Remembering Some Early Computers, 1948-19601

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Early Stored Program Computers

Stored Program Computers Thomas J. Bergin Computing History Museum American University 7/9/2012 1 Early Thoughts about Stored Programming • January 1944 Moore School team thinks of better ways to do things; leverages delay line memories from War research • September 1944 John von Neumann visits project – Goldstine’s meeting at Aberdeen Train Station • October 1944 Army extends the ENIAC contract research on EDVAC stored-program concept • Spring 1945 ENIAC working well • June 1945 First Draft of a Report on the EDVAC 7/9/2012 2 First Draft Report (June 1945) • John von Neumann prepares (?) a report on the EDVAC which identifies how the machine could be programmed (unfinished very rough draft) – academic: publish for the good of science – engineers: patents, patents, patents • von Neumann never repudiates the myth that he wrote it; most members of the ENIAC team contribute ideas; Goldstine note about “bashing” summer7/9/2012 letters together 3 • 1.0 Definitions – The considerations which follow deal with the structure of a very high speed automatic digital computing system, and in particular with its logical control…. – The instructions which govern this operation must be given to the device in absolutely exhaustive detail. They include all numerical information which is required to solve the problem…. – Once these instructions are given to the device, it must be be able to carry them out completely and without any need for further intelligent human intervention…. • 2.0 Main Subdivision of the System – First: since the device is a computor, it will have to perform the elementary operations of arithmetics…. – Second: the logical control of the device is the proper sequencing of its operations (by…a control organ. -

Computer Organization and Architecture Designing for Performance Ninth Edition

COMPUTER ORGANIZATION AND ARCHITECTURE DESIGNING FOR PERFORMANCE NINTH EDITION William Stallings Boston Columbus Indianapolis New York San Francisco Upper Saddle River Amsterdam Cape Town Dubai London Madrid Milan Munich Paris Montréal Toronto Delhi Mexico City São Paulo Sydney Hong Kong Seoul Singapore Taipei Tokyo Editorial Director: Marcia Horton Designer: Bruce Kenselaar Executive Editor: Tracy Dunkelberger Manager, Visual Research: Karen Sanatar Associate Editor: Carole Snyder Manager, Rights and Permissions: Mike Joyce Director of Marketing: Patrice Jones Text Permission Coordinator: Jen Roach Marketing Manager: Yez Alayan Cover Art: Charles Bowman/Robert Harding Marketing Coordinator: Kathryn Ferranti Lead Media Project Manager: Daniel Sandin Marketing Assistant: Emma Snider Full-Service Project Management: Shiny Rajesh/ Director of Production: Vince O’Brien Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Managing Editor: Jeff Holcomb Composition: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Production Project Manager: Kayla Smith-Tarbox Printer/Binder: Edward Brothers Production Editor: Pat Brown Cover Printer: Lehigh-Phoenix Color/Hagerstown Manufacturing Buyer: Pat Brown Text Font: Times Ten-Roman Creative Director: Jayne Conte Credits: Figure 2.14: reprinted with permission from The Computer Language Company, Inc. Figure 17.10: Buyya, Rajkumar, High-Performance Cluster Computing: Architectures and Systems, Vol I, 1st edition, ©1999. Reprinted and Electronically reproduced by permission of Pearson Education, Inc. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, Figure 17.11: Reprinted with permission from Ethernet Alliance. Credits and acknowledgments borrowed from other sources and reproduced, with permission, in this textbook appear on the appropriate page within text. Copyright © 2013, 2010, 2006 by Pearson Education, Inc., publishing as Prentice Hall. All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America. -

