Chapter 7 Freshwater Algae and Cyanobacteria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anoxygenic Photosynthesis in Photolithotrophic Sulfur Bacteria and Their Role in Detoxication of Hydrogen Sulfide

antioxidants Review Anoxygenic Photosynthesis in Photolithotrophic Sulfur Bacteria and Their Role in Detoxication of Hydrogen Sulfide Ivan Kushkevych 1,* , Veronika Bosáková 1,2 , Monika Vítˇezová 1 and Simon K.-M. R. Rittmann 3,* 1 Department of Experimental Biology, Faculty of Science, Masaryk University, 62500 Brno, Czech Republic; [email protected] (V.B.); [email protected] (M.V.) 2 Department of Biology, Faculty of Medicine, Masaryk University, 62500 Brno, Czech Republic 3 Archaea Physiology & Biotechnology Group, Department of Functional and Evolutionary Ecology, Universität Wien, 1090 Vienna, Austria * Correspondence: [email protected] (I.K.); [email protected] (S.K.-M.R.R.); Tel.: +420-549-495-315 (I.K.); +431-427-776-513 (S.K.-M.R.R.) Abstract: Hydrogen sulfide is a toxic compound that can affect various groups of water microorgan- isms. Photolithotrophic sulfur bacteria including Chromatiaceae and Chlorobiaceae are able to convert inorganic substrate (hydrogen sulfide and carbon dioxide) into organic matter deriving energy from photosynthesis. This process takes place in the absence of molecular oxygen and is referred to as anoxygenic photosynthesis, in which exogenous electron donors are needed. These donors may be reduced sulfur compounds such as hydrogen sulfide. This paper deals with the description of this metabolic process, representatives of the above-mentioned families, and discusses the possibility using anoxygenic phototrophic microorganisms for the detoxification of toxic hydrogen sulfide. Moreover, their general characteristics, morphology, metabolism, and taxonomy are described as Citation: Kushkevych, I.; Bosáková, well as the conditions for isolation and cultivation of these microorganisms will be presented. V.; Vítˇezová,M.; Rittmann, S.K.-M.R. -

Cobia Database Articles Final Revision 2.0, 2-1-2017

Revision 2.0 (2/1/2017) University of Miami Article TITLE DESCRIPTION AUTHORS SOURCE YEAR TOPICS Number Habitat 1 Gasterosteus canadus Linné [Latin] [No Abstract Available - First known description of cobia morphology in Carolina habitat by D. Garden.] Linnaeus, C. Systema Naturæ, ed. 12, vol. 1, 491 1766 Wild (Atlantic/Pacific) Ichthyologie, vol. 10, Iconibus ex 2 Scomber niger Bloch [No Abstract Available - Description and alternative nomenclature of cobia.] Bloch, M. E. 1793 Wild (Atlantic/Pacific) illustratum. Berlin. p . 48 The Fisheries and Fishery Industries of the Under this head was to be carried on the study of the useful aquatic animals and plants of the country, as well as of seals, whales, tmtles, fishes, lobsters, crabs, oysters, clams, etc., sponges, and marine plants aml inorganic products of U.S. Commission on Fisheries, Washington, 3 United States. Section 1: Natural history of Goode, G.B. 1884 Wild (Atlantic/Pacific) the sea with reference to (A) geographical distribution, (B) size, (C) abundance, (D) migrations and movements, (E) food and rate of growth, (F) mode of reproduction, (G) economic value and uses. D.C., 895 p. useful aquatic animals Notes on the occurrence of a young crab- Proceedings of the U.S. National Museum 4 eater (Elecate canada), from the lower [No Abstract Available - A description of cobia in the lower Hudson Eiver.] Fisher, A.K. 1891 Wild (Atlantic/Pacific) 13, 195 Hudson Valley, New York The nomenclature of Rachicentron or Proceedings of the U.S. National Museum Habitat 5 Elacate, a genus of acanthopterygian The universally accepted name Elucate must unfortunately be supplanted by one entirely unknown to fame, overlooked by all naturalists, and found in no nomenclator. -

