Roadmap for Sustainable Migration Management in Agadez

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

32 Mohamadou Tchinta

1 LASDEL Laboratoire d’études et recherches sur les dynamiques sociales et le développement local _________ BP 12901, Niamey, Niger – tél. (227) 72 37 80 BP 1383, Parakou, Bénin – tél. (229) 61 16 58 Observatoire de la décentralisation au Niger (enquête de référence 2004) Les pouvoirs locaux dans la commune de Tchintabaraden Abdoulaye Mohamadou Enquêteurs : Afélane Alfarouk et Ahmoudou Rhissa février 05 Etudes et Travaux n° 32 Financement FICOD (KfW) 2 Sommaire Introduction 3 Les Kel Dinnig : de la confédération aux communes 3 Objectifs de l’étude et méthodologie 4 1. Le pouvoir local et ses acteurs 6 1.1. Histoire administrative de l’arrondissement et naissance d’un centre urbain 6 1.2. Les acteurs de l’arène politique locale 7 2. Le découpage de l’arrondissement de Tchintabaraden 19 2.1. Logiques territoriale et logiques sociales 19 2.2. Le choix des bureaux de vote 22 2.3. Les stratégies des partis politiques pour le choix des conseillers 23 2.4. La décentralisation vue par les acteurs 23 3. L’organisation actuelle des finances locales 25 3.1. Les projets de développement 25 3. 2. Le budget de l’arrondissement 26 Conclusion 33 3 Introduction Les Kel Dinnig : de la confédération aux communes L’arrondisssement de Tchintabaraden correspondait avant la création de celui d’Abalak en 1992 à l’espace géographique et social des Touareg Iwillimenden ou Kel Dinnig. Après la révolte de Kaocen en 1916-1917 et son anéantissement par les troupes coloniales françaises, l’aménokalat des Iwilimenden fut disloqué et réparti en plusieurs groupements. Cette technique de diviser pour mieux régner, largement utilisée par l’administration coloniale, constitue le point de départ du découpage administratif pour les populations de cette région. -

Evaluation Report Agadez Emergency Health Project Care International Pn- 40

FINAL EVALUATION REPORT AGADEZ EMERGENCY HEALTH PROJECT CARE INTERNATIONAL PN- 40 James C. Setzer, MPH Shannon M. Mason, MPH Seydou Abdou Issoufou Mato August 1999 Acknowledgments: The evaluation team would like to take this opportunity to congratulate the Project PN-40 for what is clearly a job well done! They have worked tirelessly to provide important health services to communities that, due to many factors, previously had none. They have done so by using their hands and feet, heads and most importantly their hearts. The results described here would not have been possible if the entire team had not been truly dedicated to improving the health and well-being of the population in their target areas. They have clearly believed in what they set out to do and its importance. In conditions such as these, technical know-how alone is not sufficient to get the job done. For their efforts and dedication then they should be congratulated and thanked. Thanked on behalf of CARE for representing their organization and its mission so well and on behalf of the women and children of northern Niger who will not suffer from preventable illness and death. The evaluation team sincerely hopes that their efforts may in some small way be seen as a contribution to this effort. It is important, also, to thank a number of persons for their input and assistance to this final evaluation exercise. The CARE/Niger country team under the leadership of both Jan Schollert and Douglas Steinberg should be acknowledged for their assistance in putting the evaluation team together and facilitating their work. -

Dynamique Des Conflits Et Médias Au Niger Et À Tahoua Revue De La Littérature

Dynamique des Conflits et Médias au Niger et à Tahoua Revue de la littérature Décembre 2013 Charline Burton Rebecca Justus Contacts: Charline Burton Moutari Aboubacar Spécialiste Conception, Suivi et Coordonnateur National des Evaluation – Afrique de l’Ouest Programmes - Niger Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire [email protected] + 227 9649 00 39 [email protected] +225 44 47 24 57 +227 90 60 54 96 Dynamique des conflits et Médias au Niger et à Tahoua | PAGE 2 Table des matières 1. Résumé exécutif ...................................................................................................... 4 Contexte ................................................................................................. 4 Objectifs et méthodologie ........................................................................ 4 Résultats principaux ............................................................................... 4 2. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 7 2.1 Contexte de la revue de littérature ............................................................... 7 2.2 Méthodologie et questions de recherche ....................................................... 7 3. Contexte général du Niger .................................................................................. 10 3.1 Démographie ............................................................................................. 10 3.2 Situation géographique et géostratégique ............................................ -

