The Cells That Changed the World (Adapted from the 2003 Windows to the Sea Expedition)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anoxygenic Photosynthesis in Photolithotrophic Sulfur Bacteria and Their Role in Detoxication of Hydrogen Sulfide

antioxidants Review Anoxygenic Photosynthesis in Photolithotrophic Sulfur Bacteria and Their Role in Detoxication of Hydrogen Sulfide Ivan Kushkevych 1,* , Veronika Bosáková 1,2 , Monika Vítˇezová 1 and Simon K.-M. R. Rittmann 3,* 1 Department of Experimental Biology, Faculty of Science, Masaryk University, 62500 Brno, Czech Republic; [email protected] (V.B.); [email protected] (M.V.) 2 Department of Biology, Faculty of Medicine, Masaryk University, 62500 Brno, Czech Republic 3 Archaea Physiology & Biotechnology Group, Department of Functional and Evolutionary Ecology, Universität Wien, 1090 Vienna, Austria * Correspondence: [email protected] (I.K.); [email protected] (S.K.-M.R.R.); Tel.: +420-549-495-315 (I.K.); +431-427-776-513 (S.K.-M.R.R.) Abstract: Hydrogen sulfide is a toxic compound that can affect various groups of water microorgan- isms. Photolithotrophic sulfur bacteria including Chromatiaceae and Chlorobiaceae are able to convert inorganic substrate (hydrogen sulfide and carbon dioxide) into organic matter deriving energy from photosynthesis. This process takes place in the absence of molecular oxygen and is referred to as anoxygenic photosynthesis, in which exogenous electron donors are needed. These donors may be reduced sulfur compounds such as hydrogen sulfide. This paper deals with the description of this metabolic process, representatives of the above-mentioned families, and discusses the possibility using anoxygenic phototrophic microorganisms for the detoxification of toxic hydrogen sulfide. Moreover, their general characteristics, morphology, metabolism, and taxonomy are described as Citation: Kushkevych, I.; Bosáková, well as the conditions for isolation and cultivation of these microorganisms will be presented. V.; Vítˇezová,M.; Rittmann, S.K.-M.R. -

Limits of Life on Earth Some Archaea and Bacteria

Limits of life on Earth Thermophiles Temperatures up to ~55C are common, but T > 55C is Some archaea and bacteria (extremophiles) can live in associated usually with geothermal features (hot springs, environments that we would consider inhospitable to volcanic activity etc) life (heat, cold, acidity, high pressure etc) Thermophiles are organisms that can successfully live Distinguish between growth and survival: many organisms can survive intervals of harsh conditions but could not at high temperatures live permanently in such conditions (e.g. seeds, spores) Best studied extremophiles: may be relevant to the Interest: origin of life. Very hot environments tolerable for life do not seem to exist elsewhere in the Solar System • analogs for extraterrestrial environments • `extreme’ conditions may have been more common on the early Earth - origin of life? • some unusual environments (e.g. subterranean) are very widespread Extraterrestrial Life: Spring 2008 Extraterrestrial Life: Spring 2008 Grand Prismatic Spring, Yellowstone National Park Hydrothermal vents: high pressure in the deep ocean allows liquid water Colors on the edge of the at T >> 100C spring are caused by different colonies of thermophilic Vents emit superheated water (300C or cyanobacteria and algae more) that is rich in minerals Hottest water is lifeless, but `cooler’ ~50 species of such thermophiles - mostly archae with some margins support array of thermophiles: cyanobacteria and anaerobic photosynthetic bacteria oxidize sulphur, manganese, grow on methane + carbon monoxide etc… Sulfolobus: optimum T ~ 80C, minimum 60C, maximum 90C, also prefer a moderately acidic pH. Live by oxidizing sulfur Known examples can grow (i.e. multiply) at temperatures which is abundant near hot springs. -

PROTISTS Shore and the Waves Are Large, Often the Largest of a Storm Event, and with a Long Period

