Performance and Plot in the Ozidi Saga

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![The Canon, [1972-73]: Volume 3, Number 4](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9514/the-canon-1972-73-volume-3-number-4-649514.webp)

The Canon, [1972-73]: Volume 3, Number 4

Digital Collections @ Dordt Dordt Canon University Publications 1973 The Canon, [1972-73]: Volume 3, Number 4 Dordt College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.dordt.edu/dordt_canon Recommended Citation Dordt College, "The Canon, [1972-73]: Volume 3, Number 4" (1973). Dordt Canon. 55. https://digitalcollections.dordt.edu/dordt_canon/55 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at Digital Collections @ Dordt. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dordt Canon by an authorized administrator of Digital Collections @ Dordt. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Soli Deo Gloria CANNON DORDT COLLEGE, SIOUX CENTER, IOWA VOL. III -.- No.4 Mother Night: Victims of Change Victoria and Blue·Jeans Prof. James Koldenhoven by Pat De Young What Is Life? The old and the new, like jaws of a trap, have closed on the people of I saw Victoria Allison for the first ally she disagreed in discussion-too by Becky Maatman Tennessee Williams and John Osborne's time on satge. She walked out, long loudly in her curt, clipped Yankee ac- Vonnegut, author of Mother Night plays, The Glass Menagerie and Look swinging steps, took the mike, and cent. Having said what she wanted to asks, "What is a war criminal? Is it Back inAnger. Laura Wingfield iS1he quietly announced, "I will sing a selec- say, she would give her head a toss someone who has obeyed his conscience, central victim in Williams' American tion from Hair." Staring at the floor in and return to silence, eyes focused on perhaps doing wrong,",» is it someone (U.S.A.) culture in the 1930's and silence, she paused. -

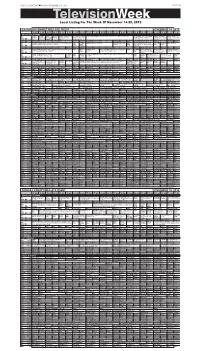

Televisionweek Local Listing for the Week of November 14-20, 2015

PRESS & DAKOTAN n FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 13, 2015 PAGE 9B TelevisionWeek Local Listing For The Week Of November 14-20, 2015 SATURDAY PRIMETIME/LATE NIGHT NOVEMBER 14, 2015 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 BROADCAST STATIONS Cook’s Victory Prairie America’s Classic Gospel Songs The Lawrence Welk High School Football SDHSAA Class 11AAA, Final: Teams TBA. (N) (Live) Rock Garden Tour: Soul Butter Austin City Limits Globe Trekker The PBS Country Garden’s Yard and Heartlnd of patriotism and Show California vaca- and Hogwash (In Stereo) Å “James Taylor” (N) (In history of tea; cultural KUSD ^ 8 ^ Å Garden faith. Å tion destinations. Stereo) Å traditions. KTIV $ 4 $ College Football Wake Forest at Notre Dame. (N) Å News 4 Insider Dateline NBC (In Stereo) Å Saturday Night Live News 4 Saturday Night Live (N) Å Extra (N) Å 1st Look House College Football Wake Forest at Notre Dame. From Notre Dame Sta- KDLT The Big Dateline NBC (In Stereo) Å Saturday Night Live KDLT Saturday Night Live Elizabeth The Simp- The Simp- KDLT News Å NBC dium in South Bend, Ind. (N) (In Stereo Live) Å News Bang (In Stereo) Å News Banks; Disclosure performs. (N) (In sons sons KDLT % 5 % (N) Å Theory (N) Å Stereo) Å KCAU ) 6 ) College Football Michigan at Indiana. (N) (Live) Score News Edition College Football Oklahoma at Baylor. -

Kurt Vonnegut Jr. Confronts the Death of the Author Justin Philip Mayerchak Florida International University, [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DigitalCommons@Florida International University Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 4-1-2016 Kurt Vonnegut Jr. Confronts the Death of the Author Justin Philip Mayerchak Florida International University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Mayerchak, Justin Philip, "Kurt Vonnegut Jr. Confronts the Death of the Author" (2016). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2440. http://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/2440 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida KURT VONNEGUT JR. CONFRONTS THE DEATH OF THE AUTHOR A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTERS OF ARTS in ENGLISH by Justin Philip Mayerchak 2016 To: Dean Michael R. Heithaus College of Arts, Sciences and Education This thesis, written by Justin Philip Mayerchak, and entitled Kurt Vonnegut Jr. Confronts the Death of the Author, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this thesis and recommend that it be approved. _______________________________________ Bruce Harvey _______________________________________ Ana Lusczynka _______________________________________ Nathaniel Cadle, Major Professor Date of Defense: April 1, 2016 The thesis of Justin Philip Mayerchak is approved. -

