Detection of Capripoxvirus DNA Using a Novel Loop-Mediated Isothermal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recombinant and Chimeric Viruses

Recombinant and chimeric viruses: Evaluation of risks associated with changes in tropism Ben P.H. Peeters Animal Sciences Group, Wageningen University and Research Centre, Division of Infectious Diseases, P.O. Box 65, 8200 AB Lelystad, The Netherlands. May 2005 This report represents the personal opinion of the author. The interpretation of the data presented in this report is the sole responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the opinion of COGEM or the Animal Sciences Group. Dit rapport is op persoonlijke titel door de auteur samengesteld. De interpretatie van de gepresenteerde gegevens komt geheel voor rekening van de auteur en representeert niet de mening van de COGEM, noch die van de Animal Sciences Group. Advisory Committee Prof. dr. R.C. Hoeben (Chairman) Leiden University Medical Centre Dr. D. van Zaane Wageningen University and Research Centre Dr. C. van Maanen Animal Health Service Drs. D. Louz Bureau Genetically Modified Organisms Ing. A.M.P van Beurden Commission on Genetic Modification Recombinant and chimeric viruses 2 INHOUDSOPGAVE RECOMBINANT AND CHIMERIC VIRUSES: EVALUATION OF RISKS ASSOCIATED WITH CHANGES IN TROPISM Executive summary............................................................................................................................... 5 Introduction............................................................................................................................................ 7 1. Genetic modification of viruses .................................................................................................9 -

25 May 7, 2014

Joint Pathology Center Veterinary Pathology Services Wednesday Slide Conference 2013-2014 Conference 25 May 7, 2014 ______________________________________________________________________________ CASE I: 3121206023 (JPC 4035610). Signalment: 5-week-old mixed breed piglet, (Sus domesticus). History: Two piglets from the faculty farm were found dead, and another piglet was weak and ataxic and, therefore, euthanized. Gross Pathology: The submitted piglet was in good body condition. It was icteric and had a diffusely pale liver. Additionally, petechial hemorrhages were found on the kidneys, and some fibrin was present covering the abdominal organs. Laboratory Results: The intestine was PCR positive for porcine circovirus (>9170000). Histopathologic Description: Mesenteric lymph node: Diffusely, there is severe lymphoid depletion with scattered karyorrhectic debris (necrosis). Also scattered throughout the section are large numbers of macrophages and eosinophils. The macrophages often contain botryoid basophilic glassy intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies. In fewer macrophages, intranuclear basophilic inclusions can be found. Liver: There is massive loss of hepatocytes, leaving disrupted liver lobules and dilated sinusoids engorged with erythrocytes. The remaining hepatocytes show severe swelling, with micro- and macrovesiculation of the cytoplasm and karyomegaly. Some swollen hepatocytes have basophilic intranuclear, irregular inclusions (degeneration). Throughout all parts of the liver there are scattered moderate to large numbers of macrophages (without inclusions). Within portal areas there is multifocally mild to moderate fibrosis and bile duct hyperplasia. Some bile duct epithelial cells show degeneration and necrosis, and there is infiltration of neutrophils within the lumen. The limiting plate is often obscured mainly by infiltrating macrophages and eosinophils, and fewer neutrophils, extending into the adjacent parenchyma. Scattered are small areas with extra medullary hematopoiesis. -

A Scoping Review of Viral Diseases in African Ungulates

veterinary sciences Review A Scoping Review of Viral Diseases in African Ungulates Hendrik Swanepoel 1,2, Jan Crafford 1 and Melvyn Quan 1,* 1 Vectors and Vector-Borne Diseases Research Programme, Department of Veterinary Tropical Disease, Faculty of Veterinary Science, University of Pretoria, Pretoria 0110, South Africa; [email protected] (H.S.); [email protected] (J.C.) 2 Department of Biomedical Sciences, Institute of Tropical Medicine, 2000 Antwerp, Belgium * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +27-12-529-8142 Abstract: (1) Background: Viral diseases are important as they can cause significant clinical disease in both wild and domestic animals, as well as in humans. They also make up a large proportion of emerging infectious diseases. (2) Methods: A scoping review of peer-reviewed publications was performed and based on the guidelines set out in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) extension for scoping reviews. (3) Results: The final set of publications consisted of 145 publications. Thirty-two viruses were identified in the publications and 50 African ungulates were reported/diagnosed with viral infections. Eighteen countries had viruses diagnosed in wild ungulates reported in the literature. (4) Conclusions: A comprehensive review identified several areas where little information was available and recommendations were made. It is recommended that governments and research institutions offer more funding to investigate and report viral diseases of greater clinical and zoonotic significance. A further recommendation is for appropriate One Health approaches to be adopted for investigating, controlling, managing and preventing diseases. Diseases which may threaten the conservation of certain wildlife species also require focused attention. -