(seas), and these waves can mobilize boulders. During this phase of the storm the rapid changes in current direction caused by these large, short-period waves generate high accelerative forces, and it is these forces that ultimately can move even large boulders. Traditionally, most rocky-intertidal ecological stud- ies have been conducted on rocky platforms where the substrate is composed of stable basement rock. Projec- tiles tend to be uncommon in these types of habitats, and damage from projectiles is usually light. Perhaps for this reason the role of projectiles in intertidal ecology has received little attention. Boulder-fi eld intertidal zones are as common as, if not more common than, rock plat- forms. In boulder fi elds, projectiles are abundant, and the evidence of damage due to projectiles is obvious. Here projectiles may be one of the most important defi ning physical forces in the habitat. SEE ALSO THE FOLLOWING ARTICLES Geology, Coastal / Habitat Alteration / Hydrodynamic Forces / Wave Exposure FURTHER READING Carstens. T. 1968. Wave forces on boundaries and submerged bodies. Sarsia FIGURE 6 The intertidal zone on the north side of Cape Blanco, 34: 37–60. Oregon. The large, smooth boulders are made of serpentine, while Dayton, P. K. 1971. Competition, disturbance, and community organi- the surrounding rock from which the intertidal platform is formed zation: the provision and subsequent utilization of space in a rocky is sandstone. The smooth boulders are from a source outside the intertidal community. Ecological Monographs 45: 137–159. intertidal zone and were carried into the intertidal zone by waves. Levin, S. A., and R. -

Algae and Cyanobacteria in Coastal and Estuarine Waters

CHAPTER 7 Algae and cyanobacteria in coastal and estuarine waters n coastal and estuarine waters, algae range from single-celled forms to the seaweeds. ICyanobacteria are organisms with some characteristics of bacteria and some of algae. They are similar in size to the unicellular algae and, unlike other bacteria, contain blue-green or green pigments and are able to perform photosynthesis; thus, they are also termed blue-green algae. Algal blooms in the sea have occurred throughout recorded history but have been increasing during recent decades (Anderson, 1989; Smayda, 1989a; Hallegraeff, 1993). In several areas (e.g., the Baltic and North seas, the Adriatic Sea, Japanese coastal waters and the Gulf of Mexico), algal blooms are a recurring phe- nomenon. The increased frequency of occurrence has accompanied nutrient enrich- ment of coastal waters on a global scale (Smayda, 1989b). Blooms of non-toxic phytoplankton species and mass occurrences of macro-algae can affect the amenity value of recreational waters due to reduced transparency, dis- coloured water and scum formation. Furthermore, bloom degradation can be accom- panied by unpleasant odours, resulting in aesthetic problems (see chapter 9). Several human diseases have been reported to be associated with many toxic species of dinoflagellates, diatoms, nanoflagellates and cyanobacteria that occur in the marine environment (CDC, 1997). The effects of these algae on humans are due to some of their constituents, principally algal toxins. Marine algal toxins become a problem primarily because they may concentrate in shellfish and fish that are subsequently eaten by humans (CDR, 1991; Lehane, 2000), causing syndromes known as para- lytic shellfish poisoning (PSP), diarrhetic shellfish poisoning (DSP), amnesic shellfish poisoning (ASP), neurotoxic shellfish poisoning (NSP) and ciguatera fish poisoning (CFP). -

