Ars Musicologica

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

George Enescu, Posthumously Reviewed

George Enescu, Posthumously Reviewed Va lentina SANDU-DEDIU National University of Music Bucharest Strada Știrbei Vodă 33, București, Ro-010102 Romania New Europe College Bucharest Strada Plantelor 21, București, Ro-023971 Romania E-mail: [email protected] (Received: November 2017; accepted: January 2018) Abstract: This essay tackles some aspects related to the attitude of the Romanian officials after George Enescu left his country definitively (in 1946). For example, re- cent research through the archives of the former secret police shows that Enescu was under the close supervision of Securitate during his last years in Paris. Enescu did not generate a compositional school during his lifetime, like for instance Arnold Schoen- berg did. His contemporaries admired him, but each followed their own path and had to adapt differently to an inter-war, then to a post-war, Communist Romania. I will therefore sketch the approach of younger composers in relation to Enescu (after 1955): some of them attempted to complete unfinished manuscripts; others were in fluenced by ideas of Enescu’s music. The posthumous reception of Enescu means also an in- tense debate in the Romanian milieu about his “national” and “universal” output. Keywords: Securitate, socialist realism in Romania, “national” and “universal,” het- erophony, performance practice It is a well-known fact that George Enescu did not create a school of composition during his lifetime, neither in the sense of direct professor–student transmission of information, as was the case in Vienna with Arnold Schoenberg, nor in the wider sense of a community of ideas or aesthetic principles. His contemporaries admired him, but they each had their own, well-established stylistic paths; in the Stalinist post-war period, some of them subordinated their work to the ideological requirements of socialist realism and it was generally discouraged to discern the subtle, but substantial renewals of Enescu’s musical language. -

Constante Şi Deschideri În Cvartetele De Coarde Ale Lui Wilhelm Georg Berger (I)

MUZICA nr.1/2010 CREAŢII Monica CENGHER Constante şi deschideri în cvartetele de coarde ale lui Wilhelm Georg Berger (I) Interesul lui W.G.Berger pentru genurile instrumentale verificate de proba îndelungată a istoriei, primordiale fiind cvartetul de coarde şi simfonia alături de concertul instrumental şi sonată, s-a concretizat într-o vastă operă de autor, elaborată în spiritul unui virtual dar ingenios dialog cu valorile supreme ale culturii. Sintagma goetheană “dacă vrei să păşeşti în infinit, parcurge finitul din toate direcţiile” este emblematică demersului său artistic. Vocaţia renascentistă de a iscodi concreteţea artei muzicale din mai multe ipostaze (istorice, estetice, matematice, componistice şi nu în ultimul rând interpretative), a fost dublată de însuşirile unei personalităţi profunde, înzestrată cu o fină inteligenţă, generozitate şi fire contemplativă cu nuanţe de blândeţe. “Fenomenul W. Berger – căci a fost un fenomen cu totul neobişnuit – nu s-a produs în locuri obscure sau ascunse, ci în plină lumină”1- releva pe un ton admirativ Pascal Bentoiu. Această forţă iradiantă însoţită de bucuria revelaţiei pe care i-a oferit-o cunoaşterea, l-au călăuzit întreaga viaţă, conturându-i opera de autor pe dimensiuni monumentale, masive şi de o anvergură nemaiîntâlnită la noi. Abundenţa cu care dădea la iveală creaţiile muzicale şi lucrările muzicologice reprezintă amplitudinea aspiraţiilor sale de largă cuprindere, în care erudiţia naşte imaginaţie şi detaliul se generalizează în concepte abstracte. Există o cadenţă în evoluţia lui W.G.Berger. Pe de o parte urmăreşte împlinirea unor ţeluri pe planul gândirii despre muzică, pornind de la analiza resorturilor intime ale fenomenului muzical, conturând liniile de forţă ale curentelor şi mentalităţilor artistice; pe de altă parte, se defineşte printr-o consistentă gândire componistică cu deschideri atât către tradiţii cât şi spre înnoiri. -