Limits of Life on Earth Some Archaea and Bacteria

Limits of life on Earth Thermophiles Temperatures up to ~55C are common, but T > 55C is Some archaea and bacteria (extremophiles) can live in associated usually with geothermal features (hot springs, environments that we would consider inhospitable to volcanic activity etc) life (heat, cold, acidity, high pressure etc) Thermophiles are organisms that can successfully live Distinguish between growth and survival: many organisms can survive intervals of harsh conditions but could not at high temperatures live permanently in such conditions (e.g. seeds, spores) Best studied extremophiles: may be relevant to the Interest: origin of life. Very hot environments tolerable for life do not seem to exist elsewhere in the Solar System • analogs for extraterrestrial environments • `extreme’ conditions may have been more common on the early Earth - origin of life? • some unusual environments (e.g. subterranean) are very widespread Extraterrestrial Life: Spring 2008 Extraterrestrial Life: Spring 2008 Grand Prismatic Spring, Yellowstone National Park Hydrothermal vents: high pressure in the deep ocean allows liquid water Colors on the edge of the at T >> 100C spring are caused by different colonies of thermophilic Vents emit superheated water (300C or cyanobacteria and algae more) that is rich in minerals Hottest water is lifeless, but `cooler’ ~50 species of such thermophiles - mostly archae with some margins support array of thermophiles: cyanobacteria and anaerobic photosynthetic bacteria oxidize sulphur, manganese, grow on methane + carbon monoxide etc… Sulfolobus: optimum T ~ 80C, minimum 60C, maximum 90C, also prefer a moderately acidic pH. Live by oxidizing sulfur Known examples can grow (i.e. multiply) at temperatures which is abundant near hot springs. -

PROTISTS Shore and the Waves Are Large, Often the Largest of a Storm Event, and with a Long Period

(seas), and these waves can mobilize boulders. During this phase of the storm the rapid changes in current direction caused by these large, short-period waves generate high accelerative forces, and it is these forces that ultimately can move even large boulders. Traditionally, most rocky-intertidal ecological stud- ies have been conducted on rocky platforms where the substrate is composed of stable basement rock. Projec- tiles tend to be uncommon in these types of habitats, and damage from projectiles is usually light. Perhaps for this reason the role of projectiles in intertidal ecology has received little attention. Boulder-fi eld intertidal zones are as common as, if not more common than, rock plat- forms. In boulder fi elds, projectiles are abundant, and the evidence of damage due to projectiles is obvious. Here projectiles may be one of the most important defi ning physical forces in the habitat. SEE ALSO THE FOLLOWING ARTICLES Geology, Coastal / Habitat Alteration / Hydrodynamic Forces / Wave Exposure FURTHER READING Carstens. T. 1968. Wave forces on boundaries and submerged bodies. Sarsia FIGURE 6 The intertidal zone on the north side of Cape Blanco, 34: 37–60. Oregon. The large, smooth boulders are made of serpentine, while Dayton, P. K. 1971. Competition, disturbance, and community organi- the surrounding rock from which the intertidal platform is formed zation: the provision and subsequent utilization of space in a rocky is sandstone. The smooth boulders are from a source outside the intertidal community. Ecological Monographs 45: 137–159. intertidal zone and were carried into the intertidal zone by waves. Levin, S. A., and R. -

Algae and Cyanobacteria in Coastal and Estuarine Waters

CHAPTER 7 Algae and cyanobacteria in coastal and estuarine waters n coastal and estuarine waters, algae range from single-celled forms to the seaweeds. ICyanobacteria are organisms with some characteristics of bacteria and some of algae. They are similar in size to the unicellular algae and, unlike other bacteria, contain blue-green or green pigments and are able to perform photosynthesis; thus, they are also termed blue-green algae. Algal blooms in the sea have occurred throughout recorded history but have been increasing during recent decades (Anderson, 1989; Smayda, 1989a; Hallegraeff, 1993). In several areas (e.g., the Baltic and North seas, the Adriatic Sea, Japanese coastal waters and the Gulf of Mexico), algal blooms are a recurring phe- nomenon. The increased frequency of occurrence has accompanied nutrient enrich- ment of coastal waters on a global scale (Smayda, 1989b). Blooms of non-toxic phytoplankton species and mass occurrences of macro-algae can affect the amenity value of recreational waters due to reduced transparency, dis- coloured water and scum formation. Furthermore, bloom degradation can be accom- panied by unpleasant odours, resulting in aesthetic problems (see chapter 9). Several human diseases have been reported to be associated with many toxic species of dinoflagellates, diatoms, nanoflagellates and cyanobacteria that occur in the marine environment (CDC, 1997). The effects of these algae on humans are due to some of their constituents, principally algal toxins. Marine algal toxins become a problem primarily because they may concentrate in shellfish and fish that are subsequently eaten by humans (CDR, 1991; Lehane, 2000), causing syndromes known as para- lytic shellfish poisoning (PSP), diarrhetic shellfish poisoning (DSP), amnesic shellfish poisoning (ASP), neurotoxic shellfish poisoning (NSP) and ciguatera fish poisoning (CFP). -

