Assessing a Weimar Chancellor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abstammungslinien-Entwurf Zur Grafik 3

Abstammungslinien-Entwurf zur Grafik 3: Stand: 5. Juni 2010 Zusammenstellung: Arndt Richter, München am 23.12.2016 ergänzt von Wolfgang Bernhardt, Hoyerswerda Diese Zusammenstellung soll linienmäßig noch erweitert werden. Ergänzungswünsche erbeten an: [email protected] Quellen: AL Anna von Mohl, (Arndt Richter, handschriftlich) AL Kinder Rösch, (Siegfried Rösch, handschriftlich) AL Max Planck (Arndt Richter, WORD-AL) AL v.Weizsäcker-v.Graevenitz, Berlin 1992 ( F. W. Euler) AL Wilhelm Hauff: AT berühmter Deutscher, Bd. 2. und Ergäzung Bd. 4. Zu Seite 46 f.: Deutsches Familienarchiv (DFA) Bd. 58, 1973 (Gmelin-Stammliste!): Zu Seite 56 f.: F. W. Euler: „Alfred v. Tirpitz und seine Ahnen“; in: AfS (1989), 55. Jg., H. 114, S. 81-100). Zu Seite 57 f: Gero v.Wilcke: Caroline Böhmer und ihre Tochter – Zur Genealogie von Schellings erster Frau; in: AfS (1975), H.57, S.39-50; und Friedrich v. Klocke: Familie und Volk (1955, S. 169). ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Abstammungslinien A (zur Grafik 3) (AvM 10170/1) Aus der AL Anna von Mohl (Zusammenstellung Arndt Richter, München) entnommen: Die Ahnen-Nrn. beziehen sich hier daher auf die AL Anna von Mohl als Probanden. Quelle zur Dynastenabstammung: Deutsches Geschlechterbuch (DGB) Bd. 170 = Schwäbisches Geschlechterbuch, 9. Band, zur Famlie Dreher, Anhang B (AL Dreher/Volland), bearbeitet von D. Dr. Otto Beuttenmüller). 20342 v. Wirtemberg (Württemberg), Graf Eberhard V., „der Junge“, * 23.8.1388, + Waiblingen 2.7.1419, □ Stuttgart; o-o (uneheliche Verbindung) 20343 v. Dagersheim, Agnes, * (Stuttgart) um 1399, das „v.“ ist Herkunftsbezeichnung, die bereits bei Ihrem Vater üblich war; ihre Eltern waren Werner v. Dagersheim, Ratsherr zu Stuttgart 1402/31, und Katharina Machtolf (war seine 2. -

Power Distribution in the Weimar Reichstag in 1919-1933

Power Distribution in the Weimar Reichstag in 1919-1933 Fuad Aleskerov1, Manfred J. Holler2 and Rita Kamalova3 Abstract: ................................................................................................................................................2 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................................2 2. The Weimar Germany 1919-1933: A brief history of socio-economic performance .......................3 3. Political system..................................................................................................................................4 3.2 Electoral system for the Reichstag ..................................................................................................6 3.3 Political parties ................................................................................................................................6 3.3.1 The Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD).....................................................................7 3.3.2 The Communist Party of Germany (Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands – KPD)...............8 3.3.3 The German Democratic Party (Deutsche Demokratische Partei – DDP)...............................9 3.3.4 The Centre Party (Deutsche Zentrumspartei – Zentrum) .......................................................10 3.3.5 The German People's Party (Deutsche Volkspartei – DVP) ..................................................10 3.3.6 German-National People's Party (Deutsche -

The German Currency Crisis of 1930

Why the French said “non”: Creditor-debtor politics and the German financial crises of 1930 and 1931 Simon Banholzer, University of Zurich Tobias Straumann, University of Zurich1 First draft July, 2015 Abstract Why did France delay the Hoover moratorium in June of 1931? In many accounts, this policy is explained by Germany’s reluctance to respond to the French gestures of reconciliation in early 1931 and by the announcement to form a customs union with Austria in March of 1931. The analysis of the German currency crisis in the fall of 1930 suggests otherwise. Already then, the French government did not cooperate in order to help the Brüning government to overcome the crisis. On the contrary, it delayed the negotiation process, thus acerbating the crisis. But unlike in 1931, France did not have the veto power to obstruct the rescue. 1 Corresponding author: Tobias Straumann, Department of Economics (Economic History), Zürichbergstrasse 14, CH–8032 Zürich, Switzerland, [email protected] 1 1. Introduction The German crisis of 1931 is one the crucial moments in the course of the global slump. It led to a global liquidity crisis, bringing down the British pound and a number of other currencies and causing a banking crisis in the United States and elsewhere. The economic turmoil also had negative political consequences. The legitimacy of the Weimar Republic further eroded, Chancellor Heinrich Brüning became even more unpopular. The British historian Arnold Toynbee quite rightly dubbed the year 1931 “annus terribilis”. As with any financial crisis, the fundamental cause was a conflict of interests and a climate of mistrust between the creditors and the debtor. -