AM-2015-12.Pdf

Serie nouã ACTUALITATEA decembrie12 2015 (CLXXIII) 48 pagini MUZICAL~ ISSN MUZICAL~ 1220-742X REVISTĂ LUNARĂ A UNIUNII COMPOZITORILOR ŞI MUZICOLOGILOR DIN ROMÂNIA D i n s u m a r: Uniunea Compozitorilor şi Muzicologilor la 95 de ani Festivalul Internaţional MERIDIAN Festivalul INTRADA, Timişoara Danube Jazz & Blues Festival Rock îndoliat În imagine: Constantin Brăiloiu, Alfred Alessandrescu, Lansare carte Maria Dragomiroiu George Enescu, Ion Nonna Otescu, Mihail Jora Recunoaştere Preşedintele României Klaus Johannis a înmânat, în cadrul ceremoniei din data de 05.11.2015, UNIUNII COMPOZITORILOR ŞI MUZICOLOGILOR DIN ROMÂNIA (UCMR), cu prilejul aniversării a 95 de ani de la înfiinţarea Societăţii Compozitorilor Români (precursoarea UCMR) şi a aniversării a 20 de ani de la constituirea Alianţei Naţionale a Uniunilor de Creaţie (ANUC), Ordinul „MERITUL CULTURAL” în grad de „OFIŢER”. În argumentarea aferentă distincţiei se menţionează că aceasta se conferă în semn de înaltă apreciere pentru implicarea directă şi constantă în organizarea şi promovarea manifestărilor muzicale, pentru meritele deosebite avute la susţinerea patrimoniului clasic autohton, a creaţiei muzicale contemporane, contribuind astfel la afirmarea internaţională a compozitorilor şi muzicologilor români. DIN SUMAR UCMR la 95 de ani................................1-10 Interviu cu dl. Ulpiu Vlad....................11-12 Festivalul internaţional MERIDIAN.....13-27 Conferinţa OPERA EUROPA.................27-28 Tatiana Lisnic la ONB..........................28-29 Concerte sub... lupă.................................31 Corespondenţă de la Oldenburg...........32-33 Festivalul INTRADA.............................34-35 “In Memoriam #colectiv”....................36-37 “Danube Jazz & Blues Festival”...........38-39 Rock îndoliat......................................42-43 Lansare carte Maria Dragomiroiu........44-45 Discuri................................................46-47 Muzica pe micul ecran.............................48 ACTUALITATEA MUZICALĂ Nr. 12 Decembrie 2015 1 UCMR 95 timp de răzBOI. -

THE UNKNOWN ENESCU Volume One: Music for Violin

THE UNKNOWN ENESCU Volume One: Music for Violin 1 Aubade (1899) 3:46 17 Nocturne ‘Villa d’Avrayen’ (1931–36)* 6:11 Pastorale, Menuet triste et Nocturne (1900; arr. Lupu)** 13:38 18 Hora Unirei (1917) 1:40 2 Pastorale 3:30 3 Menuet triste 4:29 Aria and Scherzino 4 Nocturne 5:39 (c. 1898–1908; arr. Lupu)** 5:12 19 Aria 2:17 5 Sarabande (c. 1915–20)* 4:43 20 Scherzino 2:55 6 Sérénade lointaine (1903) 4:49 TT 79:40 7 Andantino malinconico (1951) 2:15 Sherban Lupu, violin – , Prelude and Gavotte (1898)* 10:21 [ 20 conductor –, – 8 Prelude 4:32 Masumi Per Rostad, viola 9 Gavotte 5:49 Marin Cazacu, cello , Airs dans le genre roumain (1926)* 7:12 Dmitry Kouzov, cello , , 10 I. Moderato (molto rubato) 2:06 Ian Hobson, piano , , , , , 11 II. Allegro giusto 1:34 Ilinca Dumitrescu, piano , 12 III. Andante 2:00 Samir Golescu, piano , 13 IV. Andante giocoso 1:32 Enescu Ensemble of the University of Illinois –, – 20 14 Légende (1891) 4:21 , , , , , , DDD 15 Sérénade en sourdine (c. 1915–20) 4:21 –, –, –, , – 20 ADD 16 Fantaisie concertante *FIRST RECORDING (1932; arr. Lupu)* 11:04 **FIRST RECORDING IN THIS VERSION 16 TOCC 0047 Enescu Vol 1.indd 1 14/06/2012 16:36 THE UNKNOWN ENESCU VOLUME ONE: MUSIC FOR VIOLIN by Malcolm MacDonald Pastorale, Menuet triste et Nocturne, Sarabande, Sérénade lointaine, Andantino malinconico, Airs dans le genre roumain, Fantaisie concertante and Aria and Scherzino recorded in the ‘Mihail Jora’ Pablo Casals called George Enescu ‘the greatest musical phenomenon since Mozart’.1 As Concert Hall, Radio Broadcasting House, Romanian Radio, Bucharest, 5–7 June 2005 a composer, he was best known for a few early, colourfully ‘nationalist’ scores such as the Recording engineer: Viorel Ioachimescu Romanian Rhapsodies. -

