A Cold War Crusader on an Ideological Battlefield: Andrew Eiva, the KGB, and the Soviet-Afghan War Although He Was Only Five Ye

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Brezhnev Era (1964–1982)

Name _______________________________________________ Date _____________ The Brezhnev Era (1964–1982) Next to Stalin, Leonid Brezhnev ruled the Soviet Union longer than any other leader. Brezhnev and his supporters stressed the ties with the Stalinist era by focusing on his good points and ignoring his crimes. 1. What is the KGB? Brezhnev strengthened the Soviet bureaucracy as well What was its as the KGB (Committee of State Security)—formed in purpose? (list 2) 1954; its mission was to defend the Soviet government from its enemies at home and abroad. The KGB suppressed dissidents who spoke out against the government at home and in the satellite countries. The Soviets also invested in a large military buildup and were determined to never again suffer a humiliating defeat, as happened in the Cuban Missile Crisis. Yet Brezhnev proceeded cautiously in the mid-1960s and sought to avoid confrontation with the West. He was determined, however, to protect Soviet interests. Brezhnev Doctrine (1968) 2. What was the Prague In 1968, Alexander Dubček (1921–1992) became head of the Czechoslovakia Spring? Communist Party and began a series of reforms known as the Prague Spring reforms, which sought to make communism more humanistic. He lifted censorship, permitted non-communists to form political groups, and wanted to trade with the West, but still remain true to communist ideals. Brezhnev viewed these reforms as a capitalistic threat to the socialist ideologies of communism and, in August of 1968, sent over 500,000 Soviet and Eastern European troops 3. How did Brezhnev to occupy Czechoslovakia. In the Brezhnev Doctrine, he defended the Soviet react to the Prague military invasion of Czechoslovakia, saying in effect, that antisocialist elements Spring? in a single socialist country can compromise the entire socialist system, and thus other socialist countries have the right to intervene militarily if they see the need to do so. -

Afghanistan, 1989-1996: Between the Soviets and the Taliban

Afghanistan, 1989-1996: Between the Soviets and the Taliban A thesis submitted to the Miami University Honors Program in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for University Honors with Distinction by, Brandon Smith May 2005 Oxford, OH ABSTRACT AFGHANISTAN, 1989-1996: BETWEEN THE SOVIETS AND THE TALIBAN by, BRANDON SMITH This paper examines why the Afghan resistance fighters from the war against the Soviets, the mujahideen, were unable to establish a government in the time period between the withdrawal of the Soviet army from Afghanistan in 1989 and the consolidation of power by the Taliban in 1996. A number of conflicting explanations exist regarding Afghanistan’s instability during this time period. This paper argues that the developments in Afghanistan from 1989 to 1996 can be linked to the influence of actors outside Afghanistan, but not to the extent that the choices and actions of individual actors can be overlooked or ignored. Further, the choices and actions of individual actors need not be explained in terms of ancient animosities or historic tendencies, but rather were calculated moves to secure power. In support of this argument, international, national, and individual level factors are examined. ii Afghanistan, 1989-1996: Between the Soviets and the Taliban by, Brandon Smith Approved by: _________________________, Advisor Karen L. Dawisha _________________________, Reader John M. Rothgeb, Jr. _________________________, Reader Homayun Sidky Accepted by: ________________________, Director, University Honors Program iii Thanks to Karen Dawisha for her guidance and willingness to help on her year off, and to John Rothgeb and Homayun Sidky for taking the time to read the final draft and offer their feedback. -

COIN in Afghanistan - Winning the Battles, Losing the War?