Martin Luther and Women: from the Dual Perspective of Theory and Practice

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2019-06-27 Martin Luther and Women: From the Dual Perspective of Theory and Practice Jurgens, Laura Kathryn Jurgens, L. K. (2019). Martin Luther and Women: From the Dual Perspective of Theory and Practice (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/110570 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Martin Luther and Women: From the Dual Perspective of Theory and Practice by Laura Kathryn Jurgens A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN RELIGIOUS STUDIES CALGARY, ALBERTA JUNE, 2019 © Laura Kathryn Jurgens 2019 ii Abstract This thesis argues that Martin Luther did not enforce his own strict theological convictions about women and their nature when he personally corresponded with women throughout his daily life. This becomes clear with Luther’s interactions with female family members and Reformation women. With these personal encounters, he did not maintain his theological attitudes and often made exceptions to his own theology for such exceptional or influential women. Luther also did not enforce his strict theology throughout his pastoral care where he treated both men and women respectfully and equally. -

Meet Martin Luther: an Introductory Biographical Sketch

Andrews University Seminary Studies, Spring 1984, Vol. 22, No. 1, 15-32. Copyright O 1984 by Andrews University Press. MEET MARTIN LUTHER: AN INTRODUCTORY BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH KENNETH A. STRAND Andrews University Introductory Note: The following biographical sketch is very brief, given primarily to provide the nonspecialist in Luther studies with an introductory outline of the Reformer's career. Inasmuch as the details presented are generally well-known and are readily accessible in various sources, documentation has been eliminated in this presentation. Numerous Luther biographies are available. Two of the more readable and authoritative ones in the English language which may be mentioned here are Roland H. Bainton, Here I Stand (New York: Abingdon Press, 1950), and Ernest G. Schwiebert, Luther and His Times (St. Louis, Mo.: Concordia Publishing House, 1950). These or any number of good Luther biographies may be con- sulted for a detailed treatment of Luther's career. Following the sketch below, a chronological listing is provided of important dates and events in Luther's life and in the contemporary world from the year of his birth to the year of his death. Just over 500 years ago, on November 10, 1483, Martin Luther was born in the town of Eisleben, in central Germany (now within the German Democratic Republic or "East Germany"). He was the oldest son of Hans and Margarethe (nee Ziegler) Luther, who had recently moved to Eisleben from Thuringian agricultural lands to the west. It appears that before Martin's first birthday, the family moved again-this time a few miles northward to the town of Mans- feld, which was more centrally located for the mining activity which Hans Luther had taken up. -

Helmut Schmidt Prize Lecture German Historical Institute at Washington

Helmut Schmidt Prize Lecture German Historical Institute at Washington DC December 10, 2015, 6 p.m. Austerity: Views of Chancellor Brüning’s and President Hoover’s Fiscal Policies from Across the Atlantic, 1930-32 Carl-Ludwig Holtfrerich John F. Kennedy-Institute for North American Studies Freie Universtät Berlin Contents: 0. Acknowledgements and thanks 1. Introduction 2. Fact and circumstance: similarities and differences 3. Chancellor Brüning’s fiscal policy in American public opinion 4. President Hoover’s fiscal policy as mirrored in a German newspaper 5. Conclusions 0. Acknowledgements and thanks Helmut Schmidt died exactly one month ago, on the tenth of November. As opinion polls show, he ranks as the most highly esteemed chancellor that the Federal Republic of Germany has ever had. The Helmut Schmidt Prize pays tribute to him for his part in transforming the framework of transatlantic economic cooperation. I would add that with his pragmatism and common sense he has been the most Anglo-Saxon of all chancellors in Germany’s history. I think that he would have appreciated the transatlantic perspective of my lecture today. My admiration for Helmut Schmidt has other roots as well. First, I was very impressed by the pragmatic and results-oriented instead of rules-oriented way he handled the flood in his city of Hamburg in February 1962, in his capacity as the city-state’s Senator of the police force and shortly thereafter of the interior. Second, ten years later, in the fall of 1972, I witnessed the skillful way Schmidt calmed down a group of very upset leading industrialists at a meeting of the 1 Federation of German Industry in Cologne. -

