A Brief Summary of Conclusions There Is No Disputing the Fact That Few

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Unidad Latina, Lambda Upsilon Lambda Fraternity, Inc

La Unidad Latina, Lambda Upsilon Lambda Fraternity, Inc. Alpha Xi Chapter- Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana Foreword Below are the standard operating procedures by which the Iota Chapter of La Unidad Latina, Lambda Upsilon Lambda Fraternity, Incorporated shall abide. These procedures shall be used along with the Chapter Management Manual, National Constitution, Hermano Protocol, Caballero Protocol, National Pledge Manual, and university policies and procedures as the means of operating the chapter. The responsibilities and obligations provided are the minimum for chapter operation. All other obligations discussed, appointed, or committed to, throughout the year, are also binding. Executive Officer Obligations I. President The President shall be responsible for, but not limited to, coordinating and ensuring the following: 1. Providing a detailed report at all chapter meetings. 2. Implementation of all Iota Chapter annual programs. ( SEE APPENDIX A ) 3. Being the primary contact of communication between the National Council, the Office of Fraternity and Sorority Affairs, etc. 4. Completion and submission of the OFSA Annual Report. ( SEE APPENDIX Q ) 5. Reviewing the annual report requirements at the beginning of his term and ensuring that the chapter meets ALL CRITERIA for ALL eight sections including ALL awards criteria. 6. Creating and Submitting OR delegating, all awards applications for qualifying Hermanos and events, for recognition in the Greek Awards and Latino Student Council Awards. 7. Submitting a completed semester packet and compliance report to the National Council. 8. Create the agenda or each chapter meeting 9. The success of all chapter events. 10. Chapter Contracts Signed by all undergraduates. (Executive Board Obligations Contracts, Financial Dues Agreement) 11. -

International Standard

IEC 62106 ® Edition 2.0 2009-07 INTERNATIONAL STANDARD Specification of the Radio Data System (RDS) for VHF/FM sound broadcasting in the frequency range from 87,5 MHz to 108,0 MHz --`,,```,,,,````-`-`,,`,,`,`,,`--- IEC 62106:2009(E) Copyright International Electrotechnical Commission Provided by IHS under license with IEC No reproduction or networking permitted without license from IHS Not for Resale THIS PUBLICATION IS COPYRIGHT PROTECTED Copyright © 2009 IEC, Geneva, Switzerland All rights reserved. Unless otherwise specified, no part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and microfilm, without permission in writing from either IEC or IEC's member National Committee in the country of the requester. If you have any questions about IEC copyright or have an enquiry about obtaining additional rights to this publication, please contact the address below or your local IEC member National Committee for further information. IEC Central Office 3, rue de Varembé CH-1211 Geneva 20 Switzerland Email: [email protected] Web: www.iec.ch About the IEC The International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) is the leading global organization that prepares and publishes International Standards for all electrical, electronic and related technologies. About IEC publications The technical content of IEC publications is kept under constant review by the IEC. Please make sure that you have the latest edition, a corrigenda or an amendment might have been published. Catalogue of IEC publications: www.iec.ch/searchpub The IEC on-line Catalogue enables you to search by a variety of criteria (reference number, text, technical committee,…). -

Gamma Theta Upsilon - Zeta Chi Chapter

Geography Honor Society Gamma Theta Upsilon - Zeta Chi Chapter Gamma Theta Upsilon (GTU) is an international honor society in geography. Gamma Theta Upsilon was founded in 1928 and became a national organization in 1931. Members of GTU have met academic requirements and share a background and interest in geography. GTU chapter activities support geography knowledge and awareness. Eligibility for Regular Membership Initiates must: have completed a minimum of 3 geography courses, have a GPA of at least 3.3 (on a 4.0 scale) in geography courses, have completed at least 3 semesters or 5 quarters of full-time college course work. Note: Regular members do not have to be currently enrolled, nor must they be geography majors Why should you join GTU? GTU membership is earned through superior scholarship; it is an honor, and a professional distinction Members receive a handsome certificate, suitable for framing No further membership dues are paid to the national organization after the initiation fee Many members choose to remain active in GTU after graduation, by joining Omega Omega, the Alumni Chapter of GTU. The Purposes of GTU are to: Further professional interests in Geography by affording a common organization for those interested in the field Strengthen student and professional training through academic experiences in addition to those of the classroom and laboratory Advance the status of Geography as a cultural and practical discipline for study and investigation Encourage student research of high quality, and to promote an outlet for publication Create and administer funds for furthering graduate study and/or research in the field of Geography. -

