Developmental and Stylistic Consistency in Selected Choral Works of Felicia Donceanu (B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

George Enescu, Posthumously Reviewed

George Enescu, Posthumously Reviewed Va lentina SANDU-DEDIU National University of Music Bucharest Strada Știrbei Vodă 33, București, Ro-010102 Romania New Europe College Bucharest Strada Plantelor 21, București, Ro-023971 Romania E-mail: [email protected] (Received: November 2017; accepted: January 2018) Abstract: This essay tackles some aspects related to the attitude of the Romanian officials after George Enescu left his country definitively (in 1946). For example, re- cent research through the archives of the former secret police shows that Enescu was under the close supervision of Securitate during his last years in Paris. Enescu did not generate a compositional school during his lifetime, like for instance Arnold Schoen- berg did. His contemporaries admired him, but each followed their own path and had to adapt differently to an inter-war, then to a post-war, Communist Romania. I will therefore sketch the approach of younger composers in relation to Enescu (after 1955): some of them attempted to complete unfinished manuscripts; others were in fluenced by ideas of Enescu’s music. The posthumous reception of Enescu means also an in- tense debate in the Romanian milieu about his “national” and “universal” output. Keywords: Securitate, socialist realism in Romania, “national” and “universal,” het- erophony, performance practice It is a well-known fact that George Enescu did not create a school of composition during his lifetime, neither in the sense of direct professor–student transmission of information, as was the case in Vienna with Arnold Schoenberg, nor in the wider sense of a community of ideas or aesthetic principles. His contemporaries admired him, but they each had their own, well-established stylistic paths; in the Stalinist post-war period, some of them subordinated their work to the ideological requirements of socialist realism and it was generally discouraged to discern the subtle, but substantial renewals of Enescu’s musical language. -

Constante Şi Deschideri În Cvartetele De Coarde Ale Lui Wilhelm Georg Berger (I)

MUZICA nr.1/2010 CREAŢII Monica CENGHER Constante şi deschideri în cvartetele de coarde ale lui Wilhelm Georg Berger (I) Interesul lui W.G.Berger pentru genurile instrumentale verificate de proba îndelungată a istoriei, primordiale fiind cvartetul de coarde şi simfonia alături de concertul instrumental şi sonată, s-a concretizat într-o vastă operă de autor, elaborată în spiritul unui virtual dar ingenios dialog cu valorile supreme ale culturii. Sintagma goetheană “dacă vrei să păşeşti în infinit, parcurge finitul din toate direcţiile” este emblematică demersului său artistic. Vocaţia renascentistă de a iscodi concreteţea artei muzicale din mai multe ipostaze (istorice, estetice, matematice, componistice şi nu în ultimul rând interpretative), a fost dublată de însuşirile unei personalităţi profunde, înzestrată cu o fină inteligenţă, generozitate şi fire contemplativă cu nuanţe de blândeţe. “Fenomenul W. Berger – căci a fost un fenomen cu totul neobişnuit – nu s-a produs în locuri obscure sau ascunse, ci în plină lumină”1- releva pe un ton admirativ Pascal Bentoiu. Această forţă iradiantă însoţită de bucuria revelaţiei pe care i-a oferit-o cunoaşterea, l-au călăuzit întreaga viaţă, conturându-i opera de autor pe dimensiuni monumentale, masive şi de o anvergură nemaiîntâlnită la noi. Abundenţa cu care dădea la iveală creaţiile muzicale şi lucrările muzicologice reprezintă amplitudinea aspiraţiilor sale de largă cuprindere, în care erudiţia naşte imaginaţie şi detaliul se generalizează în concepte abstracte. Există o cadenţă în evoluţia lui W.G.Berger. Pe de o parte urmăreşte împlinirea unor ţeluri pe planul gândirii despre muzică, pornind de la analiza resorturilor intime ale fenomenului muzical, conturând liniile de forţă ale curentelor şi mentalităţilor artistice; pe de altă parte, se defineşte printr-o consistentă gândire componistică cu deschideri atât către tradiţii cât şi spre înnoiri. -