Follow Us on Facebook & Twitter @Back2past for Updates

1/30 - Golden to Modern Age Comics & Batman Collectibles 1/30/2021 This session will be begin closing at 6PM on 01/30/20, so be sure to get those bids in via Proxibid! Follow us on Facebook & Twitter @back2past for updates. Visit our store website at GOBACKTOTHEPAST.COM or call 313-533-3130 for more information! Get the full catalog with photos, prebid and join us live at www.proxibid.com/backtothepast! See site for full terms. LOT # QTY LOT # QTY 1 Auction Rules 1 15 Bat(h) Time Fun Batman Lot 1 All new condition. Towels, bath mat, crazy foam, and more! You 2 Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles #4 (1985) 1 Key first printing!! NM- condition. get all pictured. 3 Batman Black and White Statue/Neal Adams 1 16 Daredevil #176 Key/1st Stick 1 #546/3500. Approximately 6.75" tall. Opened only for inspection First appearance of Stick. NM- condition. and to photograph. 17 Daredevil #173 Frank Miller 1 Frank Miller Daredevil. VF+ condition. 4 Star Wars #4 (Marvel) 1977 1st Print 1 Part 4 of the A New Hope adaptation. VF condition. 18 The Mighty Crusaders #5 (1965) 1 From The Mighty Comics Group. VG+ condition. 5 Iron Man Vol. 3 #14 CGC 9.8 1 CGC graded comics. Fantastic Four appearance. 19 Daredevil #163 Hulk Cover/Frank Miller 1 Frank Miller Daredevil. VF- condition. 6 Dark Knight Returns Golden Child (x6) 1 Lot of (6) One-shot by Frank Miller set in the future timeline of The 20 Freedom Fighters Lot of (3) DC Bronze 1 Dark Knight Returns. -

•Œall Persons Living and Dead Are Purely Coincidental:•Š Unity, Dissolution, and the Humanist Wampeter of Kurt Vonnegu

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 4-2014 “All Persons Living and Dead Are Purely Coincidental:” Unity, Dissolution, and the Humanist Wampeter of Kurt Vonnegut’s Universe Danielle M. Clarke College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Clarke, Danielle M., "“All Persons Living and Dead Are Purely Coincidental:” Unity, Dissolution, and the Humanist Wampeter of Kurt Vonnegut’s Universe" (2014). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 56. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/56 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Clarke 2 Table of Contents: Introduction…………………………………………………………………..……………3 Reading Cosmically…………………………………………………………...…………12 Reading Thematically……………..……..………………………………………………29 Reading Holisitcally …………...…………...……………………………………………38 Reading Theoretically …………………………………………...………………………58 Conclusions………………………………………………………………………………75 Works Cited…………………………………………………………………...…………85 Works Consulted…………………………………………………………………………89 Clarke 3 Introduction “‘Being alive is a crock of shit’" (3) writes Kurt Vonnegut in the opening chapter of Timequake (1997), quoting “the old science fiction writer -

COOU Journal Nov. 2015 Main 13

ANSU Journal of Language and Literary Studies (AJLLS) Vol. 1 No. 2 December, 2015 © Department of English Chukwuemeka Odomegwu Ojukwu University, Anambra State. i OBJECTIVES ANSU Journal of Language and Literary Studies (AJLLS) is a peer reviewed Journal geared to sustaining progressive analytical and well researched papers in the studies of Language and Literature. It also publishes well written expository essays, reviews, poems and short stories in English and indigenous languages. SUBMISSION OF MANUSCRIPT Manuscript should be submitted for peer reviewing to:[email protected]. The AJLLS adopts the Modern Language Association MLA document style 6th or 7th edition or the latest edition of APA. Any case of piracy is solely at the risk of the individual contributor so accused. AJLLS is published twice a year June and December by the Department of English, Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University. ANSUJLLS ISSN 2465 - 7352 ii Editor-in-Chief Dr. Echezona Ifejirika Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University, Igbariam. Editor Dr. Ngozi Chuma-Udeh Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University, Igbariam. Associate Editor Dr. Ngozi Madu Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University, Igbariam. Editorial Members Dr. Anthonia Ezeugo - Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University, Igbariam. Dr. Chukwueloka Christian Chukwuloo - Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University, Igbariam. Okeke Fidelia - Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University, Igbariam. Ofoegbu Cyril - Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University, Igbariam. Editorial Secretary Dr. Asika Emmanuel Ikechukwu Consulting Editors -

