The Selected Works of Gordon Tullock

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What's Your Learning Style?

What’s Your Learning Style? Different people have different learning styles. Style refers to a student’s specific learning preferences and actions. One student may learn more effectively from listening to the instructor. Another learns more effectively from reading the textbook, while another student benefits most from charts, graphs, and images the instructor presents during a lecture. Learning style is important in college. Each different style, described later in more detail, has certain advantages and disadvantages compared with other styles. None is “right” or “wrong.” You can learn to use your own style more effectively. College instructors also have different teaching styles, which may or may not match up well with your learning style. Although you may personally learn best from a certain style of teaching, you cannot expect that your instructors will use exactly the style that is best for you. Therefore it is important to know how to adapt to teaching styles used in college. Different systems have been used to describe the different ways in which people learn. Some describe the differences between how extroverts (outgoing, gregarious, social people) and introverts (quiet, private, contemplative people) learn. Some divide people into “thinkers” and “feelers.” A popular theory of different learning styles is Howard Gardner’s “multiple intelligences,” based on eight different types of intelligence: 1. Verbal (prefers words) 2. Logical (prefers math and logical problem solving) 3. Visual (prefers images and spatial relationships) 4. Kinesthetic (prefers body movements and doing) 5. Rhythmic (prefers music, rhymes) 6. Interpersonal (prefers group work) 7. Intrapersonal (prefers introspection and independence) 8. Naturalist (prefers nature, natural categories) The multiple intelligences approach recognizes that different people have different ways, or combinations of ways, of relating to the world. -

Retrocausality

RETROCAUSALITY By Ian J. Courter Revision #4 © 2015 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. NO PORTION OF THIS SCRIPT MAY BE PERFORMED, PUBLISHED, REPRODUCED, SOLD, OR DISTRIBUTED BY ANY MEANS OR QUOTED OR PUBLISHED IN ANY MEDIUM, INCLUDING ANY WEBSITE,WITHOUT PRIOR WRITTEN CONSENT. [email protected] FADE IN: EXT. MESOPOTAMIA - BABYLON (2250 B.C.) - NIGHT SUPER: Babylon - 2250 B.C. Soft moonlight shines on narrow, dusty, and deserted streets winding among mud-brick buildings. Scattered torches flicker in time with the WHISPER of a gentle wind as insects BUZZ. At tree-top level, there is a SPARK as a flat-black, rugby ball-sized PROBE appears in mid-air, indistinct and nearly invisible. After a moment, it glides away silently. EXT. ISHTAR GATE - CONTINUOUS The probe hovers, bobbing ever so slightly in the breeze. PROBE POV - THE GATE In night vision green. Lines of laser light rapidly criss- cross the gate from one end to the other. BACK TO SCENE No visible lights as the probe glides over the gate and stops on the other side. INT. RESEARCH FACILITY - WAREHOUSE (PRESENT) - DAY SUPER: Present Huge interior space with old, dusty equipment in the corners. Bright lights shine on a large, metal ring lying in the center. A thick cable extends from it to a shipping container- sized metal box with a large digital control panel. On a raised platform with a railing, stereotypical SCIENTISTS in lab coats cluster around large window pane-thin monitors. SIMON JACOBS (30), thin and geeky, works at a console. MARTIN GALANG (50), gray-haired and tall in a designer suit, strides up to the console. -

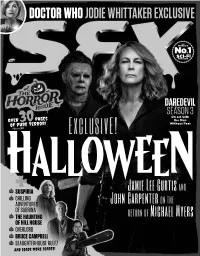

SFX’S Horror Columnist Peers Into If You’Re New to the Netflix Catherine Zeta-Jones Movie

