William H. Barton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Growing in Faith

GROWING IN FAITH CALIFORNIA COUNCIL ON AMERICAN-ISLAMIC RELATIONS - CALIFORNIA The Council on American-Islamic Relations is the largest American Muslim civil rights and advocacy organization in the United States. CAIR-California is the organization’s largest and oldest chapter, with offices in the Greater Los Angeles Area, the Sacramento Valley, San Diego and the San Francisco Bay Area. OUR VISION | To be a leading advocate for justice and mutual understanding. OUR MISSION | To enhance understanding of Islam, encourage dialogue, protect civil liberties, empower American Muslims and build coalitions that promote justice and mutual understanding. For questions about this report, or to obtain copies, contact: Council on American-Islamic Relations Council on American-Islamic Relations San Francisco Bay Area (CAIR-SFBA) Sacramento Valley (CAIR-SV) 3000 Scott Blvd., Suite 101 717 K St., Suite 217 Santa Clara, CA 95054 Sacramento, CA 95814 Tel: 408.986.9874 Tel: 916.441.6269 Fax: 408.986.9875 Fax: 916.441.6271 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Council on American-Islamic Relations Council on American-Islamic Relations Greater Los Angeles Area (CAIR-LA) San Diego (CAIR-SD) 2180 W. Crescent Ave., Suite F 8316 Clairemont Mesa Blvd., Suite 203 Anaheim, CA 92801 San Diego, CA 92111 Tel: 714.776.1847 Tel/Fax: 858.278.4547 Fax: 714.776.8340 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] FAIR USE NOTICE: This report may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. It is being made available in an effort to advance the understanding of political, human rights, democracy and social justice issues. -

U.S. Muslim Charities and the War on Terror

U.S. Muslim Charities and the War on Terror A Decade in Review December 2011 Published: December 2011 by The Charity & Security Network (CSN) Front Cover Photo: Candice Bernd / ZCommunications (2009) Demonstrators outside a Dallas courtroom in October 2007during the Holy Land Foundation trial. Acknowledgements: Supported in part by a grant from the Open Society Foundation, Cordaid, the Nathan Cummings Foundation, Moriah Fund, Muslim Legal Fund of America, Proteus Fund and an Anonymous donor. We extend our thanks for your support. Written by Nathaniel J. Turner, Policy Associate, Charity & Security Network. Edited by Kay Guinane and Suraj K. Sazawal of the Charity & Security Network. Thanks to Mohamed Sabur of Muslim Advocates and Mazen Asbahi of the Muslim Public Affairs Council for reviewing the report, which benefitted from their suggestions. Any errors are solely those of CSN, not the reviewers. The Charity & Security Network is a network of humanitarian aid, peacebuilding and advocacy organizations seeking to eliminate unnecessary and counterproductive barriers to legitimate charitable work caused by current counterterrorism measures. Charity & Security Network 110 Maryland Avenue, Suite 108 Washington, D.C. 20002 Tel. (202) 481-6927 [email protected] www.charityandsecurity.org Table of Contents Executive Summary............................................................................................................................................ 3 Introduction......................................................................................................................................................... -

Download Legal Document

Case 2:17-cv-02132-RBS Document 50 Filed 03/14/19 Page 1 of 53 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA _________________________________________ : XIAOXING XI, et al., : : Plaintiffs, : CIVIL ACTION : v. : No. 17-cv-2132 : FBI SPECIAL AGENT ANDREW HAUGEN, et : JURY TRIAL DEMANDED al., : : : Defendants. : _________________________________________ : NOTICE OF SUPPLEMENTAL AUTHORITY In further support of their Opposition to the Official Capacity Defendants’ Motion to Dismiss the Complaint (ECF No. 42), Plaintiffs Xiaoxing Xi, Qi Li, and Joyce Xi (“Plaintiffs”) respectfully submit the attached opinion by the Ninth Circuit in Fazaga v. FBI, No. 12-56867, 2019 WL 961953 (9th Cir. Feb. 28, 2019). As Plaintiffs have explained, the government’s ongoing retention and searching of their personal data and communications establishes their standing to pursue declaratory and injunctive relief. See Pls.’ Opp. to Gov’t Officials’ MTD 11- 17. The Ninth Circuit’s decision in Fazaga directly supports Plaintiffs’ standing. In Fazaga, the plaintiffs alleged that the FBI conducted an unlawful, covert surveillance program that gathered information about Muslims based on their religious identity. 2019 WL 961953, at *3. In addition to other relief, the plaintiffs sought the expungement of all information obtained or derived through the program and maintained by the government. Id. at *28-29. The government defendants argued that expungement was not available because the plaintiffs “advance[d] no plausible claim of an ongoing constitutional violation.” Id. at *29. Specifically, Case 2:17-cv-02132-RBS Document 50 Filed 03/14/19 Page 2 of 53 the defendants contended that “[e]ven if the government’s past conduct violated the Constitution, the continued maintenance of records . -

