Evaluation Report Agadez Emergency Health Project Care International Pn- 40

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NIGER: Carte Administrative NIGER - Carte Administrative

NIGER - Carte Administrative NIGER: Carte administrative Awbari (Ubari) Madrusah Légende DJANET Tajarhi /" Capital Illizi Murzuq L I B Y E !. Chef lieu de région ! Chef lieu de département Frontières Route Principale Adrar Route secondaire A L G É R I E Fleuve Niger Tamanghasset Lit du lac Tchad Régions Agadez Timbuktu Borkou-Ennedi-Tibesti Diffa BARDAI-ZOUGRA(MIL) Dosso Maradi Niamey ZOUAR TESSALIT Tahoua Assamaka Tillabery Zinder IN GUEZZAM Kidal IFEROUANE DIRKOU ARLIT ! BILMA ! Timbuktu KIDAL GOUGARAM FACHI DANNAT TIMIA M A L I 0 100 200 300 kms TABELOT TCHIROZERINE N I G E R ! Map Doc Name: AGADEZ OCHA_SitMap_Niger !. GLIDE Number: 16032013 TASSARA INGALL Creation Date: 31 Août 2013 Projection/Datum: GCS/WGS 84 Gao Web Resources: www.unocha..org/niger GAO Nominal Scale at A3 paper size: 1: 5 000 000 TILLIA TCHINTABARADEN MENAKA ! Map data source(s): Timbuktu TAMAYA RENACOM, ARC, OCHA Niger ADARBISNAT ABALAK Disclaimers: KAOU ! TENIHIYA The designations employed and the presentation of material AKOUBOUNOU N'GOURTI I T C H A D on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion BERMO INATES TAKANAMATAFFALABARMOU TASKER whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations BANIBANGOU AZEY GADABEDJI TANOUT concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area ABALA MAIDAGI TAHOUA Mopti ! or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its YATAKALA SANAM TEBARAM !. Kanem WANZERBE AYOROU BAMBAYE KEITA MANGAIZE KALFO!U AZAGORGOULA TAMBAO DOLBEL BAGAROUA TABOTAKI TARKA BANKILARE DESSA DAKORO TAGRISS OLLELEWA -

Caught in the Middle a Human Rights and Peace-Building Approach to Migration Governance in the Sahel

Caught in the middle A human rights and peace-building approach to migration governance in the Sahel Fransje Molenaar CRU Report Jérôme Tubiana Clotilde Warin Caught in the middle A human rights and peace-building approach to migration governance in the Sahel Fransje Molenaar Jérôme Tubiana Clotilde Warin CRU Report December 2018 December 2018 © Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’. Cover photo: © Jérôme Tubiana. Unauthorized use of any materials violates copyright, trademark and / or other laws. Should a user download material from the website or any other source related to the Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’, or the Clingendael Institute, for personal or non-commercial use, the user must retain all copyright, trademark or other similar notices contained in the original material or on any copies of this material. Material on the website of the Clingendael Institute may be reproduced or publicly displayed, distributed or used for any public and non-commercial purposes, but only by mentioning the Clingendael Institute as its source. Permission is required to use the logo of the Clingendael Institute. This can be obtained by contacting the Communication desk of the Clingendael Institute ([email protected]). The following web link activities are prohibited by the Clingendael Institute and may present trademark and copyright infringement issues: links that involve unauthorized use of our logo, framing, inline links, or metatags, as well as hyperlinks or a form of link disguising the URL. About the authors Fransje Molenaar is a Senior Research Fellow with Clingendael’s Conflict Research Unit, where she heads the Sahel/Libya research programme. She specializes in the political economy of (post-) conflict countries, organized crime and its effect on politics and stability. -