The Use of Gamma in Place of Digamma in Ancient Greek

Mnemosyne (2020) 1-22 brill.com/mnem The Use of Gamma in Place of Digamma in Ancient Greek Francesco Camagni University of Manchester, UK [email protected] Received August 2019 | Accepted March 2020 Abstract Originally, Ancient Greek employed the letter digamma ( ϝ) to represent the /w/ sound. Over time, this sound disappeared, alongside the digamma that denoted it. However, to transcribe those archaic, dialectal, or foreign words that still retained this sound, lexicographers employed other letters, whose sound was close enough to /w/. Among these, there is the letter gamma (γ), attested mostly but not only in the Lexicon of Hesychius. Given what we know about the sound of gamma, it is difficult to explain this use. The most straightforward hypothesis suggests that the scribes who copied these words misread the capital digamma (Ϝ) as gamma (Γ). Presenting new and old evidence of gamma used to denote digamma in Ancient Greek literary and documen- tary papyri, lexicography, and medieval manuscripts, this paper refutes this hypoth- esis, and demonstrates that a peculiar evolution in the pronunciation of gamma in Post-Classical Greek triggered a systematic use of this letter to denote the sound once represented by the digamma. Keywords Ancient Greek language – gamma – digamma – Greek phonetics – Hesychius – lexicography © Francesco Camagni, 2020 | doi:10.1163/1568525X-bja10018 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY 4.0Downloaded license. from Brill.com09/30/2021 01:54:17PM via free access 2 Camagni 1 Introduction It is well known that many ancient Greek dialects preserved the /w/ sound into the historical period, contrary to Attic-Ionic and Koine Greek. -

Fraternity & Sorority Life Awards 2017-2018

FRATERNITY & SORORITY LIFE AWARDS 2017-2018 The Fraternity and Sorority Awards are designed to provide an objective assessment of a chapter’s performance. The evaluation process for these awards is completed through active reporting and nominations that are submitted online. This process is implemented not as a competition, but as a way for every chapter to measure their growth as an organization on an annual basis. The opportunity for recognition is provided to chapters that excel in the areas of academics, service, and Greek unity. Distinguished Chapters Distinguished Chapter honors are given only to chapters who earn high marks in all five areas of focus on the Stockton accreditation program, the Growth & Recognition Plan: academic achievement, leadership development, chapter operations, programming, and risk reduction. This year’s Distinguished Chapters are: Chi Upsilon Sigma National Latin Sorority, Inc. Delta Phi Epsilon Mu Sigma Upsilon Sorority, Inc. Sigma Beta Rho Fraternity, Inc. Zeta Tau Alpha Outstanding Educational Program Iota Phi Theta Fraternity, Inc. – Male Empowerment Film & Discussion Outstanding Collaborative Program Iota Phi Theta Fraternity, Inc. – Museum Bus Trip with Sankofa Outstanding Philanthropy Program Sigma Beta Rho Fraternity, Inc. – SOS Children’s Villages Charity Dinner Outstanding Overall Programming Mu Sigma Upsilon Sorority, Inc. Academic Achievement Delta Delta Delta Kappa Sigma Achievement in Philanthropy Delta Delta Delta Kappa Sigma Zeta Tau Alpha Harry J. Maurice Service Award Delta Delta Delta Kappa Sigma Mu Sigma Upsilon Sorority, Inc. Sigma Beta Rho Fraternity, Inc. Interfraternal Community Award Jessica Landow, Delta Delta Delta FRATERNITY & SORORITY LIFE AWARDS 2017-2018 Ritual Award Delta Delta Delta Outstanding New Member Kyle Somers, Kappa Sigma Viona Richardson, Mu Sigma Upsilon Sorority, Inc. -