DOCTOR WHO JODIE WHITTAKER EXCLUSIVE SCI-FI 306 DAREDEVIL SEASON 3 On set with Over 30 pages the Man of pure terror! Without Fear featuring EXCLUSIVE! HALLOWEEN Jamie Lee Curtis and SUSPIRIA CHILLING John Carpenter on the ADVENTURES OF SABRINA return of Michael Myers THE HAUNTING OF HILL HOUSE OVERLORD BRUCE CAMPBELL SLAUGHTERHOUSE RULEZ AND LOADS MORE SCARES! ISSUE 306 NOVEMBER Contents2018 34 56 61 68 HALLOWEEN CHILLING DRACUL DOCTOR WHO Jamie Lee Curtis and John ADVENTURES Bram Stoker’s great-grandson We speak to the new Time Lord Carpenter tell us about new OF SABRINA unearths the iconic vamp for Jodie Whittaker about series 11 Michael Myers sightings in Remember Melissa Joan Hart another toothsome tale. and her Heroes & Inspirations. Haddonfield. That place really playing the teenage witch on CITV needs a Neighbourhood Watch. in the ’90s? Well this version is And a can of pepper spray. nothing like that. 62 74 OVERLORD TADE THOMPSON A WW2 zombie horror from the The award-winning Rosewater 48 56 JJ Abrams stable and it’s not a author tells us all about his THE HAUNTING OF Cloverfield movie? brilliant Nigeria-set novel. HILL HOUSE Shirley Jackson’s horror classic gets a new Netflix treatment. 66 76 Who knows, it might just be better PENNY DREADFUL DAREDEVIL than the 1999 Liam Neeson/ SFX’s horror columnist peers into If you’re new to the Netflix Catherine Zeta-Jones movie. her crystal ball to pick out the superhero shows, this third season Fingers crossed! hottest upcoming scares. is probably a bad place to start. -

To Download Conference Program

ACMI & THE AUSTRALIAN RESEARCH COUNCIL PRESENT 6–8 December 9am–7pm Join 50 leading experts as they unmask the critical thinking behind superheroes from comics to film, TV and videogames #acmisuperheroes While at the Superheroes Beyond Welcome to the conference come and experiencE... Conference! Superheroes are transmedia, transcultural, and transhistorical icons, and yet discussions of these a VR experience at Screen Worlds at ACMI caped crusaders often fixate on familiar examples. This conference will go beyond out-dated definitions of superheroes. Over the next three days we will unmask international examples, WE’VE BEEN WAITING FOR YOU! SuperHeroes: Realities Collide examine superheroes beyond the comic book page, identify historical antecedents, consider real is a trip to an alternative comic dimension in room-scale Virtual world examples of superheroism, and explore heroes whose secret identities are not cisgender men. Reality. The City of Melbourne needs you to create your own unique character, choose powers and abilities to transform into a This conference is part of the larger Superheroes & Me Linkage research project funded by the superhero who will protect us from a dangerous comic contagion. Australian Research Council. Partners in this project included Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne University, National University of Singapore, and our industry partner ACMI. While at Created in a unique collaboration between Swinburne University of ACMI please make sure to visit some of the other project outcomes including the newly curated Technology, celebrated technology artist Stuart Campbell aka Cleverman: The Exhibition, which goes behind the scenes of the ground-breaking Australian superhero SUTU and award-wining VR studio VISITOR. -

David Ramsey Ç”Μå½± ĸ²È¡Œ (Ť§Å…¨)

David Ramsey 电影 串行 (大全) Dead to Rights https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/dead-to-rights-16555590/actors Suicide Squad https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/suicide-squad-16636526/actors The Secret Origin of Felicity https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-secret-origin-of-felicity-smoak-18416478/actors Smoak Legacies https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/legacies-21075036/actors Invasion! https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/invasion%21-28518213/actors Legacy https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/legacy-28517940/actors The Odyssey https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-odyssey-16639693/actors Three Ghosts https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/three-ghosts-16640101/actors Brotherhood https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/brotherhood-21484189/actors Lone Gunmen https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/lone-gunmen-9023621/actors Muse of Fire https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/muse-of-fire-16609655/actors Kapiushon https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/kapiushon-30634955/actors Unfinished Business https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/unfinished-business-16644267/actors Identity https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/identity-16577364/actors Betrayal https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/betrayal-17622803/actors Keep Your Enemies Closer https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/keep-your-enemies-closer-16586458/actors The Calm https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-calm-18285639/actors Vertigo https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/vertigo-16645902/actors -

