Working with the Winds of Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Voice of Senior Citizens, Dec. Issue

AGEING IN NEPALI PRESS (Nov. 1-30, 2015) ADVOCACY Participated in the Campaign Ageing Nepal Kathmandu, November, 2015 Ageing Nepal participated in the Global Climate March Campaign to mark the COP21 of 29th November. On 29th November the leaders and head of the state of more than 190 countries came together for climate talks in Paris. The world took part in the Global Climate March, calling on leaders to use the opportunity of the UN climate talks in Paris to accelerate progress in the fight against climate change. Ageing Nepal organized various supportive campaign activities like: TV Talk show, Radio Talk show, article publication on the importance of COP21, workshop, petition handover to the government authorities and so on before 29th Nov. Similarly in the major event of the 29th Nov. various activities were conducted in different districts. The following table presents campaign activities and related districts. S.N. Activities Districts 1. Rallies Elephant Horse Cart Chitwan Rickshaw Older Person Jhapa Student Kathmandu 2. Cultural Dance Syangja 3. Paragliding with Banners Kaski 4. Joined a Rally Lalitpur Each campaign activities was conducted under the main banner of COP21 and campaign materials like non- plastic bags, pamphlets, stickers were distributed to participants of the campaign. Ph: +977-01-4485827 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ageingnepal.org 1 Major Highlights of the Campaign Total media mobilization: Print media: 1; Television programme: 2; Radio programme: 1 Total people reached with Media: 9,000,000 Total -

The 46Th Annual

the 46th Annual 2018 TO BENEFIT NANTUCKET COMMUNITY SAILING PROUD TO SPONSOR MURRAY’S TOGGERY SHOP 62 MAIN STREET | 800-368-3134 2 STRAIGHT WHARF | 508-325-9600 1-800-892-4982 2018 elcome to the 15th Nantucket Race Week and the 46th Opera House Cup Regatta brought to you by Nantucket WCommunity Sailing, the Nantucket Yacht Club and the Great Harbor Yacht Club. We are happy to have you with us for an unparalleled week of competitive sailing for all ages and abilities, complemented by a full schedule of awards ceremonies and social events. We look forward to sharing the beauty of Nantucket and her waters with you. Thank you for coming! This program celebrates the winners and participants from last year’s Nantucket Race Week and the Opera House Cup Regatta and gives you everything you need to know about this year’s racing and social events. We are excited to welcome all sailors in the Nantucket community to join us for our inaugural Harbor Rendezvous on Sunday, August 12th. We are also pleased to welcome all our competitors, including young Opti and 420 racers; lasers, Hobies and kite boarders; the local one design fleets; the IOD Celebrity Invitational guest tacticians and amateur teams; and the big boat regatta competitors ranging from Alerions and Wianno Seniors to schooners and majestic classic yachts. Don’t forget that you can go aboard and admire some of these beautiful classics up close, when they will be on display to the public for the 5th Classic Yacht Exhibition on Saturday, August 18th. -

CEDAW Shadow Report Writing Process Consultation Meeting on CEDAW Shadow • Take Away on CEDAW Shadow Report Report Writing Process

FWLD’S QUARTERLY ONLINE BulletinVol. 8 Year 3 Jan-Mar, 2019 CEDAW SHADOW REPORT WRITING Working for non-discrimination PROCESS and equality Formation of Shadow Report Preparation Inside Committee (SRPC) • CEDAW Shadow Report Writing Process Consultation Meeting on CEDAW Shadow • Take away on CEDAW Shadow Report Report Writing Process • Take away on Citizenship/Legal Aid Provincial Consultation on draft of CEDAW • Take away on Inclusive Transitional Justice Shadow Report • Take away on Reproductive Health Rights • Take away on Violence against Women Discussion on List of Issues (LOI) • Take away on Status of Implementation of Constitution and International Instruments National Consultation of the CEDAW Shadow • Media Coverage on the different issues initiated by FWLD Report Finalization of CEDAW Shadow Report Participated in the Reveiw of 6th Periodic Report of Nepal on CEDAW Concluding Observations on Sixth Periodic Report of Nepal on CEDAW Take away on CEDAW SHADOW REPORT A productive two days consultative meeting on CEDAW obligations on 2nd and 3rd October 2018. Submission of CEDAW Press meet on CEDAW Shadow Report CEDAW Shadow Report Preparation Committee coordinated by FWLD has submitted the CEDAW Shadow Report and the A press meet was organized on 11th Oct. 2018 to report has been inform media about reporting process of Shadow uploaded in Report on Sixth Periodic Report of Nepal on CEDAW. The timeline of review of the report and its OHCHR’s website on outcome was also discussed. October 1st 2018. NGO Briefs and Informal Country meeting on the Lunch Meeting role of civil society in the 71st Session of CEDAW A country meeting was organized to discuss about the role of civil society in the 71st Session of CEDAW on 11th Oct, 2018. -