Local Governance Opportunities for Sustainable Migration Management in Agadez

Local governance opportunities for sustainable migration management in Agadez Fransje Molenaar CRU Report Anca-Elena Ursu Bachirou Ayouba Tinni Supported by: Local governance opportunities for sustainable migration management in Agadez Fransje Molenaar Anca-Elena Ursu Bachirou Ayouba Tinni CRU Report October 2017 October 2017 © Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’. Cover photo: Men sitting on a bench at the Agadez Market. © Boris Kester / traveladventures.org Unauthorised use of any materials violates copyright, trademark and / or other laws. Should a user download material from the website or any other source related to the Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’, or the Clingendael Institute, for personal or non-commercial use, the user must retain all copyright, trademark or other similar notices contained in the original material or on any copies of this material. Material on the website of the Clingendael Institute may be reproduced or publicly displayed, distributed or used for any public and non-commercial purposes, but only by mentioning the Clingendael Institute as its source. Permission is required to use the logo of the Clingendael Institute. This can be obtained by contacting the Communication desk of the Clingendael Institute ([email protected]). The following web link activities are prohibited by the Clingendael Institute and may present trademark and copyright infringement issues: links that involve unauthorized use of our logo, framing, inline links, or metatags, as well as hyperlinks or a form of link disguising the URL. About the authors Fransje Molenaar is a research fellow at the Clingendael Institute’s Conflict Research Unit Anca-Elena Ursu is a research assistant at the Clingendael Institute’s Conflict Research Unit Bachirou Ayouba Tinni is a PhD student at the University of Niamey The Clingendael Institute P.O. -

Assessment of Chronic Food Insecurity in Niger

Assessment of Chronic Food Insecurity in Niger Analysis Coordination March 2019 Assessment of Chronic Food Insecurity in Niger 2019 About FEWS NET Created in response to the 1984 famines in East and West Africa, the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) provides early warning and integrated, forward-looking analysis of the many factors that contribute to food insecurity. FEWS NET aims to inform decision makers and contribute to their emergency response planning; support partners in conducting early warning analysis and forecasting; and provide technical assistance to partner-led initiatives. To learn more about the FEWS NET project, please visit www.fews.net. Acknowledgements This publication was prepared under the United States Agency for International Development Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) Indefinite Quantity Contract, AID-OAA-I-12-00006. The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. Recommended Citation FEWS NET. 2019. Assessment of Chronic Food Insecurity in Niger. Washington, DC: FEWS NET. Famine Early Warning Systems Network ii Assessment of Chronic Food Insecurity in Niger 2019 Table of Contents Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Background ............................................................................................................................................................................. -

Art5-Requestsummary-Niger-EN.Pdf

APLC/MSP.15/2016/WP.1 Meeting of the States Parties to the Convention on 4 October 2016 the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production English and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines and on Their Original: French Destruction Fifteenth Meeting Santiago, 28 November-2 December 2016 Item 10 (b) of the provisional agenda Consideration of the general status and operation of the Convention Clearing mined areas: conclusions and recommendations related to the mandate of the Committee on Article 5 Implementation Request for extension of the deadline for completing the destruction of anti-personnel mines in accordance with article 5 of the Convention Submitted by Niger 1. Niger ratified the Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines and on Their Destruction on 23 March 1999; the Convention entered into force for Niger on 1 September 1999. Under article 5 of the Convention, Niger had until 1 September 2009 to confirm whether anti-personnel mines were present in the areas indicated and, if so, to destroy all such mines detected there. 2. Since February 2007, Niger has faced renewed security threats as a result of violent acts carried out by an armed movement. In the course of these acts, mines have been laid, making access and movement difficult for the local population and development partners. 3. In 2011, following a change in the security situation after the conflict in the north of the country and the Libyan crisis, Niger carried out an assessment mission; in May 2014, it conducted non-technical and technical surveys that revealed the presence of an ID51 anti- personnel minefield in the north of the Agadez region, in the department of Bilma (Dirkou), on the military post of Madama. -

Farming Systems and Food Security in Africa

Farming Systems and Food Security in Africa Knowledge of Africa’s complex farming systems, set in their socio-economic and environmental context, is an essential ingredient to developing effective strategies for improving food and nutrition security. This book systematically and comprehensively describes the characteristics, trends, drivers of change and strategic priorities for each of Africa’s fifteen farming systems and their main subsystems. It shows how a farming systems perspective can be used to identify pathways to household food security and pov- erty reduction, and how strategic interventions may need to differ from one farming system to another. In the analysis, emphasis is placed on understanding farming systems drivers of change, trends and stra- tegic priorities for science and policy. Illustrated with full-colour maps and photographs throughout, the volume provides a comprehen- sive and insightful analysis of Africa’s farming systems and pathways for the future to improve food and nutrition security. The book is an essential follow-up to the seminal work Farming Systems and Poverty by Dixon and colleagues for the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations and the World Bank, published in 2001. John Dixon is Principal Adviser Research & Program Manager, Cropping Systems and Economics, Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR), Canberra, Australia. Dennis Garrity is Senior Fellow at the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF), based in Nairobi, Kenya, UNCCD Drylands Ambassador, and Chair of the EverGreen Agriculture Partnership. Jean-Marc Boffa is Director of Terra Sana Projects and Associate Fellow of the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF), Nairobi, Kenya. Timothy Olalekan Williams is Regional Director for Africa at the International Water Management Institute (IWMI), based in Accra, Ghana. -