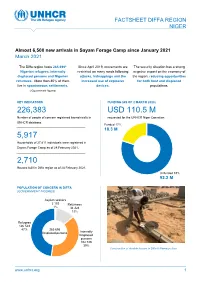

UNHCR Niger Operation UNHCR Database

FACTSHEET DIFFA REGION NIGER Almost 6,500 new arrivals in Sayam Forage Camp since January 2021 March 2021 NNNovember The Diffa region hosts 265,696* Since April 2019, movements are The security situation has a strong Nigerian refugees, internally restricted on many roads following negative impact on the economy of displaced persons and Nigerien attacks, kidnappings and the the region, reducing opportunities returnees. More than 80% of them increased use of explosive for both host and displaced live in spontaneous settlements. devices. populations. (*Government figures) KEY INDICATORS FUNDING (AS OF 2 MARCH 2020) 226,383 USD 110.5 M Number of people of concern registered biometrically in requested for the UNHCR Niger Operation UNHCR database. Funded 17% 18.3 M 5,917 Households of 27,811 individuals were registered in Sayam Forage Camp as of 28 February 2021. 2,710 Houses built in Diffa region as of 28 February 2021. Unfunded 83% 92.2 M the UNHCR Niger Operation POPULATION OF CONCERN IN DIFFA (GOVERNMENT FIGURES) Asylum seekers 2 103 Returnees 1% 34 324 13% Refugees 126 543 47% 265 696 Displaced persons Internally Displaced persons 102 726 39% Construction of durable houses in Diffa © Ramatou Issa www.unhcr.org 1 OPERATIONAL UPDATE > Niger - Diffa / March 2021 Operation Strategy The key pillars of the UNHCR strategy for the Diffa region are: ■ Ensure institutional resilience through capacity development and support to the authorities (locally elected and administrative authorities) in the framework of the Niger decentralisation process. ■ Strengthen the out of camp policy around the urbanisation program through sustainable interventions and dynamic partnerships including with the World Bank. -

Pastoralism and Security in West Africa and the Sahel

Pastoralism and Security in West Africa and the Sahel Towards Peaceful Coexistence UNOWAS STUDY 1 2 Pastoralism and Security in West Africa and the Sahel Towards Peaceful Coexistence UNOWAS STUDY August 2018 3 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations p.8 Chapter 3: THE REPUBLIC OF MALI p.39-48 Acknowledgements p.9 Introduction Foreword p.10 a. Pastoralism and transhumance UNOWAS Mandate p.11 Pastoral Transhumance Methodology and Unit of Analysis of the b. Challenges facing pastoralists Study p.11 A weak state with institutional constraints Executive Summary p.12 Reduced access to pasture and water Introductionp.19 c. Security challenges and the causes and Pastoralism and Transhumance p.21 drivers of conflict Rebellion, terrorism, and the Malian state Chapter 1: BURKINA FASO p.23-30 Communal violence and farmer-herder Introduction conflicts a. Pastoralism, transhumance and d. Conflict prevention and resolution migration Recommendations b. Challenges facing pastoralists Loss of pasture land and blockage of Chapter 4: THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF transhumance routes MAURITANIA p.49-57 Political (under-)representation and Introduction passivity a. Pastoralism and transhumance in Climate change and adaptation Mauritania Veterinary services b. Challenges facing pastoralists Education Water scarcity c. Security challenges and the causes and Shortages of pasture and animal feed in the drivers of conflict dry season Farmer-herder relations Challenges relating to cross-border Cattle rustling transhumance: The spread of terrorism to Burkina Faso Mauritania-Mali d. Conflict prevention and resolution Pastoralists and forest guards in Mali Recommendations Mauritania-Senegal c. Security challenges and the causes and Chapter 2: THE REPUBLIC OF GUINEA p.31- drivers of conflict 38 The terrorist threat Introduction Armed robbery a. -