Phi Nu By-Laws.Docx

The By-laws of the Phi Nu Chapter of Psi Upsilon Article I Name: The name of the chapter shall be Phi Nu chapter of Psi Upsilon Fraternity. Article II Mission Statement: The Phi Nu Chapter of Psi Upsilon endeavors to become and maintain the highest standard of excellence within Christopher Newport University, the Newport News community, and the country at large; and to accept and create a membership committed to its ideals and social measures: always striving to and achieving the highest moral, intellectual, and physical excellence in all the days of the member's life. The membership shall actively embody and represent its ideals outwardly, becoming an example to its surrounding communities, so that when Phi Nu's membership graduates out of active involvement, they shall branch out and seek to improve every community they join. Purpose ● To uphold and preserve a high standard of moral principles for the group and each one of its members. ● To work with one another to meet spiritual, emotional, and mental needs of each of the individual members. ● To promote brotherhood and lasting unity between members. Article III Section 1. General Membership A Any student of Christopher Newport University who is recognized to be in good standing by its faculty and trustees is eligible for membership. Section 2. Member Requirements A Must maintain a GPA that meets the requirements of the National Fraternity Requirement. B Must possess a genuine desire to uphold and reflect the goals and values of the Psi Upsilon Fraternity. C Must participate in group service activities as determined by the chapter each semester. -

Beta Upsilon Lambda Chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc. in Partn

1 “Manly Deeds, Scholarship and Love for All Mankind” Beta Upsilon Lambda Chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc. in partnership with West Tennessee Community Initiative invites you to apply for the “GO TO HIGH SCHOOL, GO TO COLLEGE” 2021 DR. GLEN VAULX SCHOLARSHIP ALPHA PHI ALPHA FRATERNITY, INC. IS THE FIRST INTERCOLLEGIATE GREEK LETTER FRATERNITY FOUNDED BY AFRICAN AMERICAN MEN. It was founded at Cornell University in Ithaca, NY on December 4, 1906. The Fraternity’s national program on education dates back to 1919 with the introduction of our “Go to High School, Go to College'' national program. The purpose of the program is to increase the educational matriculation of African-Americans into college. The objectives of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc. are to stimulate the ambitions of both its members and the community preparing them for the greatest usefulness in the causes of humanity, freedom and dignity of the individual; to encourage the highest and noblest forms of manhood; and to aid downtrodden humanity in its efforts to achieve higher social, economic and intellectual status. ALL APPLICATIONS AND SUPPORTING MATERIALS MUST BE RECEIVED OR POSTMARKED BY APRIL 16, 2021. ANY APPLICATIONS POSTMARKED OR RECEIVED AFTER THAT DATE WILL NOT BE CONSIDERED. Dr. Glen Vaulx Scholarship Criteria 2 This scholarship is extended to all graduating seniors in good standing attending an accredited public high school throughout Madison County and its contiguous counties. Scholarship amounts may vary and will be determined by the Scholarship Committee annually. To be considered for a scholarship, the student MUST be accepted as a full-time freshman for the fall school term of 2021 at an accredited college or university. -