Computer Organization & Architecture Eie

COMPUTER ORGANIZATION & ARCHITECTURE EIE 411 Course Lecturer: Engr Banji Adedayo. Reg COREN. The characteristics of different computers vary considerably from category to category. Computers for data processing activities have different features than those with scientific features. Even computers configured within the same application area have variations in design. Computer architecture is the science of integrating those components to achieve a level of functionality and performance. It is logical organization or designs of the hardware that make up the computer system. The internal organization of a digital system is defined by the sequence of micro operations it performs on the data stored in its registers. The internal structure of a MICRO-PROCESSOR is called its architecture and includes the number lay out and functionality of registers, memory cell, decoders, controllers and clocks. HISTORY OF COMPUTER HARDWARE The first use of the word ‘Computer’ was recorded in 1613, referring to a person who carried out calculation or computation. A brief History: Computer as we all know 2day had its beginning with 19th century English Mathematics Professor named Chales Babage. He designed the analytical engine and it was this design that the basic frame work of the computer of today are based on. 1st Generation 1937-1946 The first electronic digital computer was built by Dr John V. Atanasoff & Berry Cliford (ABC). In 1943 an electronic computer named colossus was built for military. 1946 – The first general purpose digital computer- the Electronic Numerical Integrator and computer (ENIAC) was built. This computer weighed 30 tons and had 18,000 vacuum tubes which were used for processing. -

Id Question Microprocessor Is the Example of ___Architecture. A

Id Question Microprocessor is the example of _______ architecture. A Princeton B Von Neumann C Rockwell D Harvard Answer A Marks 1 Unit 1 Id Question _______ bus is unidirectional. A Data B Address C Control D None of these Answer B Marks 1 Unit 1 Id Question Use of _______isolates CPU form frequent accesses to main memory. A Local I/O controller B Expansion bus interface C Cache structure D System bus Answer C Marks 1 Unit 1 Id Question _______ buffers data transfer between system bus and I/O controllers on expansion bus. A Local I/O controller B Expansion bus interface C Cache structure D None of these Answer B Marks 1 Unit 1 Id Question ______ Timing involves a clock line. A Synchronous B Asynchronous C Asymmetric D None of these Answer A Marks 1 Unit 1 Id Question -----timing takes advantage of mixture of slow and fast devices, sharing the same bus A Synchronous B asynchronous C Asymmetric D None of these Answer B Marks 1 Unit 1 Id st Question In 1 generation _____language was used to prepare programs. A Machine B Assembly C High level programming D Pseudo code Answer B Marks 1 Unit 1 Id Question The transistor was invented at ________ laboratories. A AT &T B AT &Y C AM &T D AT &M Answer A Marks 1 Unit 1 Id Question ______is used to control various modules in the system A Control Bus B Data Bus C Address Bus D All of these Answer A Marks 1 Unit 1 Id Question The disadvantage of single bus structure over multi bus structure is _____ A Propagation delay B Bottle neck because of bus capacity C Both A and B D Neither A nor B Answer C Marks 1 Unit 1 Id Question _____ provide path for moving data among system modules A Control Bus B Data Bus C Address Bus D All of these Answer B Marks 1 Unit 1 Id Question Microcontroller is the example of _____ architecture. -

Computer Development at the National Bureau of Standards

Computer Development at the National Bureau of Standards The first fully operational stored-program electronic individual computations could be performed at elec- computer in the United States was built at the National tronic speed, but the instructions (the program) that Bureau of Standards. The Standards Electronic drove these computations could not be modified and Automatic Computer (SEAC) [1] (Fig. 1.) began useful sequenced at the same electronic speed as the computa- computation in May 1950. The stored program was held tions. Other early computers in academia, government, in the machine’s internal memory where the machine and industry, such as Edvac, Ordvac, Illiac I, the Von itself could modify it for successive stages of a compu- Neumann IAS computer, and the IBM 701, would not tation. This made a dramatic increase in the power of begin productive operation until 1952. programming. In 1947, the U.S. Bureau of the Census, in coopera- Although originally intended as an “interim” com- tion with the Departments of the Army and Air Force, puter, SEAC had a productive life of 14 years, with a decided to contract with Eckert and Mauchly, who had profound effect on all U.S. Government computing, the developed the ENIAC, to create a computer that extension of the use of computers into previously would have an internally stored program which unknown applications, and the further development of could be run at electronic speeds. Because of a demon- computing machines in industry and academia. strated competence in designing electronic components, In earlier developments, the possibility of doing the National Bureau of Standards was asked to be electronic computation had been demonstrated by technical monitor of the contract that was issued, Atanasoff at Iowa State University in 1937. -

