Politics of Mega-Events in China's Hong Kong and Macao

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8-Th Session.Indd

INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC ACADEMY REPORT ON THE 8TH INTERNATIONAL SESSION FOR DIRECTORS OF NATIONAL OLYMPIC ACADEMIES 18 – 25 APRIL 2005 ANCIENT OLYMPIA Published by the International Olympic Academy and the International Olympic Committee International Olympic Academy 52, Dimitrios Vikelas Avenue, 152 33 Halandri-Athens, Greece Editor: Assoc. Prof. Konstantinos Georgiadis, IOA Honorary Dean Athens 2006 ISBN: 960-89540-1-0 INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC ACADEMY SPECIAL SUBJECT: THE NATIONAL OLYMPIC ACADEMY: STRUCTURE, OBJECTIVES AND OPERATION ANCIENT OLYMPIA Commemorative Seal of the 8th Session for Directors of NOAs EPHORIA OF THE INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC ACADEMY (2005) President Nikos FILARETOS (IOC Member) Vice-President Isidoros KOUVELOS Dean Konstantinos GEORGIADIS Members Lambis NIKOLAOU (IOC Member) Minos KYRIAKOU Emmanuel KATSIADAKIS Evangelos SOUFLERIS Panayotis KONDOS Leonidas VAROUXIS Georgios FOTINOPOULOS Honorary President Juan Antonio SAMARANCH Honorary Vice-President Nikolaos YALOURIS – 7 – HELLENIC OLYMPIC COMMITTEE President Minos KYRIAKOU 1st Vice-President Isidoros KOUVELOS 2nd Vice-President Spyros ZANNIAS Secretary General Emmanuel KATSIADAKIS Treasurer Pavlos KANELLAKIS Deputy Secretary General Antonios NIKOLOPOULOS Deputy Treasurer Ioannis KARRAS Member ex-offi cio Nikos FILARETOS (IOC Member) Member ex-offi cio Lambis NIKOLAOU (IOC Member) Members Stelios ANGELOUDIS Andreas ARVANITIS Athanassios BELIGRATIS Dimitris DIATHESSOPOULOS Dimitris DIMITROPOULOS Michalis FISSENTZIDIS Andreas FOURAS Vassilis GAGATSIS Christos HATZIATHANASSIOU -

INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC ACADEMY 10Th JOINT

INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC ACADEMY 10th JOINT INTERNATIONAL SESSION FOR PRESIDENTS OR DIRECTORS OF NATIONAL OLYMPIC ACADEMIES AND OFFICIALS OF NATIONAL OLYMPIC COMMITTEES 12-19 MAY 2010 PROCEEDINGS ANCIENT OLYMPIA 10thDoa003s020.indd 3 4/15/11 2:47:25 PM Commemorative seal of the Session Published by the International Olympic Academy and the International Olympic Committee 2011 International Olympic Academy 52, Dimitrios Vikelas Avenue 152 33 Halandri – Athens GREECE Tel.: +30 210 6878809-13, +30 210 6878888 Fax: +30 210 6878840 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ioa.org.gr Editor: Prof. Konstantinos Georgiadis, IOA Honorary Dean Photographs: IOA Photographic Archives Production: Livani Publishing Organization ISBN: 978-960-14-2350-0 10thDoa003s020.indd 4 4/15/11 2:47:25 PM INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC ACADEMY 10th JOINT INTERNATIONAL SESSION FOR PRESIDENTS OR DIRECTORS OF NATIONAL OLYMPIC ACADEMIES AND OFFICIALS OF NATIONAL OLYMPIC COMMITTEES SPECIAL SUBJECT: NEW CHALLENGES IN THE COLLABORATION AMONG THE IOC, THE IOA, THE NOCs AND THE NOAs ANCIENT OLYMPIA 10thDoa003s020.indd 5 4/15/11 2:47:25 PM 10thDoa003s020.indd 6 4/15/11 2:47:25 PM CONTENTS EPHORIA OF THE INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC ACADEMY (2010) President Isidoros KOUVELOS Vice-President Christos CHATZIATHANASSIOU Members Lambis NIKOLAOU (IOC Member – ex officio member) Spyros KAPRALOS (HΟC President – ex officio member) Emmanuel KATSIADAKIS (HOC Secretary General – ex officio member) Michalis FISSETZIDIS Panagiotis KONDOS Leonidas VAROUXIS Honorary President † Juan Antonio SAMARANCH Honorary Vice-President -

