Early and Middle Childhood: Changing Patterns for Learning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. University Microfilms International A Beil & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. -

Bohemian Space and Countercultural Place in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury Neighborhood

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2017 Hippieland: Bohemian Space and Countercultural Place in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury Neighborhood Kevin Mercer University of Central Florida Part of the History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Mercer, Kevin, "Hippieland: Bohemian Space and Countercultural Place in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury Neighborhood" (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 5540. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/5540 HIPPIELAND: BOHEMIAN SPACE AND COUNTERCULTURAL PLACE IN SAN FRANCISCO’S HAIGHT-ASHBURY NEIGHBORHOOD by KEVIN MITCHELL MERCER B.A. University of Central Florida, 2012 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term 2017 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the birth of the late 1960s counterculture in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury neighborhood. Surveying the area through a lens of geographic place and space, this research will look at the historical factors that led to the rise of a counterculture here. To contextualize this development, it is necessary to examine the development of a cosmopolitan neighborhood after World War II that was multicultural and bohemian into something culturally unique. -

![The Canon, [1972-73]: Volume 3, Number 4](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9514/the-canon-1972-73-volume-3-number-4-649514.webp)

The Canon, [1972-73]: Volume 3, Number 4

Digital Collections @ Dordt Dordt Canon University Publications 1973 The Canon, [1972-73]: Volume 3, Number 4 Dordt College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.dordt.edu/dordt_canon Recommended Citation Dordt College, "The Canon, [1972-73]: Volume 3, Number 4" (1973). Dordt Canon. 55. https://digitalcollections.dordt.edu/dordt_canon/55 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at Digital Collections @ Dordt. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dordt Canon by an authorized administrator of Digital Collections @ Dordt. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Soli Deo Gloria CANNON DORDT COLLEGE, SIOUX CENTER, IOWA VOL. III -.- No.4 Mother Night: Victims of Change Victoria and Blue·Jeans Prof. James Koldenhoven by Pat De Young What Is Life? The old and the new, like jaws of a trap, have closed on the people of I saw Victoria Allison for the first ally she disagreed in discussion-too by Becky Maatman Tennessee Williams and John Osborne's time on satge. She walked out, long loudly in her curt, clipped Yankee ac- Vonnegut, author of Mother Night plays, The Glass Menagerie and Look swinging steps, took the mike, and cent. Having said what she wanted to asks, "What is a war criminal? Is it Back inAnger. Laura Wingfield iS1he quietly announced, "I will sing a selec- say, she would give her head a toss someone who has obeyed his conscience, central victim in Williams' American tion from Hair." Staring at the floor in and return to silence, eyes focused on perhaps doing wrong,",» is it someone (U.S.A.) culture in the 1930's and silence, she paused. -

Tripping with Stephen Gaskin: an Exploration of a Hippy Adult Educator

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Spring 5-2012 Tripping With Stephen Gaskin: An Exploration of a Hippy Adult Educator Gabriel Patrick Morley University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Adult and Continuing Education Administration Commons, Civic and Community Engagement Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Curriculum and Social Inquiry Commons, Educational Methods Commons, and the Educational Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Morley, Gabriel Patrick, "Tripping With Stephen Gaskin: An Exploration of a Hippy Adult Educator" (2012). Dissertations. 808. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/808 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi TRIPPING WITH STEPHEN GASKIN: AN EXPLORATION OF A HIPPY ADULT EDUCATOR by Gabriel Patrick Morley Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Education May 2012 ABSTRACT TRIPPING WITH STEPHEN GASKIN: AN EXPLORATION OF A HIPPY ADULT EDUCATOR by Gabriel Patrick Morley May 2012 For the last 40 years, Stephen Gaskin has been an adult educator on the fringe, working with tens of thousands of adults in the counterculture movement in pursuit of social change regarding marijuana legalization, women’s rights, environmental justice issues and beyond. Gaskin has written 11 books about his experiences teaching and learning with adults outside the mainstream, yet, he is virtually unknown in the field of adult education. -