The State of Digital Computer Technology in Europe, 1961

This report indicates the level of computer development and application in each of the thirty countries of Europe, most of which were recently visited by the author The State Of Digital Computer Technology In Europe By NELSON M. BLACHMAN Digital computers are now in use in practically every Communist Countries country in Europe, though in some there are still very few U. S. S.R. A very thorough account of Soviet com- and these are of foreign manufacture. Such machines have puter work is given in the report edited by Willis Ware [3]. been built in sixteen European countries, of which seven To Ware's collection of Russian machines can be added a are producing them commercially. The map above shows computer at the Moscow Power Institute, a school for the the computer geography of Europe and the Near East. It is training of heavy-current electrical engineers (Figure 1). somewhat difficult to rank the countries on a one-dimen- It is described as having a speed of 25,000 fixed-point sional scale both because of the many-faceted nature of the operations or five to seven thousand floating-point oper- computer field and because their populations differ widely ations per second, a word length of 20 or 40 bits, and a in size. Nevertheh~ss, Great Britain clearly comes first 4096-word ferrite-core memory, supplemented by a fixed (after the U. S.). She is followed by (West) Germany, the 256-word store on paper printed with condensers plus a U. S. S. R., France, and Japan. Much useful information on 50,000-word magnetic-tape store. -

Golden Yearbook

Golden Yearbook Golden Yearbook Stories from graduates of the 1930s to the 1960s Foreword from the Vice-Chancellor and Principal ���������������������������������������������������������5 Message from the Chancellor ��������������������������������7 — Timeline of significant events at the University of Sydney �������������������������������������8 — The 1930s The Great Depression ������������������������������������������ 13 Graduates of the 1930s ���������������������������������������� 14 — The 1940s Australia at war ��������������������������������������������������� 21 Graduates of the 1940s ����������������������������������������22 — The 1950s Populate or perish ���������������������������������������������� 47 Graduates of the 1950s ����������������������������������������48 — The 1960s Activism and protest ������������������������������������������155 Graduates of the 1960s ���������������������������������������156 — What will tomorrow bring? ��������������������������������� 247 The University of Sydney today ���������������������������248 — Index ����������������������������������������������������������������250 Glossary ����������������������������������������������������������� 252 Produced by Marketing and Communications, the University of Sydney, December 2016. Disclaimer: The content of this publication includes edited versions of original contributions by University of Sydney alumni and relevant associated content produced by the University. The views and opinions expressed are those of the alumni contributors and do -

Parallel Computing

Lecture 1: Computer Organization 1 Outline • Overview of parallel computing • Overview of computer organization – Intel 8086 architecture • Implicit parallelism • von Neumann bottleneck • Cache memory – Writing cache-friendly code 2 Why parallel computing • Solving an × linear system Ax=b by using Gaussian elimination takes ≈ flops. 1 • On Core i7 975 @ 4.0 GHz,3 which is capable of about 3 60-70 Gigaflops flops time 1000 3.3×108 0.006 seconds 1000000 3.3×1017 57.9 days 3 What is parallel computing? • Serial computing • Parallel computing https://computing.llnl.gov/tutorials/parallel_comp 4 Milestones in Computer Architecture • Analytic engine (mechanical device), 1833 – Forerunner of modern digital computer, Charles Babbage (1792-1871) at University of Cambridge • Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer (ENIAC), 1946 – Presper Eckert and John Mauchly at the University of Pennsylvania – The first, completely electronic, operational, general-purpose analytical calculator. 30 tons, 72 square meters, 200KW. – Read in 120 cards per minute, Addition took 200µs, Division took 6 ms. • IAS machine, 1952 – John von Neumann at Princeton’s Institute of Advanced Studies (IAS) – Program could be represented in digit form in the computer memory, along with data. Arithmetic could be implemented using binary numbers – Most current machines use this design • Transistors was invented at Bell Labs in 1948 by J. Bardeen, W. Brattain and W. Shockley. • PDP-1, 1960, DEC – First minicomputer (transistorized computer) • PDP-8, 1965, DEC – A single bus -

ITER: the Way for Australian Energy Research?