2010 Year Book

2010 YEAR BOOK www.massbaysailing.org $5.00 HILL & LOWDEN, INC. YACHT SALES & BROKERAGE J boat dealer for Massachusetts and southern new hampshire Hill & Lowden, Inc. offers the full range of new J Boat performance sailing yachts. We also have numerous pre-owned brokerage listings, including quality cruising sailboats, racing sailboats, and a variety of powerboats ranging from runabouts to luxury cabin cruisers. Whether you are a sailor or power boater, we will help you find the boat of your dreams and/or expedite the sale of your current vessel. We look forward to working with you. HILL & LOWDEN, INC. IS CONTINUOUSLY SEEKING PRE-OWNED YACHT LISTINGS. GIVE US A CALL SO WE CAN DISCUSS THE SALE OF YOUR BOAT www.Hilllowden.com 6 Cliff Street, Marblehead, MA 01945 Phone: 781-631-3313 Fax: 781-631-3533 Table of Contents ______________________________________________________________________ INFORMATION Letter to Skippers ……………………………………………………. 1 2009 Offshore Racing Schedule ……………………………………………………. 2 2009 Officers and Executive Committee …………… ……………............... 3 2009 Mass Bay Sailing Delegates …………………………………………………. 4 Event Sponsoring Organizations ………………………………………................... 5 2009 Season Championship ………………………………………………………. 6 2009 Pursuit race Championship ……………………………………………………. 7 Salem Bay PHRF Grand Slam Series …………………………………………….. 8 PHRF Marblehead Qualifiers ……………………………………………………….. 9 2009 J105 Mass Bay Championship Series ………………………………………… 10 PHRF EVENTS Constitution YC Wednesday Evening Races ……………………………………….. 11 BYC Wednesday Evening -

Guide to 275 SIVA STHALAMS Glorified by Thevaram Hymns (Pathigams) of Nayanmars

Guide to 275 SIVA STHALAMS Glorified by Thevaram Hymns (Pathigams) of Nayanmars -****- by Tamarapu Sampath Kumaran About the Author: Mr T Sampath Kumaran is a freelance writer. He regularly contributes articles on Management, Business, Ancient Temples and Temple Architecture to many leading Dailies and Magazines. His articles for the young is very popular in “The Young World section” of THE HINDU. He was associated in the production of two Documentary films on Nava Tirupathi Temples, and Tirukkurungudi Temple in Tamilnadu. His book on “The Path of Ramanuja”, and “The Guide to 108 Divya Desams” in book form on the CD, has been well received in the religious circle. Preface: Tirth Yatras or pilgrimages have been an integral part of Hinduism. Pilgrimages are considered quite important by the ritualistic followers of Sanathana dharma. There are a few centers of sacredness, which are held at high esteem by the ardent devotees who dream to travel and worship God in these holy places. All these holy sites have some mythological significance attached to them. When people go to a temple, they say they go for Darsan – of the image of the presiding deity. The pinnacle act of Hindu worship is to stand in the presence of the deity and to look upon the image so as to see and be seen by the deity and to gain the blessings. There are thousands of Siva sthalams- pilgrimage sites - renowned for their divine images. And it is for the Darsan of these divine images as well the pilgrimage places themselves - which are believed to be the natural places where Gods have dwelled - the pilgrimage is made. -

