Kurt Vonnegut in Flight Ten Stone Steps Lead up from the Sidewalk To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Patterson.Mobi 3Rd Degree

.mobi 1984- George Orwell.mobi 1st to Die- James Patterson.mobi 2nd Chance- James Patterson.mobi 3rd Degree- James Patterson.mobi 61 Hours - Lee Child.mobi 9 Dragons- Michael Connelly.mobi A Bend in the Road- Nicholas Sparks.mobi A Brief History of Time- Stephen Hawking.mobi A Canticle for Leibowitz- Walter M. Miller.mobi A Caress of Twilight - Laurell K. Hamilton.mobi A Catskill Eagle- Robert B. Parker.mobi A Christmas Carol- Charles Dickens.mobi A Clash of Kings- George R.R. Martin.mobi A Clockwork Orange- Anthony Burgess.mobi A Confederacy of Dunces- John Kennedy Toole.mobi A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court- Mark Twain.mobi A Crown of Swords- Robert Jordan.mobi A Dangerous Man- Charlie Huston.mobi A Darkness More Than Night- Michael Connelly.mobi A Day Late and a Dollar Short- Terry McMillan.mobi A Deepness in the Sky- Vernor Vinge.mobi A Dirty Job- Christopher Moore.mobi A Discovery of Witches- Deborah Harkness.mobi A Drink Before the War- Dennis Lehane.mobi A Farewell to Arms- Ernest Hemingway.mobi A Feast for Crows- George R.R. Martin.mobi A Fire Upon the Deep- Vernor Vinge.mobi A Fistful of Charms- Kim Harrison.mobi A Game Of Thrones- George R.R. Martin.mobi A Hat Full Of Sky- Terry Pratchett.mobi A History of God- Karen Armstrong.mobi A is for Alibi- Sue Grafton.mobi A Journey to the Center of the Earth- Jules Verne.mobi A King's Ransom- James Grippando.mobi A Kingdom Besieged- Raymond E. Feist.mobi A Kiss of Shadows- Laurell K. -

A Discourse of Redemption in Three of Kurt Vonnegut's Novels

Tutton Parker 1 What’s in the Potato Barn: A Discourse of Redemption in Three of Kurt Vonnegut’s Novels A Thesis Submitted to The Faculty of the College of Arts and Science in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts and English By Rebecca Tutton Parker April 2018 Tutton Parker 2 Liberty University College of Arts and Sciences Master of Arts in English Student Name: Rebecca Tutton Parker Thesis Chair Date First Reader Date Second Reader Date Tutton Parker 3 Table of Contents Chapter One: Introduction………………………………………………………………………...4 Chapter Two: Redemption in Slaughterhouse-Five and Bluebeard…………………………..…23 Chapter Three: Rabo Karabekian’s Path to Redemption in Breakfast of Champions…………...42 Chapter Four: How Rabo Karabekian Brings Redemption to Kurt Vonnegut…………………..54 Chapter Five: Conclusion………………………………………………………………………..72 Works Cited……………………………………………………………………………………..75 Tutton Parker 4 Chapter One: Introduction The Bluebeard folktale has been recorded since the seventeenth century with historical roots even further back in history. What is most commonly referred to as Bluebeard, however, started as a Mother Goose tale transcribed by Charles Perrault in 1697. The story is about a man with a blue beard who had many wives and told them not to go into a certain room of his castle (Hermansson ix). Inevitably when each wife was given the golden key to the room and a chance alone in the house, she would always open the door and find the dead bodies of past wives. She would then meet her own death at the hands of her husband. According to Casie Hermansson, the tale was very popular in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, which spurred many literary figures to adapt it, including James Boswell, Charles Dickens, Herman Melville, and Thomas Carlyle (x). -

It Is Easy to Interpret Kurt Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse-Five and Anthony

It is easy to interpret Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five and Anthony Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange as cynical and pessimistic novels. The profusion of graphic images involving death, gang violence, and war make it difficult to walk away from either text with a hopeful outlook for the future of mankind. Thus, many literary critics label Vonnegut and Burgess as fatalists who argue for an acceptance of deterministic forces that eventually cause humans harm and suffering. However, other critics, such as Liu Hong, Wayne McGinnis, Todd Davis, and Kenneth Womack, all contend that at the end of the day Vonnegut and Burgess offer an opinion of humanity that is hopeful and encouraging. To these critics, the authors ultimately argue that the individual has the ability to determine their own fate in a horrific and often hurtful world. The standard debate concerning these two revolutionary authors has thus been one between a message of either hope or disparagement. It is a debate that has long been discussed among literary critics and continues to be an ever-changing discussion. My contention is that both Vonnegut and Burgess each create a body of work that offers the reader hope, empowerment, and an optimistic outlook of a future that is better than their present, or rather the present setting of their characters. Thus, I agree with critics like McGinnis, who calls Slaughterhouse-Five Vonnegut’s “most hopeful novel to date” (McGinnis 121), or Davis and Womack, who find that A Clockwork Orange’s protagonist ultimately finds a hopeful and optimistic conclusion in embarking “…upon a lifetime of familial commitment and human renewal.” (Davis, Womack 34). -