The Greek Alphabet & Pronunciation

Lesson 1 tHe Greek aLPHaBet & Pronunciation n this lesson, we learn how to identify and pronounce the letters of I the Greek alphabet. We also distinguish smooth and rough breathing marks and learn the sounds of Greek diphthongs. Finally, we practice reading a few Greek words, such as Ἀχαιός, ἴφθιμος, and προϊάπτω. The classical Greek alphabet has 24 letters (plus two archaic letters that help explain older forms of Greek). Greek Latin Greek Latin Letter Equivalents Sound Name Transcription a as in father (when short, as Α, α A, a ἄλφα alpha in aha) Β, β B, b b as in bite βῆτα beta always g as in get (never soft, Γ, γ G, g γάμμα gamma as in gym) Δ, δ D, d d as in deal δέλτα delta Ε, ε E, e e as in red ἒ ψιλόν epsilon zd as in Mazda (many also pronounce this dz or simply z, Ζ, ζ Z, z because these are simpler to ζῆτα zeta pronounce for native English speakers) long a as in gate or as in Η, η E, e ἦτα eta (French) fête Θ, θ th th as in thick θῆτα theta long e as in feet and police or , ι I, i ἰῶτα iota short i as in hit 2 , κ K, k or C, c k as in kill κάππα kappa , λ L, l l as in language λάμβδα lambda , μ M, m m as in man μῦ mu , ν N, n n as in never νῦ nu , ξ X, x x as in box ξῖ xi o as in ought, but shorter (that is, a “closed” o), or as , ο O, o ὂ μικρόν omicron in the British pronunciation of pot , π P, p p as in pie πῖ pi a trilled r (as in continental , ρ R, r ῥῶ rho European languages) Σ, σ, ς S, s s as in sing σίγμα sigma Τ, τ T, t t as in tip ταῦ tau u as in (French) tu or U, u or (German) Müller, but the u in Υ, υ ὖ ψιλόν upsilon -

Task Force for the Review of the Romanization of Greek RE: Report of the Task Force

CC:DA/TF/ Review of the Romanization of Greek/3 Report, May 18, 2010 page: 1 TO: ALA/ALCTS/CCS/Committee on Cataloging: Description and Access (CC:DA) FROM: ALA/ALCTS/CCS/CC:DA Task Force for the Review of the Romanization of Greek RE: Report of the Task Force CHARGE TO THE TASK FORCE The Task Force is charged with assessing draft Romanization tables for Greek, educating CC:DA as necessary, and preparing necessary reports to support the revision process, leading to ultimate approval of an updated ALA-LC Romanization scheme for Greek. In particular, the Task Force should review the May 2010 draft for a timely report by ALA to LC. Review of subsequent tables may be called for, depending on the viability of this latest draft. The ALA-LC Romanization table - Greek, Proposed Revision May 2010 is located at the LC Policy and Standards Division website at: http://www.loc.gov/catdir/cpso/romanization/greekrev.pdf [archived as a supplement to this report on the CC:DA site] BACKGROUND INFORMATION FROM THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS We note that when the May 2010 Greek table was presented for general review via email, the LC Policy and Standards Division offered the following information comparing the May 2010 table with the existing table, Greek (Also Coptic), available at the LC policy and Standards Division web site at: http://www.loc.gov/catdir/cpso/romanization/greek.pdf: "The Policy and Standards Division has taken another look at the revised Greek Romanization tables in conjunction with comments from the library community and its own staff with knowledge of Greek. -

Constitution of Corazones Unidos Siempre Chi Upsilon Sigma National Latin Sorority, Incorporated

CONSTITUTION OF CORAZONES UNIDOS SIEMPRE CHI UPSILON SIGMA NATIONAL LATIN SORORITY, INCORPORATED PREAMBLE We, the members of Chi Upsilon Sigma National Latin Sorority, Incorporated, aware of the prejudices and obstacles facing the women of color in our communities, dedicate ourselves to the improvement of these conditions and working towards the betterment of all women. We have unified ourselves through the sisterhood of Corazones Unidos Siempre and by our Founders' ideals of open communication and community service, as well as the development of a political, educational, social, and cultural awareness. We devote ourselves to this challenge, to be achieved through hard work, patience, and the collective effort to educate, as exemplified in our motto, "Wisdom Through Education." It is by this Constitution that we shall govern ourselves to the realization of these ideals. ARTICLE I. NAME This organization shall be known as Corazones Unidos Siempre, Chi Upsilon Sigma National Latin Sorority, Incorporated. Commonly known as Chi Upsilon Sigma, and hereinafter referred to as “the sorority”. ARTICLE II. PURPOSE The purpose of this sorority shall be: A) To develop an educational, cultural, political, and social awareness; B) To open lines of communications in order to service the community; C) To promote and preserve the Latino culture; D) To provide women with a choice among Greek letter sororities. ARTICLE III. MEMBERSHIP Section 1 General member 1.1 Members of this sorority shall consist of those women initiated and/or inducted by the Grand Chapter Board or a recognized chapter. 1.2 A member shall receive all rights and privileges bestowed upon her by this sorority. -