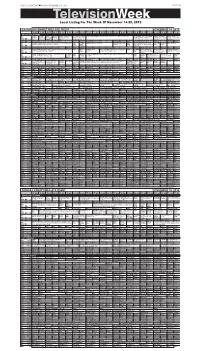

Televisionweek Local Listing for the Week of November 14-20, 2015

PRESS & DAKOTAN n FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 13, 2015 PAGE 9B TelevisionWeek Local Listing For The Week Of November 14-20, 2015 SATURDAY PRIMETIME/LATE NIGHT NOVEMBER 14, 2015 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 BROADCAST STATIONS Cook’s Victory Prairie America’s Classic Gospel Songs The Lawrence Welk High School Football SDHSAA Class 11AAA, Final: Teams TBA. (N) (Live) Rock Garden Tour: Soul Butter Austin City Limits Globe Trekker The PBS Country Garden’s Yard and Heartlnd of patriotism and Show California vaca- and Hogwash (In Stereo) Å “James Taylor” (N) (In history of tea; cultural KUSD ^ 8 ^ Å Garden faith. Å tion destinations. Stereo) Å traditions. KTIV $ 4 $ College Football Wake Forest at Notre Dame. (N) Å News 4 Insider Dateline NBC (In Stereo) Å Saturday Night Live News 4 Saturday Night Live (N) Å Extra (N) Å 1st Look House College Football Wake Forest at Notre Dame. From Notre Dame Sta- KDLT The Big Dateline NBC (In Stereo) Å Saturday Night Live KDLT Saturday Night Live Elizabeth The Simp- The Simp- KDLT News Å NBC dium in South Bend, Ind. (N) (In Stereo Live) Å News Bang (In Stereo) Å News Banks; Disclosure performs. (N) (In sons sons KDLT % 5 % (N) Å Theory (N) Å Stereo) Å KCAU ) 6 ) College Football Michigan at Indiana. (N) (Live) Score News Edition College Football Oklahoma at Baylor. -

Manhood in the Age of Aquarius | Chapter 5

Manhood in the Age of Aquarius Chapter 5 Tim Hodgdon Chapter 5 "We Here Work as Hard as We Can": The Farm's Sexual Division of Labor In the spring of 1975, Patricia Mitchell, her preschool son, and her lover, Don 1 Lapidus, arrived at the entrance to The Farm, hoping to join. They had read about the burgeoning commune in its book-length recruitment brochure, Hey, Beatnik, and after much discussion, had packed their possessions in their car. At the front gate, a man with a clipboard described the hippie village as a monastery of householder yogis where Stephen Gaskin's teachings guided daily labor and family life. Gaskin's students, he said, agreed to live together nonviolently, to consume a strictly vegan diet, and to hold all money and property in common. After some time at the gate, the three were admitted as "soakers," soaking up the new life that was The Farm.1 A member of the gate crew drove the new soakers to their host households. The 2 Mitchell-Lapidus trio were welcomed into a structure consisting of a large army tent (recall the frame–and–canvas structures in the television comedy M*A*S*H) flanked by two Caravan-vintage school buses, where twelve people made their home. For the duration of their time as soakers, the family slept on a couch in the tent.2 They arrived in time to help with preparations for dinner. Patricia joined women in the kitchen area of the tent, washing potatoes from the previous year's harvest.3 Over dinner, their hosts reminisced about The Farm's beginnings. -