The Cases of Venedikt Erofeev, Kurt Vonnegut, and Victor Pelevin

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Scholarship@Western Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-21-2012 12:00 AM Burying Dystopia: the Cases of Venedikt Erofeev, Kurt Vonnegut, and Victor Pelevin Natalya Domina The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Professor Calin-Andrei Mihailescu The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Natalya Domina 2012 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Domina, Natalya, "Burying Dystopia: the Cases of Venedikt Erofeev, Kurt Vonnegut, and Victor Pelevin" (2012). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 834. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/834 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BURYING DYSTOPIA: THE CASES OF VENEDIKT EROFEEV, KURT VONNEGUT, AND VICTOR PELEVIN (Spine Title: BURYING DYSTOPIA) (Thesis Format: Monograph) by Natalya Domina Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada Natalya Domina 2012 THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO SCHOOL OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES CERTIFICATE OF EXAMINATION Supervisor Examiners ____________________________ ________________________________ Prof. -

Cultural Schizophrenia and Science Fiction in Kurt Vonnegut’S

TIME SKIPS AND TRALFAMADORIANS: CULTURAL SCHIZOPHRENIA AND SCIENCE FICTION IN KURT VONNEGUT’S SLAUGHTERHOUSE-FIVE AND THE SIRENS OF TITAN Gina Marie Gallagher Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the Department of English, Indiana University May 2012 Accepted by the Faculty of Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts. Tom Marvin, Ph.D., Chair Master’s Thesis Committee Robert Rebein, Ph.D. Karen Johnson, Ph.D. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the English Department at Indiana University-Purdue University, Indianapolis, for accepting me as a student and continuing to challenge me as a scholar. This process would not have been possible without my thesis advisor and committee chair member, Dr. Tom Marvin, to whom I am forever indebted. It is also a pleasure to thank my thesis committee members, Dr. Robert Rebein and Dr. Karen Johnson. Their help and guidance was invaluable in this process and I am grateful to have had the opportunity to work with such talented professors. Additionally, I would like to extend my gratitude to the entire staff of the English department, in particular the very talented Pat King. I owe my deepest gratitude to my family, who remain the foundation of everything that I do, academic and otherwise. Thank you to my eternally patient, loving and supportive parents, as well as my unofficial literary advisors: Michael, Rory and Angela. iii ABSTRACT Gina Marie Gallagher TIME SKIPS AND TRALFAMADORIANS: CULTURAL SCHIZOPHRENIA AND SCIENCE FICTION IN KURT VONNEGUT’S SLAUGHTERHOUSE-FIVE AND THE SIRENS OF TITAN In his novels Slaughterhouse-five and The Sirens of Titan, Kurt Vonnegut explores issues of cultural identity in technologically-advanced societies post-World War II. -

![The Canon, [1972-73]: Volume 3, Number 4](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9514/the-canon-1972-73-volume-3-number-4-649514.webp)

The Canon, [1972-73]: Volume 3, Number 4

Digital Collections @ Dordt Dordt Canon University Publications 1973 The Canon, [1972-73]: Volume 3, Number 4 Dordt College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.dordt.edu/dordt_canon Recommended Citation Dordt College, "The Canon, [1972-73]: Volume 3, Number 4" (1973). Dordt Canon. 55. https://digitalcollections.dordt.edu/dordt_canon/55 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at Digital Collections @ Dordt. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dordt Canon by an authorized administrator of Digital Collections @ Dordt. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Soli Deo Gloria CANNON DORDT COLLEGE, SIOUX CENTER, IOWA VOL. III -.- No.4 Mother Night: Victims of Change Victoria and Blue·Jeans Prof. James Koldenhoven by Pat De Young What Is Life? The old and the new, like jaws of a trap, have closed on the people of I saw Victoria Allison for the first ally she disagreed in discussion-too by Becky Maatman Tennessee Williams and John Osborne's time on satge. She walked out, long loudly in her curt, clipped Yankee ac- Vonnegut, author of Mother Night plays, The Glass Menagerie and Look swinging steps, took the mike, and cent. Having said what she wanted to asks, "What is a war criminal? Is it Back inAnger. Laura Wingfield iS1he quietly announced, "I will sing a selec- say, she would give her head a toss someone who has obeyed his conscience, central victim in Williams' American tion from Hair." Staring at the floor in and return to silence, eyes focused on perhaps doing wrong,",» is it someone (U.S.A.) culture in the 1930's and silence, she paused. -

