The Effects of Neuregulin-1Β on Intrafusal Muscle Fiber Formation In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Somatosensory Systems

Somatosensory Systems Sue Keirstead, Ph.D. Assistant Professor Dept. of Integrative Biology and Physiology Stem Cell Institute E-mail: [email protected] Tel: 612 626 2290 Class 9: Somatosensory System (p. 292-306) 1. Describe the 3 main types of somatic sensations: 1. tactile: light touch, deep pressure, vibration, cold, hot, etc., 2. pain, 3. Proprioception. 2. List the types of sensory receptors that are found in the skin (Figure 9.11) and explain what determines the optimum type of stimulus that will activate each. 3. Describe the two different modality-specific ascending somatosensory pathways and note which modalities are carried in each (Figure 9.10 and 9.13). 4. Describe how it is possible for us to differentiate between stimuli of different modalities in the same body part (i.e. fingertip). Consider this at the level of 1) the sensory receptors and 2) the neurons onto which they synapse in the ascending sensory systems. 5. Explain how one might determine the location of a spinal cord injury based on the modality of sensation that is lost and the region of the body (both the side of the body and body part) where sensation is lost (Figure 9.18). 6. Describe how incoming sensory inputs from primary sensory axons can be modified at the level of the spinal cord and relate this to the mechanism of action of some common pain medications (Figure 9-18). 7. Describe the homunculus and explain the significance of the size of the region of the somatosensory cortex devoted to a particular body part. Cerebral cortex Interneuron Thalamus Interneuron 4 Integration of sensory Stimulus input in the CNS 1 Stimulation Sensory Axon of sensory of sensory receptor neuron receptor Graded potential Action potentials 2 Transduction 3 Generation of of the stimulus action potentials Copyright © 2016 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. -

Proprioceptive- Deep Tendon Reflex Dr. Jose Palomar

PROPRIOCEPTIVE- DEEP TENDON REFLEX DR. JOSE PALOMAR PROPRIOCEPTIVE- DEEP TENDON REFLEX DR. JOSE PALOMAR Proprioceptive-Deep Tendon Reflex About the Author Dr. Jose Palomar Lever, M.D. is a native of Guadalajara, the capital city of the state of Jalisco in Mexico. He began his medical school education at the age of 17 at the Universidad Autónoma de Guadalajara (UAG) and received his training in Orthopedic Surgery and Traumatology at the Universidad del Ejercito y Fuerza Aérea (UDEFA). He performed his first orthopedic surgery at the age of 24 and between 1984 and 1988 was an orthopedic surgeon on the staff of the Reconstructive and Plastic Surgery Institute of Jalisco, S.S.A. He went on to receive specialized training in minimally invasive spine surgery at the Texas Back Institute in Dallas, Texas. Pursuing his interest in what he now refers to as the “software” of the human body, a study, which began in earnest for him in 2000, Dr. Palomar became a Diplomate in Applied Kinesiology from the International College of Applied Kinesiology (ICAK). He received the organization's Alan Beardall Memorial Award for Research for 2004-2005 and over the years has had eighteen papers accepted for inclusion in ICAK-USA Proceedings. He also completed the Carrick Institute for Graduate Studies program in Clinical Neurology. Today, in addition to pursuing an ongoing research program, Dr. Palomar conducts regular trainings in Proprioceptive-Deep Tendon Reflex (P-DTR) for medical practitioners in USA, Canada, Australia, Mexico, England, Poland, Latvia and Russia, and continues to practice medicine from his home base in Guadalajara, Mexico. -

Tissue Engineered Myelination and the Stretch Reflex Arc Sensory Circuit: Defined Medium Ormulation,F Interface Design and Microfabrication