Collective of Heroes: Arrow's Move Toward a Posthuman Superhero Fantasy

St. Cloud State University theRepository at St. Cloud State Culminating Projects in English Department of English 12-2016 Collective of Heroes: Arrow’s Move Toward a Posthuman Superhero Fantasy Alyssa G. Kilbourn St. Cloud State University Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/engl_etds Recommended Citation Kilbourn, Alyssa G., "Collective of Heroes: Arrow’s Move Toward a Posthuman Superhero Fantasy" (2016). Culminating Projects in English. 73. https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/engl_etds/73 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at theRepository at St. Cloud State. It has been accepted for inclusion in Culminating Projects in English by an authorized administrator of theRepository at St. Cloud State. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Collective of Heroes: Arrow’s Move Toward a Posthuman Superhero Fantasy by Alyssa Grace Kilbourn A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of St. Cloud State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Rhetoric and Writing December, 2016 Thesis Committee: James Heiman, Chairperson Matthew Barton Jennifer Tuder 2 Abstract Since 9/11, superheroes have become a popular medium for storytelling, so much so that popular culture is inundated with the narratives. More recently, the superhero narrative has moved from cinema to television, which allows for the narratives to address more pressing cultural concerns in a more immediate fashion. Furthermore, millions of viewers perpetuate the televised narratives because they resonate with the values and stories in the shows. Through Fantasy Theme Analysis, this project examines the audience values within the Arrow’s superhero fantasy and the influence of posthumanism on the show’s superhero fantasy. -

Petition for Cancelation

Trademark Trial and Appeal Board Electronic Filing System. http://estta.uspto.gov ESTTA Tracking number: ESTTA743501 Filing date: 04/30/2016 IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD Petition for Cancellation Notice is hereby given that the following party requests to cancel indicated registration. Petitioner Information Name Organization for Transformative Works, Inc. Entity Corporation Citizenship Delaware Address 2576 Broadway #119 New York City, NY 10025 UNITED STATES Correspondence Heidi Tandy information Legal Committee Member Organization for Transformative Works, Inc. 1691 Michigan Ave Suite 360 Miami Beach, FL 33139 UNITED STATES [email protected] Phone:3059262227 Registration Subject to Cancellation Registration No 4863676 Registration date 12/01/2015 Registrant Power I Productions LLC 163 West 18th Street #1B New York, NY 10011 UNITED STATES Goods/Services Subject to Cancellation Class 041. First Use: 2013/12/01 First Use In Commerce: 2015/08/01 All goods and services in the class are cancelled, namely: Entertainment services, namely, an ongo- ing series featuring documentary films featuring modern cultural phenomena provided through the in- ternet and movie theaters; Entertainment services, namely, displaying a series of films; Entertain- mentservices, namely, providing a web site featuring photographic and prose presentations featuring modern cultural phenomena; Entertainment services, namely, storytelling Grounds for Cancellation The mark is merely descriptive Trademark Act Sections 14(1) and 2(e)(1) The mark is or has become generic Trademark Act Section 14(3), or Section 23 if on Supplemental Register Attachments Fandom_Generic_Petition.pdf(2202166 bytes ) Fandom Appendix pt 1.pdf(4769247 bytes ) Fandom Appendix pt 2.pdf(4885778 bytes ) Fandom Appendix pt 3.pdf(3243682 bytes ) Certificate of Service The undersigned hereby certifies that a copy of this paper has been served upon all parties, at their address record by First Class Mail on this date. -

The Scientist Magazine®

Name That Metabolite! | The Scientist Magazine® http://www.the-scientist.com/?articles.view/articleNo/36135/titl... Sign In or Register NN e e ww s s MM a a g g a a z z i i n n e e MM u u l l t t i i mm e e d d i i a a SS uu bb j j ee cc t t ss SS uu r r vv ee yy ss CC a a r r ee ee r r s s Search The Scientist » Magazine » Lab Tools Follow The Scientist Name That Metabolite! A guided tour through the metabolome By Jeffrey M. Perkel | July 1, 2013 0 Comments Like 0 0 Link this Stumble Tweet this he suffix ‘-omics’ is synonymous with Big T Data. It’s simply a given that when one researcher publishes an omics data set, be it genomic, transcriptomic, or proteomic, other researchers will be able to take a crack at it, too. Metabolomics data are no different. Researchers regularly report on dysregulated metabolites in disease and development. In one 2012 study, Scripps Research Institute metabolomics expert Stay Connected with The Scientist Gary Siuzdak, with his then-postdoc Gary Patti, The Scientist Magazine used mass spectrometry to identify dysregulated The Scientist Careers metabolites in a rat model of neuropathic pain. Of Neuroscience Research Techniques the tens of thousands of spectral peaks they Genetic Research Techniques examined, 733 were “significantly dysregulated” compared to control animals. The researchers Cell Culture Techniques eventually homed in on sphingomyelin-ceramide Microbiology and Immunology metabolism, one of the pathways these peaks Cancer Research and Technology represented (Nat Chem Biol, 8:232-34, 2012). -