THE MILITARY SYSTEM of BENIN KINGDOM, C.1440 - 1897

THE MILITARY SYSTEM OF BENIN KINGDOM, c.1440 - 1897 THESIS in the Department of Philosophy and History submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Hamburg, Germany By OSARHIEME BENSON OSADOLOR, M. A. from Benin City, Nigeria Hamburg, 23 July, 2001 DISSERTATION COMMITTEE FIRST EXAMINER Professor Dr. Leonhard Harding Doctoral father (Professor für Geschichte Afrikas) Historisches Seminar, Universität Hamburg SECOND EXAMINER Professor Dr. Norbert Finzsch (Professor für Aussereuropäische Geschichte) Historisches Seminar, Universität Hamburg CHAIR Professor Dr. Arno Herzig Prodekan Fachbereich Philosophie und Geschichtswissenchaft Universität Hamburg DATE OF EXAMINATION (DISPUTATION) 23 July, 2001 ii DECLARATION I, Osarhieme Benson Osadolor, do hereby declare that I have written this doctoral thesis without assistance or help from any person(s), and that I did not consult any other sources and aid except the materials which have been acknowledged in the footnotes and bibliography. The passages from such books or maps used are identified in all my references. Hamburg, 20 December 2000 (signed) Osarhieme Benson Osadolor iii ABSTRACT The reforms introduced by Oba Ewuare the Great of Benin (c.1440-73) transformed the character of the kingdom of Benin. The reforms, calculated to eliminate rivalries between the Oba and the chiefs, established an effective political monopoly over the exertion of military power. They laid the foundation for the development of a military system which launched Benin on the path of its imperial expansion in the era of the warrior kings (c.1440-1600). The Oba emerged in supreme control, but power conflicts continued, leading to continuous administrative innovation and military reform during the period under study. -

Early and Middle Childhood: Changing Patterns for Learning

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find ja good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Kurt Vonnegut in Flight Ten Stone Steps Lead up from the Sidewalk To

Kurt Vonnegut in Flight Ten stone steps lead up from the sidewalk to the front door of the Manhattan th brownstone row house at 228 East 48 Street where Kurt Vonnegut lived for the last thirty-four years of his life. He’d walked up and down those stairs on thousands of days, but on the sunny afternoon of March 14, 2007, he descended them for the last time. Taking his little dog out for their usual walk, Vonnegut apparently got tangled up in his pet’s leash and fell face forward onto the sidewalk. The resulting blow to his head sent him into a coma from which he was unable to recover. He died on April 11. He was 84. It was the end of one of the most remarkable lives of any great novelist of the second half th of the 20 Century. Vonnegut’s final fall was foreshadowed by the circumstances of an anecdote Kurt had loved to tell about his beloved sister Alice’s sense of humor. Kurt, Alice, and their older brother Bernard had grown up delighting in the vaudeville-style slapstick humor of the 1930s. On radio and in film, “Amos and Andy,” Charlie Chaplin, Laurel and Hardy, and other great comics portrayed ordinary people matter-of-factly persisting though insults, eye-pokes, and pratfalls, and thereby succeeding in turning pain into humor. Vonnegut’s anecdote about Alice described how the biggest laugh they ever shared happened one day when a city bus stopped suddenly right beside them: its door flew open, and an unfortunate passenger was thrown out (“horizontally,” as Alice afterwards insisted) onto the sidewalk at their feet. -