Giuseppe Verdi

Giuseppe Verdi Rigoletto Libretto: Francesco Maria Piave Literarische Vorlage: Victor Hugo: Le roi s’amuse Ort und Zeit der Handlung: 16. Jahrhundert in Mantua, Italien Uraufführung: 11. März 1851 im Teatro La Fenice, Venedig Medien der Stadtbibliothek – Ebene Musik zusammengestellt von Jasmin Salzer Stand Mai 2015 Stadtbibliothek Stuttgart Mailänder Platz 1 70173 Stuttgart +49 (0) 711/216-91100 Öffnungszeiten Montag bis Samstag 9 bis 21 Uhr Allgemeine Informationen zur Oper – online http://www.opera-guide.ch/opera.php?id=394&uilang=de http://www.operone.de/opern/rigoletto.html Libretto Online: http://www.opera-guide.ch/opera.php?id=394&uilang=de Verdi, Giuseppe: Rigoletto : Melodramma in tre atti. Oper in drei Akten. Textbuch italienisch - deutsch / Übers. von Elena Sterbini. Nachwort von Albert Gier. - Stuttgart : Reclam, 1998. - 119 S. - (Universal-Bibliothek ; Nr. 9704) ISBN 3-15-009704-5 Systematik: Sbt 2 Ver (1.OGC34) Literatur über Giuseppe Verdi bzw. sein Opernwerk: Brandenburg, Daniel: Verdi, Rigoletto. - Kassel : Bärenreiter, 2012. - 135 S. (Opernführer kompakt) ISBN 978-3-7618-2225-8 Systematik: Sbm 82 Verdi, G. Bra (1.OGC36) Henze-Döhring, Sabine: Verdis Opern : ein musikalischer Werkführer. - Orig.-Ausg. - München : Beck, 2013. - 128 S. - (Beck'sche Reihe ; 2221 : Wissen - Musik) ISBN 978-3-406-64606-5 Systematik: Sbm 82 Verdi, G. Hen (1.OGC36) Schwandt, Christoph: Giuseppe Verdi : die Biographie. - Aktualisierte Neuausg., 1. Aufl. - Frankfurt am Main : Insel-Verl., 2013. - 303 S. (Insel-Taschenbuch ; 4211) ISBN 978-3-458-35911-1 Systematik: Sbm 82 Verdi, G. Schwa (1.OGC38) Stegemann, Benedikt: Orpheus [Hörbuch] : der klingende Opernführer / Sprecher: Peter Lerchbaumer. - München : Ricordi, 2007 Bd. -

LUNI 30 August 2021 0.00 Nocturn Jazz. Realizator Simona Dumitriu 1.00

LUNI 20 septembrie 2021 1.0 Nocturn jazz. Realizator Dan Ghineraru 1.00 – 7.00 Notturno. Coordonator Ion Cristian Niţu. Realizator Doina Constantinescu. Repere: *Concertul nopţii (ora 3.00): Orchestra Simfonică a Radioteleviziunii Italiene, dirijor Daniele Gatti; *Alte repere: William Babell – Sonata nr. 1 în Si bemol major pentru vioară şi clavecin (ora 1.05); Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart – Cvartetul K 298 în La major (ora 2.29); Erich Wolfgang Korngold – Cvintetul op. 15 în Mi major (ora 4.28); Johan Helmich Roman – Simfonia nr. 20 în mi minor (ora 6.01) 7.00 Musica viva. Realizator Gabriel Marica. *Meteo (orele 7.10; 8.10; 9.10); *Concurs (orele 7.30; 8.30); *Ştiri muzicale (orele 8.00 şi 9.00); 9.55 Promo 10.00 Arpeggio. Realizator Marina Nedelcu. Joseph Haydn – Simfonia nr. 102 în Si bemol major (”Les Musiciens du Louvre”, dirijor Marc Minkowski); Charles Tessier – ”Carnete de călătorie” (”Le Poeme Harmonique”, dirijor Vincent Dumestre); Robert Schumann – Concertul op.129 în la minor pentru violoncel şi orchestră (Steven Isserlis, Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie, dirijor Christoph Eschenbach); Claude Debussy – «Stampe» pentru pian (Rafał Blechacz); Edvard Grieg – Suita nr. 2 op. 55 “Peer Gynt” (Orchestra Simfonică din Göteborg, dirijor Neeme Jarvi); Ralph Towner – ”Joyful departure” (”Oregon”) 11.55 Promo 12.00 Interpretul zilei. Realizator Petre Fugaciu. Pianistul Glenn Gould. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart – Sonata nr. 7 KV 309 în Do major; Johann Sebastian Bach – Variațiunile Goldberg BWV 988 13.00 Polifonii. Realizator Sorina Bobeico. Franz Schubert – Simfonia nr. 3 D 200 în Re major (Orchestra Filarmonicii din Berlin, dirijor Karl Böhm); Johann Sebastian Bach - Partita nr. -