NIGER: Carte Administrative NIGER - Carte Administrative

NIGER - Carte Administrative NIGER: Carte administrative Awbari (Ubari) Madrusah Légende DJANET Tajarhi /" Capital Illizi Murzuq L I B Y E !. Chef lieu de région ! Chef lieu de département Frontières Route Principale Adrar Route secondaire A L G É R I E Fleuve Niger Tamanghasset Lit du lac Tchad Régions Agadez Timbuktu Borkou-Ennedi-Tibesti Diffa BARDAI-ZOUGRA(MIL) Dosso Maradi Niamey ZOUAR TESSALIT Tahoua Assamaka Tillabery Zinder IN GUEZZAM Kidal IFEROUANE DIRKOU ARLIT ! BILMA ! Timbuktu KIDAL GOUGARAM FACHI DANNAT TIMIA M A L I 0 100 200 300 kms TABELOT TCHIROZERINE N I G E R ! Map Doc Name: AGADEZ OCHA_SitMap_Niger !. GLIDE Number: 16032013 TASSARA INGALL Creation Date: 31 Août 2013 Projection/Datum: GCS/WGS 84 Gao Web Resources: www.unocha..org/niger GAO Nominal Scale at A3 paper size: 1: 5 000 000 TILLIA TCHINTABARADEN MENAKA ! Map data source(s): Timbuktu TAMAYA RENACOM, ARC, OCHA Niger ADARBISNAT ABALAK Disclaimers: KAOU ! TENIHIYA The designations employed and the presentation of material AKOUBOUNOU N'GOURTI I T C H A D on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion BERMO INATES TAKANAMATAFFALABARMOU TASKER whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations BANIBANGOU AZEY GADABEDJI TANOUT concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area ABALA MAIDAGI TAHOUA Mopti ! or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its YATAKALA SANAM TEBARAM !. Kanem WANZERBE AYOROU BAMBAYE KEITA MANGAIZE KALFO!U AZAGORGOULA TAMBAO DOLBEL BAGAROUA TABOTAKI TARKA BANKILARE DESSA DAKORO TAGRISS OLLELEWA -

2 Etude Sur La Problématique De L'accès Aux Ressources Pastorales

Etude sur la Problématique de l’accès aux ressources pastorales dans le Département de Tesker 1 Etude sur la Problématique de l’accès aux ressources pastorales 2 dans le Département de Tesker Réalisation Etude sur la Problématique de l’accès aux ressources pastorales dans le Département de Tesker 3 Sommaire Etude sur la Problématique de l’accès aux ressources pastorales 4 dans le Département de Tesker Introduction Générale 1. Contexte Le Niger est un pays à vocation essentiellement agro-pastorale. L’élevage revêt une importance économique, sociale et culturelle fondamentale, représentant environ 11% du PIB et contribuant à près de 35% au PIB agricole. Cette activité ap- porte une contribution substantielle à l’alimenta- tion des populations. Majoritairement nomade (transhumant), l’éle- vage au Niger repose essentiellement sur l’ex- ploitation extensive des pâturages naturels qui constituent la principale source de fourrage pour le bétail. Cette pratique basée sur la mobilité des troupeaux permet une utilisation judicieuse et opportune du fourrage et de l’eau le long des parcours pastoraux. Malheureusement, ces der- nières décennies, plusieurs facteurs dont, entre autres, la forte croissance démographique et les conditions climatiques, de moins en moins favo- rables, rendent l’accès aux ressources pastorales particulièrement l’eau et le fourrage de plus en plus problématique pour les éleveurs. La pression sur ces ressources naturelles augmente de ma- Etude sur la Problématique de l’accès aux ressources pastorales dans le Département de Tesker 5 nière permanente exerçant ainsi une réelle me- nace sur les pratiques pastorales et la mobilité des troupeaux. Ainsi, en zones agricoles et agropastorales, on assiste à une mise en culture progressive des es- paces habituellement à vocation pastorale, et en zone pastorale on constate, la remontée du front agricole du sud vers le nord. -