Thursday (Mar 21) | Track 1 : 12:00 PM- 2:00 PM

Thursday (Mar 21) | Track 1 : 12:00 PM- 2:00 PM 1.29 Teaching the Humanities Online (Workshop) Chair: Susan Ko, Lehman College-CUNY Chair: Richard Schumaker, City University of New York Location: Eastern Shore 1 Pedagogy & Professional 1.31 Lessons from Practice: Creating and Implementing a Successful Learning Community (Workshop) Chair: Terry Novak, Johnson and Wales University Location: Eastern Shore 3 Pedagogy & Professional 1.34 Undergraduate Research Forum and Workshop (Part 1) (Poster Presentations) Chair: Jennifer Mdurvwa, SUNY University at Buffalo Chair: Claire Sommers, Graduate Center, CUNY Location: Bella Vista A (Media Equipped) Pedagogy & Professional "The Role of the Sapphic Gaze in Post-Franco Spanish Lesbian Literature" Leah Headley, Hendrix College "Social Acceptance and Heroism in the Táin " Mikaela Schulz, SUNY University at Buffalo "Né maschile né femminile: come la lingua di genere neutro si accorda con la lingua italiana" Deion Dresser, Georgetown University "Woolf, Joyce, and Desire: Queering the Sexual Epiphany" Kayla Marasia, Washington and Jefferson College "Echoes and Poetry, Mosques and Modernity: A Passage to a Muslim-Indian Consciousness" Suna Cha, Georgetown University "Nick Joaquin’s Tropical Gothic and Why We Need Philippine English Literature" Megan Conley, University of Maryland College Park "Crossing the Linguistic Borderline: A Literary Translation of Shu Ting’s “The Last Elegy”" Yuxin Wen, University of Pennsylvania "World Languages at Rutgers: A Web Multimedia Project" Han Yan, Rutgers University "Interactions Between the Chinese and the Jewish Refugees in Shanghai During World War II" Qingyang Zhou, University of Pennsylvania "“A Vast Sum of Conditions”: Sexual Plot and Erotic Description in George Eliot’s Mill on the Floss" Derek Willie, University of Pennsylvania "Decoding Cultural Representations and Relations in Virtual Reality " Brenna Zanghi, University at Buffalo "D.H. -

00001. Rugby Pass Live 1 00002. Rugby Pass Live 2 00003

00001. RUGBY PASS LIVE 1 00002. RUGBY PASS LIVE 2 00003. RUGBY PASS LIVE 3 00004. RUGBY PASS LIVE 4 00005. RUGBY PASS LIVE 5 00006. RUGBY PASS LIVE 6 00007. RUGBY PASS LIVE 7 00008. RUGBY PASS LIVE 8 00009. RUGBY PASS LIVE 9 00010. RUGBY PASS LIVE 10 00011. NFL GAMEPASS 1 00012. NFL GAMEPASS 2 00013. NFL GAMEPASS 3 00014. NFL GAMEPASS 4 00015. NFL GAMEPASS 5 00016. NFL GAMEPASS 6 00017. NFL GAMEPASS 7 00018. NFL GAMEPASS 8 00019. NFL GAMEPASS 9 00020. NFL GAMEPASS 10 00021. NFL GAMEPASS 11 00022. NFL GAMEPASS 12 00023. NFL GAMEPASS 13 00024. NFL GAMEPASS 14 00025. NFL GAMEPASS 15 00026. NFL GAMEPASS 16 00027. 24 KITCHEN (PT) 00028. AFRO MUSIC (PT) 00029. AMC HD (PT) 00030. AXN HD (PT) 00031. AXN WHITE HD (PT) 00032. BBC ENTERTAINMENT (PT) 00033. BBC WORLD NEWS (PT) 00034. BLOOMBERG (PT) 00035. BTV 1 FHD (PT) 00036. BTV 1 HD (PT) 00037. CACA E PESCA (PT) 00038. CBS REALITY (PT) 00039. CINEMUNDO (PT) 00040. CM TV FHD (PT) 00041. DISCOVERY CHANNEL (PT) 00042. DISNEY JUNIOR (PT) 00043. E! ENTERTAINMENT(PT) 00044. EURONEWS (PT) 00045. EUROSPORT 1 (PT) 00046. EUROSPORT 2 (PT) 00047. FOX (PT) 00048. FOX COMEDY (PT) 00049. FOX CRIME (PT) 00050. FOX MOVIES (PT) 00051. GLOBO PORTUGAL (PT) 00052. GLOBO PREMIUM (PT) 00053. HISTORIA (PT) 00054. HOLLYWOOD (PT) 00055. MCM POP (PT) 00056. NATGEO WILD (PT) 00057. NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC HD (PT) 00058. NICKJR (PT) 00059. ODISSEIA (PT) 00060. PFC (PT) 00061. PORTO CANAL (PT) 00062. PT-TPAINTERNACIONAL (PT) 00063. RECORD NEWS (PT) 00064. -

