Interview with Major General John L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

Howard Duff Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt8489r0cj No online items Finding Aid for the Howard Duff Collection Processed by UCLA Performing Arts Special Collections staff. UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections University of California, Los Angeles, Library Performing Arts Special Collections, Room A1713 Charles E. Young Research Library, Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Phone: (310) 825-4988 Fax: (310) 206-1864 Email: [email protected] http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm ©2007 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Howard Duff 282 1 Collection Descriptive Summary Title: Howard Duff Collection Collection number: 282 Creator: Duff, Howard Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Performing Arts Special Collections Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE: Advance notice required for access. Access Collection is open for research. Publication Rights Property rights in the physical objects belong to the UCLA Performing Arts Special Collections. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. It is the responsibility of the researcher to determine who holds the copyright and pursue the copyright owner or his or her heir for permission to publish if the Performing Arts Special Collectionsdoes not hold the copyright. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Howard Duff Collection, 282, Performing Arts Special Collections, University of California, Los Angeles. Biography Prolific character actor Howard Duff was born on November 24, 1913 in Bremerton, Washington and raised in Seattle. Duff's career spans the early days of radio when he played detective Sam Spade to his numerous roles in television, theater, and film. -

The Narrative Functions of Television Dreams by Cynthia A. Burkhead A

Dancing Dwarfs and Talking Fish: The Narrative Functions of Television Dreams By Cynthia A. Burkhead A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Ph.D. Department of English Middle Tennessee State University December, 2010 UMI Number: 3459290 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Dissertation Publishing UMI 3459290 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 DANCING DWARFS AND TALKING FISH: THE NARRATIVE FUNCTIONS OF TELEVISION DREAMS CYNTHIA BURKHEAD Approved: jr^QL^^lAo Qjrg/XA ^ Dr. David Lavery, Committee Chair c^&^^Ce~y Dr. Linda Badley, Reader A>& l-Lr 7i Dr./ Jill Hague, Rea J <7VM Dr. Tom Strawman, Chair, English Department Dr. Michael D. Allen, Dean, College of Graduate Studies DEDICATION First and foremost, I dedicate this work to my husband, John Burkhead, who lovingly carved for me the space and time that made this dissertation possible and then protected that space and time as fiercely as if it were his own. I dedicate this project also to my children, Joshua Scanlan, Daniel Scanlan, Stephen Burkhead, and Juliette Van Hoff, my son-in-law and daughter-in-law, and my grandchildren, Johnathan Burkhead and Olivia Van Hoff, who have all been so impressively patient during this process. -

New on Video &

New On Video & DVD Yes Man Jim Carrey returns to hilarious form with this romantic comedy in the same vein as the Carrey classic Liar Liar. After a few stints in more serious features like Eternal Sunshine Of The Spotless Mind and The Number 23, Carrey seems right at home playing Carl, a divorcé who starts out the film depressed and withdrawn, scared of taking a risk. Pressured by his best friend, Peter (Bradley Cooper), to get his act together or be stuck with a lonely life, Carl attends a New Age self-help seminar intended to change "no men" like Carl into "yes men" willing to meet life's challenges with gusto. Carl is reluctant at first, but finds the seminar to be ultimately life-changing when he's coerced into giving the "say yes" attitude a try. As the first opportunity to say yes presents itself, Carl hesitantly utters the three-letter word, setting the stage for a domino effect of good rewards, and giving Carrey a platform to show off his comic chops. But over time Carl realizes that saying yes to everything indiscriminately can reap results as complicated and messy as his life had become when saying "no" was his norm. The always-quirky Zooey Deschanel adds her signature charm as Carl's love interest, Allison. An unlikely match at first glance, the pair actually develop great chemistry as the story progresses, the actors play- ing off each other's different styles of humor. Rhys Darby also shines as Carl's loveable but clueless boss, and That 70s Show's Danny Masterson appears as another one of Carl's friends. -