ARTES Vol. 12

UNIVERSITY OF ARTS “GEORGE ENESCU” IAŞI FACULTY OF PERFORMING, COMPOSITION AND THEORETICAL MUSIC STUDIES RESEARCH CENTRE “ŞTIINŢA MUZICII” ARTES vol. 12 ARTES PUBLISHING HOUSE 2012 RESEARCH CENTRE “ŞTIINŢA MUZICII" Editor in Chief: Professor PhD Laura Otilia Vasiliu Editorial Board: Professor PhD Gheorghe Duţică, University of Arts “George Enescu” Iaşi Associate Professor PhD Victoria Melnic, Academy of Music, Theatre and Fine Arts, Chişinău (Republic of Moldova) Professor PhD Maria Alexandru, “Aristotle” University of Thessaloniki, Greece Professor PhD Valentina Sandu Dediu, National University of Music Bucharest Editorial Team: Professor Liliana Gherman Lecturer PhD Gabriela Vlahopol Lecturer PhD Diana-Beatrice Andron Cover design: Bogdan Popa ISSN 2344-3871 ISSN-L 2344-3871 © 2012 Artes Publishing House Str. Horia nr. 7-9, Iaşi, România Tel.: 0040-232.212.549 Fax: 0040-232.212.551 e-mail: [email protected] The rights on the present issue belong to Artes Publishing House. Any partial or whole reproduction of the text or the examples will punished according to the legislation in force. C O N T E N T S A. Research papers presented within the National Musicology Symposium - Stylistic indentity and contexts of Romanian music, 5th edition, 2011 ROMANIAN MUSIC IN THE 20TH CENTURY: HOW? WHERE? WHY? Associate Professor PhD. Carmen Chelaru,”George Enescu” University of Arts, Iasi, Romania……………………………………………………………………….7 THE INFLUENCE OF CENTRAL EUROPEAN MUSICAL CULTURE ON MODERN ROMANIAN COMPOSITION. CASE STUDY: PASCAL BENTOIU Professor PhD. Laura Vasiliu,”George Enescu” University of Arts, Iasi, Romania………………………………………………………………….…….…23 PASCAL BENTOIU – EMINESCIANA III. A “CONCERTO FOR ORCHESTRA” OR THE DISSIMULATION OF A SYMPHONY? Music teacher PhD. Luminiţa Duţică, The National College of Arts “Octav Băncilă”, Iasi, Romania……………………………………………………….......35 “AN ENCOMIUM TO SYMMETRY”. -

CREAŢII „Săteasca” Enesciană Şi Constelaţia Ei

Revista MUZICA Nr. 8 / 2015 CREAŢII „Săteasca” enesciană şi constelaţia ei Vasile Vasile Dacă uvertura, poemul simfonic şi simfonia programatică au oscilat, în ceea ce priveşte orientarea tematică, între solida ancorare în trecutul istoric românesc (având în vedere uverturile naționale, Ştefan cel Mare, Cetatea Neamţului etc.) sau în oglindirea frumuseţilor patriei și a spiritualității ei (Pe şesul Moldovei, Hanul Ancuței - cu ultimul tablou – Cu steaua, sau având integrată melodia Mioriței, alături de melodii de joc - creații ale aceluiași Zirra), Amintiri din Carpaţi etc.), în orientarea spre subiecte mitologice (Marsyas de Alfonso Castaldi, Acteon, Didona de Alfred Alessandrescu, Vrăjile Armidei de Ion Nonna Otescu etc.) şi spre cele cu caracter filosofic (Eroul fără glorie cu ale sale trei părţi intitulate Între bine şi rău, Între tot şi nimic, Între viaţă şi moarte de Alfonso Castaldi), suita, mai ales cea programatică, va deveni principalul mijloc de dezvoltare a unei serioase orientări naţionale în muzica simfonică românească. După ce şi-a plătit şi ea tributul față de forma neoclasică şi neoromantică (Suita în stil vechi pentru pian (1897), Suita pentru orchestră nr. 2 (1915), ambele de George Enescu, Suita în stil clasic (1925) de Ion Ghiga şi după anumite tatonări şi abordări ale genului, înţeles ca o reuniune de dansuri românești (suita simfonică – Impresii româneşti (1913) de Alfonso Castaldi, Suita muntenească (1923) de Ion Borgovan, Suita Carpatica (1923) de Paul Richter, suita se apropie - ca şi genul muzical - dramatic -