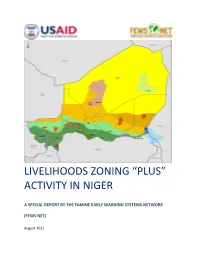

Livelihoods Zoning “Plus” Activity in Niger

LIVELIHOODS ZONING “PLUS” ACTIVITY IN NIGER A SPECIAL REPORT BY THE FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS NETWORK (FEWS NET) August 2011 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................. 4 National Livelihoods Zones Map ................................................................................................................... 6 Livelihoods Highlights ................................................................................................................................... 7 National Seasonal Calendar .......................................................................................................................... 9 Rural Livelihood Zones Descriptions ........................................................................................................... 11 Zone 1: Northeast Oases: Dates, Salt and Trade ................................................................................... 11 Zone 2: Aïr Massif Irrigated Gardening ................................................................................................ 14 Zone 3 : Transhumant and Nomad Pastoralism .................................................................................... 17 Zone 4: Agropastoral Belt ..................................................................................................................... -

Beyond the 'Wild West': the Gold Rush in Northern Niger

Briefing Paper June 2017 BEYOND THE ‘WILD WEST’ The Gold Rush in Northern Niger Mathieu Pellerin Beyond the ‘Wild West’ 1 Credits and contributors Series editor: Matt Johnson About the author ([email protected]) Mathieu Pellerin is an Associate Researcher for the Africa Programme at the Institut Copy-editor: Alex Potter français des relations internationales and an expert on political and security issues ([email protected]) in the Sahel and Maghreb regions. As part of his research and consultancy for both Proofreader: Stephanie Huitson national and international organizations he regularly travels to Mali, Niger, Burkina ([email protected]) Faso, and Mauritania, as well as Libya, Tunisia, and Morocco. Since June 2015 he has also been Special Adviser on religious dialogue for the Centre for Humanitarian Cartography: Jillian Luff Dialogue. He has two master’s degrees (in Political Science and Economic Sciences), (www.mapgrafix.com) and currently teaches on the crisis in the Sahel at Sciences Po in Lille. Design and layout: Rick Jones ([email protected]) Acknowledgements The author would like to extend his sincere thanks to Dr Ines Kohl and Savannah de Tessières for their insightful peer reviews. Matt Johnson and Alex Potter also have to be thanked for their checking and editing work. Front cover photo A miner reaches for his metal detector in the Djado region, northern Niger. Source: Djibo Issifou, 2016. 2 SANA Briefing Paper June 2017 Overview Introduction One of the many stories recounting how This Briefing Paper examines how the gold rush in northern gold mining began in northern Niger in Niger has affected the security, political, and socio-economic April 2014 tells of a Tubu camel herder dynamics of this sensitive region. -

Assessment of Chronic Food Insecurity in Niger

Assessment of Chronic Food Insecurity in Niger Analysis Coordination March 2019 This publication was prepared under the United States Agency for International Development Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) Indefinite Quantity Contract, AID-OAA-I-12-00006. The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. Assessment of Chronic Food Insecurity in Niger 2019 Table of Contents Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Background .............................................................................................................................................................................. 1 Summary of Classification Conclusions ................................................................................................................................... 1 Food Consumptions Quality .................................................................................................................................................... 3 Food Consumption Quantity ................................................................................................................................................... 4 Nutrition ................................................................................................................................................................................. -