The 6Os Communes Messianic Communities) Bus at Bellows Falls) Vermont

The 6os Communes Messianic Communities) bus at Bellows Falls) Vermont. Photograph by Timothy Miller. TIMOTHY MILLER The 60s Communes Hippies and Beyond Syracuse UniversityPress Copyright © 1999 by Syracuse UniversityPress, Syracuse, New York 13244-5160 AllRights Reserved First Edition 1999 02 03 04 05 06 6 5 4 3 2 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard forInformation Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANS I z39.48-1984.@ LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOG ING -IN-PUBLICATI ON DATA Miller, Timothy, 1944- The 6os communes : hippies and beyond/ Timothy Miller. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8156-2811-0 (cloth: alk. paper) ISBN 0-8156-0601-x (pbk.: alk. paper) I. Communal living-United States. 2. United States-Social conditions- 1960-1980. I. Title. II. Title: Sixties communes. III. Title: Hippies and beyond. HQ97I.M55 1999 307.77'4'0973-dc21 99-37768 Manufactured in the United States of America For Michael) Gretchen) andJeffre y TIMOTHY MILLER is professor of religious studies at the University of Kansas. Among his previous publica tions is The Quest forUt opia in Twentieth-CenturyAm erica: 1900-1960) the first of three volumes on communal life to be published by Syracuse UniversityPress. Contents Acknowledgments IX Introduction xm I. Set and Setting: The Roots of the 196os-Era Communes I 2. The New Communes Emerge: 1960-1965 17 3. Communes Begin to Spread: 1965-1967 41 4. Out of the Haight and Back to the Land: Countercultural Communes after the Summer of Love 67 5. Searching for a Common Center: Religious and Spiritual Communes 92 6. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type o f computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy subm itted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back o f the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced withwith permissionpermission ofof the the copyrightcopyright owner. owner. Further Further reproduction reproduction prohibited prohibited without without permission. -

Kurt Vonnegut Jr. Confronts the Death of the Author Justin Philip Mayerchak Florida International University, [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DigitalCommons@Florida International University Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 4-1-2016 Kurt Vonnegut Jr. Confronts the Death of the Author Justin Philip Mayerchak Florida International University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Mayerchak, Justin Philip, "Kurt Vonnegut Jr. Confronts the Death of the Author" (2016). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2440. http://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/2440 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida KURT VONNEGUT JR. CONFRONTS THE DEATH OF THE AUTHOR A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTERS OF ARTS in ENGLISH by Justin Philip Mayerchak 2016 To: Dean Michael R. Heithaus College of Arts, Sciences and Education This thesis, written by Justin Philip Mayerchak, and entitled Kurt Vonnegut Jr. Confronts the Death of the Author, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this thesis and recommend that it be approved. _______________________________________ Bruce Harvey _______________________________________ Ana Lusczynka _______________________________________ Nathaniel Cadle, Major Professor Date of Defense: April 1, 2016 The thesis of Justin Philip Mayerchak is approved. -

Thesewaneepurplev179n8021800.Pdf (839.6Kb)

1 etoanee Burpte Vol. CLXXVIII No. 8 TENNESSEE. FEBRUARY 18. 2000 UNIVERSITY OF THE SOUTH SEWANEE. Sewanee History: An African You Little Shrimp American's Perspective u, DoagtoWMtrmu Wriiet h hruan S. Mi Jo On I enlightened studenl ,eph i ajan ' 1 w>* an African ,i into lift foi during thi ri, an in Sewanei i •I 1930 1970 Vwan ingofl African American nostalgicall) ol Month i ujan spoke well as hisSi as A the militar) ><> hi i tijanthen ,,, Vl lopmeni Mi i ., questions fromthi withra audience dealing primaril) ai Sewanei Popl i ial issues discussion ranged from life in i to the i" an Lu|an in his days at the Ku Klux Klan in this Joseph Sowanee. Lu|ans speech i n i Awareness phi ujani ami toSi wane* in opened African Missouri v- i,,, m M i ouis Month. hi worked in the home Pholo By Elizabeth Ogletree ayoungman had I nlon rheatn indt - The Sewanei ol Vlc« Chancell twodlffen m mowings 1 Utai graduating from Win Guerr) and thi attended the 00 ihowing hool hewasdrafted people wi n allowed n 1943 Previously, colored Spring BreakOutreach Trip. inW the Nav) in towards the Honduras ,,. 10:00 shov ,„ \i,,, an American could onl) itlon iteward,acooi 01 ..baker going to the colored re< died aboui whites forces I ujan in the armed colored ihowing During this tim( Until Fall 2000 regulation was changed Suspended thai this in Epsilon allowed to e II Phi Kappa draft d people wi rt not around the time thai lw was ... .u . ...,r.i. -