COIN in Afghanistan - Winning the Battles, Losing the War? MAGNUS NORELL FOI, Swedish Defence Research Agency, is a mainly assignment-funded agency under the Ministry of Defence. The core activities are research, method and technology development, as well as studies conducted in the interests of Swedish defence and the safety and security of society. The organisation employs approximately 1000 personnel of whom about 800 are scientists. This makes FOI Sweden’s largest research institute. FOI gives its customers access to leading-edge expertise in a large number of fields such as security policy studies, defence and security related analyses, the assessment of various types of threat, systems for control and management of crises, protection against and management of hazardous substances, IT security and the potential offered by new sensors. FOI Swedish Defence Research Agency Phone: +46 8 555 030 00 www.foi.se FOI Memo 3123 Memo Defence Analysis Defence Analysis Fax: +46 8 555 031 00 ISSN 1650-1942 March 2010 SE-164 90 Stockholm Magnus Norell COIN in Afghanistan - Winning the Battles, Losing the War? “If you don’t know where you’re going. Any road will take you there” (From a song by George Harrison) FOI Memo 3123 Title COIN in Afghanistan – Winning the Battles, Losing the War? Rapportnr/Report no FOI Memo 3123 Rapporttyp/Report Type FOI Memo Månad/Month Mars/March Utgivningsår/Year 2010 Antal sidor/Pages 41 p ISSN ISSN 1650-1942 Kund/Customer Försvarsdepartementet Projektnr/Project no A12004 Godkänd av/Approved by Eva Mittermaier FOI, Totalförsvarets Forskningsinstitut FOI, Swedish Defence Research Agency Avdelningen för Försvarsanalys Department of Defence Analysis 164 90 Stockholm SE-164 90 Stockholm FOI Memo 3123 Programme managers remarks The Asia Security Studies programme at the Swedish Defence Research Agency’s Department of Defence Analysis conducts research and policy relevant analysis on defence and security related issues. -

Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference by Fletcher Schoen and Christopher J

STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 11 Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference by Fletcher Schoen and Christopher J. Lamb Center for Strategic Research Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is National Defense University’s (NDU’s) dedicated research arm. INSS includes the Center for Strategic Research, Center for Complex Operations, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, Center for Technology and National Security Policy, Center for Transatlantic Security Studies, and Conflict Records Research Center. The military and civilian analysts and staff who comprise INSS and its subcomponents execute their mission by conducting research and analysis, publishing, and participating in conferences, policy support, and outreach. The mission of INSS is to conduct strategic studies for the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Unified Combatant Commands in support of the academic programs at NDU and to perform outreach to other U.S. Government agencies and the broader national security community. Cover: Kathleen Bailey presents evidence of forgeries to the press corps. Credit: The Washington Times Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference By Fletcher Schoen and Christopher J. Lamb Institute for National Strategic Studies Strategic Perspectives, No. 11 Series Editor: Nicholas Rostow National Defense University Press Washington, D.C. June 2012 Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Defense Department or any other agency of the Federal Government. -

The Cold War and Mccarthyism Howard Tennant

WARS The Cold War and McCarthyism Howard Tennant 1. Work in pairs. Read the text on the Cold War and then make questions, HISTORY using the phrases in bold. The first question has been done for you. Text A The Cold War The term ‘Cold War’ is used to describe the relationship between America and the Soviet Union from 1945 to 1980. It was a period of conflict, tension and rivalry between the world’s two superpowers. (1) Neither side fought the other – the consequences would be too terrible – but they did fight for their beliefs using other countries. For example, in (2) the Vietnam war in the 1960s and 1970s, (3) South Vietnam was against the Communists and supported by America. North Vietnam was pro-Communist and fought the south (4) using weapons from communist Russia or communist China. In Afghanistan, the Americans supplied the Afghans with weapons after (5) the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in 1979. They never physically involved themselves and so avoided direct conflict with the Soviet Union. 1. Did America and the Soviet Union fight each other? 2. When was ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________? 3. Which country did the USA ____________________________________________________________________? 4. Which countries supplied weapons ______________________________________________________________? 5. When did the Soviet Union ______________________________________________________________________? • This page has been downloaded from www.onestopclil.com. 1 of 2 Written by Howard Tennant. © Copyright Macmillan Publishers Ltd 2008. FROM WEBSITE •PHOTOCOPIABLECAN BE DOWNLOADED HISTORY 2. In pairs read this text on McCarthyism and make the questions. Text B McCarthyism (1) The term ‘McCarthyism’ refers to a period of strong anti-communist suspicion in the USA that lasted from the late 1940s to the late 1950s. -