Whole-Proteome Phylogeny of Large Dsdna Virus Families by an Alignment-Free Method

Whole-proteome phylogeny of large dsDNA virus families by an alignment-free method Guohong Albert Wua,b, Se-Ran Juna, Gregory E. Simsa,b, and Sung-Hou Kima,b,1 aDepartment of Chemistry, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720; and bPhysical Biosciences Division, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, 1 Cyclotron Road, Berkeley, CA 94720 Contributed by Sung-Hou Kim, May 15, 2009 (sent for review February 22, 2009) The vast sequence divergence among different virus groups has self-organizing maps (18) have also been used to understand the presented a great challenge to alignment-based sequence com- grouping of viruses. parison among different virus families. Using an alignment-free In the previous alignment-free phylogenomic studies using l-mer comparison method, we construct the whole-proteome phylogeny profiles, 3 important issues were not properly addressed: (i) the for a population of viruses from 11 viral families comprising 142 selection of the feature length, l, appears to be without logical basis; large dsDNA eukaryote viruses. The method is based on the feature (ii) no statistical assessment of the tree branching support was frequency profiles (FFP), where the length of the feature (l-mer) is provided; and (iii) the effect of HGT on phylogenomic relationship selected to be optimal for phylogenomic inference. We observe was not considered. HGT in LDVs has been documented by that (i) the FFP phylogeny segregates the population into clades, alignment-based methods (19–22), but these studies have mostly the membership of each has remarkable agreement with current searched for HGT from host to a single family of viruses, and there classification by the International Committee on the Taxonomy of has not been a study of interviral family HGT among LDVs. -

JOURNAL of VIROLOGY VOLUME 63 * DECEMBER 1989 NUMBER 12 Arnold J

JOURNAL OF VIROLOGY VOLUME 63 * DECEMBER 1989 NUMBER 12 Arnold J. Levine, Editor in Chief Robert A. Lamb Editor (1992) (1994) Northwestern University Princeton University Stephen P. Goff, Editor (1994) Evanston, Ill. Princeton, N.J. Columbia University Michael B. A. Oldstone, Editor (1993) Joan S. Brugge, Editor (1994) New York, N. Y. Scripps Clinic & Research University ofPennsylvania Peter M. Howley, Editor (1993) Foundation Philadelphia, Pa. National Cancer Institute La Jolla, Calif. Bernard N. Fields, Editor (1993) Bethesda, Md. Thomas E. Shenk, Editor (1994) Harvard Medical School Princeton University Boston, Mass. Princeton, N.J. EDITORIAL BOARD Rafi Ahmed (1991) Emanuel A. Faust (1990) Robert A. Lazzarini (1990) William S. Robinson (1989) James Alwine (1991) S. Jane Flint (1990) Jonathan Leis (1991) Bernard Roizman (1991) David Baltimore (1990) William R. Folk (1991) Myron Levine (1991) John K. Rose (1991) Amiya K. Banerjee (1990) Donald Ganem (1991) Arthur D. Levinson (1991) Naomi Rosenberg (1989) Tamar Ben-Porat (1990) Costa Georgopolous (1989) Maxine Linial (1991) Roland R. Rueckert (1991) Kenneth I. Berns (1991) Walter Gerhard (1989) David M. Livingston (1991) Norman P. Salzman (1990) Joseph B. Bolen (1991) Mary-Jane Gething (1990) Douglas R. Lowy (1989) Charles E. Samuel (1989) Michael Botchan (1989) Joseph C. Glorioso (1989) Malcohm Martin (1989) Priscilla A. Schaffer (1990) Thomas J. Braciale (1991) Larry M. Gold (1991) Robert Martin (1990) Sondra Schlesinger (1989) Dalius J. Briedis (1991) Hidesaburo Hanafusa (1989) Warren Masker (1990) Robert J. Schneider (1991) Michael J. Buchmeier (1989) John Hassell (1989) James McDougall (1990) Bart Sefton (1991) Robert Callahan (1991) William S. Hayward (1990) Thomas Merigan (1989) Bert L. -