Macau Gaming

Macau Consumer Discretionary 30 July 2019 Macau Gaming Trading on US-China trade tensions Four themes: 1) visa policy support, 2) GBA development, 3) operator promotions with SOEs, and 4) Chinese gamers’ preference for Macau GGR for May (+1.8% YoY) and June (+5.9% YoY) moved into positive Andrew Chung, CFA territory; we expect growth to accelerate in 2H19 (852) 2773 8529 Maintain positive sector view; stock preference: Sands China, Galaxy [email protected] Entertainment, Melco Resorts, MGM China, SJM and Wynn Macau Terry Ng (852) 2773 8530 [email protected] See important disclosures, including any required research certifications, beginning on page 129 Macau Consumer Discretionary 30 July 2019 Macau Gaming Trading on US-China trade tensions Four themes: 1) visa policy support, 2) GBA development, 3) operator promotions with SOEs, and 4) Chinese gamers’ preference for Macau GGR for May (+1.8% YoY) and June (+5.9% YoY) moved into positive Andrew Chung, CFA territory; we expect growth to accelerate in 2H19 (852) 2773 8529 Maintain positive sector view; stock preference: Sands China, Galaxy [email protected] Entertainment, Melco Resorts, MGM China, SJM and Wynn Macau Terry Ng (852) 2773 8530 [email protected] What's new: We see 4 major investment themes emerging for the Macau Key stock calls Gaming Sector amidst ongoing US-China tensions: 1) extended easing of New Prev. domestic travel visa policies, 2) Greater Bay Area (GBA) development in Sands China (1928 HK) Rating Buy Buy improving immigration checkpoint procedures and logistics between Macau Target 50.10 45.60 and GBA cities, 3) continuous collaboration between SOEs and Macau Upside p 27.3% gaming operators, and 4) more Chinese gaming patrons potentially Galaxy Entertainment Group (27 HK) preferring Macau over US gaming destinations. -

Cadernos-De-Politica-Exterior-N-7.Pdf

ISSN 2359-5280 Fundação Alexandre de Gusmão 9 772359 528009 > IPRI Cadernos de Política Exterior ano IV • número 7 • Primeiro semestre 2018 Diplomacia e Discernimento Político: re exão A OCDE em rota de adaptação acerca da natureza da atividade diplomática ao cenário internacional. Perspectivas Benoni Belli para o relacionamento do Brasil com a Organização San Tiago Dantas, a política e a atuação externa do Brasil Rodrigo de Oliveira Godinho Arthur V. C. Meyer Reduzindo o custo de ser estrangeiro: o apoio do Departamento de Política Externa, Desenvolvimento e to de Pesq Promoção Comercial do Itamaraty tu uis Estratégia. A trajetória brasileira i a à internacionalização de empresas st d Sergio Abreu e Lima Florencio brasileiras n e n. 7 I Ideological Repertoires of the Brazilian Foreign Cristiano Franco Berbert Policy toward Africa across three presidential A Inteligência Comercial sob a ótica administrations (1955-2016): from realism to de Larry Kahaner, Michael Porter e south-south solidarity, and back Elaine Marcial José Joaquim Gomes da Costa Filho Félix Baes Baptista de Faria The situation in the Middle East in 2017: a N N: Fundamentos teóricos e práticos da Exterior Política de Cadernos complex equation with numerous variables Diplomacia da Inovação Amine Ait-Chaalal Pedro Ivo Ferraz da Silva D D O Brasil e Índia: 70 anos de relações bilaterais Fukushima, o Japão e o Brasil P CSNU Hudson Caldeira Brant Sandy sete anos depois Goa como plataforma de cooperação Vitor Bahia Diniz P A OCDE entre a Índia e os países lusófonos, -