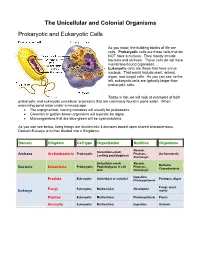

The Unicellular and Colonial Organisms Prokaryotic And

The Unicellular and Colonial Organisms Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Cells As you know, the building blocks of life are cells. Prokaryotic cells are those cells that do NOT have a nucleus. They mostly include bacteria and archaea. These cells do not have membrane-bound organelles. Eukaryotic cells are those that have a true nucleus. That would include plant, animal, algae, and fungal cells. As you can see, to the left, eukaryotic cells are typically larger than prokaryotic cells. Today in lab, we will look at examples of both prokaryotic and eukaryotic unicellular organisms that are commonly found in pond water. When examining pond water under a microscope… The unpigmented, moving microbes will usually be protozoans. Greenish or golden-brown organisms will typically be algae. Microorganisms that are blue-green will be cyanobacteria. As you can see below, living things are divided into 3 domains based upon shared characteristics. Domain Eukarya is further divided into 4 Kingdoms. Domain Kingdom Cell type Organization Nutrition Organisms Absorb, Unicellular-small; Prokaryotic Photsyn., Archaeacteria Archaea Archaebacteria Lacking peptidoglycan Chemosyn. Unicellular-small; Absorb, Bacteria, Prokaryotic Peptidoglycan in cell Photsyn., Bacteria Eubacteria Cyanobacteria wall Chemosyn. Ingestion, Eukaryotic Unicellular or colonial Protozoa, Algae Protista Photosynthesis Fungi, yeast, Fungi Eukaryotic Multicellular Absorption Eukarya molds Plantae Eukaryotic Multicellular Photosynthesis Plants Animalia Eukaryotic Multicellular Ingestion Animals Prokaryotic Organisms – the archaea, non-photosynthetic bacteria, and cyanobacteria Archaea - Microorganisms that resemble bacteria, but are different from them in certain aspects. Archaea cell walls do not include the macromolecule peptidoglycan, which is always found in the cell walls of bacteria. Archaea usually live in extreme, often very hot or salty environments, such as hot mineral springs or deep-sea hydrothermal vents. -

About Cyanobacteria BACKGROUND Cyanobacteria Are Single-Celled Organisms That Live in Fresh, Brackish, and Marine Water

About Cyanobacteria BACKGROUND Cyanobacteria are single-celled organisms that live in fresh, brackish, and marine water. They use sunlight to make their own food. In warm, nutrient-rich environments, microscopic cyanobacteria can grow quickly, creating blooms that spread across the water’s surface and may become visible. Because of the color, texture, and location of these blooms, the common name for cyanobacteria is blue-green algae. However, cyanobacteria are related more closely to bacteria than to algae. Cyanobacteria are found worldwide, from Brazil to China, Australia to the United States. In warmer climates, these organisms can grow year-round. Scientists have called cyanobacteria the origin of plants, and have credited cyanobacteria with providing nitrogen fertilizer for rice and beans. But blooms of cyanobacteria are not always helpful. When these blooms become harmful to the environment, animals, and humans, scientists call them cyanobacterial harmful algal blooms (CyanoHABs). Freshwater CyanoHABs can use up the oxygen and block the sunlight that other organisms need to live. They also can produce powerful toxins that affect the brain and liver of animals and humans. Because of concerns about CyanoHABs, which can grow in drinking water and recreational water, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has added cyanobacteria to its Drinking Water Contaminant Candidate List. This list identifies organisms and toxins that EPA considers to be priorities for investigation. ASSESSING THE IMPACT ON PUBLIC HEALTH Reports of poisonings associated with CyanoHABs date back to the late 1800s. Anecdotal evidence and data from laboratory animal research suggest that cyanobacterial toxins can cause a range of adverse human health effects, yet few studies have explored the links between CyanoHABs and human health. -

Rhythmicity of Coastal Marine Picoeukaryotes, Bacteria and Archaea Despite Irregular Environmental Perturbations

Rhythmicity of coastal marine picoeukaryotes, bacteria and archaea despite irregular environmental perturbations Stefan Lambert, Margot Tragin, Jean-Claude Lozano, Jean-François Ghiglione, Daniel Vaulot, François-Yves Bouget, Pierre Galand To cite this version: Stefan Lambert, Margot Tragin, Jean-Claude Lozano, Jean-François Ghiglione, Daniel Vaulot, et al.. Rhythmicity of coastal marine picoeukaryotes, bacteria and archaea despite irregular environmental perturbations. ISME Journal, Nature Publishing Group, 2019, 13 (2), pp.388-401. 10.1038/s41396- 018-0281-z. hal-02326251 HAL Id: hal-02326251 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02326251 Submitted on 19 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Rhythmicity of coastal marine picoeukaryotes, bacteria and archaea despite irregular environmental perturbations Stefan Lambert, Margot Tragin, Jean-Claude Lozano, Jean-François Ghiglione, Daniel Vaulot, François-Yves Bouget, Pierre Galand To cite this version: Stefan Lambert, Margot Tragin, Jean-Claude Lozano, Jean-François Ghiglione, Daniel -

CYANOBACTERIA (BLUE-GREEN ALGAE) BLOOMS When in Doubt, It’S Best to Keep Out!