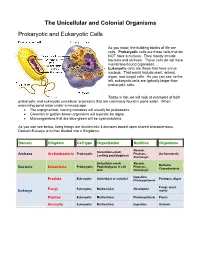

The Unicellular and Colonial Organisms Prokaryotic And

The Unicellular and Colonial Organisms Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Cells As you know, the building blocks of life are cells. Prokaryotic cells are those cells that do NOT have a nucleus. They mostly include bacteria and archaea. These cells do not have membrane-bound organelles. Eukaryotic cells are those that have a true nucleus. That would include plant, animal, algae, and fungal cells. As you can see, to the left, eukaryotic cells are typically larger than prokaryotic cells. Today in lab, we will look at examples of both prokaryotic and eukaryotic unicellular organisms that are commonly found in pond water. When examining pond water under a microscope… The unpigmented, moving microbes will usually be protozoans. Greenish or golden-brown organisms will typically be algae. Microorganisms that are blue-green will be cyanobacteria. As you can see below, living things are divided into 3 domains based upon shared characteristics. Domain Eukarya is further divided into 4 Kingdoms. Domain Kingdom Cell type Organization Nutrition Organisms Absorb, Unicellular-small; Prokaryotic Photsyn., Archaeacteria Archaea Archaebacteria Lacking peptidoglycan Chemosyn. Unicellular-small; Absorb, Bacteria, Prokaryotic Peptidoglycan in cell Photsyn., Bacteria Eubacteria Cyanobacteria wall Chemosyn. Ingestion, Eukaryotic Unicellular or colonial Protozoa, Algae Protista Photosynthesis Fungi, yeast, Fungi Eukaryotic Multicellular Absorption Eukarya molds Plantae Eukaryotic Multicellular Photosynthesis Plants Animalia Eukaryotic Multicellular Ingestion Animals Prokaryotic Organisms – the archaea, non-photosynthetic bacteria, and cyanobacteria Archaea - Microorganisms that resemble bacteria, but are different from them in certain aspects. Archaea cell walls do not include the macromolecule peptidoglycan, which is always found in the cell walls of bacteria. Archaea usually live in extreme, often very hot or salty environments, such as hot mineral springs or deep-sea hydrothermal vents. -

About Cyanobacteria BACKGROUND Cyanobacteria Are Single-Celled Organisms That Live in Fresh, Brackish, and Marine Water

About Cyanobacteria BACKGROUND Cyanobacteria are single-celled organisms that live in fresh, brackish, and marine water. They use sunlight to make their own food. In warm, nutrient-rich environments, microscopic cyanobacteria can grow quickly, creating blooms that spread across the water’s surface and may become visible. Because of the color, texture, and location of these blooms, the common name for cyanobacteria is blue-green algae. However, cyanobacteria are related more closely to bacteria than to algae. Cyanobacteria are found worldwide, from Brazil to China, Australia to the United States. In warmer climates, these organisms can grow year-round. Scientists have called cyanobacteria the origin of plants, and have credited cyanobacteria with providing nitrogen fertilizer for rice and beans. But blooms of cyanobacteria are not always helpful. When these blooms become harmful to the environment, animals, and humans, scientists call them cyanobacterial harmful algal blooms (CyanoHABs). Freshwater CyanoHABs can use up the oxygen and block the sunlight that other organisms need to live. They also can produce powerful toxins that affect the brain and liver of animals and humans. Because of concerns about CyanoHABs, which can grow in drinking water and recreational water, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has added cyanobacteria to its Drinking Water Contaminant Candidate List. This list identifies organisms and toxins that EPA considers to be priorities for investigation. ASSESSING THE IMPACT ON PUBLIC HEALTH Reports of poisonings associated with CyanoHABs date back to the late 1800s. Anecdotal evidence and data from laboratory animal research suggest that cyanobacterial toxins can cause a range of adverse human health effects, yet few studies have explored the links between CyanoHABs and human health. -