Ebook > Arrow Season 2, Episode 8 the Scientist Trivia Quiz Book

JHCSIIF0VT > Arrow Season 2, Episode 8 The Scientist Trivia Quiz Book # Kindle A rrow Season 2, Episode 8 Th e Scientist Trivia Quiz Book By Trivia Quiz Book CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. Paperback. Book Condition: New. This item is printed on demand. Paperback. 102 pages. Dimensions: 9.0in. x 6.0in. x 0.2in.Arrow Season 2, Episode 8 The Scientist Trivia Quiz Book is the latest title to test your knowledge in the Trivia Quiz Book series. All of our trivia quiz books were written to keep you entertained while challenging you to some tough trivia questions on Arrow Season 2, Episode 8 The Scientist. The paperback edition makes a great gift for anyone who is a fan of Arrow Season 2, Episode 8 The Scientist. Our unique Arrow Season 2, Episode 8 The Scientist Trivia Quiz Book will give you a variety of questions on Arrow Season 2, Episode 8 The Scientist. (arrow, arrow tv, arrow tv series, green arrow, dc arrow, super hero arrow, arrow tv show) Each of our trivia quiz books is loaded with questions to test your knowledge. All questions pages are loaded with pictures and graphics to keep you entertained while you learn. If you are buying the Kindle edition you are in for a real treat! Our Arrow Season 2, Episode 8 The Scientist Trivia Quiz Book is interactive! What that means is you... READ ONLINE [ 7.42 MB ] Reviews The book is simple in read through safer to understand. I could comprehended everything out of this published e pdf. I discovered this book from my i and dad advised this pdf to learn. -

The Scientist and American Cinema: Trends and Case Studies

The Scientist and American Cinema: Trends and Case Studies Ciara Wardlow Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Prerequisite for Honors in Cinema and Media Studies under the advisement of Dr. N. Adriana Knouf April 2019 © 2019 Ciara Wardlow TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………………… 3 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………….. 4 Chapter 1: A Historical Overview of Scientists in American Film……………………… 12 Chapter 2: Space Science and Cinema…………………………………………………………… 83 Chapter 3: Heroic Renegades and “Strange Birds”: Scientist Biopics……………….. 114 Chapter 4: The Scientist Goes to the Remakes: The Thing and The Fly……………..156 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………………………..198 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………………………. 202 2 Acknowledgements To begin, I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Professor Adriana Knouf, for guiding me throughout this process, as well as Professor Maurizio Viano, who advised the Fall 2017 independent study that served as the basis for chapter 3. My deepest gratitude to the Cinema and Media Studies department at Wellesley for teaching me how to dissect a film, and to the publications Film School Rejects and The Hollywood Reporter's Heat Vision website, for giving me the opportunity to further evolve those skills while reaching an audience. I would also like to thank my friends and family for their support and encouragement. In particular, I would like to acknowledge my father, Jesse Wardlow, for never checking MPAA ratings before taking me to see whatever sci-fi movie was playing that week, and my mother, Brid Wardlow, for not stopping him. I genuinely think I am a more interesting person today for having seen The Matrix at age six. Lastly, I would like to give a special shout-out to caffeine, for keeping me going.