Staged Treasures

Italian opera. Staged treasures. Gaetano Donizetti, Giuseppe Verdi, Giacomo Puccini and Gioacchino Rossini © HNH International Ltd CATALOGUE # COMPOSER TITLE FEATURED ARTISTS FORMAT UPC Naxos Itxaro Mentxaka, Sondra Radvanovsky, Silvia Vázquez, Soprano / 2.110270 Arturo Chacon-Cruz, Plácido Domingo, Tenor / Roberto Accurso, DVD ALFANO, Franco Carmelo Corrado Caruso, Rodney Gilfry, Baritone / Juan Jose 7 47313 52705 2 Cyrano de Bergerac (1875–1954) Navarro Bass-baritone / Javier Franco, Nahuel di Pierro, Miguel Sola, Bass / Valencia Regional Government Choir / NBD0005 Valencian Community Orchestra / Patrick Fournillier Blu-ray 7 30099 00056 7 Silvia Dalla Benetta, Soprano / Maxim Mironov, Gheorghe Vlad, Tenor / Luca Dall’Amico, Zong Shi, Bass / Vittorio Prato, Baritone / 8.660417-18 Bianca e Gernando 2 Discs Marina Viotti, Mar Campo, Mezzo-soprano / Poznan Camerata Bach 7 30099 04177 5 Choir / Virtuosi Brunensis / Antonino Fogliani 8.550605 Favourite Soprano Arias Luba Orgonášová, Soprano / Slovak RSO / Will Humburg Disc 0 730099 560528 Maria Callas, Rina Cavallari, Gina Cigna, Rosa Ponselle, Soprano / Irene Minghini-Cattaneo, Ebe Stignani, Mezzo-soprano / Marion Telva, Contralto / Giovanni Breviario, Paolo Caroli, Mario Filippeschi, Francesco Merli, Tenor / Tancredi Pasero, 8.110325-27 Norma [3 Discs] 3 Discs Ezio Pinza, Nicola Rossi-Lemeni, Bass / Italian Broadcasting Authority Chorus and Orchestra, Turin / Milan La Scala Chorus and 0 636943 132524 Orchestra / New York Metropolitan Opera Chorus and Orchestra / BELLINI, Vincenzo Vittorio -

Toscanini in Stereo a Report on RCA's "Electronic Reprocessing"

Toscanini in Stereo a report on RCA's "electronic reprocessing" MARCH ERS 60 CENTS FOR STEREO FANS! Three immortal recordings by Arturo Toscanini and the NBC Symphony have been given new tonal beauty and realism by means of a new RCA Victor engineering development, Electronic Stereo characteristics electronically, Reprocessing ( ESR ) . As a result of this technique, which creates stereo the Toscanini masterpieces emerge more moving, more impressive than ever before. With rigid supervision, all the artistic values have been scrupulously preserved. The performances are musically unaffected, but enhanced by the added spaciousness of ESR. Hear these historic Toscanini ESR albums at your dealer's soon. They cost no more than the original Toscanini monaural albums, which are still available. Note: ESR is for stereo phonographs only. A T ACTOR records, on the 33, newest idea in lei RACRO Or AMERICA Ask your dealer about Compact /1 CORPORATION M..00I sun.) . ., VINO .IMCMitmt Menem ILLCr sí1.10 ttitis I,M MT,oMC Mc0001.4 M , mi1MM MCRtmM M nm Simniind MOMSOMMC M Dvoìtk . Rn.psthI SYMPHONY Reemergáy Ravel RRntun. of Rome Plue. of Rome "FROM THE NEW WORLD" Pictures at an Exhibition TOSCANINI ARTURO TOSCANINI Toscanini NBC Symphony Orchestra Arturo It's all Empire -from the remarkable 208 belt- driven 3 -speed turntable -so quiet that only the sound of the music distinguishes between the turntable at rest and the turntable in motion ... to the famed Empire 98 transcription arm, so perfectly balanced that it will track a record with stylus forces well below those recommended by cartridge manufacturers. A. handsome matching walnut base is pro- vided. -