The Iasi School of Musicology

Înv ăţământ, Cercetare, Creaţie (Education, Research, Creation) Volume I THE IASI SCHOOL OF MUSICOLOGY Author: Associate Professor PhD. Ruxandra MIREA Ovidius University of Constanta Faculty of Arts Abstract Music proves to be an axis of the human spirituality which establishes a connection between the ephemerality and eternity. By means of vibrational energy, music, which is art and science alike, expresses, builds, uplifts and transcends the experiences and the feelings of any human being endowed with conscience. Musicology is the science which comprises the complex music, in a practical and teorethical way, diachronical and synthetical, and also esthetical way. The musicologist is the complex artistic personality which sums all the knowledge of these subjects, subjects which interpenetrate. In time, musicologists from Iasi, have intensivly manifested their intelectual authority. They represent the third fulcrum, grographically and spiritually, of a third that fulfills the harmony of the contraries, Bucharest, Cluj, Iasi: Theodor T. Burada (1839-1923), Eduard Caudella (1841-1924), Titus Cerne (1859-1910), George Pascu (1912-1996), Mihail Cozmei (n.1931), Liliana Gherman (b. 1939), Laura Otilia Vasiliu (n.1958). Keywords: music, musicologist, monografies, composer, magazines, lexicography, symposium, etnography, instruments, organologie. 1. The art of musicology Music proves to be an axis of the human spirituality which establishes a connection between the ephemerality and eternity. By means of vibrational energy, music, which is art and science alike, expresses, builds, uplifts and transcends the experiences and the feelings of any human being endowed with conscience. From an ethimological point of view, the word music originates from the triad musaion-museon-muse, which represents the nine protecting gods of the arts and sciences, from Parnas, Pind and Elicone. -

George Enescu's Concertstück for Viola and Piano

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2011 George Enescu's Concertstück for viola and piano: a theoretical analysis within the composer's musical legacy Simina Alexandra Renea Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Renea, Simina Alexandra, "George Enescu's Concertstück for viola and piano: a theoretical analysis within the composer's musical legacy" (2011). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 389. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/389 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. GEORGE ENESCU’S CONCERTSTÜCK FOR VIOLA AND PIANO: A THEORETICAL ANALYSIS WITHIN THE COMPOSER’S MUSICAL LEGACY A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts In The School of Music by Simina Alexandra Renea B.M., National University of Music, Bucharest (Romania), 2000 M.M., Southeastern Louisiana University, 2005 December, 2011 To my parents, LUMINITA and LUCRETIU ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS To my best friends Emanuela Lacraru, Lloyd Thomas, Hannah‐Phyllis Urdea‐Marcus, Vasil Cvetkov, and Irina Cunev, for your help and moral support. To Matthew Daline, for encouraging me to work on this monograph’s topic and guiding me through the research process. -