The University of Sydney School of Physics 6 0 0 ITER: the Way for Australian 2 Energy Research? Physics Alumnus talks up the Future of Fusion November “World Energy demand will Amongst the many different energy sources double in the next 50 years on our planet, Dr Green calls nuclear fusion the – which is frightening,” ‘philosopher’s stone of energy’ – an energy source s a i d D r B a r r y G r e e n , that could potentially do everything we want. School of Physics alumnus Appropriate fuel is abundant, with the hydrogen and Research Program isotope deuterium and the element lithium able to Officer, Fusion Association be derived primarily from seawater (as an indication, Agreements, Directorate- the deuterium in 45 litres water and the lithium General for Research at the in one laptop battery would supply the fuel for European Commisison in one person’s personal electricity use for 30 years). Brussels, at a recent School Fusion has ‘little environmental impact or safety research seminar. concerns’: there are no greenhouse gas emissions, “The availability of and unlike nuclear fission there are no runaway cheap energy sources is a nuclear processes. The fusion reactions produce no thing of the past, and we radioactive ash waste, though a fusion energy plant’s Artists’s impression of the ITER fusion reactor have to be concerned about structure would become radioactive – Dr Green the environmental impacts reckoned that the material could be processed and of energy production.” recycled within around 100 years. Dr Green was speaking in Sydney during his nation-wide tour to promote ITER, the massive Despite all these benefits, international research collaboration to build a fusion-energy future is still a long an experimental device to demonstrate the way off. -

Open PDF in New Window

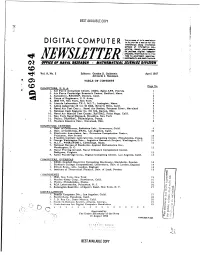

BEST AVAILABLE COPY i The pur'pose of this DIGITAL COMPUTER Itop*"°a""-'"""neesietter' YNEWSLETTER . W OFFICf OF NIVAM RUSEARCMI • MATNEMWTICAL SCIENCES DIVISION Vol. 9, No. 2 Editors: Gordon D. Goldstein April 1957 Albrecht J. Neumann TABLE OF CONTENTS It o Page No. W- COMPUTERS. U. S. A. "1.Air Force Armament Center, ARDC, Eglin AFB, Florida 1 2. Air Force Cambridge Research Center, Bedford, Mass. 1 3. Autonetics, RECOMP, Downey, Calif. 2 4. Corps of Engineers, U. S. Army 2 5. IBM 709. New York, New York 3 6. Lincoln Laboratory TX-2, M.I.T., Lexington, Mass. 4 7. Litton Industries 20 and 40 DDA, Beverly Hills, Calif. 5 8. Naval Air Test Centcr, Naval Air Station, Patuxent River, Maryland 5 9. National Cash Register Co. NC 304, Dayton, Ohio 6 10. Naval Air Missile Test Center, RAYDAC, Point Mugu, Calif. 7 11. New York Naval Shipyard, Brooklyn, New York 7 12. Philco, TRANSAC. Philadelphia, Penna. 7 13. Western Reserve Univ., Cleveland, Ohio 8 COMPUTING CENTERS I. Univ. of California, Radiation Lab., Livermore, Calif. 9 2. Univ. of California, SWAC, Los Angeles, Calif. 10 3. Electronic Associates, Inc., Princeton Computation Center, Princeton, New Jersey 10 4. Franklin Institute Laboratories, Computing Center, Philadelphia, Penna. 11 5. George Washington Univ., Logistics Research Project, Washington, D. C. 11 6. M.I.T., WHIRLWIND I, Cambridge, Mass. 12 7. National Bureau of Standards, Applied Mathematics Div., Washington, D.C. 12 8. Naval Proving Ground, Naval Ordnance Computation Center, Dahlgren, Virgin-.a 12 9. Ramo Wooldridge Corp., Digital Computing Center, Los Angeles, Calif. -