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2009 Tissue Engineered Myelination And The Stretch Reflex Arc Sensory Circuit: Defined Medium ormulation,F Interface Design And Microfabrication John Rumsey University of Central Florida Part of the Biology Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Doctoral Dissertation (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Rumsey, John, "Tissue Engineered Myelination And The Stretch Reflex Arc Sensory Circuit: Defined Medium Formulation, Interface Design And Microfabrication" (2009). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 3826. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/3826 TISSUE ENGINEERED MYELINATION AND THE STRETCH REFLEX ARC SENSORY CIRCUIT: DEFINED MEDIUM FORMULATION, INTERFACE DESIGN AND MICROFABRICATION by JOHN WAYNE RUMSEY B.S. University of Florida, 2001 M.S. University of Central Florida, 2004 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Burnett School of Biomedical Sciences in the College of Medicine at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2009 Major Professor: James J. Hickman ABSTRACT The overall focus of this research project was to develop an in vitro tissue- engineered system that accurately reproduced the physiology of the sensory elements of the stretch reflex arc as well as engineer the myelination of neurons in the systems. In order to achieve this goal we hypothesized that myelinating culture systems, intrafusal muscle fibers and the sensory circuit of the stretch reflex arc could be bioengineered using serum-free medium formulations, growth substrate interface design and microfabrication technology. -

BRS Physiology 3Rd Edition

Board Review Series • Reflects USMLE changes • Approximately 350 USMLE-type questions with explanations • Numerous illustrations, diagrams, and tables • Easy-to-follow outline covering all USMLE-tested topics • A comprehensive examination V Ah, LIPPINCOTT -"*" WILLIAMS &WILKIN; mum IEEE mows IF 'IMP IMMO MINK I I. Key Physiology Topics for USMLE Step I Cell Physiology Transport mechanisms Ionic basis for action potential Excitation-contraction coupling in skeletal, cardiac, and smooth muscle Neuromuscular transmission Autonomic Physiology Cholinergic receptors Adrenergic receptors Effects of autonomic nervous system on organ system function Cardiovascular Physiology Events of cardiac cycle Pressure, flow, resistance relationships Frank-Starling law of the heart Ventricular pressure-volume loops Ionic basis for cardiac action potentials Starling forces in capillaries Regulation of arterial pressure (baroreceptors and renin-angiotensin II-aldosterone system) Cardiovascular and pulmonary responses to exercise Cardiovascular responses to hemorrhage Cardiovascular responses to changes in posture Respiratory Physiology Lung and chest-wall compliance curves Breathing cycle Hemoglobin-02 dissociation curve Causes of hypoxemia and hypoxia vq, P02, and P00 2 in upright lung V/Q defects Peripheral and central chemoreceptors in control of breathing Responses to high altitude Renal and Acid-Base Physiology Fluid shifts between body fluid compartments Starling forces across glomerular capillaries Transporters in various segments of nephron (Na Cl-, -

Cortex Brainstem Spinal Cord Thalamus Cerebellum Basal Ganglia

Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology HST.131: Introduction to Neuroscience Course Director: Dr. David Corey Motor Systems I 1 Emad Eskandar, MD Motor Systems I - Muscles & Spinal Cord Introduction Normal motor function requires the coordination of multiple inter-elated areas of the CNS. Understanding the contributions of these areas to generating movements and the disturbances that arise from their pathology are important challenges for the clinician and the scientist. Despite the importance of diseases that cause disorders of movement, the precise function of many of these areas is not completely clear. The main constituents of the motor system are the cortex, basal ganglia, cerebellum, brainstem, and spinal cord. Cortex Basal Ganglia Cerebellum Thalamus Brainstem Spinal Cord In very broad terms, cortical motor areas initiate voluntary movements. The cortex projects to the spinal cord directly, through the corticospinal tract - also known as the pyramidal tract, or indirectly through relay areas in the brain stem. The cortical output is modified by two parallel but separate re entrant side loops. One loop involves the basal ganglia while the other loop involves the cerebellum. The final outputs for the entire system are the alpha motor neurons of the spinal cord, also called the Lower Motor Neurons. Cortex: Planning and initiation of voluntary movements and integration of inputs from other brain areas. Basal Ganglia: Enforcement of desired movements and suppression of undesired movements. Cerebellum: Timing and precision of fine movements, adjusting ongoing movements, motor learning of skilled tasks Brain Stem: Control of balance and posture, coordination of head, neck and eye movements, motor outflow of cranial nerves Spinal Cord: Spontaneous reflexes, rhythmic movements, motor outflow to body. -