China's Football Dream

China Soccer Observatory China’s Football Dream nottingham.ac.uk/asiaresearch/projects/cso Edited by: Jonathan Sullivan University of Nottingham Asia Research Institute Contents Domestic Policy. 1. The development of football in China under Xi Jinping. Tien-Chin Tan and Alan Bairner. 2. - Defining characteristics, unintended consequences. Jonathan Sullivan. 3. -Turn. Ping Wu. 4. Emerging challenges for Chinese soccer clubs. Anders Kornum Thomassen. 5. Jonathan Sullivan. 6. Can the Foreign Player Restriction and U-23 Rule improve Chinese football? Shuo Yang and Alan Bairner. 7. The national anthem dilemma - Contextualising political dissent of football fans in Hong Kong. Tobais Zuser. 8. A Backpass to Mao? - Regulating (Post-)Post-Socialist Football in China. Joshua I. Newman, Hanhan Xue and Haozhou Pu. 9. Simon Chadwick. 1 Marketing and Commercial Development. 1. Xi Simon Chadwick. 2. Who is the Chinese soccer consumer and why do Chinese watch soccer? Sascha Schmidt. 3. Corporate Social Responsibility and Chinese Professional Football. Eric C. Schwarz and Dongfeng Liu. 4. Chinese Football - An industry built through present futures, clouds, and garlic? David Cockayne. 5. Benchmarking the Chinese Soccer Market: What makes it so special? Dennis-Julian Gottschlich and Sascha Schmidt. 6. European soccer clubs - How to be successful in the Chinese market. Sascha Schmidt. 7. The Sports Industry - the Next Big Thing in China? Dongfeng Liu. 8. Online streaming media- Bo Li and Olan Scott. 9. Sascha Schmidt. 10. E-sports in China - History, Issues and Challenges. Lu Zhouxiang. 11. - Doing Business in Beijing. Simon Chadwick. 12. Mark Skilton. 2 Internationalisation. 1. c of China and FIFA. Layne Vandenberg. -

How Can We Make the Government to Be Accountable? a Case Study of Macao Special Administrative Region

How can we make the government to be accountable? A Case Study of Macao Special Administrative Region Eilo YU Wing-yat and Ada LEI Hio-leng Department of Government and Public Administration University of Macau Introduction Accountability, which refers to the answerability and responsibility of government officials, is generally considered essential to the achievement of good governance (Moncrieff, 1998). However, the operationalization of accountability is an unresolved issue. In other words, the question of how we make officials truly answerable and responsible to the people is still under debate. Rodan and Hughes (2014) summarize four approaches to understanding the constitution of accountable government: namely, liberal accountability, democratic accountability, moral accountability, and social accountability. Accordingly, accountability is the interplay between government officials and the people through these four approaches, which can help us to understand the extent to which officials are answerable to and sanctioned for their acts. Thereby, accountability may not have a real operational definition because, by nature, it is contextual and shaped through government-mass interactions. This paper aims to understand accountability by examining the case of the Macao Special Administrative Region (MSAR) through an application of Rodan and Hughes’ four approaches to accountability. Its main purpose is to study the political interplay between the Macao people and government for the purpose of making a more accountable government. Its argument is that liberal and democratic accountabilities are not well institutionalized in Macau and that, instead, the MSAR government relies mainly on moral accountability to socialize the public. Leaning toward the liberal approach, the MSAR government has been trying to socialize the moral standards of the Macao masses in order to guide the public’s demand for accountability. -