El Fenix Will Reopen, Still a Family Business

2A| WEDNESDAY, MAY 12, 2021| ABILENE REPORTER-NEWS El Fenix will reopen, still a family business Greg Jaklewicz and cleaning are under way. An application for a liquor family business. But not much since college. Abilene Reporter-News license has been turned in. She said she is learning her mom’s recipes and USA TODAY NETWORK – TEXAS The couple have lived on Kaua‘i, where Luisa promises to keep favorite menu items in front of cus- worked for eight years with contracting and procure- tomers. El Fenix, the landmark Abilene Mexican restaurant, ment for Pacific Missile Range Facility. Before that, she “It will be hard to live up to my mother ... but we will reopen this summer. was employed at art galleries, she said. want to keep everything the way it was, the same reci- After 83 years in business, El Fenix closed Christ- For the past two years, she has been a stay-at-home pes,” she said, laughing. “We both are learning it all. mas Eve. However, owner Olivia Velez had hoped mom. The couple’s second child, a daughter named Ei- It’s brand new for the both of us. someone, perhaps in the family, would step up. ly Olivia, was born Dec. 23 - the day before El Fenix “But I have mom’s guidance.” Luisa Velez-McKamey did. closed. The reality of the restaurant closing pushed the And she just didn’t step in, she flew in. “We couldn’t be there for that,” Velez-McKamey couple toward a decision to trade the Hawaiian island After living for the past 14 years in Hawaii, she and said of the closing, which made her sad. -

COA Template

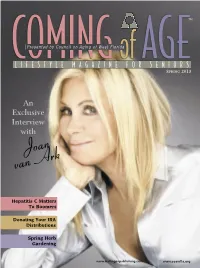

TM COMINGPresented by Council on Aging of West Floridaof AGE LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE FOR SENIORS SPRING 2013 An Exclusive Interview with Joan van Ark Hepatitis C Matters To Boomers Donating Your IRA Distributions Spring Herb Gardening www.ballingerpublishing.com www.coawfla.org COMMUNICATIONS CORNER Jeff Nall, APR, CPRC Editor-in-Chief The groundhog did not see his shadow and we’ve “sprung our clocks forward,” so now it is time to get out and enjoy the many outdoor activities that our area has to offer. Some of my favorites are the free outdoor concerts such as JazzFest, Christopher’s Concerts and Bands on the Beach. I tend to run into many of our readers at these events, but if you haven’t been, check out page 40. For another outdoor option for those with more of a green thumb, check out our article on page 15, which has useful tips for planting an herb garden. This issue also contains important information for baby boomers about Readers’ Services hepatitis C. According to the Centers for Disease Control, people born from Subscriptions Your subscription to Coming of Age 1945 through 1965 account for more than 75 percent of American adults comes automatically with your living with the disease and most do not know they have it. In terms of membership to Council on Aging of financial health, our finance article on page 18 explains how qualified West Florida. If you have questions about your subscription, call Jeff charitable distributions (QCDs) from Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs) Nall at (850) 432-1475 ext. 130 or are attractive to some investors because QCDs can be used to satisfy required email [email protected]. -

The United States and the Greek Coup of 1967

Were the Eagle and the Phoenix Birds of a Feather? The United States and the Greek Coup of 1967 by Louis Klarevas Assistant Professor of Political Science City University of New York—College of Staten Island & Associate Fellow Hellenic Observatory—London School of Economics Discussion Paper No. 15 Hellenic Observatory-European Institute London School of Economics Houghton Street London WC2A 2AE http://www.lse.ac.uk/collections/hellenicObservatory February 2004 Author’s Note: The author wishes to thank the Hellenic Observatory of the London School of Economics for its generous support in the undertaking of this project. The author also wishes to thank Kevin Featherstone, Spyros Economides, and Dimitrios Triantaphyllou for comments on a previous draft. In the summer of 2004, Greece will host the Olympic Games. Americans attending the games and visiting traditional tourist stops in Athens are sure to be greeted with open arms. But for those who delve a bit further into the country-side seeking a taste of average Greek life, some are sure to hear some fascinating tales flavored with a strong hint of anti-Americanism. To many foreigners that visit Greece these days, it might seem like the cradle of democracy is also the cradle of conspiracy. Take these schemes, for example: (1) Orthodox Serbs, not Muslims, were the true victims of the slaughters in the Balkans during the 1990s—and the primary reason that NATO intervened was so that the United States could establish a military foothold there;1 (2) the U.S. Ambassador played a tacit role in the removal of the Secretary- General of Greece’s ruling political party;2 and (3) the attack on the World Trade Center was a joint Jewish-American conspiracy to justify a Western war against Muslims—with reports that no Jews died in the September 11 attacks.3 All of these perspectives have numerous subscribers in Greece. -