A Guide to Harmful and Toxic Creatures in the Goa of Jordan

Published by the Royal Marine Conservation Society of Jordan. P. O. Box 831051, Abdel Aziz El Thaalbi St., Shmesani 11183. Amman Copyright: © The Royal Marine Conservation Society of Jordan Reproduction of this publication for educational and other non- commercial purposes is authorized without prior written approval from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. ISBN: 978-9957-8740-1-8 Deposit Number at the National Library: 2619/6/2016 Citation: Eid, E and Al Tawaha, M. (2016). A Guide to Harmful and Toxic Creature in the Gulf of Aqaba of Jordan. The Royal Marine Conservation Society of Jordan. ISBN: 978-9957-8740-1-8. Pp 84. Material was reviewed by Dr Nidal Al Oran, International Research Center for Water, Environment and Energy\ Al Balqa’ Applied University,and Dr. Omar Attum from Indiana University Southeast at the United State of America. Cover page: Vlad61; Shutterstock Library All photographs used in this publication remain the property of the original copyright holder, and it should not be reproduced or used in other contexts without permission. 1 Content Index of Creatures Described in this Guide ......................................................... 5 Preface ................................................................................................................ 6 Part One: Introduction ......................................................................................... 8 1.1 The Gulf of Aqaba; Jordan ......................................................................... 8 1.2 Aqaba; -

Rhythmicity of Coastal Marine Picoeukaryotes, Bacteria and Archaea Despite Irregular Environmental Perturbations

Rhythmicity of coastal marine picoeukaryotes, bacteria and archaea despite irregular environmental perturbations Stefan Lambert, Margot Tragin, Jean-Claude Lozano, Jean-François Ghiglione, Daniel Vaulot, François-Yves Bouget, Pierre Galand To cite this version: Stefan Lambert, Margot Tragin, Jean-Claude Lozano, Jean-François Ghiglione, Daniel Vaulot, et al.. Rhythmicity of coastal marine picoeukaryotes, bacteria and archaea despite irregular environmental perturbations. ISME Journal, Nature Publishing Group, 2019, 13 (2), pp.388-401. 10.1038/s41396- 018-0281-z. hal-02326251 HAL Id: hal-02326251 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02326251 Submitted on 19 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Rhythmicity of coastal marine picoeukaryotes, bacteria and archaea despite irregular environmental perturbations Stefan Lambert, Margot Tragin, Jean-Claude Lozano, Jean-François Ghiglione, Daniel Vaulot, François-Yves Bouget, Pierre Galand To cite this version: Stefan Lambert, Margot Tragin, Jean-Claude Lozano, Jean-François Ghiglione, Daniel -

Proceedings of the United States National Museum

NOTE ON THE GENERA OE SYNANCEINE AND PELORINE FISHES. By Theodore Gill, Honorarii Associate in Zoology. For a long time I have been in doubt respecting- the application of the name Synanceia and the consequent nomenclature of some other genera of the same group. Complication has resulted by reason of the intrusion of the incompetent Swainson into the field. In 1801 Bloch and Schneider's name Synanceja was published (p. 194) with a definition, and the only species mentioned were named as follows: 1. HoRRiDA Synanceia horrida. 2. Uranoscopa Tracldcephalus uranoscopus. 3. Verrucosa Synanceia verrucosa. 4. DiDACTYLA Simopias didactylus. 5. RuBicuNDA Simopias didactylus. 6. Papillosus Scorpsena cottoides. Two of the species having been withdrawn from the genus by Cuvier to foi'm the genus Pelor (1817), and one to serve for the genus Trachi- cephalus (1839), the name Synanceja was thus restricted to tlie horrida and verrucosa. In 1839 Swainson attempted to reclassif}^ the Sjmanceines and named three genera, but on each of the three pages of his work (II, pp. 61, 180, 268) in which he treats of those fishes he has expressed difl'erent views. On page 61 the names of Sj^nanchia, Pelor, Erosa, Trichophasia, and Hemitripterus appear as "genera of the Synanchinte" and analogues of five genera of "Scorpaeninte." On page 180 the following names are given under the head of Synanchinae: Agriopus. Synanchia, with three subgenera, viz: Synanchia. Bufichthys. TrachicephahxH. Trichodon. Proceedings U. S. National Museum, Vol. XXVIII— No. 1394. Proc. N. M. vol. xxviii—0-1 15 221 222 PROCEEDINGS OF THE NATIONAL MUSEUM. -