Alifornia R a Yer Oca Tions

CALIFORNIA PRAYER LOCATIONS SAN JOSE NORTHERN CALIFORNIA 222-6686, *80E*580E*205*5N*120 LIGHTHOUSE MOSQUE SOUTH BAY ISLAMIC ASSOCIATION Directions Start From SF Bay Bridge (Hwy 80) E*99S*Shaw Ex R* www.masjidfresno.org 4606 Martin Luther King Jr Way, Oakland, 325 N 3rd St, San Jose, 95112, 408-947- BADR ISLAMIC CENTER 94609,80E*580E*CA 24E*R Martin Luther 9389, 101S*Julian Ex R*3rd R* www.sbia.net ALAMEDA 4222 W. Alamos # 101, Fresno, 93722, 559- KingU to 52nd www.lighthousemosque.org EVERGREEN ISLAMIC CENTER MASJID QUBA 274-0906, 80E*580E*205*5N*120 E- JAMAATUS SAALAM 2486 Ruby Ave. San Jose, 95143, 408-239- 707 Haight Ave, Alameda, 94501, 510-337- Manteca *99S*Shaw W Ex R*R N El 1515 Mac Arthur Bl, Oakland, 94602, 510- 6668, 101S*Capital Expressway East* L 1277, 80E*980S*Jackson Ex L*8th Capitan*L W Alamos* www.masjidbadr.com 530-3272, 80E*580E*Ex 22 Park*L 33 St*L Tully *R Ruby* www.sbia.net/Ruby.html L*Webster L*Haight MASJID AL-AQABA 14 Av*R Mac Arthur BLOSSOM VALLEY MUSLIM COMM. ISLAMIC CENTER OF ALAMEDA 1528 Kern St.Fresno, 93706, 559-495-1606 PALO ALTO CENTER 901 Santa Clara Av., Alameda, 94501, 510- *80E*580*205*5N*120E*99S* Ex132B STANFORD UNIV INTERNATIONAL CTR 5885 Santa Teresa Blvd. # 113, San Jose, 748-9052, 80E*880S*5th St Ex*L Fresno St.L. 590 Old Union Club House,#19, 3rd floor, 95123, 408-362-0903, 408-568-6926* Broadway*R Webster *L HANFORD Palo Alto, 94305, 101 S* Embarcadero W 101S*Guadalupe Pkwy CA87* CA87S Constitution Way*Lincoln MASJID HANFORD Ex*El Camino L* Campus R*to Santa Teresa L*Santa Teresa Blvd Ex R*www.bvmcc.net L*R 9th* Santa Clara R* 308 S 10th Ave, Hanford, 93230, 559-583- L*590 Bldg* www.stanford.edu/group/ISSU ISLAMIC COMM. -