Pakistanis Fault US-Backed Regime

Workers and oppressed peoples of the world unite! JAN. 10, 2008 VOL. 50, NO. 1 50¢ Rebellions follow Bhutto assassination • FreshDirect • Bolivia 12 Pakistanis fault U.S.-backed regime By Deirdre Griswold of elected civilian government between coups. Bhutto’s father held the post of prime minister during one of them; he was over- The crisis in Pakistan has entered a new and even more acute thrown by the military and later hanged. Benazir Bhutto served phase with the assassination of Benazir Bhutto, head of the twice as prime minister—from 1988-1990 and 1993-1996, when Pakistan Peoples Party, who had returned from exile just two she was forced out of office, then charged with corruption and WWW.WECHARGEGENOCIDE.COM months earlier. She was killed on Dec. 27 while driving through sent into exile. a large welcoming crowd in Rawalpindi following a political General Musharraf, the latest in a string of military dictators, ETHNIC rally. seized power in a coup in 1999 but later reinvented his rule by REMOVAL? The regimes of both Gen. Pervez Musharraf in Islamabad and creating a political party and winning the presidency in an elec- George W. Bush in Washington rushed to blame the brutal mur- tion widely regarded as rigged. During these eight years, the Battle for New Orleans 3 der on Islamic militants. poverty of the masses has deepened while much of the country’s Their pronouncements failed to convince the public. Even wealth has gone to the military elite. Musharraf himself has sur- the major imperialist newspapers in the U.S. -

Joan Van Ark

Joan van Ark Tony nominee Joan van Ark’s most recent television role was in the movie “The Wedding Stalker” airing on Lifetime with “Glee”s Heather Morris. She is best known for her role as Valene Ewing on television’s iconic Dallas and Knots Landing for 14 years. She earned her Tony nomination for her Broadway role in The School for Wives and won Broadway’s Theater World Award for The Rules of the Game. In 2005 she appeared at the Kennedy Center in the world première of Tennessee Williams’ Five by Tenn as part of the Center’s Williams celebration with Sally Field, Patricia Clarkson and Kathleen Chalfant. She co-starred in the Feydeau farce Private Fittings at the La Jolla Playhouse, the New York theatre production of The Exonerated as well as the West Coast production of the off Broadway hit Vagina Monologues by award-winning playwright Eve Ensler. Her most recent theater appearance was in Tennessee Williams’ A Lovely Sunday for Creve Coeur at Hartford Stage directed by Michael Wilson. She also appeared off- Broadway in Love Letters and co-starred in the New York production of Edward Albee’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play Three Tall Women. Her Los Angeles theater credits include Cyrano de Bergerac, playing Roxanne opposite Richard Chamberlain’s Cyrano, Ring Around the Moon with Michael York, Chemin de Fer, Heartbreak House and As You Like It, for which she won a Los Angeles Drama Critics Award. She starred as Lady Macbeth in the Grove Shakespeare Festival’s production of Macbeth. She also appeared at The Shakespeare Theatre in Washington, D.C. -