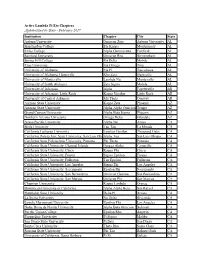

Active Lambda Pi Eta Chapters Alphabetized by State

Active Lambda Pi Eta Chapters Alphabetized by State - February 2017 Institution Chapter City State Auburn University Omicron Zeta Auburn University AL Huntingdon College Eta Kappa Montgomery AL Miles College Alpha Gamma Iota Fairfield AL Samford University Omicron Rho Birmingham AL Spring Hill College Psi Delta Mobile AL Troy University Eta Omega Troy AL University of Alabama Eta Pi Tuscaloosa AL University of Alabama, Huntsville Rho Zeta Huntsville AL University of Montevallo Lambda Nu Montevallo AL University of South Alabama Zeta Sigma Mobile AL University of Arkansas Alpha Fayetteville AR University of Arkansas, Little Rock Kappa Upsilon Little Rock AR University of Central Arkansas Mu Theta Conway AR Arizona State University Kappa Zeta Phoenix AZ Arizona State University Alpha Alpha Omicron Tempe AZ Grand Canyon University Alpha Beta Sigma Phoenix AZ Northern Arizona University Omega Delta Glendale AZ Azusa Pacific University Alpha Nu Azusa CA Biola University Tau Tau La Mirada CA California Lutheran University Upsilon Upsilon Thousand Oaks CA California Polytechnic State University, San Luis ObispoAlpha Tau San Luis Obispo CA California State Polytechnic University, Pomona Phi Theta Pomona CA California State University, Channel Islands Omega Alpha Camarillo CA California State University, Chico Kappa Phi Chico CA California State University, Fresno Sigma Epsilon Fresno CA California State University, Fullerton Tau Epsilon Fullerton CA California State University, Los Angeles Sigma Phi Los Angeles CA California State University, -

The Mathspec Package Font Selection for Mathematics with Xǝlatex Version 0.2B

The mathspec package Font selection for mathematics with XƎLaTEX version 0.2b Andrew Gilbert Moschou* [email protected] thursday, 22 december 2016 table of contents 1 preamble 1 4.5 Shorthands ......... 6 4.6 A further example ..... 7 2 introduction 2 5 greek symbols 7 3 implementation 2 6 glyph bounds 9 4 setting fonts 3 7 compatability 11 4.1 Letters and Digits ..... 3 4.2 Symbols ........... 4 8 the package 12 4.3 Examples .......... 4 4.4 Declaring alphabets .... 5 9 license 33 1 preamble This document describes the mathspec package, a package that provides an interface to select ordinary text fonts for typesetting mathematics with XƎLaTEX. It relies on fontspec to work and familiarity with fontspec is advised. I thank Will Robertson for his useful advice and suggestions! The package is developmental and later versions might to be incompatible with this version. This version is incompatible with earlier versions. The package requires at least version 0.9995 of XƎTEX. *v0.2b update by Will Robertson ([email protected]). 1 Should you be using this package? If you are using another LaTEX package for some mathematics font, then you should not (unless you know what you are doing). If you want to use Asana Math or Cambria Math (or the final release version of the stix fonts) then you should be using unicode-math. Some paragraphs in this document are marked advanced. Such paragraphs may be safely ignored by basic users. 2 introduction Since Jonathan Kew released XƎTEX, an extension to TEX that permits the inclusion of system wide Unicode fonts and modern font technologies in TEX documents, users have been able to easily typeset documents using readily available fonts such as Hoefler Text and Times New Roman (This document is typeset using Sabon lt Std).