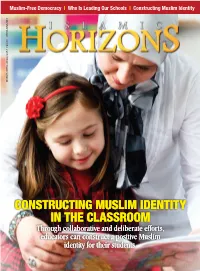

Constructing Muslim Identity

Muslim-Free Democracy | Who Is Leading Our Schools | Constructing Muslim Identity MARCH/APRIL 2016/1437 | $4.00 WWW.ISNA.NET CONSTRUCTING MUSLIM IDENTITY IN THE CLASSROOM Through collaborative and deliberate efforts, educators can construct a positive Muslim identity for their students. CONTENTS VOL 45 NO. 2 MARCH/APRIL 2016 visit isna online at: WWW.ISNA.NET EDUCATION 21 Leading Initiatives 24 Who Is Leading Our Schools? 26 W hy do Islamic School Teachers Drop Out? 30 C onstructing Muslim Identity in the Classroom 32 Islamic Schools vs. Public Schools 36 Why We Need Diverse Books 38 Envisioning Authentic Islamic Schools 40 T he Role Schools Can Play in 21 Constructing a Muslim Identity HEALTH & WELL-BEING 42 Ethical Decision Making and the Muslim Patient 44 Overcoming Stigma ISLAM IN AMERICA 46 Equally Empowered 48 Standing with Muslims 46 MUSLIMS IN ACTION 50 Seeds of Progress FINANCE 52 The Islamic Law of Inheritance SPECIAL FEATURE 54 Yes, Islam Really is a Religion THE MUSLIM WORLD 52 56 Muslim-Free Democracy FAMILY LIFE DEPARTMENTS 58 Embodying Care and Mercy 6 Editorial 8 ISNA Matters 10 Community Matters 60 New Releases DESIGN & LAYOUT BY: Gamal Abdelaziz, A-Ztype Copyeditor: Jay Willoughby. The views expressed in Islamic Horizons are not necessarily the views of its editors nor of the Islamic Society of North America. Islamic Horizons does not accept unsolicitated articles or submissions. All references to the Quran made are from 58 The Holy Quran: Text, Translation and Commentary, Abdullah Yusuf Ali, Amana, Brentwood, MD. ISLAMIC HORIZONS MARCH/APRIL 2016 5 EDITORIAL Teaching with a Heart PUBLISHER The Islamic Society of North America (ISNA) PRESIDENT is heartening TO note that some enjoys respect among teachers and Azhar Azeez SECRETARY GENERAL schools are moving from “teaching to school administrators with its Edu- Hazem Bata the test” to using “teaching the whole cation Forum, which is now in its 17th child” approach. -

Fazagacomplaint.Pdf

1 MARTINEZ, ASSISTANT DIRECTOR 2 IN CHARGE, FEDERAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION’S LOS ANGELES 3 DIVISION, in his official capacity; J. 4 STEPHEN TIDWELL; BARBARA WALLS; PAT ROSE; KEVIN 5 ARMSTRONG; PAUL ALLEN; Does 6 1-20 7 Defendants. 8 9 Additional Plaintiffs’ Attorneys: 10 Dan Stormer (SBN 101967) 11 [email protected] Joshua Piovia-Scott (SBN 22364) 12 [email protected] 13 Reem Salahi (SBN 259711) [email protected] 14 HADSELL STORMER KEENY RICHARDSON & RENICK, LLP 15 128 N. Fair Oaks Avenue, Suite 204 Pasadena, California 91103 16 Telephone: (626) 585-9600 17 Facsimile: (626) 577-7079 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 1 PRELIMINARY STATEMENT 2 1. This case concerns an FBI-paid agent provocateur who, by 3 misrepresenting his identity, infiltrated several mainstream mosques in Southern 4 California, based on the FBI’s instructions that he gather information on Muslims. 5 2. The FBI then used him to indiscriminately collect personal 6 information on hundreds and perhaps thousands of innocent Muslim Americans in 7 Southern California. Over the course of fourteen months, the agents supervising 8 this informant sent him into various Southern California mosques, and through his 9 surveillance gathered hundreds of phone numbers, thousands of email addresses, 10 hundreds of hours of video recordings that captured the interiors of mosques, 11 homes, businesses, and the associations of hundreds of Muslims, thousands of 12 hours of audio recording of conversations — both where he was and was not 13 present — as well as recordings of religious lectures, discussion groups, classes, 14 and other Muslim religious and cultural events occurring in mosques. -

Brief in Opposition

No. 20-828 IN THE Supreme Courtd of the United States FEDERAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION, ET AL., Petitioners, —v.— YASSIR FAZAGA, ET AL., Respondents. ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT BRIEF IN OPPOSITION Dan Stormer Ahilan Arulanantham Shaleen Shanbhag Counsel of Record HADSELL STORMER RENICK UCLA SCHOOL OF LAW & DAI LLP 385 Charles Young Drive East 128 North Fair Oaks Avenue Los Angeles, CA 90095 Pasadena, CA 91103 (310) 825-1029 [email protected] Amr Shabaik Dina Chehata Peter Bibring CAIR-LOS ANGELES Mohammad Tajsar 2180 W. Crescent Avenue, ACLU FOUNDATION OF Suite F SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA Anaheim, CA 92801 1313 West Eighth Street Los Angeles, CA 90017 QUESTION PRESENTED This case challenges a domestic FBI surveillance program that, according to the FBI’s own informant, targeted individuals for electronic surveillance because of their religion. The Government asserted the state secrets privilege and sought dismissal of Respondents’ free exercise and religious discrimination claims on that basis. The court of appeals held that, with respect to electronic surveillance collected as part of the investigation, the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act provides for ex parte and in camera review of the lawfulness of the surveillance, and that procedure displaces, at least at the threshold, the rule permitting dismissal of a claim based on state secrets. The question presented is: Whether the state secrets evidentiary privilege recognized in Reynolds v. United States authorizes the dismissal of claims challenging the lawfulness of electronic surveillance, particularly where Section 1806(f) of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA), 50 U.S.C. -