Niger Country Brief: Property Rights and Land Markets

NIGER COUNTRY BRIEF: PROPERTY RIGHTS AND LAND MARKETS Yazon Gnoumou Land Tenure Center, University of Wisconsin–Madison with Peter C. Bloch Land Tenure Center, University of Wisconsin–Madison Under Subcontract to Development Alternatives, Inc. Financed by U.S. Agency for International Development, BASIS IQC LAG-I-00-98-0026-0 March 2003 Niger i Brief Contents Page 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Purpose of the country brief 1 1.2 Contents of the document 1 2. PROFILE OF NIGER AND ITS AGRICULTURE SECTOR AND AGRARIAN STRUCTURE 2 2.1 General background of the country 2 2.2 General background of the economy and agriculture 2 2.3 Land tenure background 3 2.4 Land conflicts and resolution mechanisms 3 3. EVIDENCE OF LAND MARKETS IN NIGER 5 4. INTERVENTIONS ON PROPERTY RIGHTS AND LAND MARKETS 7 4.1 The colonial regime 7 4.2 The Hamani Diori regime 7 4.3 The Kountché regime 8 4.4 The Rural Code 9 4.5 Problems facing the Rural Code 10 4.6 The Land Commissions 10 5. ASSESSMENT OF INTERVENTIONS ON PROPERTY RIGHTS AND LAND MARKET DEVELOPMENT 11 6. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 13 BIBLIOGRAPHY 15 APPENDIX I. SELECTED INDICATORS 25 Niger ii Brief NIGER COUNTRY BRIEF: PROPERTY RIGHTS AND LAND MARKETS Yazon Gnoumou with Peter C. Bloch 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 PURPOSE OF THE COUNTRY BRIEF The purpose of the country brief is to determine to which extent USAID’s programs to improve land markets and property rights have contributed to secure tenure and lower transactions costs in developing countries and countries in transition, thereby helping to achieve economic growth and sustainable development. -

FINAL REPORT of the Terminal Evaluation of the Niger COGERAT Project PIMS 2294 Sustainable Co-Management of the Natural Resources of the Air-Ténéré Complex

FINAL REPORT of the Terminal Evaluation of the Niger COGERAT project PIMS 2294 Sustainable Co-Management of the Natural Resources of the Air-Ténéré Complex Co- gestion des Ressources de l'Aïr et du Ténéré Evaluation Team: Juliette BIAO KOUDENOUKPO, Team Leader, International Consultant Pierre NIGNON, National Consultant Draft Completed in July 2013 Original in FR + EN Translation reviewed and ‘UNDP-GEF-streamlined’ on 16 Dec 2014 STREAMLINING Project Title Sustainable Co-Management of the Natural Resources of the Air- Ténéré Complex (COGERAT)1 Concept Paper/PDF B proposal (PIF- GEF Project ID PIMS # 13-Nov-2003 2380 equivalent) UNDP-GEF PIMS # 2294 CEO Endorsement Date 14-Jun-2006 ATLAS Business Unit, NER10 / 00044111 / 00051709 PRODOC Signature Date 22-Aug-2006 Award # Proj. ID: Country(ies): Niger Date project manager hired: No info. Region: Africa Inception Workshop date: No info. Focal Area: Land Degradation / Multiple Planned planed closing date: Aug-2012 Trust Fund [indicate GEF GEF Trust Fund If revised, proposed op. closing date: Aug-2013 TF, LDCF, SCCF, NPIF] GEF Focal Area Strategic OP15 (Land Degradation / Sustainable Actual operational closing date (given TE 31-Dec-2014 Objective Land Management – of GEF3) harmonisation and mgt response finalisation) Exec. Agent / Implementing 2 Partner: Ministry in charge of the environment portfolio Decentralised authorities, particularly Communes and local communities, users of the Reserve, occupational groups and NGOs, Land Commissions, traditional chiefs, other opinion leaders, the Regional Governorate and decentralised technical services. In addition, there is the Ministry for Water and the Environment (MH/E) Other Partners: (providing the institutional basis of the project), UNDP as the Implementing Agency for the Global Environment Facility (GEF), the Technical and Financial partners, the Steering Committee, the Partners’ Forum, the management unit and operational units of COGERAT, the office of the Aïr and Ténéré Nature Reserve, and the Scientific Committee. -