Sensorimotor Deficits Following Oxaliplatin Chemotherapy

Wright State University CORE Scholar Browse all Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2017 Sensorimotor Deficits ollowingF Oxaliplatin Chemotherapy Jacob Adam Vincent Wright State University Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all Part of the Biomedical Engineering and Bioengineering Commons Repository Citation Vincent, Jacob Adam, "Sensorimotor Deficits ollowingF Oxaliplatin Chemotherapy" (2017). Browse all Theses and Dissertations. 2074. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all/2074 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Browse all Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SENSORIMOTOR DEFICITS FOLLOWING CHEMOTHERAPY A Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By JACOB ADAM VINCENT B.S. The Ohio State University, 2009 2017 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL April, 14 2017 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE DISSERTATION PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Jacob Adam Vincent ENTITLED Sensorimotor Deficits Following Chemotherapy BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFUILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Doctor of Philosophy. Timothy C. Cope, Ph.D. Dissertation Director Mill W. Miller, Ph.D. Director, Biomedical Sciences Ph.D. Program Robert E.W. Fyffe Ph.D. Vice President for Research and Dean of the Graduate School Committee on Final Examination Timothy C. Cope, Ph.D. Mark M. Rich, M.D.,Ph.D. Mill W. Miller, Ph.D. David Ladle, Ph.D. F. Javier Alvarez-Leefmans, M.D., Ph.D. Abstract Vincent, Jacob Adam. -

The Human Nervous System S Tructure and Function

The Human Nervous System S tructure and Function S ixth Ed ition The Human Nervous System Structure and Function S ixth Edition Charles R. Noback, PhD Professor Emeritus Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology College of Physicians and Surgeons Columbia University, New York, NY Norman L. Strominger, PhD Professor Center for Neuropharmacology and Neuroscience Department of Surgery (Otolaryngology) The Albany Medical College Adjunct Professor, Division of Biomedical Science University at Albany Institute for Health and the Environment Albany, NY Robert J. Demarest Director Emeritus Department of Medical Illustration College of Physicians and Surgeons Columbia University, New York, NY David A. Ruggiero, MA, MPhil, PhD Professor Departments of Psychiatry and Anatomy and Cell Biology Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons New York, NY © 2005 Humana Press Inc. 999 Riverview Drive, Suite 208 Totowa, New Jersey 07512 www.humanapress.com All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording, or otherwise without written permission from the Publisher. All papers, comments, opinions, conclusions, or recommendations are those of the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This publication is printed on acid-free paper. h ANSI Z39.48-1984 (American Standards Institute) Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. Production Editor: Tracy Catanese Cover design by Patricia F. Cleary Cover Illustration: The cover illustration, by Robert J. Demarest, highlights synapses, synaptic activity, and synaptic-derived proteins, which are critical elements in enabling the nervous system to perform its role. -

6-Stretch Reflex

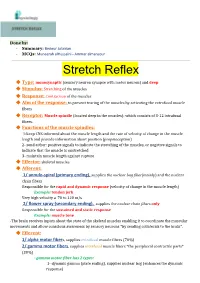

Done by: - Summary: Bedour Julaidan . - MCQs: Muneerah alHussaini - Ammar almansour Stretch Reflex ❖ Type: monosynaptic (sensory neuron synapse with motor neuron) and deep ❖ Stimulus: Stretching of the muscles ❖ Response: Contraction of the muscles ❖ Aim of the response: to prevent tearing of the muscles by activating the extrafusal muscle fibers ❖ Receptor: Muscle spindle (located deep in the muscles): which consists of 3-12 intrafusal fibers. ❖ Functions of the muscle spindles: 1-keep CNS informed about the muscle length and the rate of velocity of change in the muscle length and provide information about position (proprioception) 2- send either: positive signals to indicate the stretching of the muscles, or negative signals to indicate that the muscle is unstretched 3- maintain muscle length against rupture ❖ Effector: skeletal muscles ❖ Afferent: 1/ annulo-spiral (primary ending), supplies the nuclear bag fiber(mainly) and the nuclear chain fibers Responsible for the rapid and dynamic response (velocity of change in the muscle length) Example: tendon jerk Very high velocity a 70 to 120 m/s 2/ flower spray (secondary ending), supplies the nuclear chain fibers only Responsible for the sustained and static response Example: muscle tone -The brain receives inputs about the state of the skeletal muscles enabling it to coordinate the muscular movements and allow conscious awareness by sensory neurons *by sending collaterals to the brain*. ❖ Efferent: 1/ alpha motor fibers, supplies -