KGB Spy War with U.S. Falls Victim to Glasnost Soviet Intelligence Ief to Revamp Agency Atm C4 �Ttifve,L

KGB Spy War With U.S. Falls Victim to Glasnost Soviet Intelligence ief to Revamp Agency Atm c4 ttifve,L. *By Michael dobbs Washington Post Foreign Service MOSCOW, Oct. 2—Abandoning the shadowy anonymity favored by his predecessors, the Kremlin's new spymaster declared an end to- day to the secret intelligence war with the United States and prom- ised to put a stop to the practice of sending Soviet agents abroad under journalistic cover. Yevgeny Primakov, who was nominated as the Soviet Union's top spy two days ago by President Mikhail Gorbachev, told a news conference that he was in favor of greater glasnost, or openness, in the intelligence business. He said that his agency would follow the example of the U.S. CIA by making YEVGENY PRIMAKOV some of its information available to ... "we must use analytical methods" scholars and businessmen in addi- tion to the government. "If you think that spies are people into a professional intelligence- in gray coats, skulking around gathering organization along the street corners, listening to people's lines of the CIA. His appointment conversations and wielding iron comes at a time when both the KGB bars, then my appointment is un, and its foreign intelligence arm are natural," said Primakov, 61, a for- in the throes of major internal up- mer journalist and academic who heavals following August's abortive served as Gorbachev's chief diplo- coup by hard-line Communists. matic trouble-shooter. "We must The First Chief Directorate, as use analytical methods, synthesize the foreign intelligence service has information. -

You, Me, and Charlie Wilson's War George Crile's Charlie Wilson's War, the Tale of the Defeat of the Soviet

SPECIAL SECTION: You, Me, and Charlie Wilson's War George Crile's Charlie Wilson's War, the tale of the defeat of the Soviet Union in Afghanistan (which led directly to its subsequent unraveling), is quite simply the most extraordinary non- fiction potboiler I have ever read. And, perhaps surprisingly, it has lessons for you and me from Congressman Wilson and his CIA cohort, Gust Avrakotos: (1) Make friends with the ... "Invisible 95%." Gust Avrakotos apparently knew every "top floor" CIA executive secretary by name—and had helped many of them sort out personal or professional problems. The folks in the mailroom and in the bowels of the computer operations affairs were also the subject of Gust's intense and affectionate attentions. In effect, you could say that Gust was Commander-in-Chief of the "Invisible 95%" of the Agency—which allowed him to make extraordinary things happen despite furious resistance from his bosses and bosses' bosses sitting atop a very rigid organization. (2) Create a Networker-Doer Partnership. Congressman Wilson had the networking part down, but he needed help with the doing. Conversely, if you are the doer, then you must find the politician-networker. (3) Carefully manage the BOF/Balance Of Favors. Practice potlatch—giving so much help to so many people on so many occasions (purposeful overkill!) that there is little issue about their supporting you when the (rare!) time comes to call in the chits. (4) Follow the money! "Anybody with a brain can figure out that if they can get on the Defense subcommittee, that's where they ought to be—because that's where the money is."—Charlie Wilson (5) Found material. -