UP Flood Situation Report

Flood Situation Report Date: 3rd & 4th July 2018 Developed by: PoorvanchalGraminVikasSansthan (PGVS) Flood Situation of Uttarakhand: Flash floods triggered by heavy rain and washed away 16 roads and 10 bridges in Uttarakhand’s Pithoragarh district, currently cutting off access to 41 villages with some 18,000 residents. Flood situation in upstream area, Nepal in Sharda River (Mahakali): Due to effects of this, water in Sharda River and also rain fall in upstream areas of Mahakali (Sharda) River, water level arisen in Parigaon DHM station, Nepal with nearest warning level is 5.34 on 2nd July 2018. Currently the water level of the Mahakali (Sharda) River is 4.452 Miter and trend is falling in Parigaon DHM station, Nepal. Details of the water level from 27 June to till date is given below (Pic 1) (Picture 1) Daily water level of Sharda River from 27 June to 3 July 2018 (Source: Website DHM, Nepal) Flood situation in downstream areas of Uttar Pradesh, India: As per flood bulletin ((3rd July 2108)) of irrigation department, the Sharda River is flowing 0.230 Miter above danger level (153.620 Miter) in Paliyakala, Lakhimpur and currently trend of this river is rising. It’s flowing below danger level 1.420 Miter (135.490 Miter) in Shardanagar. The rainfall 171.4 MM in Banbasa, 118 MM in Paliyakalan ad 100 MM in Shardanagar were also contributed in worsening the situation in last three days. As per Dainik Jagran Newspaper (Page no.3), the Banbasa Barrage had discharged 117000 Qu. water. It will affect Mahsi Areas by today evening. -

Air Pollution Monitoring in Urban Areas Due to Heavy Transportation and Industries: a Case Study of Rawalpindi and Islamabad

MUJTABA HASSAN et al., J.Chem.Soc.Pak., Vol. 35, No. 6, 2013 1623 Air pollution Monitoring in Urban Areas due to Heavy Transportation and Industries: a Case Study of Rawalpindi and Islamabad 1 Mujtaba Hassan, 2 Amir Haider Malik, 3 Amir Waseem*, and 4 Muhammad Abbas 1Institute of Space Technology, Department of Space Science, Islamabad, Pakistan. 2Department of Environmental Sciences, COMSATS Institute of Information Technology, Abbottabad, Pakistan. 3Department of Chemistry, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan. 4Department of Environment Science and Engineering, National University of Science and Technology, Islamabad Pakistan. [email protected]* (Received on 7th January 2013, accepted in revised form 6th May 2013) Summary: The present study deals with the air pollution caused by Industry and transportation in urban areas of Pakistan. Rawalpindi and Islamabad, the twin cities of Pakistan were considered for this purpose. The concentrations of major air pollutants were taken from different location according their standard time period using Air Quality Monitoring Station. Five major air pollutants were considered i.e., NO2, SO2, CO, O3 and PM2.5. The average mean values for all pollutants were taken on monthly and four monthly bases. The concentrations of NO2 and PM2.5 were exceeding the permissible limits as define by Environmental Protection Agency of Pakistan. Other pollutants concentrations were within the standard limits. Geographic Information System was used as a tool for the representation and analysis of Environmental Impacts of air pollution. Passquill and Smith dispersion model was used to calculate the buffer zones. Some mitigation measures were also recommended to assess the environmental and health Impacts because of PM2.5 and NO2. -

Pakistan: Lai Nullah Basin Flood Problem Islamabad – Rawalpindi Cities

WORLD METEOROLOGICAL ORGANIZATION THE ASSOCIATED PROGRAMME ON FLOOD MANAGEMENT INTEGRATED FLOOD MANAGEMENT CASE STUDY1 PAKISTAN: LAI NULLAH BASIN FLOOD PROBLEM ISLAMABAD – RAWALPINDI CITIES January 2004 Edited by TECHNICAL SUPPORT UNIT Note: Opinions expressed in the case study are those of author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the WMO/GWP Associated Programme on Flood Management (APFM). Designations employed and presentations of material in the case study do not imply the expression of any opinion whatever on the part of the Technical Support Unit (TSU), APFM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. LIST OF ACRONYMS ADB Asian Development Bank ADPC Asian Disaster Preparedness Centre ADRC Asian Disaster Reduction Centre CDA Capital Development Authority Cfs Cubic Feet Per Second DCOs District Coordination Officers DTM Digital Terrain Model ECNEC Executive Committee of National Economic Council ERC Emergency Relief Cell FFC Federal Flood Commission FFD Flood Forecasting Division FFS Flood Forecasting System GPS Global Positioning System ICID International Commission on Irrigation & Drainage ICIMOD International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development ICOLD International Commission on Large Dams IDB Islamic Development Bank IFM Integrated Flood Management IWRM Integrated Water Resources Management JBIC Japan Bank for International Cooperation JICA Japan International Cooperation Agency LLA Land Acquisition Act MAF -