A Sochi Winter Olympics

Official Newsletter of the Olympic Council of Asia Edition 25 - June 2014 Asia at Sochi 2014 OCA HQ hosts IOC President OCA Games Update OCA Media Committee Contents Inside your 32-page Sporting Asia 3 OCA President’s Message OCA mourns Korean ferry tragedy victims Sporting Asia is the official 4 – 8 NEWS DIGEST newsletter of the Olympic Council of Asia, published 4 Hanoi withdraws as Asian Games host in 2019 quarterly. Kuala Lumpur counts down to IOC Session in 2015 OCA Education Committee Chairman passes away 11 Executive Editor / Director General OCA assists with 2nd COC Youth Camp Husain Al Musallam [email protected] 5 China’s Yu Zaiqing returns as IOC Vice President Children of Asia Games recognise OCA input Art Director / IT Director Top IOC posts for Asian sports leaders Amer Elalami [email protected] 6 ANOC Ex-Co and Olympic Solidarity Commission in Kuwait Director, Int’l & NOC Relations Vinod Tiwari 7 IOC President visits Kuwait, Qatar [email protected] and Saudi Arabia Anti-Doping activities Director, Asian Games Department 22 8 Haider A. Farman [email protected] OS/OCA Regional Forums in Bahrain, Myanmar 9 10 Inside the OCA Editor Jeremy Walker OCA Media Committee [email protected] OCA IT Audit in Thailand Executive Secretary 11 – 22 WELCOME TO SOCHI! Nayaf Sraj [email protected] Twelve pages of Asia at the Winter Olympics starts here Olympic Council of Asia PO Box 6706, Hawalli 23 Overview, Facts and Figures, Photo Gallery 12 – 13 Zip Code 32042 Kuwait 14 Four Asian NOCs join medal rush Telephone: +965 22274277 - 88 15 Final medals -

Policy Address for the Fiscal Year 2003 of the Macao Special Administrative Region (MSAR) of the People’S Republic of China

Policy Address for the Fiscal Year 2003 of the Macao Special Administrative Region (MSAR) of the People’s Republic of China Contents Introduction Part I Summary of the MSAR Government’s Work in 2002 1. Implementing administrative reforms and improving public services 2. Stimulating economic recovery and investment activity 3. Building infrastructure projects and promoting overseas relationships 4. Improving living standards in a safe and peaceful society 5. Summary of achievements Part II Priorities of the MSAR Government in 2003 1. Implementing development plans and boosting business and employment 2. Bolstering regional cooperation and external relations 3. Pursuing administrative reforms and enhancing service quality 4. Striving for educational excellence and consolidating humanistic traditions Part III Adopting a Holistic Approach to Macao’s Development Conclusion Policy Address for the Fiscal Year 2003 of the Macao Special Administrative Region (MSAR) of the People’s Republic of China Delivered by the Chief Executive, Edmund Hau Wah HO 20 November 2002 Madam President, members of the Legislative Assembly, Today, I am pleased to attend the plenary meeting of the Legislative Assembly of the Macao Special Administrative Region. In accordance with the terms stipulated in the Basic Law and on behalf of the MSAR Government, I now present the policy report for the fiscal year 2003 for your evaluation and discussion. Introduction For nearly three years, the Macao Special Administrative Region (MSAR) has been guided by the principles of “One country, two systems”, “Macao people governing Macao” and “A high degree of autonomy”. In the process of adapting to changing times, we are continuing to implement administrative reforms, to strengthen and unify Macao and to make steady progress in a stable social and economic environment. -

Universidade Federal Da Bahia Instituto De Geociências Departamento De Geografia Marcelo Goulart Unilab: Instrumento De Integra