Cyanobacteria Blooms FAQs CYANOBACTERIA (BLUE-GREEN ALGAE) BLOOMS When in doubt, it’s best to keep out! What are cyanobacteria? Cyanobacteria, also called blue-green algae, are microscopic organisms found naturally in all types of water. These single-celled organisms live in fresh, brackish (combined salt and fresh water), and marine water. These organisms use sunlight to make their own food. In warm, nutrient-rich (high in phosphorus and nitrogen) environments, cyanobacteria can multiply quickly, creating blooms that spread across the water’s surface. The blooms might become visible. How are cyanobacteria blooms formed? Cyanobacteria blooms form when cyanobacteria, which are normally found in the water, start to multiply very quickly. Blooms can form in warm, slow-moving waters that are rich in nutrients from sources such as fertilizer runoff or septic tank overflows. Cyanobacteria blooms need nutrients to survive. The blooms can form at any time, but most often form in late summer or early fall. What does a cyanobacteria bloom look like? You might or might not be able to see cyanobacteria blooms. They sometimes stay below the water’s surface, they sometimes float to the surface. Some cyanobacteria blooms can look like foam, scum, or mats, particularly when the wind blows them toward a shoreline. The blooms can be blue, bright green, brown, or red. Blooms sometimes look like paint floating on the water’s surface. As cyanobacteria in a bloom die, the water may smell bad, similar to rotting plants. Why are some cyanbacteria blooms harmful? Cyanobacteria blooms that harm people, animals, or the environment are called cyanobacteria harmful algal blooms. -

Factors Controlling the Community Structure of Picoplankton in Contrasting Marine Environments

Biogeosciences, 15, 6199–6220, 2018 https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-15-6199-2018 © Author(s) 2018. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Factors controlling the community structure of picoplankton in contrasting marine environments Jose Luis Otero-Ferrer1, Pedro Cermeño2, Antonio Bode6, Bieito Fernández-Castro1,3, Josep M. Gasol2,5, Xosé Anxelu G. Morán4, Emilio Marañon1, Victor Moreira-Coello1, Marta M. Varela6, Marina Villamaña1, and Beatriz Mouriño-Carballido1 1Departamento de Ecoloxía e Bioloxía Animal, Universidade de Vigo, Vigo, Spain 2Institut de Ciències del Mar, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Barcelona, Spain 3Departamento de Oceanografía, Instituto de investigacións Mariñas (IIM-CSIC), Vigo, Spain 4King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST), Read Sea Research Center, Biological and Environmental Sciences and Engineering Division, Thuwal, Saudi Arabia 5Centre for Marine Ecosystem Research, School of Sciences, Edith Cowan University, WA, Perth, Australia 6Centro Oceanográfico de A Coruña, Instituto Español de Oceanografía (IEO), A Coruña, Spain Correspondence: Jose Luis Otero-Ferrer ([email protected]) Received: 27 April 2018 – Discussion started: 4 June 2018 Revised: 4 October 2018 – Accepted: 10 October 2018 – Published: 26 October 2018 Abstract. The effect of inorganic nutrients on planktonic as- played a significant role. Nitrate supply was the only fac- semblages has traditionally relied on concentrations rather tor that allowed the distinction among the ecological -

Dry Weight and Cell Density of Individual Algal and Cyanobacterial Cells for Algae

Dry Weight and Cell Density of Individual Algal and Cyanobacterial Cells for Algae Research and Development _______________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science _____________________________________________________ by WENNA HU Dr. Zhiqiang Hu, Thesis Supervisor July 2014 The undersigned, appointed by the Dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled Dry Weight and Cell Density of Individual Algal and Cyanobacterial Cells for Algae Research and Development presented by Wenna Hu, a candidate for the degree of Master of Science, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor Zhiqiang Hu Professor Enos C. Inniss Professor Pamela Brown DEDICATION I dedicate this thesis to my beloved parents, whose moral encouragement and support help me earn my Master’s degree. Acknowledgements Foremost, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my advisor and mentor Dr. Zhiqiang Hu for the continuous support of my graduate studies, for his patience, motivation, enthusiasm, and immense knowledge. His guidance helped me in all the time of research and writing of this thesis. Without his guidance and persistent help this thesis would not have been possible. I would like to thank my committee members, Dr. Enos Inniss and Dr. Pamela Brown for being my graduation thesis committee. Their guidance and enthusiasm of my graduate research is greatly appreciated. Thanks to Daniel Jackson in immunology core for the flow cytometer operation training, and Arpine Mikayelyan in life science center for fluorescent images acquisition. -