Sheep and Goats

Sheep Pox and Importance Sheep pox and goat pox are contagious viral diseases of small ruminants. These Goat Pox diseases may be mild in indigenous breeds living in endemic areas, but they are often fatal in newly introduced animals. Economic losses result from decreased milk Capripoxvirus Infections, production, damage to the quality of hides and wool, and other production losses. Sheep Capripox pox and goat pox can limit trade, inhibit the development of intensive livestock production, and prevent new breeds of sheep or goats from being imported into endemic regions. Last Updated: August 2017 Etiology Sheep pox and goat pox result from infection by sheeppox virus (SPPV) or goatpox virus (GTPV), closely related members of the genus Capripoxvirus in the family Poxviridae. SPPV is mainly thought to affect sheep and GTPV primarily to affect goats, but some isolates can cause mild to serious disease in both species. SPPV and GTPV can be distinguished by a few specialized genetic tests. These tests are not widely available, and isolates are typically assigned to SPPV or GTPV based on the animal species affected during an outbreak. However, some studies suggest that this assumption is not always valid. SPPV and GTPV are closely related to lumpy skin disease virus (LSDV), a capripoxvirus that affects cattle. These three viruses cannot be distinguished by many diagnostic tests, including all tests that detect antibodies or viral antigens. Species Affected SPPV and GTPV only appear to affect sheep and goats. It seems plausible that these viruses could cause disease in wild relatives of small ruminants, but there are no reports of any infections in free-living or captive wild species. -

Evidence to Support Safe Return to Clinical Practice by Oral Health Professionals in Canada During the COVID-19 Pandemic: a Repo

Evidence to support safe return to clinical practice by oral health professionals in Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic: A report prepared for the Office of the Chief Dental Officer of Canada. November 2020 update This evidence synthesis was prepared for the Office of the Chief Dental Officer, based on a comprehensive review under contract by the following: Paul Allison, Faculty of Dentistry, McGill University Raphael Freitas de Souza, Faculty of Dentistry, McGill University Lilian Aboud, Faculty of Dentistry, McGill University Martin Morris, Library, McGill University November 30th, 2020 1 Contents Page Introduction 3 Project goal and specific objectives 3 Methods used to identify and include relevant literature 4 Report structure 5 Summary of update report 5 Report results a) Which patients are at greater risk of the consequences of COVID-19 and so 7 consideration should be given to delaying elective in-person oral health care? b) What are the signs and symptoms of COVID-19 that oral health professionals 9 should screen for prior to providing in-person health care? c) What evidence exists to support patient scheduling, waiting and other non- treatment management measures for in-person oral health care? 10 d) What evidence exists to support the use of various forms of personal protective equipment (PPE) while providing in-person oral health care? 13 e) What evidence exists to support the decontamination and re-use of PPE? 15 f) What evidence exists concerning the provision of aerosol-generating 16 procedures (AGP) as part of in-person -

Lumpy Skin Disease (Lsd)

EAZWV Transmissible Disease Fact Sheet Sheet No. 39 LUMPY SKIN DISEASE (LSD) ANIMAL TRANS- CLINICAL SIGNS FATAL TREATMENT PREVENTION GROUP MISSION DISEASE? & CONTROL AFFECTED cattle - insects - fever No None available In houses - (contact) - skin nodules - swollen lymph In zoos nodes avoid contact - (systemic with insect reactions) vectors, vaccination Fact sheet compiled by Last update S. Geerts, Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp, January 2009 Belgium Fact sheet reviewed by F. Vercammen, Royal Zoological Society of Antwerp, Belgium J. Brandt, Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp Susceptible animal groups Cattle are the only susceptible animals. LSD has not been reported as a natural infection in wildlife. Giraffe and impala died after experimentally infection, whereas buffalo and gnu were refractory. Some suspected cases have been reported in wild animals in captivity (i.a. Oryx leucoryx) Causative organism The LSD virus belongs to the genus Capripoxvirus (family Poxviridae). It is a double-stranded DNA virus, which is closely related to the capripoxvirus, which causes sheep and goat pox. The virus is relatively heat stable, very resistant to cold, but not very resistant to light. Zoonotic potential The LSD virus is not infective to man. Distribution Currently, LSD is present in sub-Saharan Africa and Egypt. Transmission Transmission is mainly indirect through insects such as Stomoxys calcitrans and Musca confiscata The main vectors are still unknown. Direct transmission is also possible through saliva, milk, sperm, or through contact with lesions of infected animals. Incubation period The incubation period is 2 to 4 weeks. Clinical symptoms Fever, skin nodules (0.5 to 5 cm diameter) and swollen superficial lymph nodes are symptoms, which are present in most of the animals. -