George Enescu

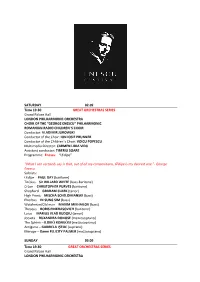

SATURDAY 02.09 Time 19.30 GREAT ORCHESTRAS SERIES Grand Palace Hall LONDON PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA CHOIR OF THE “GEORGE ENESCU” PHILHARMONIC ROMANIAN RADIO CHILDREN’S CHOIR Conductor: VLADIMIR JUROWSKI Conductor of the Choir: ION IOSIF PRUNNER Conductor of the Children’s Choir: VOICU POPESCU Multimedia Director: CARMEN LIDIA VIDU Assistant conductor: TIBERIU SOARE Programme: Enescu – “Œdipe” “What I can certainly say is that, out of all my compositions, Œdipe is my dearest one.”- George Enescu Soloists: Œdipe – PAUL GAY (baritone) Tirésias – Sir WILLARD WHITE (bass-baritone) Créon – CHRISTOPHER PURVES (baritone) Shephard – GRAHAM CLARK (tenor) High Priest – MISCHA SCHELOMIANSKI (bass) Phorbas – IN SUNG SIM (bass) Watchman/Old man – MAXIM MIKHAILOV (bass) Theseus – BORIS PINKHASOVICH (baritone) Laius – MARIUS VLAD BUDOIU (tenor) Jocasta – RUXANDRA DONOSE (mezzosoprano) The Sphinx – ILDIKÓ KOMLÓSI (mezzosoprano) Antigone – GABRIELA IŞTOC (soprano) Mérope – Dame FELICITY PALMER (mezzosoprano) SUNDAY 03.09 Time 19.30 GREAT ORCHESTRAS SERIES Grand Palace Hall LONDON PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA Conductor: VLADIMIR JUROWSKI Soloist: CHRISTIAN TETZLAFF – violin Programme: Wagner – “Tristan und Isolde”. Prelude to Act 3 Berg – Concerto for violin and orchestra (1935) Shostakovich – Symphony No.11 in G minor Opus. 103 (1905) MONDAY 04.09 Time 20.00 GREAT ORCHESTRAS SERIES Grand Palace Hall RUSSIAN NATIONAL ORCHESTRA RADIO ACADEMIC CHOIR Conductor: MIKHAIL PLETNEV Conductor of the choir: CIPRIAN ȚUȚU Soloist: NIKOLAI LUGANSKY – piano Programme: Enescu – “Isis” Poem (1923, orchestrated by Pascal Bentoiu, according to the composer's sketches) “The Isis poem is a mysterious work, impregnated with Œdipe effluvia, as well as an unmistakeable Tristanesque air, and – while it is no “music portrait” – it probably contains a tribute […] of the author to the person he loved most in this lifetime.” (Pascal Bentoiu, Breviar enescian) Prokofiev – Concerto no. -

Developmental and Stylistic Consistency in Selected Choral Works of Felicia Donceanu (B

ALEXANDER, CORY THOMAS, D.M.A. Developmental and Stylistic Consistency in Selected Choral Works of Felicia Donceanu (b. 1931). (2011) Directed by Dr. Welborn E. Young, 68 pp. The music of Felicia Donceanu (b. 1931) is well known by music scholars in Romania. Donceanu’s work has won numerous accolades including honorable mention at the International Composition Competition in Mannheim, Germany, in 1961, the prize of the Union of Composers and Musicologists of Romania seven times between 1983 and 1997, and the George Enescu prize in 1984. Donceanu’s colleagues regard her Romanian-language art songs to be among the finest examples of the genre. Donceanu has composed for nearly every instrumental genre, but solo vocal and choral compositions comprise the majority of her output. Paula Boire discussed Donceanu’s art songs in the four-volume text, A Comprehensive Study of Romanian Art Song, but Donceanu’s choral works remain largely unexplored. Donceanu’s first choral compositions date from 1968, and her choral oeuvre includes more than forty compositions written over several decades. Despite this, she considers dates of composition to be irrelevant and has stated that her works neither exhibit stylistic development nor fit into creative periods. Analyses of five representative choral compositions: “Inscripţie” from Trei poeme corale (1968), Rodul bun (1982), Ritual de Statornicie (1987), Tatăl nostru (1990), and Clopote la soroc (1996), reveal this consistency of style as it occurs in Donceanu’s choral works. DEVELOPMENTAL AND STYLISTIC CONSISTENCY IN SELECTED CHORAL WORKS OF FELICIA DONCEANU (B. 1931) by Cory Thomas Alexander A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts Greensboro 2011 Approved by ____________________________________ Committee Chair To Bethany and Emma. -