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DA BAHIA INSTITUTO DE GEOCIÊNCIAS DEPARTAMENTO DE GEOGRAFIA MARCELO GOULART UNILAB: INSTRUMENTO DE INTEGRAÇÃO DA COMUNIDADE DOS PAÍSES DE LÍNGUA PORTUGUESA (CPLP) SALVADOR 2015 MARCELO GOULART UNILAB: INSTRUMENTO DE INTEGRAÇÃO DA COMUNIDADE DOS PAÍSES DE LÍNGUA PORTUGUESA (CPLP) Monografia apresentada como pré-requisito de conclusão do curso de Bacharelado em Geografia, da Universidade Federal da Bahia. Orientador: Alcides dos Santos Caldas SALVADOR 2015 Ficha catalográfica elaborada pela Biblioteca do Instituto de Geociências - UFBA S237u Santos, Marcelo Goulart UNILAB: Instrumento de Integração da Comunidade dos Países de Língua Portuguesa (CPLP) / Marcelo Goulart Santos.- Salvador, 2015. 163 f. : il. Color. Orientador: Prof. Alcides dos Santos Caldas Monografia (Conclusão de Curso) – Universidade Federal da Bahia. Instituto de Geociências, 2015. 1. Universidade da Integração Internacional da Lusofonia Afro- brasileira. 2. Intercâmbio cultural e científico - Países de Língua Portuguesa. 3. Geopolítica. 4. Universidades e faculdades - Cooperação internacional. I. Caldas, Alcides dos Santos. II. Universidade Federal da Bahia. III. Título. CDU: 378.4 MARCELO GOULART UNILAB: INSTRUMENTO DE INTEGRAÇÃO DA COMUNIDADE DOS PAÍSES DE LÍNGUA PORTUGUESA (CPLP) Monografia apresentada como pré-requisito de conclusão do curso de Bacharelado em Geografia, da Universidade Federal da Bahia. Orientador: Alcides dos Santos Caldas Aprovado em 25/11/2015. Banca Examinadora: Prof. Dr. Alcides dos Santos Caldas (Orientador) Universidade Federal da Bahia Profa. Dra. Caterina Alessandra Rea Universidade da Integração Internacional da Lusofonia Afro-brasileira Profa. Dra. Maria Auxiliadora da Silva Universidade Federal da Bahia SALVADOR 2015 “É preciso sonhar, mas com a condição de crer em nosso sonho, de observar com atenção a vida real, de confrontar a observação com nosso sonho, de realizar escrupulosamente nossas fantasias. -

Entidade País/Sede Nome Cargo/Função Email Telefone Ao Cuidado De Morada

Entidade País/Sede Nome Cargo/Função Email Telefone Ao cuidado de Morada Avenida Presidente Wilson 203, Castelo Academia Brasileira de Letras Brasil Geraldo Holanda Cavalcanti Embaixador [email protected] 0055 21 3974 2500 CEP 20030-021 Rio de Janeiro - Brasil www.academiagalega.org Cell: 00351 968358747 Maria Dovigo, Delegada da AGLP em [email protected] Academia Galega da Língua Portuguesa Espanha Professor Rudesindo Soutelo Presidente Tel.: 00351 218098146 Lisboa [email protected] ([email protected]) R. José do Patrocínio, 49 Marvila AMI-Assistência Médica Internacional Portugal Prof. Dr. Fernando Nobre Presidente [email protected] 21 836 2100 1959-003 Lisboa Cabo Rua Duque de Palmela, nº2 8º Associação Caboverdeana de Lisboa Dr. Filipe Nascimento Presidente [email protected] 21 359 3367 Verde/Portugal 1250-098 Lisboa Av. Nossa Senhora de Copacabana, nº 794 – Associação Cultural TALU Produções e Marketing Barsil Dra. Tânia Maria Rocha Pires Presidente [email protected] 55 21 2579-5778 sala 405 Copacabana – R.J Avenida Impeatriz Leopoldina, 1150 Associação Cultural Videobrasil Brasil Dra. Solange o. Farkas Diretora [email protected] 0055 11 36450516 Vila Leopoldina São Paulo - SP 05305-002 Isabel Cancela de Abreu Rua Braamcamp 84, 3º D Associação Lusófona de Energias Renováveis (ALER) Portugal Dra. Miquelina Menezes Presidente [email protected] 21 137 9288 (Diretora Executiva) 1250-052 Lisboa Cais da Rocha Conde d’Óbidos Dr. José Luís Azevedo Cacho Edifício da Gare Marítima – 1º Piso - A Associação de Portos de Língua Oficial Portuguesa (APLOP) Portugal Dr. Casemiro Tércio Carvalho Presidente [email protected] 21 396 20 35 ([email protected]) 1350 – 352 LISBOA Dr. -