Only Performers Are Included Through the 1980-1981 Season

*Only performers are included through the 1980-1981 season. Both performers and repertoire are included beginning with the 1981-1982 season. PRESTIGE CONCERTS AT 8:30 P.M. IN THE LITTLE THEATRE OF THE COLUMBUS GALLERY OF FINE ARTS EXCEPT WHEN NOTED: 1948-1949 1948 November 29 (afternoon & eve) Walden String Quartet, Resident at the University of Illinois December 22 Walden String Quartet & Donald McGinnis, clarinet December 29 Ernst von Dohnanyi, piano 1949 January 13 and February 8 Walden String Quartet March 11 Walden String Quartet & Evelyn Garvey, piano 1949-1950 1949 December 14 Walden String Quartet 1950 January 9 Walden String Quartet February 11 Frances Magnes, violin & Malcolm Frager, piano March 13 Walden String Quartet March 30 Ernst von Dohnanyi, piano April 5 Walden String Quartet & Donald McGinnis, clarinet May 8 Walden String Quartet & Evelyn Garvey, piano 1950-1951 1950 November 15 Roland Hayes, tenor 1951 February 7 Nell Schelky Tangeman, soprano & Merrill Brockway, piano March 3 Frances Magnes, violin & David Garvey, piano 1951-1952 1951 October 18 Roland Hayes, tenor & Reginald Boardman, piano November 3 Soulima Stravinsky, piano (son of Igor) December 4 Berkshire String Quartet, Resident at Indiana University 1952 January 10 Frances Magnes, violin & David Garvey, piano February 9 David Garvey, piano March 8 Berkshire String Quartet 1952-1953 1952 October 27 Roland Hayes, tenor & Reginald Boardman, piano November 20 Juilliard String Quartet December 8 Luigi Silva, cello & Joseph Wolman, piano 1953 January 24 Beveridge -

The Metropolitan Opera Presents Aida in HD

Visions and Voices and the USC Libraries have collaborated to create a series of resource guides that allow you to build on your experiences at many Visions and Voices events. Explore the resources listed below and continue your journey of inquiry and discovery! USC LIBRARIES RESOURCE GUIDE VISIONS AND VOICES and the USC SCHOOL OF CINEMATIC ARTS, in conjunction with the METROPOLITAN OPERA in New York, present the HD telecast of Giuseppe Verdi’s Aida. To help you learn more about Verdi’s masterpiece, ROSS SCIMECA of the USC LIBRARIES has selected the following resources. Introduction Giuseppe Verdi composed 28 operas during his lifetime. Aida is the 26th, followed by his late masterpieces, Otello and Falstaff. What is unique about Aida is that it is a grand opera, meaning it features extended choruses, ballets and marches composed in a theatrically spectacular style. Like Don Carlos, which preceded Aida by five years and premiered at the Paris Opera, Verdi brilliantly integrated these spectacular elements with the vocal elements of traditional opera. Camille du Locle took the plot for his French-language libretto for Aida from the work of Egyptologist Mariette Bey. The libretto was later translated into Italian verse by Antonio Ghislanzoni. Commissioned by the Khedive of Egypt, Aida premiered at the Italian Theatre in Cairo on December 24, 1871. It was a sensational success, as it was two months later at Milan’s La Scala. The opera reached New York’s Academy of Music on November 26, 1873. You can find the Italian-language libretto of Aida and an English translation in the Opera Classics Library by clicking on the Databases tab at: www.usc.edu/libraries/eresources. -