ARTES. REVISTĂ DE MUZICOLOGIE Vol

UNIVERSITATEA DE ARTE „GEORGE ENESCU” IAŞI FACULTATEA DE INTERPRETARE, COMPOZIŢIE ŞI STUDII MUZICALE TEORETICE CENTRUL DE CERCETARE „ŞTIINŢA MUZICII” ARTES. REVISTĂ DE MUZICOLOGIE vol. 15 EDITURA ARTES 2015 CENTRUL DE CERCETARE „ŞTIINŢA MUZICII” ARTES. REVISTĂ DE MUZICOLOGIE • Redactor şef – Prof. univ. dr. Laura Vasiliu, Universitatea de Arte „George Enescu” Iași, România • Senior editor – Prof. univ. Liliana Gherman, Universitatea de Arte „George Enescu” Iași, România COMITETUL ȘTIINȚIFIC • Prof. univ. dr. Gheorghe Duțică, Universitatea de Arte „George Enescu” Iași, România • Prof. univ. dr. Maria Alexandru, “Aristotle” University of Thessaloniki, Grecia • Prof. univ. dr. Valentina Sandu-Dediu, Universitatea Națională de Muzică București, România • Prof. univ. dr. Maria Alexandru, “Aristotle” University of Thessaloniki, Grecia • Prof. univ. dr. Pavel Pușcaș, Academia de Muzică „Gheorghe Dima”, Cluj-Napoca, România • Prof. univ. dr. Mirjana Veselinović-Hofman, University of Arts in Belgrade, Serbia • Prof. univ. dr. Victoria Melnic, Academia de Muzică, Teatru și Arte plastice, Chișinău, Republica Moldova • Prof. univ. dr. Violeta Dinescu, “Carl von Ossietzky” Universität Oldenburg, Germania • Prof. univ. dr. Nikos Maliaras, Universitatea Națională și Capodistriană, Atena, Grecia • Lect. univ. dr. Emmanouil Giannopoulos, “Aristotle” University of Thessaloniki, Grecia ECHIPA REDACŢIONALĂ • Conf. univ. dr. Irina Zamfira Dănilă, Universitatea de Arte „George Enescu” Iași, România • Lect. univ. dr. Diana-Beatrice Andron, Universitatea de Arte „George Enescu” Iași, România • Lect. univ. dr. Rosina Caterina Filimon, Universitatea de Arte „George Enescu” Iași, România • Lect. univ. dr. Gabriela Vlahopol, Universitatea de Arte „George Enescu” Iași, România ISSN 1224-6646 ISSN-L 1224-6646 Traducători Asist. univ. drd. Maria Cristina Misievici Drd. Emanuel Vasiliu DTP Ing. Victor Dănilă Carmen Antochi www.artes-iasi.ro © 2015 Editura Artes Str. -

Decada Muzicii Româneşti 1-10 Noiembrie 2010

Revista MUZICA Nr.4/2010 CUPRINS PASCAL BENTOIU LA ANIVERSAREA A 90 DE ANI DE LA ÎNFIINŢAREA UNIUNII ......... 5 OCTAVIAN LAZĂR COSMA GÂNDURI LA ANIVERSAREA UNIUNII .......................................... 12 ANTIGONA RĂDULESCU INTERVIU CU PREŞEDINTELE UCMR, COMPOZITORUL ADRIAN IORGULESCU ...................................... 23 GHEORGHE FIRCA UNIUNEA COMPOZITORILOR – ASOCIAŢIE PROFESIONALĂ ŞI CLUB ELITIST ........................................................................... 29 VASILE TOMESCU SUB SEMNUL DEMNITĂŢII ŞI SOLIDARITĂŢII ............................... 36 VASILE VASILE SOCIETATEA COMPOZITORILOR ROMÂNI, MOMENT CRUCIAL ÎN ISTORIA MUZICII ROMÂNEŞTI ŞI CONSECINŢELE ASUPRA CULTURII NAŢIONALE ................................................................. 41 DAN DEDIU CE ROL ARE UCMR ÎN CONTEMPORANEITATE? .......................... 90 GEORGE BALINT GÂNDURI DESPRE ROSTUL COMISIEI DE SPECIALITATE A UCMR . 97 HORIA MOCULESCU MÂNDRIA DE A FI MEMBRU AL UCMR ..................................... 102 1 https://biblioteca-digitala.ro Revista MUZICA Nr. 4/2010 0 NICOLAE GHEORGHIȚĂ MUZICOLOGIA BIZANTINĂ ÎN PREOCUPĂRILE UCMR ............... 104 DESPINA PETECEL THEODORU DECADA MUZICII ROMÂNEŞTI 1-10 NOIEMBRIE 2010 .............. 111 VIOREL COSMA MUZICIENI ÎN TEXTE ŞI DOCUMENTE (XV) SOCIETATEA COMPOZITORILOR ROMÂNI (1920) ...................... 124 2 https://biblioteca-digitala.ro Revista MUZICA Nr.4/2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS PASCAL BENTOIU THE 90TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE COMPOSER'S SOCIETY ................ 5 OCTAVIAN LAZĂR COSMA REFLEXION