Series I No. 8.Pmd

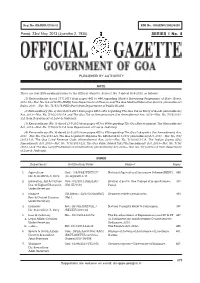

Reg. No. GR/RNP/GOA/32 RNI No. GOAENG/2002/6410 Panaji, 23rd May, 2013 (Jyaistha 2, 1935) SERIES I No. 8 PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY NOTE There are four Extraordinary issues to the Official Gazette, Series I No. 7 dated 16-5-2013, as follows:— (1) Extraordinary dated 17-5-2013 from pages 441 to 444 regarding Market Borrowing Programme of State Govts. 2013-14—Not. No. 5-2-2012-Fin (DMU) from Department of Finance and The Goa Medical Education Service (Amendment) Rules, 2013—Not. No. 71/51/79-PHD (Part) from Department of Public Health. (2) Extraordinary (No. 2) dated 20-5-2013 from pages 445 to 452 regarding The Goa Tax on Entry of Goods (Amendment) Act, 2013—Not. No. 7/16/2013-LA and The Goa Tax on Infrastructure (1st Amendment) Act, 2013—Not. No. 7/18/2013- -LA from Department of Law & Judiciary. (3) Extraordinary (No. 3) dated 21-5-2013 from pages 453 to 454 regarding The Goa Entertainment Tax (Amendment) Act, 2013—Not. No. 7/15/2013-LA from Department of Law & Judiciary. (4) Extraordinary (No. 4) dated 22-5-2013 from pages 455 to 478 regarding The Goa Lokayukta (1st Amendment) Act, 2013—Not. No. 7/2/2013-LA, The Goa Legislative Diploma No. 645 dated 30-3-1933 (Amendment) Act, 2013—Not. No. 7/8/ /2013-LA, The Goa Land Revenue Code (Amendment) Act, 2013—Not. No. 7/10/2013-LA, The Indian Stamp (Goa Amendment) Act, 2013—Not. No. 7/13/2013-LA, The Goa Value Added Tax (7th Amendment) Act, 2013—Not. -

Annual Report of the National Olympic Committee for the Year 2017

Report of the Secretary General 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 It is with great pleasure and pride I take this opportunity to present the Annual Report of the National Olympic Committee for the year 2017. During the given period, in spite the ups and downs within; the NOC SL as an organisation gathered strength and momentum to shape itself towards future stability. 2. STRUCTURE & ORGANISATION 2.1 Expansion Membership was granted to the following four Associations. 1) Sri Lanka Rugby Football Union 2) Sri Lanka Karate-do Federation 3) National Roller Skating Association 4) Sri Lanka Amateur Baseball Association 5) Modern Pentathlon Federation of Sri Lanka Thereby the affiliation of membership was increased to 31. 2.2 Meetings Since the office was running by Office Bearers, one office bearers meeting was held 6th November 2017 prior to the General Assembly which was held on 9th November 2017. Also, there were 6 Management Committee meetings conducted during the year 2017. 2.3 Changes of the Office Bearers The total number of Office Bearers were remained 11 due to the life time suspension imposed on Mr. Manilal Fernando by the FIFA. 2.4 Sub-Committees The following Committees were formalized and functioned during the year 2017. Education Committee – Mr. Preethi Perera, Chairman Mr. Nishanthe Piyasena, Member (Assistant Secretary of NOC Sri Lanka) Mr. Gamini Jayasinghe, Member (Treasurer of NOC Sri Lanka) Finance Committee – Mr. Rohan Fernando, Chairman Procurement Committee – Mr. Joseph Kenny, Chairman (Vice President of NOC Sri Lanka) Mr. Deva Henry, Member (Vice President of NOC Sri Lanka) Mr. Chandana Perera, Member (Assistant Treasurer of NOC Sri Lanka) Nominations Committee – Mr.