AM-2015-12.Pdf

Serie nouã ACTUALITATEA decembrie12 2015 (CLXXIII) 48 pagini MUZICAL~ ISSN MUZICAL~ 1220-742X REVISTĂ LUNARĂ A UNIUNII COMPOZITORILOR ŞI MUZICOLOGILOR DIN ROMÂNIA D i n s u m a r: Uniunea Compozitorilor şi Muzicologilor la 95 de ani Festivalul Internaţional MERIDIAN Festivalul INTRADA, Timişoara Danube Jazz & Blues Festival Rock îndoliat În imagine: Constantin Brăiloiu, Alfred Alessandrescu, Lansare carte Maria Dragomiroiu George Enescu, Ion Nonna Otescu, Mihail Jora Recunoaştere Preşedintele României Klaus Johannis a înmânat, în cadrul ceremoniei din data de 05.11.2015, UNIUNII COMPOZITORILOR ŞI MUZICOLOGILOR DIN ROMÂNIA (UCMR), cu prilejul aniversării a 95 de ani de la înfiinţarea Societăţii Compozitorilor Români (precursoarea UCMR) şi a aniversării a 20 de ani de la constituirea Alianţei Naţionale a Uniunilor de Creaţie (ANUC), Ordinul „MERITUL CULTURAL” în grad de „OFIŢER”. În argumentarea aferentă distincţiei se menţionează că aceasta se conferă în semn de înaltă apreciere pentru implicarea directă şi constantă în organizarea şi promovarea manifestărilor muzicale, pentru meritele deosebite avute la susţinerea patrimoniului clasic autohton, a creaţiei muzicale contemporane, contribuind astfel la afirmarea internaţională a compozitorilor şi muzicologilor români. DIN SUMAR UCMR la 95 de ani................................1-10 Interviu cu dl. Ulpiu Vlad....................11-12 Festivalul internaţional MERIDIAN.....13-27 Conferinţa OPERA EUROPA.................27-28 Tatiana Lisnic la ONB..........................28-29 Concerte sub... lupă.................................31 Corespondenţă de la Oldenburg...........32-33 Festivalul INTRADA.............................34-35 “In Memoriam #colectiv”....................36-37 “Danube Jazz & Blues Festival”...........38-39 Rock îndoliat......................................42-43 Lansare carte Maria Dragomiroiu........44-45 Discuri................................................46-47 Muzica pe micul ecran.............................48 ACTUALITATEA MUZICALĂ Nr. 12 Decembrie 2015 1 UCMR 95 timp de răzBOI. -

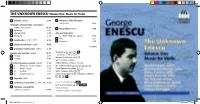

THE UNKNOWN ENESCU Volume One: Music for Violin

THE UNKNOWN ENESCU Volume One: Music for Violin 1 Aubade (1899) 3:46 17 Nocturne ‘Villa d’Avrayen’ (1931–36)* 6:11 Pastorale, Menuet triste et Nocturne (1900; arr. Lupu)** 13:38 18 Hora Unirei (1917) 1:40 2 Pastorale 3:30 3 Menuet triste 4:29 Aria and Scherzino 4 Nocturne 5:39 (c. 1898–1908; arr. Lupu)** 5:12 19 Aria 2:17 5 Sarabande (c. 1915–20)* 4:43 20 Scherzino 2:55 6 Sérénade lointaine (1903) 4:49 TT 79:40 7 Andantino malinconico (1951) 2:15 Sherban Lupu, violin – , Prelude and Gavotte (1898)* 10:21 [ 20 conductor –, – 8 Prelude 4:32 Masumi Per Rostad, viola 9 Gavotte 5:49 Marin Cazacu, cello , Airs dans le genre roumain (1926)* 7:12 Dmitry Kouzov, cello , , 10 I. Moderato (molto rubato) 2:06 Ian Hobson, piano , , , , , 11 II. Allegro giusto 1:34 Ilinca Dumitrescu, piano , 12 III. Andante 2:00 Samir Golescu, piano , 13 IV. Andante giocoso 1:32 Enescu Ensemble of the University of Illinois –, – 20 14 Légende (1891) 4:21 , , , , , , DDD 15 Sérénade en sourdine (c. 1915–20) 4:21 –, –, –, , – 20 ADD 16 Fantaisie concertante *FIRST RECORDING (1932; arr. Lupu)* 11:04 **FIRST RECORDING IN THIS VERSION 16 TOCC 0047 Enescu Vol 1.indd 1 14/06/2012 16:36 THE UNKNOWN ENESCU VOLUME ONE: MUSIC FOR VIOLIN by Malcolm MacDonald Pastorale, Menuet triste et Nocturne, Sarabande, Sérénade lointaine, Andantino malinconico, Airs dans le genre roumain, Fantaisie concertante and Aria and Scherzino recorded in the ‘Mihail Jora’ Pablo Casals called George Enescu ‘the greatest musical phenomenon since Mozart’.1 As Concert Hall, Radio Broadcasting House, Romanian Radio, Bucharest, 5–7 June 2005 a composer, he was best known for a few early, colourfully ‘nationalist’ scores such as the Recording engineer: Viorel Ioachimescu Romanian Rhapsodies. -