Elements of Gallows Humor in Vonnegut's Slaughter House Five

Journal of Literature, Languages and Linguistics www.iiste.org ISSN 2422-8435 An International Peer-reviewed Journal Vol.41, 2018 Elements of Gallows Humor in Vonnegut's Slaughter House Five Negar Khodabandehloo M.A. Student of Payame Noor University, Arak Branch, Iran Mojgan Eyvazi Assistant professor, English Department,Payam-e-Noor University, Tehran, Iran Abstract This study analyzes the outstanding satirist Kurt Vonnegut's novel Slaughter-house-five to demonstrate how the elements of Gallows Humor are applied to provide a better understanding of the author's worldview and of his narrative process. This is an anti-war book in which Vonnegut has attempted to blend the serious theme with humor. Through the choice of his protagonist- Billy Pilgrim- and the manipulation of black humor, Vonnegut exposes the atrocities of war from a new viewpoint. The focal point is to extract the phrases containing gallows humor, a sort of black humor, to be studied and explained by details, accordingly some literary terms are to be precisely defined and the unique style of writing is indispensable. Keywords: Anti-war, Black Humor, Gallows Humor, Satire, Humor, Vonnegut 1. Introduction Gallows humor is a kind of black humor in which the threatened person witnesses the oppression. As the name represents, the person threatened is implicated with no hope and no way to escape from the disaster. The misfortune is obvious to him, and he prefers joking about it instead of feeling sorrow. This section includes a definition of the gallows humor followed by some examples for more clarifications. In an essay posted on the website of the Philosophy Club, which meets regularly in Santa Monica, CA. -

CAT's CRADLE by Kurt Vonnegut

CAT'S CRADLE by Kurt Vonnegut Copyright 1963 by Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. Published by DELL PUBLISHING CO., INC., 1 Dag Hammarskjold Plaza, New York, N.Y. 10017 All rights reserved. ISBN: 0-440-11149-8 For Kenneth Littauer, a man of gallantry and taste. Nothing in this book is true. "Live by the foma* that makes you brave and kind and healthy and happy." --The Books of Bokonon. 1:5 *Harmless untruths contents 1. The Day the World Ended 2. Nice, Nice, Very Nice 3. Folly 4. A Tentative Tangling of Tendrils 5. Letter from a Pie-med 6. Bug Fights 7. The Illustrious Hoenikkers 8. Newt's Thing with Zinka 9. Vice-president in Charge of Volcanoes 10. Secret Agent X-9 11. Protein 12. End of the World Delight 13. The Jumping-off Place 14. When Automobiles Had Cut-glass Vases 15. Merry Christmas 16. Back to Kindergarten 17. The Girl Pool 18. The Most Valuable Commodity on Earth 19. No More Mud 20. Ice-nine 21. The Marines March On 22. Member of the Yellow Press 23. The Last Batch of Brownies 24. What a Wampeter Is 25. The Main Thing About Dr. Hoenikker 26. What God Is 27. Men from Mars 28. Mayonnaise 29. Gone, but Not Forgotten 30. Only Sleeping 31. Another Breed 32. Dynamite Money 33. An Ungrateful Man 34. Vin-dit 35. Hobby Shop 36. Meow 37. A Modem Major General 38. Barracuda Capital of the World 39. Fata Morgana 40. House of Hope and Mercy 41. A Karass Built for Two 42. -

Being in the Early Novels of Kurt Vonnegut

A MORAL BEING IN AN AESTHETIC WORLD: BEING IN THE EARLY NOVELS OF KURT VONNEGUT BY JAMES HUBBARD A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS English May 2015 Winston-Salem, North Carolina Approved By: James Hans, Ph.D., Advisor Barry Maine, Ph.D., Chair Jefferson Holdridge, Ph.D. Table of Contents Table of Contents ii Abstract iii Chapter 1: Introduction 1 Chapter 2: Being Thrown 7 Chapter 3: Being as a Happening of Truth 27 Chapter 4: Projecting the Poetry of Being 47 References 53 Curriculum Vitae 54 ii Abstract In this this paper I will address notions of being in four of Kurt Vonnegut’s novels using Martin Heidegger’s aesthetic phenomenology. The four novels that this paper will address are Player Piano, Sirens of Titan, Slaughterhouse-Five, and Breakfast of Champions. Player Piano and Sirens of Titan are Vonnegut’s first two novels, and they approach being in terms of what Heidegger referred to as “throwness.” These initial inquiries into aspects of existence give way to a fully developed notion of being in Slaughterhouse-Five and Breakfast of Champions. These novels are full aware of themselves has happenings of truth containing something of their author’s own being. Through these happenings, Vonnegut is able to poetically project himself in a way that not only reveals his own being, but also serves as a mirror that can reveal the being of those reflected in it. iii Chapter 1: Introduction Kurt Vonnegut’s literary significance is due, at least in part, to the place that he has carved out for himself in popular culture. -