2008 Ramadan Issue

THE ISLAMIC BULLETIN VOL. X, NO. 23 SPECIAL RAMADAN ISSUE Ramadan Mubarak ! IN THIS ISSUE The Islamic Bulletin returns with our Ramadan edition! We are happy to introduce our recently launched and greatly expanded website, with the LETTERS TO THE EDITOR ............................... 2 resources you need and in the language of your choice—English, Spanish, French, German, Italian, and Arabic. We have everything from free downloads of classic Islamic Books to the Masjid and Qibla Finder, which points the way ISLAMIC WORLD NEWS .............................. 4 from a satellite map of your neighborhood! Want to hear live radio Quran? Do you need to learn how to pray? Thinking of making a last will? We have them PIONEER OF THE ENVIRONMENT ..................... 5 all, and so much more. Please visit our website at www.islamicbulletin.org, and click on “Enter Here”, where you will find our site to be user-friendly with MADRASSA AN-NOOR FOR THE BLIND ............ 7 easy-find icons. HOW I EMBRACED ISLAM ............................ 8 First and foremost, our goal as Muslims is to worship Allah. We all come from different backgrounds and cultures. Yet, the one strong common thread WHAT COULD YOU GAIN FROM FASTING? ..... 11 between each and every one of us is our religion, Islam. So, instead of finding the differences that divide us, let us look at and celebrate the similarities that AFTER RAMADAN ....................................... 12 unite us. And since the one big thing that unites us is Islam, this publication was born with that concept in mind. The Islamic Bulletin started back in 1991, PRAYER LOCATIONS .................................... 15 and our mission remains the same--to deliver positive and uplifting Islamic material. -

Holy Qur'an Memorization, Prayers with Translation, Hadith with Translation, Attributes of Allah/ Salat, Religious Knowledge, Poems/ Qaseeda

Rabi Al Awwal 1438 November 2016 Issue 4 Special Features Holy Qur’an The Glorious Qur’an Message from Sadr Lajna And hold fast, all together, by National Correspondence the rope of Allah and be not National Events divided; and remember the Huzoor’s Sermon favor of Allah which He Taleem Matters bestowed upon you when you Tarbiyat Matters were enemies and He united Tabligh Matters your hearts in love, so that by His grace you became as Khidmat-e-Khalq Matters brothers; as you were o the Nasirat Matters brink of a pit of fire and He Nau Mubaiyat Matters saved you from it. Thus does Lajna 15-25 Matters Allah explain to you His Waqifat Matters commandments that you may be Urdu Section guided (3:104). All members are asked And worship Allah and to make use of the associate naught with Him, and resources provided by show kindness to parents, and to Jama’at and Lajna in kindred, and orphans, and the order to improve their needy, and to the neighbor that reading and their is a kinsman and the neighbor comprehension of the that is a stranger, and the Holy Qur’an. All companion by your side, and the Majalis are requested wayfarer, and those whom your to spend 10-15 minutes right hand possess. Surely, during their General Allah loves not the proud and Meetings to improve the boastful (4:37). their Tarteel. Lajna Matters November 2016 Ahadith None among you is a true believer unless he likes for his brother (in faith) what he likes for himself (Bukhari, Kitab ul Eeman). -

Speakers' Biographies

ISLAMIC SOCIETY OF NORTH AMERICA 53RD ANNUAL CONVENTION TURNING POINTS: NAVIGATING CHALLENGES, SEIZING OPPORTUNITIES Speakers’ Biographies SEPTEMBER 2 – 5, 2016 DONALD E. STEPHENS CONVENTION CENTER 9291 BRYN MAWR AVE • ROSEMONT, ILLINOIS www.isna.net Speaker Bio Book ISNA 53rd Annual Convention 2016 Rafik Beekun .................................................... 11 Table of Contents Ghalib Begg ...................................................... 11 Farha Abbasi ....................................................... 4 Khalid Beydoun ................................................ 12 Umar F. Abd-Allah .............................................. 4 Zahra Billoo ...................................................... 12 Nazeeh Abdul-Hakeem ....................................... 4 Kamran Bokhari ................................................ 12 Jamiah Adams ..................................................... 4 Maher Budeir ................................................... 12 Atiya Aftab .......................................................... 5 Rukhsana Chaudhry ......................................... 13 Kiran Ahmad ....................................................... 5 Rabia Chaudry .................................................. 13 Ambreen Ahmed ................................................ 5 Owaiz Dadabhoy .............................................. 13 Muzammil Ahmed .............................................. 5 Makram El-Amin .............................................. 13 Sameera Ahmed ................................................ -