06 – Spinning the Record

V: THE GOLDEN AGE, Part 2 The LP-45 boom becomes an explosion As mentioned in the previous chapter, the years 1940-1956 were so rich culturally that it is virtually impossible to describe it all in one chapter, and Americans of all economic and educational backgrounds had free or inexpensive access to music that was once only the prov- ince of the very wealthy. One should note that, in addition to the various innovations men- tioned previously, radio too was part of this free dissemination of the arts. The crown jewel of its epistle may have been Toscanini, but there were also the weekly Metropolitan Opera broadcasts sponsored by Texaco Oil, a commercial-free venue that would continue uninter- rupted until the 2003-04 season, when the company—no longer interested in promoting music that few of their customers listened to—allowed their contract to expire. And then there were two programs, independently sponsored, that brought classical, semi-classical and quasi- classical vocal music to listeners on a weekly basis, the Bell Telephone Hour and The Voice of Firestone. Both had somewhat middlebrow programming, yet they still brought such great singers as Maggie Teyte and Jussi Björling to thousands who would otherwise be unaware of their greatness. During the early LP era, too, “new” conductors (or, at least, conductors previously not known by the general public) were suddenly brought to the fore. As inventor of the LP, Co- lumbia was first, producing records by the New York Philharmonic’s new music director, Artur Rodzinski, as well as his replacement, the great Dmitri Mitropoulos (though, since the New York musicians didn’t “like” Mitropoulos, they rarely played their best for him); a re- markable Polish conductor, Paul Kletzki, in his first EMI recordings with Walter Legge’s newly-formed Philharmonia Orchestra; and the draconian Hungarian, Fritz Reiner, then the music director of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. -

ARTES Vol. 12

UNIVERSITY OF ARTS “GEORGE ENESCU” IAŞI FACULTY OF PERFORMING, COMPOSITION AND THEORETICAL MUSIC STUDIES RESEARCH CENTRE “ŞTIINŢA MUZICII” ARTES vol. 12 ARTES PUBLISHING HOUSE 2012 RESEARCH CENTRE “ŞTIINŢA MUZICII" Editor in Chief: Professor PhD Laura Otilia Vasiliu Editorial Board: Professor PhD Gheorghe Duţică, University of Arts “George Enescu” Iaşi Associate Professor PhD Victoria Melnic, Academy of Music, Theatre and Fine Arts, Chişinău (Republic of Moldova) Professor PhD Maria Alexandru, “Aristotle” University of Thessaloniki, Greece Professor PhD Valentina Sandu Dediu, National University of Music Bucharest Editorial Team: Professor Liliana Gherman Lecturer PhD Gabriela Vlahopol Lecturer PhD Diana-Beatrice Andron Cover design: Bogdan Popa ISSN 2344-3871 ISSN-L 2344-3871 © 2012 Artes Publishing House Str. Horia nr. 7-9, Iaşi, România Tel.: 0040-232.212.549 Fax: 0040-232.212.551 e-mail: [email protected] The rights on the present issue belong to Artes Publishing House. Any partial or whole reproduction of the text or the examples will punished according to the legislation in force. C O N T E N T S A. Research papers presented within the National Musicology Symposium - Stylistic indentity and contexts of Romanian music, 5th edition, 2011 ROMANIAN MUSIC IN THE 20TH CENTURY: HOW? WHERE? WHY? Associate Professor PhD. Carmen Chelaru,”George Enescu” University of Arts, Iasi, Romania……………………………………………………………………….7 THE INFLUENCE OF CENTRAL EUROPEAN MUSICAL CULTURE ON MODERN ROMANIAN COMPOSITION. CASE STUDY: PASCAL BENTOIU Professor PhD. Laura Vasiliu,”George Enescu” University of Arts, Iasi, Romania………………………………………………………………….…….…23 PASCAL BENTOIU – EMINESCIANA III. A “CONCERTO FOR ORCHESTRA” OR THE DISSIMULATION OF A SYMPHONY? Music teacher PhD. Luminiţa Duţică, The National College of Arts “Octav Băncilă”, Iasi, Romania……………………………………………………….......35 “AN ENCOMIUM TO SYMMETRY”.