AIMS Pays Tribute to Stephen Gaskin & Mary Ann Cahill

Page 1 of 2 AIMS pays tribute to Stephen Gaskin & Mary Ann Cahill • aims.org.uk AIMS pays tribute to Stephen Gaskin & Mary Ann Cahill AIMS Journal 2014, Vol 26 No 4 Stephen Gaskin AIMS was saddened to hear of the death of Stephen Gaskin (16 February 1935 – 1 July 2014) in July. Stephen was the husband of our sister, long-term AIMS supporter and protector of women’s birthing rights, Ina May Gaskin. Together with a small group of like-minded activists in 1970, Stephen and Ina May founded The Farm, a spiritual intentional community in Summertown, Tennessee with an international reputation for spiritual, woman-centred midwifery with unrivalled outcomes. Stephen was a prominent American counterculture icon and self-labelled professional Hippie. He was a freethinker, author of over a dozen books, a political activist and a philanthropic organiser. He was also an acclaimed speaker on magic, energy, life in community and service to humanity. On his leadership of The Farm, he famously said: ‘I'm a teacher, not a leader. If you lose your leader, you’re leaderless and lost, but if you lose your teacher there’s a chance that he taught you something and you can navigate on your own.’ He was possibly most well known in the UK as US Green Party presidential primary candidate in 2000, with a manifesto including campaign finance reform, universal healthcare, and decriminalisation of marijuana. AIMS sends our condolences to Ina May and to the rest of Stephen’s family, friends and community. Mary Ann Cahill AIMS also pays tribute to Mary Ann Cahill (10 June 1927 – 26 October 2014), one of the seven founders of La Leche League. -

Follow Us on Facebook & Twitter @Back2past for Updates

1/30 - Golden to Modern Age Comics & Batman Collectibles 1/30/2021 This session will be begin closing at 6PM on 01/30/20, so be sure to get those bids in via Proxibid! Follow us on Facebook & Twitter @back2past for updates. Visit our store website at GOBACKTOTHEPAST.COM or call 313-533-3130 for more information! Get the full catalog with photos, prebid and join us live at www.proxibid.com/backtothepast! See site for full terms. LOT # QTY LOT # QTY 1 Auction Rules 1 15 Bat(h) Time Fun Batman Lot 1 All new condition. Towels, bath mat, crazy foam, and more! You 2 Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles #4 (1985) 1 Key first printing!! NM- condition. get all pictured. 3 Batman Black and White Statue/Neal Adams 1 16 Daredevil #176 Key/1st Stick 1 #546/3500. Approximately 6.75" tall. Opened only for inspection First appearance of Stick. NM- condition. and to photograph. 17 Daredevil #173 Frank Miller 1 Frank Miller Daredevil. VF+ condition. 4 Star Wars #4 (Marvel) 1977 1st Print 1 Part 4 of the A New Hope adaptation. VF condition. 18 The Mighty Crusaders #5 (1965) 1 From The Mighty Comics Group. VG+ condition. 5 Iron Man Vol. 3 #14 CGC 9.8 1 CGC graded comics. Fantastic Four appearance. 19 Daredevil #163 Hulk Cover/Frank Miller 1 Frank Miller Daredevil. VF- condition. 6 Dark Knight Returns Golden Child (x6) 1 Lot of (6) One-shot by Frank Miller set in the future timeline of The 20 Freedom Fighters Lot of (3) DC Bronze 1 Dark Knight Returns.