Core Functions / Responsibilities

Position Title : Consultant - Local Development and DDR North Niger Duty Station : Niamey, Niger Classification : Consultant, Grade Other Type of Appointment : Consultant, 2 months Estimated Start Date : As soon as possible Closing Date : 01 March 2017 THE POSTING HAS BEEN ALREADY CLOSED. PLEASE DO NOT APPLY. Established in 1951, IOM is a Related Organization of the United Nations, and as the leading UN agency in the field of migration, works closely with governmental, intergovernmental and non-governmental partners. IOM is dedicated to promoting humane and orderly migration for the benefit of all. It does so by providing services and advice to governments and migrants. Context: Under the direct supervision of MRRM program manager and the overall supervision of the IOM Chief of Mission, the consultant will work mainly on two axes: (i) draft a feasibility and implementation strategy of the Agadez regional development plan (PDR) for 2016-2020 covering the Bilma-Dirkou-Séguedine corridor in the extreme northern region of Niger (ii) in the target area, identify possible economic alternatives for migrants smugglers. The consultancy will last five weeks: three weeks in the field - one week in Niamey and two weeks in Agadez region to consult with local actors - and two weeks to draft the final report. The above-mentioned activities are part of the MIRAA project, financed by the Dutch government. The project aims to contribute to the strengthening of the Government management and governance of migration and to ensure the protection of migrants in an area with limited humanitarian presence. Core Functions / Responsibilities: 1. Draft a feasibility and implementation strategy of the Agadez Regional Development Plan (PDR) for 2016-2020 covering the Bilma-Dirkou-Séguedine corridor. -

Caught in the Middle a Human Rights and Peace-Building Approach to Migration Governance in the Sahel

Caught in the middle A human rights and peace-building approach to migration governance in the Sahel Fransje Molenaar CRU Report Jérôme Tubiana Clotilde Warin Caught in the middle A human rights and peace-building approach to migration governance in the Sahel Fransje Molenaar Jérôme Tubiana Clotilde Warin CRU Report December 2018 December 2018 © Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’. Cover photo: © Jérôme Tubiana. Unauthorized use of any materials violates copyright, trademark and / or other laws. Should a user download material from the website or any other source related to the Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’, or the Clingendael Institute, for personal or non-commercial use, the user must retain all copyright, trademark or other similar notices contained in the original material or on any copies of this material. Material on the website of the Clingendael Institute may be reproduced or publicly displayed, distributed or used for any public and non-commercial purposes, but only by mentioning the Clingendael Institute as its source. Permission is required to use the logo of the Clingendael Institute. This can be obtained by contacting the Communication desk of the Clingendael Institute ([email protected]). The following web link activities are prohibited by the Clingendael Institute and may present trademark and copyright infringement issues: links that involve unauthorized use of our logo, framing, inline links, or metatags, as well as hyperlinks or a form of link disguising the URL. About the authors Fransje Molenaar is a Senior Research Fellow with Clingendael’s Conflict Research Unit, where she heads the Sahel/Libya research programme. She specializes in the political economy of (post-) conflict countries, organized crime and its effect on politics and stability. -

West and Central Africa: Early Warning/Early Action

Emergency appeal n° MDR61005 West and Central Africa: Operations update n° 2 Early Warning/Early 10 May, 2010 Action Period covered by this Ops Update: 1 November 2009-2 April 2010. Appeal target (current): CHF 918,517 (USD 896,114 or EUR 605,283) Appeal coverage: 100%; <click here to go directly to the updated donor response report, here to link to contact details> Appeal history: · This Emergency Appeal was initially launched on 6 August 2009 for CHF 918,517 for 9 months to assist 25,000 beneficiaries. · Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF): CHF 200,000 was allocated from the Federation’s DREF to support this Appeal and related action. · Programme update no. 1 was issued on 19 October, 2009; Period covered: 6 August - 7 October 2009; Appeal target (current): Demo on the use of agricultural tools in Niger/WCAZ CHF 918,517; Appeal coverage: 91%; Summary: Despite the effectiveness of this early warning and early action initiative and the related activities carried out, the flood occurrence in many countries has been very severe due to the fact that the heavy precipitation came at the end of the rainy season often after two months of normal rainy to dry conditions. The location of these rains (in areas with poor urbanization planning) exacerbated an already difficult situation. Based on ongoing updated meteorological reports from the African Centre of Meteorological Application for Development (ACMAD) highlighting heavy precipitations, other countries were covered by the EW-EA appeal. Therefore, some 51 climate risk bulletins for the humanitarian community in West Africa have been disseminated to the National Societies within the zone through the Disaster Management volunteer’s network (93 members of RDRT, 600 members of CDRT and 240 members of NDRT) as early warning for appropriate actions.