Venom Evolution Widespread in Fishes: a Phylogenetic Road Map for the Bioprospecting of Piscine Venoms

Journal of Heredity 2006:97(3):206–217 ª The American Genetic Association. 2006. All rights reserved. doi:10.1093/jhered/esj034 For permissions, please email: [email protected]. Advance Access publication June 1, 2006 Venom Evolution Widespread in Fishes: A Phylogenetic Road Map for the Bioprospecting of Piscine Venoms WILLIAM LEO SMITH AND WARD C. WHEELER From the Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Environmental Biology, Columbia University, 1200 Amsterdam Avenue, New York, NY 10027 (Leo Smith); Division of Vertebrate Zoology (Ichthyology), American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79th Street, New York, NY 10024-5192 (Leo Smith); and Division of Invertebrate Zoology, American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79th Street, New York, NY 10024-5192 (Wheeler). Address correspondence to W. L. Smith at the address above, or e-mail: [email protected]. Abstract Knowledge of evolutionary relationships or phylogeny allows for effective predictions about the unstudied characteristics of species. These include the presence and biological activity of an organism’s venoms. To date, most venom bioprospecting has focused on snakes, resulting in six stroke and cancer treatment drugs that are nearing U.S. Food and Drug Administration review. Fishes, however, with thousands of venoms, represent an untapped resource of natural products. The first step in- volved in the efficient bioprospecting of these compounds is a phylogeny of venomous fishes. Here, we show the results of such an analysis and provide the first explicit suborder-level phylogeny for spiny-rayed fishes. The results, based on ;1.1 million aligned base pairs, suggest that, in contrast to previous estimates of 200 venomous fishes, .1,200 fishes in 12 clades should be presumed venomous. -

CYANOBACTERIA (BLUE-GREEN ALGAE) BLOOMS When in Doubt, It’S Best to Keep Out!

Cyanobacteria Blooms FAQs CYANOBACTERIA (BLUE-GREEN ALGAE) BLOOMS When in doubt, it’s best to keep out! What are cyanobacteria? Cyanobacteria, also called blue-green algae, are microscopic organisms found naturally in all types of water. These single-celled organisms live in fresh, brackish (combined salt and fresh water), and marine water. These organisms use sunlight to make their own food. In warm, nutrient-rich (high in phosphorus and nitrogen) environments, cyanobacteria can multiply quickly, creating blooms that spread across the water’s surface. The blooms might become visible. How are cyanobacteria blooms formed? Cyanobacteria blooms form when cyanobacteria, which are normally found in the water, start to multiply very quickly. Blooms can form in warm, slow-moving waters that are rich in nutrients from sources such as fertilizer runoff or septic tank overflows. Cyanobacteria blooms need nutrients to survive. The blooms can form at any time, but most often form in late summer or early fall. What does a cyanobacteria bloom look like? You might or might not be able to see cyanobacteria blooms. They sometimes stay below the water’s surface, they sometimes float to the surface. Some cyanobacteria blooms can look like foam, scum, or mats, particularly when the wind blows them toward a shoreline. The blooms can be blue, bright green, brown, or red. Blooms sometimes look like paint floating on the water’s surface. As cyanobacteria in a bloom die, the water may smell bad, similar to rotting plants. Why are some cyanbacteria blooms harmful? Cyanobacteria blooms that harm people, animals, or the environment are called cyanobacteria harmful algal blooms.