Mother-Night.Pdf

MOTHER NIGHT By Kurt Vonnegut, Adapted for the Stage by Sam Robers Act One (Lights up on center stage. In it we see an older man, perhaps only in his late forties or early fifties, but beaten down by a life of disappointment. There is a drugged look in his eyes, the look of a man who doesn't feel anything anymore. He sits at a typewriter.) Campbell: My name is Howard W. Campbell, Jr. I am an American by birth, a Nazi by reputation, and a nationless person by inclination. The year in which I write this book is 1961. I am behind bars. I am behind bars in a nice new jail in old Jerusalem. I am awaiting a fair trial for my war crimes by the Republic of Israel. I was born in Schenectady, New York, on February 16, 1912. My father, who was a Baptist minister, was an engineer in the Service Engineering Department of the General Electric Company. His job demanded such varied forms of technical cleverness of him that he had scant time and imagination left over for anything else. The man was the job and the job was the man. The only nontechnical book I ever saw him look at was a picture history of the First World War. He never told me what the book meant to him, and I never asked him. All he ever said was that it wasn't for children, that I wasn't to look at it. So of course I did. There were pictures of men hung on barbed wire, mutilated women, bodies stacked like cordwood - all the usual furniture of world wars. -

The Madness of Sanity a Study of Kurt Vonnegut's Mother Night

Hugvísindasvið The Madness of Sanity A Study of Kurt Vonnegut's Mother Night Ritgerð til B.A.-prófs í ensku Einar Steinn Valgarðsson Maí 2009 Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Deild erlendra tungumála, bókmennta og málvísinda The Madness of Sanity A Study of Kurt Vonnegut’s Mother Night Ritgerð til B.A.-prófs í ensku Einar Steinn Valgarðsson Kt.: 2208842529 Leiðbeinandi: Júlián Meldon D'Arcy Maí 2009 The Madness of Sanity: A Study of Kurt Vonnegut’s Mother Night. Summary In this essay I will examine the novel Mother Night by Kurt Vonnegut in terms of questions about responsibility, identity and moral schizophrenia, and of awareness and illusion. I will argue that the attempts of the novel’s main character, Howard W. Campbell Jr., to keep his sanity, given the situation he had put himself into (as a US spy in the Nazi hierarchy in Germany during World War II), may indeed be a sort of madness. Furthermore, I will explore the fine line in Vonnegut’s novel between seeming opposites such as between sanity and madness, and his presentation of the human trait of evasion in the sense of blocking or putting a barrier between two seemingly contradictory stances, between, say, feelings on the one hand and reason or conscience on the other, which, while in some instances are beneficial, also have the potential of having dire consequences, depending on how or if one acts upon them. I will argue that Campbell is a perfect example of this theme and that Vonnegut is pointing out the ambivalence of pushing your awareness or conscience to the corner of the room, not necessarily destroying it, but at least pushing it far enough away to allow yourself to do things that are in violation of it. -

Oral Tradition

_____________________________________________________________ Volume 9 March 1994 Number 1 _____________________________________________________________ Editor Editorial Assistants John Miles Foley Cathe Green Lewis Dave Henderson Catherine S. Quick Slavica Publishers, Inc. For a complete catalog of books from Slavica, with prices and ordering information, write to: Slavica Publishers, Inc. P.O. Box 14388 Columbus, Ohio 43214 ISSN: 0883-5365 Each contribution copyright © 1994 by its author. All rights reserved. The editor and the publisher assume no responsibility for statements of fact or opinion by the authors. Oral Tradition seeks to provide a comparative and interdisciplinary focus for studies in oral literature and related fields by publishing research and scholarship on the creation, transmission, and interpretation of all forms of oral traditional expression. As well as essays treating certifiably oral traditions, OT presents investigations of the relationships between oral and written traditions, as well as brief accounts of important fieldwork, a Symposium section (in which scholars may reply at some length to prior essays), review articles, occasional transcriptions and translations of oral texts, a digest of work in progress, and a regular column for notices of conferences and other matters of interest. In addition, occasional issues will include an ongoing annotated bibliography of relevant research and the annual Albert Lord and Milman Parry Lectures on Oral Tradition. OT welcomes contributions on all oral literatures, on all literatures directly influenced by oral traditions, and on non-literary oral traditions. Submissions must follow the list-of- reference format (style sheet available on request) and must be accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope for return or for mailing of proofs; all quotations of primary materials must be made in the original language(s) with following English translations.