6.823 Computer System Architecture

6.823 Computer System Architecture Instructors: Daniel Sanchez and Joel Emer TA: Hyun Ryong (Ryan) Lee What you’ll understand after The processor you taking 6.823 built in 6.004 September 8, 2021 MIT 6.823 Fall 2021 L01-1 Computing devices then… September 8, 2021 MIT 6.823 Fall 2021 L01-2 Computing devices now September 8, 2021 MIT 6.823 Fall 2021 L01-3 A journey through this space • What do computer architects actually do? • Illustrate via historical examples – Early days: ENIAC, EDVAC, and EDSAC – Arrival of IBM 650 and then IBM 360 – Seymour Cray – CDC 6600, Cray 1 – Microprocessors and PCs – Multicores – Cell phones • Focus on ideas, mechanisms, and principles, especially those that have withstood the test of time September 8, 2021 MIT 6.823 Fall 2021 L01-4 Abstraction layers Application Algorithm Parallel computing, Programming Language specialization, Original Operating System/Virtual Machine security, … domain of the Instruction Set Architecture (ISA) Domain of computer Microarchitecture computer architect architecture (‘90s) (‘50s-‘80s) Register-Transfer Level (RTL) Circuits Reliability, power Devices Expansion of Physics computer architecture, mid- 2000s onward. September 8, 2021 MIT 6.823 Fall 2021 L01-5 Computer Architecture is the design of abstraction layers • What do abstraction layers provide? – Environmental stability within generation – Environmental stability across generations – Consistency across a large number of units • What are the consequences? – Encouragement to create reusable foundations: • Toolchains, operating systems, libraries – Enticement for application innovation September 8, 2021 MIT 6.823 Fall 2021 L01-6 Technology is the dominant factor in computer design Technology Transistors Computers Integrated circuits VLSI (initially) Flash memories, … Technology Core memories Computers Magnetic tapes Disks Technology ROMs, RAMs VLSI Computers Packaging Low Power September 8, 2021 MIT 6.823 Fall 2021 L01-7 But Software.. -

P the Pioneers and Their Computers

The Videotape Sources: The Pioneers and their Computers • Lectures at The Compp,uter Museum, Marlboro, MA, September 1979-1983 • Goal: Capture data at the source • The first 4: Atanasoff (ABC), Zuse, Hopper (IBM/Harvard), Grosch (IBM), Stibitz (BTL) • Flowers (Colossus) • ENIAC: Eckert, Mauchley, Burks • Wilkes (EDSAC … LEO), Edwards (Manchester), Wilkinson (NPL ACE), Huskey (SWAC), Rajchman (IAS), Forrester (MIT) What did it feel like then? • What were th e comput ers? • Why did their inventors build them? • What materials (technology) did they build from? • What were their speed and memory size specs? • How did they work? • How were they used or programmed? • What were they used for? • What did each contribute to future computing? • What were the by-products? and alumni/ae? The “classic” five boxes of a stored ppgrogram dig ital comp uter Memory M Central Input Output Control I O CC Central Arithmetic CA How was programming done before programming languages and O/Ss? • ENIAC was programmed by routing control pulse cables f ormi ng th e “ program count er” • Clippinger and von Neumann made “function codes” for the tables of ENIAC • Kilburn at Manchester ran the first 17 word program • Wilkes, Wheeler, and Gill wrote the first book on programmiidbBbbIiSiing, reprinted by Babbage Institute Series • Parallel versus Serial • Pre-programming languages and operating systems • Big idea: compatibility for program investment – EDSAC was transferred to Leo – The IAS Computers built at Universities Time Line of First Computers Year 1935 1940 1945 1950 1955 ••••• BTL ---------o o o o Zuse ----------------o Atanasoff ------------------o IBM ASCC,SSEC ------------o-----------o >CPC ENIAC ?--------------o EDVAC s------------------o UNIVAC I IAS --?s------------o Colossus -------?---?----o Manchester ?--------o ?>Ferranti EDSAC ?-----------o ?>Leo ACE ?--------------o ?>DEUCE Whirl wi nd SEAC & SWAC ENIAC Project Time Line & Descendants IBM 701, Philco S2000, ERA..