An HRM Assay to Differentiate Sheeppox Virus Vaccine

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN An HRM Assay to Diferentiate Sheeppox Virus Vaccine Strains from Sheeppox Virus Field Isolates Received: 10 January 2019 Accepted: 15 April 2019 and other Capripoxvirus Species Published: xx xx xxxx Tesfaye Rufael Chibssa1,2,3, Tirumala Bharani K. Settypalli 1, Francisco J. Berguido1, Reingard Grabherr2, Angelika Loitsch4, Eeva Tuppurainen5, Nick Nwankpa6, Karim Tounkara6, Hafsa Madani7, Amel Omani7, Mariane Diop8, Giovanni Cattoli1, Adama Diallo8,9 & Charles Euloge Lamien 1 Sheep poxvirus (SPPV), goat poxvirus (GTPV) and lumpy skin disease virus (LSDV) afect small ruminants and cattle causing sheeppox (SPP), goatpox (GTP) and lumpy skin disease (LSD) respectively. In endemic areas, vaccination with live attenuated vaccines derived from SPPV, GTPV or LSDV provides protection from SPP and GTP. As live poxviruses may cause adverse reactions in vaccinated animals, it is imperative to develop new diagnostic tools for the diferentiation of SPPV feld strains from attenuated vaccine strains. Within the capripoxvirus (CaPV) homolog of the variola virus B22R gene, we identifed a unique region in SPPV vaccines with two deletions of 21 and 27 nucleotides and developed a High- Resolution Melting (HRM)-based assay. The HRM assay produces four distinct melting peaks, enabling the diferentiation between SPPV vaccines, SPPV feld isolates, GTPV and LSDV. This HRM assay is sensitive, specifc, and provides a cost-efective means for the detection and classifcation of CaPVs and the diferentiation of SPPV vaccines from SPPV feld isolates. Sheeppox (SPP), goatpox (GTP) and lumpy skin disease (LSD) are three important pox diseases of sheep, goat and cattle respectively1,2. Te responsible viruses, sheep poxvirus (SPPV), goat poxvirus (GTPV) and lumpy skin disease virus (LSDV) are large, complex, double-stranded DNA viruses of the genus Capripoxvirus, subfamily Chordopoxvirinae, family Poxviridae3. -

A Single Vertebrate DNA Virus Protein Disarms Invertebrate Immunity To

RESEARCH ARTICLE elifesciences.org A single vertebrate DNA virus protein disarms invertebrate immunity to RNA virus infection Don B Gammon1, Sophie Duraffour2, Daniel K Rozelle3, Heidi Hehnly4, Rita Sharma1,5, Michael E Sparks6†, Cara C West7, Ying Chen1, James J Moresco8, Graciela Andrei2, John H Connor3, Darryl Conte Jr.1, Dawn E Gundersen-Rindal6, William L Marshall7‡, John R Yates8, Neal Silverman7, Craig C Mello1,5* 1RNA Therapeutics Institute, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, United States; 2Rega Institute for Medical Research, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium; 3Department of Microbiology, Boston University, Boston, United States; 4Program in Molecular Medicine, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, United States; 5Howard Hughes Medical Institute, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, United States; 6Agricultural Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture, Beltsville, United States; 7Department of Medicine, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, United States; 8Department of Chemical Physiology, The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, United States *For correspondence: craig. [email protected] Abstract Virus-host interactions drive a remarkable diversity of immune responses and Present address: †Multidrug- countermeasures. We found that two RNA viruses with broad host ranges, vesicular stomatitis resistant Organism Repository virus (VSV) and Sindbis virus (SINV), are completely restricted in their replication after entry into and Surveillance Network, Walter Lepidopteran cells. This restriction is overcome when cells are co-infected with vaccinia virus Reed Army Institute of Research, (VACV), a vertebrate DNA virus. Using RNAi screening, we show that Lepidopteran RNAi, Nuclear Silver Spring, United States; Factor-κB, and ubiquitin-proteasome pathways restrict RNA virus infection. Surprisingly, a highly ‡Merck Research Laboratories, conserved, uncharacterized VACV protein, A51R, can partially overcome this virus restriction. -