Malak Shalfawi Noor Adnan Lina Abdelhadi Fasial Mohammad

9 Noor Adnan Malak Shalfawi Lina abdelhadi Fasial Mohammad 0 Motor system – Motor of the spinal cord Before we start talking about the motor function of the spinal cord, let’s first take a quick look at the motor system and the incredible connections taking place inside it: [please refer to the pictures for better understanding] 1- Motor command For any motor function (movement) to occur, the nervous system has motor command that comes from the cerebral motor cortex to the spinal cord and these descending tracts (corticospinal) are called also pyramidal tracts and that’s because they pass through the pyramids of medulla oblongata. The neuronal fibers coming from the cortex ending in the spinal cord are considered upper motor neurons, while the neuronal fibers going out from the spinal cord to reach the muscles are called lower motor neurons. There are other origins for the motor commands such as the brain stem and the red nucleus that send neuronal fibers to the spinal cord in order to control the activity of the muscles. 2- Motor command intension At the same time, there are some tracts going from the cortex to the cerebellum through the brain stem like the corticopontocerebellar, corticoreticulocerebellar, corticolivarycerebellar tracts. And these tracts are telling the cerebellum about the intended movements. (= the movements we want to do) 3-motor command monitor/ feedback system a- Inside the muscles we have receptors (muscle spindles/ stretch receptors, Golgi tendon organs) that are connected to sensory (afferent) neuronal fibers that goes to the spinal cord relay nuclei. 1 | P a g e b- From the spinal cord they go to the cerebellum through ventral and dorsal spinocerebellar tracts to tell the cerebellum what is exactly happening down at the level of the muscles. -

SENSORIMOTOR DEFICITS FOLLOWING CHEMOTHERAPY a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of Requirements for the Degree Of

SENSORIMOTOR DEFICITS FOLLOWING CHEMOTHERAPY A Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By JACOB ADAM VINCENT B.S. The Ohio State University, 2009 2017 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL April, 14 2017 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE DISSERTATION PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Jacob Adam Vincent ENTITLED Sensorimotor Deficits Following Chemotherapy BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFUILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Doctor of Philosophy. Timothy C. Cope, Ph.D. Dissertation Director Mill W. Miller, Ph.D. Director, Biomedical Sciences Ph.D. Program Robert E.W. Fyffe Ph.D. Vice President for Research and Dean of the Graduate School Committee on Final Examination Timothy C. Cope, Ph.D. Mark M. Rich, M.D.,Ph.D. Mill W. Miller, Ph.D. David Ladle, Ph.D. F. Javier Alvarez-Leefmans, M.D., Ph.D. Abstract Vincent, Jacob Adam. Ph.D., Biomedical Sciences Ph.D. Program, Wright State University, 2017. Sensorimotor Deficits Following Oxaliplatin Chemotherapy. Neurotoxicity is one of the most significant side effects diminishing clinical efficacy and patient quality of life during and following chemotherapy. Oxaliplatin (OX) is a platinum based chemotherapy agent used in the treatment of colorectal cancer. Colorectal cancer currently ranks as the 4th most common cancer, and the majority of patients receive OX as a part of their adjuvant therapy. OX based adjuvant therapies significantly improve 5 year survival rates, however in many cases patients must stop treatment early because of the neurotoxic side effects. OX causes two clinically distinct forms of neurotoxicity. Acutely, within hours and for days following OX infusion patients experience positive symptoms including, paresthesia, cold induced pain, and muscle cramping/fasciculation. -