Ecological Observations on Phototrophic Sulfur Bacteria and the Role of These Bacteria Inth Esulfu R Cycle of Monomictic Lake Vechten (The Netherlands)

Ecological observations on phototrophic sulfur bacteria and the role of these bacteria inth esulfu r cycle of monomictic Lake Vechten (The Netherlands). C.L.M. Steenbergen, H.J. Korthals and M.va n Nes LimnologicalInstitute, Vijverhof laboratory.Rijksstraatweg 6, 3631 ACNieuwersluis, The Netherlands Abstract. Lake Vechten, located centrally in TheNetherlands , was formed in 1941 bysan d digging. Its total area is4. 7 ha, themaximu m depth is 11 m and the mean depth is6 m .Th e water balancei s regulated by rainfall, evaporation and horizontal groundwater flow; the residence time is approximate ly 2 years. Lake Vechten can be classified as warm-monomictic in most years; the stable summer stratification starts in Mayan d lasts till the endo f October. Thelak e ismeso-eutrophic ; duringit s history the sulfate concentration hasincrease d considerably. Sulfide isproduce d mainly in thesedi ment, its concentration inth e bottom water isrestricte d byth e occurrence ofhig h amounts of ferrous iron. At present small quantities offre e sulfide canb efoun d and phototrophic sulfur bacteria develop at theoxygen-sulfid e borderline. Phototrophic sulfur bacteria occurred in a two layer pattern; the upper one at 6.5-7.0 mdept h contained Chloronema-typefilaments , the deeper one at 7.0-7.5 mdept h consisted mainly ofChroma- tium anda brown-colore d Chlorobium. During their maximal development in September the photo trophic sulfur bacteria contributed on an areal basis ca. 18% t oth etota l pelagic primary production of thelake . Using sediment traps it wasshow n that phototrophic sulfur bacteria sank throughoutth e season at a rate of ca. -

Chapter 7 Freshwater Algae and Cyanobacteria

Guidelines for Safe Recreational-water Environments Draft for Consultation Vol 1: Coastal and Fresh-waters October 1998 CHAPTER 7 FRESHWATER ALGAE AND CYANOBACTERIA 125 Guidelines for Safe Recreational-water Environments Draft for Consultation Vol 1: Coastal and Fresh-waters October 1998 In freshwaters, the term "algae" refers to microscopically small, in principle unicellular organisms, some of which form colonies and thus reach sizes visible to the naked eye as minute green particles. These organisms are usually finely dispersed throughout the water and may cause considerable turbidity if they attain high densities. "Cyanobacteria" are organisms with some characteristics of bacteria and some of algae. They are similar to algae in size, and unlike other bacteria, they contain blue-green or green pigments and thus perform photosynthesis. Therefore, they are also termed "blue-green algae". In contrast to most algae, many species of cyanobacteria may accumulate to surface scums, often termed "blooms", of extremely high cell density. Livestock poisonings have lead to the study of cyanobacterial toxicity, and during the past 2-3 decades, the chemical structures of a number of cyanobacterial toxins (‘cyanotoxins’) have been identified and their mechanisms of toxicity established. In contrast, toxic metabolites from freshwater algae have scarcely been investigated, but toxicity has been shown for freshwater species of Dinophyceae and Prymnesiophyceae (see below). As marine species of these genera often contain toxins, it is reasonable to expect toxic species among these groups in freshwaters as well. In comparing the relative cause for concern arising from toxic cyanobacteria to that arising from potentially toxic freshwater algae, mechanisms of cell concentrations are a key factor.