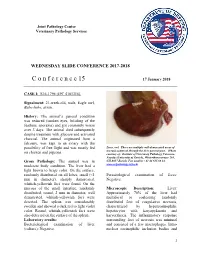

C O N F E R E N C E 15 17 January 2018

Joint Pathology Center Veterinary Pathology Services WEDNESDAY SLIDE CONFERENCE 2017-2018 C o n f e r e n c e 15 17 January 2018 CASE I: S16-1796 (JPC 4101316). Signalment: 21-week-old, male, Eagle owl, Bubo bubo, avian. History: The animal’s general condition was reduced (sunken eyes, bristling of the feathers, anorexia) and got constantly worse over 3 days. The animal died subsequently despite treatment with glucose and activated charcoal. The animal originated from a falconry, was kept in an aviary with the possibility of free flight and was mostly fed Liver, owl. There are multiple well-demarcated areas of necrosis scattered through the liver parenchyma. (Photo on chicken and pigeons. courtesy of: Institute of Veterinary Pathology Vetsuisse- Faculty (University of Zurich), Winterthurerstrasse 268, Gross Pathology: The animal was in CH-8057 Zurich, Fax number +41 44 635 89 34, moderate body condition. The liver had a www.vetpathology.uzh.ch) light brown to beige color. On the surface, randomly distributed on all lobes, small (<1 Parasitological examination of feces: mm in diameter), sharply demarcated, Negative. whitish-yellowish foci were found. On the mucosa of the small intestine, randomly Microscopic Description: Liver: distributed, round, 2 mm in diameter, well Approximately 70% of the liver had demarcated, whitish-yellowish foci were multifocal to coalescing randomly detected. The spleen was considerably distributed foci of coagulative necrosis, swollen and showed a dark red to light violet characterized by hypereosinophilic color. Round, whitish-yellowish foci were hepatocytes with karyopyknosis and also detected on the surface of the spleen. karyorrhexis. The inflammatory response Laboratory results: surrounding foci of necrosis was minimal Bacteriological examination of liver and consisted of a few macrophages. -

Viruses Status January 2013 FOEN/FOPH 2013 1

Classification of Organisms. Part 2: Viruses Status January 2013 FOEN/FOPH 2013 1 Authors: Prof. Dr. Riccardo Wittek, Dr. Karoline Dorsch-Häsler, Julia Link > Classification of Organisms Part 2: Viruses The classification of viruses was first published in 2005 and revised in 2010. Classification of Organisms. Part 2: Viruses Status January 2013 FOEN/FOPH 2013 2 Name Group Remarks Adenoviridae Aviadenovirus (Avian adenoviruses) Duck adenovirus 2 TEN Duck adenovirus 2 2 PM Fowl adenovirus A 2 Fowl adenovirus 1 (CELO, 112, Phelps) 2 PM Fowl adenovirus B 2 Fowl adenovirus 5 (340, TR22) 2 PM Fowl adenovirus C 2 Fowl adenovirus 10 (C-2B, M11, CFA20) 2 PM Fowl adenovirus 4 (KR-5, J-2) 2 PM Fowl adenovirus D 2 Fowl adenovirus 11 (380) 2 PM Fowl adenovirus 2 (GAL-1, 685, SR48) 2 PM Fowl adenovirus 3 (SR49, 75) 2 PM Fowl adenovirus 9 (A2, 90) 2 PM Fowl adenovirus E 2 Fowl adenovirus 6 (CR119, 168) 2 PM Fowl adenovirus 7 (YR36, X-11) 2 PM Fowl adenovirus 8a (TR59, T-8, CFA40) 2 PM Fowl adenovirus 8b (764, B3) 2 PM Goose adenovirus 2 Goose adenovirus 1-3 2 PM Pigeon adenovirus 2 PM TEN Turkey adenovirus 2 TEN Turkey adenovirus 1, 2 2 PM Mastadenovirus (Mammalian adenoviruses) Bovine adenovirus A 2 Bovine adenovirus 1 2 PM Bovine adenovirus B 2 Bovine adenovirus 3 2 PM Bovine adenovirus C 2 Bovine adenovirus 10 2 PM Canine adenovirus 2 Canine adenovirus 1,2 2 PM Caprine adenovirus 2 TEN Goat adenovirus 1, 2 2 PM Equine adenovirus A 2 Equine adenovirus 1 2 PM Equine adenovirus B 2 Equine adenovirus 2 2 PM Classification of Organisms.