Short Communications Assessment Of

Short Communications Pakistan J. Zool., vol. 45(2), pp. 555-558, 2013. diarrohoea, endocarditis, and bacterimia (Nannini et al., 2005). Enterococci are facultative anaerobic, Assessment of Antibacterial Activity Gram positive cocci that live as normal flora in the of Momordica charantia Extracts and gastrointestinal tract of humans and animals (Kiem et al., 2003). Enterococcus species are indicators of Antibiotics against Fecal animal and human fecal contamination in water and Contaminated Water Associated various food products (Moneoang and Enterococcus spp. Bezuidenhout, 2009; Valenzuela et al., 2008). More than twenty species of Enterococci Saiqa Andleeb1*, Tahseen Ghous2, Nazia Riaz1, have been classified. Enterococcus faecium and Nosheen Shahzad2, Summya Ghous1 and Uzma Enterococcus faecalis are the mostly indentified Azeem Awan1 species in humans, animals, food products and water 1Biotechnology laboratory, Department of Zoology, (Facklam, 2002). Fisher and Philips (2009) Azad Jammu and Kashmir University, demonstrated that these pathogens would cause Muzaffarabad 13100, Pakistan disease if the hosts immune system is suppressed. 2Biochemistry Laboratory, Department of Hydrogen peroxide derived from E. faecium was Chemistry, Azad Jammu and Kashmir University, shown to damage luminal cells in the colon of rats Muzaffarabad 13100, Pakistan (Huycke et al., 2002). Infectious pathogens have been reduced using various medicinal plants such as Abstract.- Antibacterial activity of Momordica charantia due to their potential extracts of Momordica charantia and several antidiabetic, antihelmintic, antmicrobial, anti- antibiotics were studied against Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium isolated cancerigenos and antioxidant activities (Costa et al., from water receiving fertilizers of animal origin 2011). In the present study Enterococcus pathogens by filter disc diffusion method. E. -

List of Publications WIN 1 Nov, 06

WINROCK INTERNATIONAL POLICY ANALYSIS IN AGRICULTURE AND RELATED RESOURCE MANAGEMENT LIST OF PUBLICATIONS (Listed by Series Name/Author's Name/Title/Year) A. NATURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PAPER SERIES (until 1989): Office Copy 1. Bachchu Prasad Koirala, "Economics of Land Reform in Nepal: Case Study of Dhanusha District", July 1987. 2. Om Prasad Gurung, "Interrelationships among Pasture, Animal Husbandry and Agriculture: Case Study of Tara", July 1987. 3. C.M. Pokharel, "Community Fish Farming in Nepal Tarai: Case Study of Bhawanipur and Hanuman Nagar", July 1987. 4. Mahesh Prasad Pant, "Community Participation in Irrigation Management: Case Study of Solma Irrigation Project in East Nepal", August 1987. 5. Bandana Pradhan, "Animal Nutrition and Pasture Fodder Management: The Case of Mahespur", November 1987. 6. Prakash Dev Pant, "Socioeconomic Consequences of Land Ownership Polarization in Nepal: Case Study of Nemuwatole Village", November 1987. 7. Badri Jha, "Evaluation of Land Tenure System: Case Study of Jaisithok Village ", November 1987. 8. Upendra Gautam, "Institution Building and Rural Development in Nepal: Gadkhar Water Users' Committee", November 1987. 9. Parashar B. Malla, "Group Fish Farming Under the Small Farmers Development Project at Chandranagar", December 1987. 10. S.P. Shrestha, "Community-managed Irrigation Systems: Case Study of Arughat- Vishal Nagar Pipe Irrigation Project", December 1987. 11. Bimal Prasad Dhungel, "Sociocultural and Legal Arrangements for Grazing on Public Land: Case Study of Bahadurganj", December 1987. 12. Murari M. Aryal, "Participatory Irrigation Management: Case Study of Bhadrutar and Hakuwa Canals",December 1987. 1 13. Ramesh Bista, "Cross-Sectional Variations and Temporal Changes in Land Area under Tenancy and their Implications for Agricultural Productivity", January 1989. -