Report for Niger

NIGER ARTICLE 5 DEADLINE: 31 DECEMBER 2016 (EXTENSION REQUESTED UNTIL 31 DECEMBER 2020) PROGRAMME PERFORMANCE For 2015 For 2014 Problem understood 8 7 Target date for completion of mine clearance 4 5 Targeted clearance 8 8 Efficient clearance 6 6 National funding of programme 6 6 Timely clearance 5 3 Land release system in place 6 6 National mine action standards 6 6 Reporting on progress 5 7 Improving performance 8 8 PERFORMANCE SCORE: AVERAGE 6.2 6.2 128 STATES PARTIES NIGER PERFORMANCE COMMENTARY Niger initiated clearance in 2015 and took steps to better understand the extent of its anti-personnel mine threat. It submitted its second Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention (APMBC) Article 5 deadline extension request extremely late, without a detailed workplan or sufficient information to justify its request for a further period of five years to clear relatively small contamination. RECOMMENDATIONS FOR ACTION ■ Niger should provide a detailed workplan to accompany its revised second Article 5 extension request, with benchmarks against which progress can be assessed. ■ Niger should provide regular updates on progress in clearance and the extent of contamination remaining. It should also inform APMBC states parties of the discovery of any new contamination from anti-personnel mines, victim-activated improvised explosive devices (IEDs) and report on the location of all suspected or confirmed mined areas under its jurisdiction or control. ■ Niger should accept offers of assistance in a timely manner, which would improve the speed and efficiency of clearance and enable completion far earlier than 2020. ■ Niger should develop a resource mobilisation plan to meet funding needs beyond expected national contributions. -

Caught in the Middle a Human Rights and Peace-Building Approach to Migration Governance in the Sahel

Caught in the middle A human rights and peace-building approach to migration governance in the Sahel Fransje Molenaar CRU Report Jérôme Tubiana Clotilde Warin Caught in the middle A human rights and peace-building approach to migration governance in the Sahel Fransje Molenaar Jérôme Tubiana Clotilde Warin CRU Report December 2018 December 2018 © Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’. Cover photo: © Jérôme Tubiana. Unauthorized use of any materials violates copyright, trademark and / or other laws. Should a user download material from the website or any other source related to the Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’, or the Clingendael Institute, for personal or non-commercial use, the user must retain all copyright, trademark or other similar notices contained in the original material or on any copies of this material. Material on the website of the Clingendael Institute may be reproduced or publicly displayed, distributed or used for any public and non-commercial purposes, but only by mentioning the Clingendael Institute as its source. Permission is required to use the logo of the Clingendael Institute. This can be obtained by contacting the Communication desk of the Clingendael Institute ([email protected]). The following web link activities are prohibited by the Clingendael Institute and may present trademark and copyright infringement issues: links that involve unauthorized use of our logo, framing, inline links, or metatags, as well as hyperlinks or a form of link disguising the URL. About the authors Fransje Molenaar is a Senior Research Fellow with Clingendael’s Conflict Research Unit, where she heads the Sahel/Libya research programme. She specializes in the political economy of (post-) conflict countries, organized crime and its effect on politics and stability. -

Downloaded from Afsis Website

REPUBLIC OF NIGER FRATERNITY – LABOR - PROGRESS MINISTRY OF FINANCE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF STATISTICS 2011 National Survey on Household Living Conditions and Agriculture (ECVM/A-2011) BASIC INFORMATION DOCUMENT October 2013 ACRONYMS ECVM/A National Survey on Living Conditions and Agriculture 2011 ENBC National Survey on Household Budget and Consumption GDP Gross Domestic Product INS National Institute of Statistics LSMS-ISA Living Standards Measurement Study – Integrated Surveys on Agriculture MDG Millennium Development Goal QUIBB Core Welfare Indicator Questionnaire ZD Enumeration area CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 1 2. CHARACTERISTICS OF THE SURVEY ............................................................................ 2 2.1. Brief Introduction to the Survey and the Household Questionnaire – first visit ............. 2 2.2. DESCRIPTION OF THE SECOND VISIT QUESTIONNAIRE ................................... 3 2.3 Description of the agriculture and livestock questionnaire – First Visit .......................... 3 2.4 description of the agriculture and livestock questionnaire – second visit ........................ 3 2.5 description of the community questionnaire .................................................................... 3 3. SAMPLING ........................................................................................................................... 3 4 PILOT TEST .........................................................................................................................