Neurophysiology Reflexes Department of Physiology

NEUROPHYSIOLOGY REFLEXES DEPARTMENT OF PHYSIOLOGY DR. K. MEDAGODA REFLEX • A RAPID AUTOMATIC RESPONSE TO A STIMULUS. • CARRIED OUT BY A RELATIVELY SIMPLE NEURAL CIRCUIT. • KNOWN AS - REFLEX ARC • CONSIDERED AS THE BASIC UNIT OF NEURAL ACTIVITY. • REFLEX ARC CONSISTS OF • A SENSE ORGAN • AFFERENT NEURON • ONE OR MORE CENTRAL SYNAPSES • AN EFFERENT NEURON • AN EFFECTOR ( MUSCLE,GLAND) Dr Kushan Medagoda – Neurophysiology Reflexes REFLEX ARC • AFFERENT FIBERS • TRAVEL ALONG THE DORSAL ROOTS OR CRANIAL NERVES . • CELL BODIES LIE IN THE DORSAL ROOT GANGLIA OR CRANIAL NERVE GANGLIA. • EFFERENT FIBERS • LEAVE VIA THE VENTRAL ROOTS OR CORRESPONDING MOTOR CRANIAL NERVES. Dr Kushan Medagoda – Neurophysiology Reflexes THE REFLEX ARC Dr Kushan Medagoda – Neurophysiology Reflexes TYPES OF REFLEXES • MONOSYNAPTIC REFLEXES • DISYNAPTIC REFLEXES • POLYSYNAPTIC REFLEXES • MONOSYNAPTIC REFLEXES • HAS ONLY ONE SYNAPSE BETWEEN THE AFFERENT AND EFFERENT NEURONS E.G. STRETCH REFLEX • POLYSYNAPTIC REFLEXES • HAS ONE OR MORE INTERNEURONS BETWEEN AFFERENT AND EFFERENT NEURON. • HAS TWO OR MORE SYNAPSES IN THE ARC. • E.G. WITHDRAWAL REFLEX Dr Kushan Medagoda – Neurophysiology Reflexes MONOSYNAPTIC REFLEXES THE STRETCH REFLEX • WHEN A SKELETAL MUSCLE WITH AN INTACT NERVE SUPPLY IS STRETCHED, IT CONTRACTS. • STIMULUS -STRETCH OF THE MUSCLE • SENSE ORGAN -MUSCLE SPINDLE • AFFERENT -FAST SENSORY FIBERS • EFFERENT - MOTOR NEURONS • EFFECTOR- MUSCLE • EFFECT- CONTRACTION OF THE MUSCLE • IMPORTANT TO MAINTAIN THE MUSCLE TONE. Dr Kushan Medagoda – Neurophysiology Reflexes -

The Role of the Spinal Cord Is Secondary to That of the Brain

Unit VII – Problem 7 – Physiology: Motor Functions of The Spinal Cord; The Cord Reflexes - The role of the spinal cord is secondary to that of the brain. - Circuits exist in the spinal cord, however, that process sensory information and are capable of generating complex motor activity. - Organization of the spinal cord for motor functions: Anterior (ventral) horn motor neurons: Present at levels of the spinal cord. Innervate skeletal striated muscles. Note that a motor neuron and all the muscle fibers it innervates are referred to collectively as a (motor unit). There are two types of motor neurons in the ventral horn: Alpha motor neurons: myelinated axons, 14 micrometers in diameter, high conduction velocity. Gamma motor neurons: 5 micrometers in diameter, low conduction velocity. Interneuron: They are 30 times more numerous than motor neurons. Highly excitable. Spontaneous firing rates as high as 1500/sec. They receive the bulk of synaptic input that reaches the spinal cord, as either incoming sensory information or as signals descending from higher centers in the brain. Renshaw cell: a type of interneuron. It receives input from collateral branches of motor neuron axons and then, via its own axonal system, provides inhibitory connections with the same or neighboring motor neurons. - Muscle sensory receptors (muscle spindles and Golgi tendon organs) and their roles in muscle control: Receptor function of the muscle spindle: The sensory feedback from muscles include: Current length of the muscle. The length value is derived from a muscle spindle. Current tension in the muscle. Tension is signaled by a Golgi tendon organ. Muscle spindle: 3-10 mm in length.