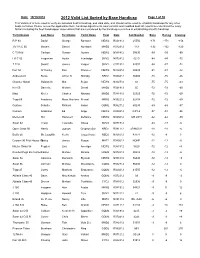

2012 Valid List Sorted by Base Handicap

Date: 10/19/2012 2012 Valid List Sorted by Base Handicap Page 1 of 30 This Valid List is to be used to verify an individual boat's handicap, and valid date, and should not be used to establish handicaps for any other boats not listed. Please review the appilication form, handicap adjustments, boat variants and modified boat list reports to understand the many factors including the fleet handicapper observations that are considered by the handicap committee in establishing a boat's handicap Yacht Design Last Name First Name Yacht Name Fleet Date Sail Number Base Racing Cruising R P 90 David George Rambler NEW2 R021912 25556 -171 -171 -156 J/V I R C 66 Meyers Daniel Numbers MHD2 R012912 119 -132 -132 -120 C T M 66 Carlson Gustav Aurora NEW2 N081412 50095 -99 -99 -90 I R C 52 Fragomen Austin Interlodge SMV2 N072412 5210 -84 -84 -72 T P 52 Swartz James Vesper SMV2 C071912 52007 -84 -87 -72 Farr 50 O' Hanley Ron Privateer NEW2 N072412 50009 -81 -81 -72 Andrews 68 Burke Arthur D Shindig NBD2 R060412 55655 -75 -75 -66 Chantier Naval Goldsmith Mat Sejaa NEW2 N042712 03 -75 -75 -63 Ker 55 Damelio Michael Denali MHD2 R031912 55 -72 -72 -60 Maxi Kiefer Charles Nirvana MHD2 R041812 32323 -72 -72 -60 Tripp 65 Academy Mass Maritime Prevail MRN2 N032212 62408 -72 -72 -60 Custom Schotte Richard Isobel GOM2 R062712 60295 -69 -69 -57 Custom Anderson Ed Angel NEW2 R020312 CAY-2 -57 -51 -36 Merlen 49 Hill Hammett Defiance NEW2 N020812 IVB 4915 -42 -42 -30 Swan 62 Tharp Twanette Glisse SMV2 N071912 -24 -18 -6 Open Class 50 Harris Joseph Gryphon Soloz NBD2 -

Nagapattinam District

CENSUS OF INDIA 2011 TOTAL POPULATION AND POPULATION OF SCHEDULED CASTES AND SCHEDULED TRIBES FOR VILLAGE PANCHAYATS AND PANCHAYAT UNIONS NAGAPATTINAM DISTRICT DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS TAMILNADU ABSTRACT NAGAPATTINAM DISTRICT No. of Total Total Sl. No. Panchayat Union Total Male Total SC SC Male SC Female Total ST ST Male ST Female Village Population Female 1 Nagapattinam 29 83,113 41,272 41,841 31,161 15,476 15,685 261 130 131 2 Keelaiyur 27 76,077 37,704 38,373 28,004 13,813 14,191 18 7 11 3 Kilvelur 38 70,661 34,910 35,751 38,993 19,341 19,652 269 127 142 4 Thirumarugal 39 87,521 43,397 44,124 37,290 18,460 18,830 252 124 128 5 Thalainayar 24 61,180 30,399 30,781 22,680 11,233 11,447 21 12 9 6 Vedaranyam 36 1,40,948 70,357 70,591 30,166 14,896 15,270 18 9 9 7 Mayiladuthurai 54 1,64,985 81,857 83,128 67,615 33,851 33,764 440 214 226 8 Kuthalam 51 1,32,721 65,169 67,552 44,834 22,324 22,510 65 32 33 9 Sembanarkoil 57 1,77,443 87,357 90,086 58,980 29,022 29,958 49 26 23 10 Sirkali 37 1,28,768 63,868 64,900 48,999 24,509 24,490 304 147 157 11 Kollidam 42 1,37,871 67,804 70,067 52,154 25,800 26,354 517 264 253 Grand Total 434 12,61,288 6,24,094 6,37,194 4,60,876 2,28,725 2,32,151 2,214 1,092 1,122 NAGAPATTINAM PANCHAYAT UNION Sl.