr and Ténéré Nature Reserve, and the Scientific Committee. -

Core Functions / Responsibilities

Position Title : Consultant - Local Development and DDR North Niger Duty Station : Niamey, Niger Classification : Consultant, Grade Other Type of Appointment : Consultant, 2 months Estimated Start Date : As soon as possible Closing Date : 01 March 2017 THE POSTING HAS BEEN ALREADY CLOSED. PLEASE DO NOT APPLY. Established in 1951, IOM is a Related Organization of the United Nations, and as the leading UN agency in the field of migration, works closely with governmental, intergovernmental and non-governmental partners. IOM is dedicated to promoting humane and orderly migration for the benefit of all. It does so by providing services and advice to governments and migrants. Context: Under the direct supervision of MRRM program manager and the overall supervision of the IOM Chief of Mission, the consultant will work mainly on two axes: (i) draft a feasibility and implementation strategy of the Agadez regional development plan (PDR) for 2016-2020 covering the Bilma-Dirkou-Séguedine corridor in the extreme northern region of Niger (ii) in the target area, identify possible economic alternatives for migrants smugglers. The consultancy will last five weeks: three weeks in the field - one week in Niamey and two weeks in Agadez region to consult with local actors - and two weeks to draft the final report. The above-mentioned activities are part of the MIRAA project, financed by the Dutch government. The project aims to contribute to the strengthening of the Government management and governance of migration and to ensure the protection of migrants in an area with limited humanitarian presence. Core Functions / Responsibilities: 1. Draft a feasibility and implementation strategy of the Agadez Regional Development Plan (PDR) for 2016-2020 covering the Bilma-Dirkou-Séguedine corridor. -

Caught in the Middle a Human Rights and Peace-Building Approach to Migration Governance in the Sahel

Caught in the middle A human rights and peace-building approach to migration governance in the Sahel Fransje Molenaar CRU Report Jérôme Tubiana Clotilde Warin Caught in the middle A human rights and peace-building approach to migration governance in the Sahel Fransje Molenaar Jérôme Tubiana Clotilde Warin CRU Report December 2018 December 2018 © Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’. Cover photo: © Jérôme Tubiana. Unauthorized use of any materials violates copyright, trademark and / or other laws. Should a user download material from the website or any other source related to the Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’, or the Clingendael Institute, for personal or non-commercial use, the user must retain all copyright, trademark or other similar notices contained in the original material or on any copies of this material. Material on the website of the Clingendael Institute may be reproduced or publicly displayed, distributed or used for any public and non-commercial purposes, but only by mentioning the Clingendael Institute as its source. Permission is required to use the logo of the Clingendael Institute. This can be obtained by contacting the Communication desk of the Clingendael Institute ([email protected]). The following web link activities are prohibited by the Clingendael Institute and may present trademark and copyright infringement issues: links that involve unauthorized use of our logo, framing, inline links, or metatags, as well as hyperlinks or a form of link disguising the URL. About the authors Fransje Molenaar is a Senior Research Fellow with Clingendael’s Conflict Research Unit, where she heads the Sahel/Libya research programme. She specializes in the political economy of (post-) conflict countries, organized crime and its effect on politics and stability. -

Agadez FAITS ET CHIFFRES

CICR FAITS ET CHIFFRES Janvier- juin 2014 Agadez CICR/ François Thérrien CICR/ François Les activités du CICR dans les régions d’Agadez et Tahoua Entre Janvier et juin 2014, le CICR a poursuivi son action humanitaire dans la région d’Agadez et le nord de la région de Tahoua en vue de soutenir le relèvement des populations. Ainsi, en collaboration avec la Croix-Rouge nigérienne (CRN), le CICR a : SÉCURITE ÉCONOMIQUE Cash For Work EAU ET HABITAT Soutien à l’élevage y réhabilité 31 km de pistes rurales en Commune de Tillia (région de Tahoua) collaboration avec le service technique y vacciné 494 565 têtes d’animaux et traité du génie rural d’Agadez et la Croix- y construit un nouveau puits et réhabilité 143 048 au profit de 12 365 ménages de Rouge nigérienne des communes de celui qui existe à In Izdane, village situé pasteurs dans l’ensemble des communes Tabelot et Timia. Exécutée sous forme de à plus 130 km au sud-ouest du chef-lieu de Tchirozerine, Dabaga, Tabelot, Timia, Cash for work, cette activité a permis de de la commune. Ce projet vise à répondre Iférouane, Gougaram, Dannat et Agadez désenclaver quelques villages des chefs au besoin en eau de plus de 1200 commune en collaboration avec la lieux des communes de Timia et Tabelot et bénéficiaires et de leur cheptel; direction régionale de l’élevage et le va permettre aux maraîchers d’acheminer cabinet privé Tattrit vêt ; facilement leurs produits au niveau des y racheté 60 kg de semences de luzerne marchés. 280 ménages vulnérables ont SANTE auprès des producteurs pilotes et bénéficié de sommes d’argent qui ont redistribué à 200 nouveaux ménages agro permis d’accroître leur revenu.