CIA Files Relating to Heinz Felfe, SS Officer and KGB Spy

CIA Files Relating to Heinz Felfe, SS officer and KGB Spy Norman J. W. Goda Ohio University Heinz Felfe was an officer in Hitler’s SS who after World War II became a KGB penetration agent, infiltrating West German intelligence for an entire decade. He was arrested by the West German authorities in 1961 and tried in 1963 whereupon the broad outlines of his case became public knowledge. Years after his 1969 release to East Germany (in exchange for three West German spies) Felfe also wrote memoirs and in the 1980s, CIA officers involved with the case granted interviews to author Mary Ellen Reese.1 In accordance with the Nazi War Crimes Disclosure Act the CIA has released significant formerly classified material on Felfe, including a massive “Name File” consisting of 1,900 pages; a CIA Damage Assessment of the Felfe case completed in 1963; and a 1969 study of Felfe as an example of a successful KGB penetration agent.2 These files represent the first release of official documents concerning the Felfe case, forty-five years after his arrest. The materials are of great historical significance and add detail to the Felfe case in the following ways: • They show in more detail than ever before how Soviet and Western intelligence alike used former Nazi SS officers during the Cold War years. 1 Heinz Felfe, Im Dienst des Gegners: 10 Jahre Moskaus Mann im BND (Hamburg: Rasch & Röhring, 1986); Mary Ellen Reese, General Reinhard Gehlen: The CIA Connection (Fairfax, VA: George Mason University Press, 1990), pp. 143-71. 2 Name File Felfe, Heinz, 4 vols., National Archives and Records Administration [NARA], Record Group [RG] 263 (Records of the Central Intelligence Agency), CIA Name Files, Second Release, Boxes 22-23; “Felfe, Heinz: Damage Assessment, NARA, RG 263, CIA Subject Files, Second Release, Box 1; “KGB Exploitation of Heinz Felfe: Successful KGB Penetration of a Western Intelligence Service,” March 1969, NARA, RG 263, CIA Subject Files, Second Release, Box 1. -

2 the Reform of the Warsaw Pact

Research Collection Working Paper Learning from the enemy NATO as a model for the Warsaw Pact Author(s): Mastny, Vojtech Publication Date: 2001 Permanent Link: https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-a-004148840 Rights / License: In Copyright - Non-Commercial Use Permitted This page was generated automatically upon download from the ETH Zurich Research Collection. For more information please consult the Terms of use. ETH Library Zürcher Beiträge zur Sicherheitspolitik und Konfliktforschung Nr.58 Vojtech Mastny Learning from the Enemy NATO as a Model for the Warsaw Pact Hrsg.: Kurt R. Spillmann und Andreas Wenger Forschungsstelle für Sicherheitspolitik und Konfliktanalyse der ETH Zürich CONTENTS Preface 5 Introduction 7 1 The Creation of the Warsaw Pact (1955-65) 9 2The Reform of the Warsaw Pact (1966-69) 19 3 The Demise of the Warsaw Pact (1969-91) 33 Conclusions 43 Abbreviations 45 Bibliography 47 coordinator of the Parallel History Project on NATO and the Warsaw PREFACE Pact (PHP), closely connected with the Center for Security Studies and Conflict Research (CSS) at the ETH Zürich. The CSS launched the PHP in 1999 together with the National Security Archive and the Cold War International History Project in Washington, DC, and the Institute of Military History, in Vienna. In 1955, the Warsaw Pact was created as a mirror image of NATO that could be negotiated away if favorable international conditions allowed Even though the Cold War is over, most military documents from this the Soviet Union to benefit from a simultaneous dissolution of both period are still being withheld for alleged or real security reasons. -

The Kgb in Afghanistan

THE KGB IN AFGHANISTAN RALPH PICKARD Figure 1: A display case of a KGB officer’s grouping showing his known Soviet and Afghanistan medals and award booklets earned during his service in the KGB. There has been much written over the years about the intent of stabilizing the Afghan government from the history of the Soviet forces occupation of Afghanistan deterioration that was occurring throughout the region and during the Cold War. However, less has been written especially the souring relationship with the government from the collecting community perspective about the prior to December 1979. The Soviet forces’ intent was Afghanistan medals and award booklets that were earned to seize all important Afghan government facilities and by Soviet personnel during that same time period. The other important areas.1 Within days after the Soviet forces intent of this article is to shed a little light on a few of invasion into Afghanistan and occupation of the capital the Afghanistan medals that were awarded during the of Kabul, the Afghanistan President was assassinated Cold War through a unique group that belonged to a and replaced with the more pro-Soviet government of KGB officer (Figure 1). This grouping provides strong President, Babrak Karmal, who had promised his loyalty indications that this officer served multiple tours and earlier to the Soviet government. 2,3,4 continued to operate in Afghanistan even after February 1989. However, prior to illustrating more about the group Prior to the invasion of Afghanistan by the Soviets the in this article, a brief overview of the Soviet invasion and two governments had an ongoing relationship dating back available history of the KGB in Afghanistan during the to the early 1920s with Soviet advisors and technicians Cold War will be presented. -

Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Intelligence

Russia • Military / Security Historical Dictionaries of Intelligence and Counterintelligence, No. 5 PRINGLE At its peak, the KGB (Komitet Gosudarstvennoy Bezopasnosti) was the largest HISTORICAL secret police and espionage organization in the world. It became so influential DICTIONARY OF in Soviet politics that several of its directors moved on to become premiers of the Soviet Union. In fact, Russian president Vladimir V. Putin is a former head of the KGB. The GRU (Glavnoe Razvedvitelnoe Upravleniye) is the principal intelligence unit of the Russian armed forces, having been established in 1920 by Leon Trotsky during the Russian civil war. It was the first subordinate to the KGB, and although the KGB broke up with the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the GRU remains intact, cohesive, highly efficient, and with far greater resources than its civilian counterparts. & The KGB and GRU are just two of the many Russian and Soviet intelli- gence agencies covered in Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Intelligence. Through a list of acronyms and abbreviations, a chronology, an introductory HISTORICAL DICTIONARY OF essay, a bibliography, and hundreds of cross-referenced dictionary entries, a clear picture of this subject is presented. Entries also cover Russian and Soviet leaders, leading intelligence and security officers, the Lenin and Stalin purges, the gulag, and noted espionage cases. INTELLIGENCE Robert W. Pringle is a former foreign service officer and intelligence analyst RUSSIAN with a lifelong interest in Russian security. He has served as a diplomat and intelligence professional in Africa, the former Soviet Union, and Eastern Europe. For orders and information please contact the publisher && SOVIET Scarecrow Press, Inc. -

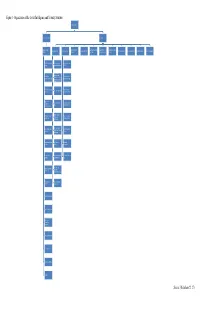

Organization of the Soviet Intelligence and Security Structure Source

Figure 1- Organization of the Soviet Intelligence and Security Structure General Chairman First Deputy Chairman Chief, GRU Deputy Chairman Space Intelligence Operational/ Technical Administrative/ Directorate for Foreign First Deputy Chief Chief of Information Personnel Directorate Political Department Financial Department Eighth Department Archives Department (KGB) Directorate Directorate Technical Directorate Relations First Chief Directorate First Directorate: Seventh Directorate: (Foreign) Europe and Morocco NATO Second Directorate: North and South Second Chief Eighth Directorate: America, Australia, Directorate (Internal) Individual Countries New Zealand, United Kingdom Fifth Chief Directorate Ninth Directorate: Third Directorate: Asia (Dissidents) Military Technology Eighth Chief Fourth Directorate: Tenth Directorate: Directorate Africa Military Economics (Communications) Fifth Directorate: Chief Border Troops Eleventh Directorate: Operational Directorates Doctrine, Weapons Intelligence Sixth Directorate: Third (Armed Forces) Twelfth Directorate: Radio, Radio-Technical Directorate Unknown Intelligence Seventh (Surveillance) First Direction: Institute of Directorate Moscow Information Ninth (Guards) Second Direction: East Information Command Directorate and West Berlin Post Third: National Technical Operations Liberation Directorate Movements, Terrorism Administration Fourth: Operations Directorate from Cuba Personnel Directorate Special Investigations Collation of Operational Experience State Communications Physical Security Registry and Archives Finance Source: (Richelson 22, 27) Figure 2- Organization of the United States Intelligence Community President National Security Advisor National Security DNI State DOD DOJ DHS DOE Treasury Commerce Council Nuclear CIO INR USDI FBI Intelligence Foreign $$ Flow Attachés Weapons Plans DIA NSA NGA NRO Military Services NSB Coast Guard Collection MSIC NGIC (Army) MRSIC (Air Analysis AFMic Force) NCTC J-2's ONI (Navy) CIA Main DIA INSCOM (Army) NCDC MIA (Marine) MIT Source: (Martin-McCormick) .