Dallas Season 4 Episode Guide

Dallas season 4 episode guide click here to download Alan Beam is brought back to Dallas by the police. Cliff is taken into custody when a fired gun is found in his apartment. Marilee Stone No. of episodes: Season 8: Dallas: Season 8 Trailer The most successful prime-time soap in TV history, `Dallas' spawned the popular `Knots Season 4 Episode Guide. Season Four (Please note these are the original series Episode seasons. For the DVD release is termed Seson 5). Missing Heir.Missing Heir · The Sweet Smell of Revenge · The Big Shut Down · The Phoenix. Dallas Season Finale TVLINE | I know your plan is to jump six months ahead in Season 4. Oh, it's going to be revealed in the first episode. Dallas season 4 episode guide on www.doorway.ru Watch all 23 Dallas episodes from season 4,view pictures, get episode information and more. Watch Dallas episodes, get episode information, recaps and more. 4/24/ Dallas: War of the Ewings" begins with a scene of Bobby Ewing in the shower. the long-running series, which ended in , J.R. returns to Dallas, hoping to. Drama · The next generation of the Ewing family - cousins John Ross Ewing and Christopher Dallas. 42min | Drama, Romance | TV Series (–) · Episode Guide. 40 episodes · Dallas Poster · Trailer. | Trailer. 5 VIDEOS | IMAGES. The first season of Dallas (originally promoted as the miniseries) lasted for five episodes Previous season: N/A-None; Next season: Season 2 episode guide 4, "Winds of Vengeance", Camille Marchetta, Irving J. Moore, April 23, , 4. Season 1, Episode 1 – Aired: 4/2/ Digger's Daughter Bobby's marriage to Pamela, the daughter of his father's sworn enemy, Digger. -

Bath County High School Daily Announcements

Bath County High School Thursday Daily Announcements November 21, 2013 Attendance –% - not available Turkey, dressing, mashed potatoes, gravy, green beans, rolls, pecan or pumpkin pie, cranberry sauce, fruit, milk The 25th annual Tim's Toy Trot for Tots will be held on Saturday, December, 0 7, 2013, beginning at 5:00 a.m. In rain, snow or sleet, the runners (Tim Bailey, Shawn Tolle & BCHS Drama class will be performing Dec. 19th at 1:30 here in our gym and again Dec. 20th at 7 pm for the community. The play, 'Blended' was additional volunteers along the way ) will begin their 52 mile written by Mrs. Blount and includes singing dancing and several special trek via US 60 (Fayette County Courthouse to Bath County solos by this year’s students. The cost of admission is $3 for adults and 1$ for students, all children under 5 are free. This is the first year for our Courthouse) which is expected to take approximately 12 hours Drama class and we hope to grow our program; so, come on out and to complete. show your support. This event is designed to help families that are struggling, have an enjoyable Christmas. The holiday is brighter when watching a child’s joy as they hurry to find the goodies Santa has left for them... and that is what we want to do with your help... allow children to experience the blessings and joys of Christmas. In the past 24 years, Tim's Toy Trot for Tots campaign has been a great success - this one is expected to be no different. -

CELEBRITIES SCHEDULED to ATTEND (Appearance of Celebrities Subject to Change)

Festival of Arts / Pageant of the Masters Celebrity Benefit Event August 26, 2017 CELEBRITIES SCHEDULED TO ATTEND (Appearance of Celebrities Subject to Change) Bryan Cranston (Host) – Cranston is an Academy Award nominee, a four time Emmy Award winner, and a Golden Globe, SAG, and Tony Award winner. He starred in AMC’s hit series BREAKING BAD and won a Golden Globe and Emmy award for his portrayal of “Walter White.” He also appeared in the FOX series MALCOLM IN THE MIDDLE as “Hal.” Recent film credits include leading roles in TRUMBO, GET A JOB, ALL THE WAY, WHY HIM?, THE INFILTRATOR and WAKEFIELD. Cranston is currently in production on UNTOUCHABLE with Kevin Hart, and recently wrapped production on LAST FLAG FLYING with Steve Carell and Laurence Fishburne. Herb Alpert (Performer) – A legendary trumpet player, Alpert’s extraordinary musicianship has earned him five #1 hits, nine Grammy Awards, the latest from his 2014 album, “Steppin’ Out,” fifteen Gold albums, fourteen Platinum albums and has sold over 72 million records. Herb Alpert & The Tijuana Brass propelled his sound into the pop music limelight, at one point outselling the Beatles two to one. In 1966, they achieved the since-unmatched feat of simultaneously having four albums in the Top 10 and five in the Top 20. Herb Alpert also has the distinction of being the only artist who has had a #1 instrumental and vocal single. Lani Hall (Performer) – Grammy Award-winning vocalist and producer, Hall started her singing career in 1966, as the lead singer of Sergio Mendes’ break through group, Brasil ’66.