2008 Ramadan Issue

The Prophet (SAW) said, “Salat (Prayer) is the first act that a person will be accountable for.” SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA GOLETA (Santa Barbara Area) MONROVIA Directions Start From Highway 5 MUSLIM COMM. CENTER OF GREATOR SAN DIEGO THE ISLAMIC SOCIETY OF SANTA BARBARA MASJID QURTUBA 12788 Rancho Penasquitos Blvd. San Diego, 92129, 158 Aero Camino Ave, Ste D, Goleta, 93117, 805- 1121 Huntington Dr, Monrovia, 91016, 626-305- 858-484-0074, 5S*CA-56 Ex 33*L Carmel Vly Rd*Ex SOUTH SOUTH SOUTH SOUTH SOUTH 968 9940, 101S*Los Carneros Rd Ex R*Hollister 0077, 5S*210W*Buena Vista Ex*Central L* Buena 8 Rancho Penasquitos Blvd R* www.gsdmcc.org 5 5 5 5 5 L*Aero Camino L* www.islamsb.org Vista R*Huntington L MASJID AL-TAQWA GRANADA HILLS MORENO VALLEY 2575 Imperial Ave, San Diego, 92102, 619-239-6738, ALTADENA ISLAMIC CENTER NORTHRIDGE ISLAMIC DEVELOPMENT CENTER MASJID TAQWA 5S*805S*Imperial Ave Ex 11439 Encino Ave, Granada Hills, 91344, 818-360- 24436 Webster St.,Moreno Valley, CA 92557, 951- MASJID HAMZA 2181 N. Lake Ave, Altadena, 91001, 626-398 3500, 5S*Ex 161B San Fernardo Rd R* R Balboa 247-8581, 5S*210E*I10E*I15S*60E*Ex Heacock*L 8392, 5S* 210E Pasadena*Ex N Arroyo Bl R*L W 9520 Padgett St #106, 92126, 619-571-2988, 5S*I- Blvd *R Rinaldi *L Encino Ave Sunnymead*R Indian* R Webster 805S*La Jolla Dr Ex* Miramar rd R*L Padgett Washington*L Lake Ave* [email protected] HAWTHORNE NEWHALL (Santa Clarita Area) ANAHEIM MASJID-AL-ANSAR THE ISLAMIC CENTER OF HAWTHORNE MUSLIM COMMUNITY CENTER 4014 Winona Ave., San Diego, 92105, 619-282-4407, MASJID AL-ANSAR 12209 S Hawthorne Way, Hawthorne,90250,310- 22607 6th St., 91321, 661-259-9008, 5S*Ex 1717 S. -

Domestic Intelligence: Our Rights and Our Safety Captures the Voices of Leading Government Officials

Since September 11, 2001, advancements in technology and shifts in counterterrorism DOMESTIC INTELLIGENCE: strategies have transformed America’s national security infrastructure. These shifts have eroded the boundaries between law enforcement and intelligence gathering and resulted in surveillance and intelligence collection programs that are more invasive than ever. Domestic Intelligence: Our Rights and Our Safety captures the voices of leading government officials, academics, and advocates on the burgeoning role RIGHTSOUR AND SAFETY of law enforcement in the collection of domestic intelligence. Brought together by a Brennan Center for Justice symposium, this diverse range of perspectives challenges us to reevaluate how we DOMESTIC can secure the safety of the nation while remaining faithful to the liberties we seek to protect. INTELLIGENCE: BRENNAN CENTER FOR JUSTICE OUR RIGHTS AND SAFETY Faiza Patel, editor Faiza Patel, editor at New York University School of Law 161 Avenue of the Americas 12th Floor New York, NY 10013 (646) 292-8310 www.brennancenter.org Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law DOMESTIC INTELLIGENCE: OUR RIGHTS AND OUR SAFETY Faiza Patel, editor About the Brennan Center The Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law is a non- partisan public policy and law institute that focuses on the fundamental issues of democracy and justice. Our work ranges from voting rights to campaign finance reform, from racial justice in criminal law to constitutional protection in the fight against terrorism. A singular institution — part think tank, part public interest law firm, part advocacy group — the Brennan Center combines scholarship, legislative and legal advocacy, and communications to win meaningful, measurable change in the public sector.