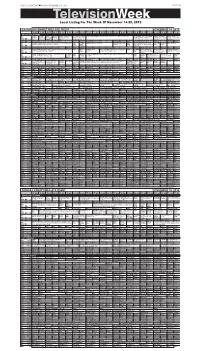

Televisionweek Local Listing for the Week of November 14-20, 2015

PRESS & DAKOTAN n FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 13, 2015 PAGE 9B TelevisionWeek Local Listing For The Week Of November 14-20, 2015 SATURDAY PRIMETIME/LATE NIGHT NOVEMBER 14, 2015 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 BROADCAST STATIONS Cook’s Victory Prairie America’s Classic Gospel Songs The Lawrence Welk High School Football SDHSAA Class 11AAA, Final: Teams TBA. (N) (Live) Rock Garden Tour: Soul Butter Austin City Limits Globe Trekker The PBS Country Garden’s Yard and Heartlnd of patriotism and Show California vaca- and Hogwash (In Stereo) Å “James Taylor” (N) (In history of tea; cultural KUSD ^ 8 ^ Å Garden faith. Å tion destinations. Stereo) Å traditions. KTIV $ 4 $ College Football Wake Forest at Notre Dame. (N) Å News 4 Insider Dateline NBC (In Stereo) Å Saturday Night Live News 4 Saturday Night Live (N) Å Extra (N) Å 1st Look House College Football Wake Forest at Notre Dame. From Notre Dame Sta- KDLT The Big Dateline NBC (In Stereo) Å Saturday Night Live KDLT Saturday Night Live Elizabeth The Simp- The Simp- KDLT News Å NBC dium in South Bend, Ind. (N) (In Stereo Live) Å News Bang (In Stereo) Å News Banks; Disclosure performs. (N) (In sons sons KDLT % 5 % (N) Å Theory (N) Å Stereo) Å KCAU ) 6 ) College Football Michigan at Indiana. (N) (Live) Score News Edition College Football Oklahoma at Baylor. -

Vonnegut's Criticisms of Modern Society Candace Anne Strawn Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1972 Vonnegut's criticisms of modern society Candace Anne Strawn Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the American Literature Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Strawn, Candace Anne, "Vonnegut's criticisms of modern society" (1972). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 34. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/34 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ---~- ~--~-~- - Vonnegut's criticisms of modern society by Candace Anne Strawn A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: English Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1972 ii. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. SOME PERSPECTIVES OF MODERN SOCIETY 1 II. IRRATIONALITY OF HUMAN BEHAVIOR 19 III. DEHUMANIZATION OF THE INDIVIDUAL 29 IV. MAN'S INHUMANITY TO MAN 37 v. CONCLUSION 45 VI. A SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY 48 1 I. SOME PERSPECTIVES OF MODERN SOCIETY In his age-old effort to predict the future, man has tried many methods, including a careful study of past history. Although the act of predicting social events is largely theoretical--since it is necessarily a tentative process--numerous historians, sociologists, theologians, scientists, and artists persist in discovering trends or seeing patterns in the movement of history. -

Harrison Bergeron," Which First Appeared in Fantasy Ture Or a Pretty Face, Would Feel Like Something the Cat Drug In

KURT VONNEGUT JR. Harrison Ber;geron The year was 2081, and everybody was finally equal. They weren't only equal before God and the law. They were equal every which way. Nobody [Curt Vonnegut Jr. (b. 1922) was born on November 11 in Indianapolis, Indi ana. The son ofan architect and a homemaker, he attended Cornell University was smarter than anybody else. Nobody was better looking than anybody and Carnegie Mellon University before the outbreak ofWorld War II, when he else. Nobody was stronger or quicker than anybody else. All this equality interrupted his studies to serve in the U.S. Army. As aprisoner ofwar in Dres was due to the 211th, 212th, and 213th Amendments to the Constitu den, Germany, he survived a devastating air raid on February 13, 1945, by tion, and to the unceasing vigilance of agents of the United States Handi staying in a meat locker under a slaughterhouse during the bombing. After capper General. World War II, Vonnegut worked in public relations at the General Electric Com Some things about living still weren't quite right, though. April, for pany in Schenectady, New York, before becoming a freelance writer. Player instance, still drove people crazy by not being springtime. And it was in Piano, his first novel, appeared in 1952, followed by a second fantasy novel, that clammy month that the H-G men took George and Hazel Bergeron's The Sirens of Titan, in 1959. Two years later he published Mother Night, a fourteen-year-old son, Harrison, away. first-person fictional narrative about World War II.