Elections in the Weimar Republic the Elections to the Constituent National

HISTORICAL EXHIBITION PRESENTED BY THE GERMAN BUNDESTAG ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ Elections in the Weimar Republic The elections to the constituent National Assembly on 19 January 1919 were the first free and democratic national elections after the fall of the monarchy. For the first time, women had the right to vote and to stand for election. The MSPD and the Centre Party, together with the German Democratic Party, which belonged to the Liberal Left, won an absolute majority of seats in the Reichstag; these three parties formed the government known as the Weimar Coalition under the chancellorship of Philipp Scheidemann of the SPD. The left-wing Socialist USPD, on the other hand, which had campaigned for sweeping collectivisation measures and radical economic changes, derived no benefit from the unrest that had persisted since the start of the November revolution and was well beaten by the MSPD and the other mainstream parties. On 6 June 1920, the first Reichstag of the Weimar democracy was elected. The governing Weimar Coalition suffered heavy losses at the polls, losing 124 seats and thus its parliamentary majority, and had to surrender the reins of government. The slightly weakened Centre Party, whose vote was down by 2.3 percentage points, the decimated German Democratic Party, whose vote slumped by 10.3 percentage points, and the rejuvenated German People’s Party (DVP) of the Liberal Right, whose share of the vote increased by 9.5 percentage points, formed a minority government under the Centrist Konstantin Fehrenbach, a government tolerated by the severely weakened MSPD, which had seen its electoral support plummet by 16.2 percentage points. -

Unternehmensgeschichte in Firmenschriften

Digitale Bibliothek Braunschweig http://www.digibib.tu-bs.de/?docid=00028932 Digitale Bibliothek Braunschweig Unternehmensgeschichte in Firmenschriften. · · Verzeichnis der Bestände der • Unlversitätsbi bl iothek Braunschweig Michael Kuhn . ; •' Hans-Joachim ZerbSt :' ·,. http://www.digibib.tu-bs.de/?docid=00028932 Digitale Bibliothek Braunschweig IiI 2688-6583 http://www.digibib.tu-bs.de/?docid=00028932 Digitale Bibliothek Braunschweig '-· Unternehmensgeschichte in Firmenschriften Verzeichnis der Bestände der Universitätsbibliothek Braunschweig Michael Kuhn Hans-Joachim Zerbst Braunschweig 1990 http://www.digibib.tu-bs.de/?docid=00028932 Digitale Bibliothek Braunschweig Veröffentlichungen der Uni ve rsitätsbibl i othek B raunschw ei g - Hrsg. von Dietmar Brandes - Heft 5 Abbildungen: Helmut Mittendorf Druck: Günter Göhmann Einband: Buchbinderei der UB c Universitätsbibliothek der Technischen Universität Braunschweig ISBN 3-927115-05-3 http://www.digibib.tu-bs.de/?docid=00028932 Digitale Bibliothek Braunschweig I n h a I t Vorwort Apotheken •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••.•••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• Banken •••••••••.••••••••••••••••••••••••..••.••••••.••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 7 Bauindustrie •••.•••••..•••••••••••••.••••••••••••••.•••••••••••••..•••••••••• 13 Bergbau ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••.•••.••••••..•••••••••.•••••••••••••.. 16 Chemische Industrie ••••••••••••..••••••.•••.••••••.•••••••••••••••••••••• 18 Eisen- und Stahlerzeugung ........................................... 27 Elektrotechnik •••••••••••••••••••••.•••.••••••.••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• -

Bernd Braun, Die Weimarer Reichskanzler. Zwölf Lebensläufe in Bildern (Photodokumente Zur Geschichte Des Parlamentarismus Und Der Politischen Parteien, Bd

Bernd Braun, Die Weimarer Reichskanzler. Zwölf Lebensläufe in Bildern (Photodokumente zur Geschichte des Parlamentarismus und der politischen Parteien, Bd. 7), Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 2011, 502 S., kart., 59,80 €. Die zwölf Politiker, die in den 14 Jahren der Weimarer Republik das Amt des Reichskanzlers bekleidet haben, sind im kollektiven Gedächtnis der Deutschen kaum mehr präsent; in der deutschen Erinne- rungskultur spielen sie – vielleicht abgesehen von Gustav Stresemann und Heinrich Brüning – so gut wie keine Rolle. Diesem Vergessen entgegenzuwirken, ist die erklärte Absicht von Bernd Braun. Der von ihm herausgegebene Bildband verdankt sich der Kooperation zwischen der „Stiftung Reichspräsi- dent-Friedrich-Ebert-Gedenkstätte“ und der „Kommission für Geschichte des Parlamentarismus und der politischen Parteien“. In deren Auftrag hat Braun in jahrelangen Recherchen in über 100 Herkunft- sorten im In- und Ausland Bildmaterial aufgespürt, darunter nicht wenige Fotos, die bisher unbekannt waren. Aus dem gesammelten Material hat er dann 800 Fotoaufnahmen ausgewählt und zu zwölf klug komponierten „Lebensläufen in Bildern“ zusammengestellt. Jedem der zwölf Reichskanzler sind 50 Seiten mit zwischen 54 und 64 Abbildungen gewidmet und jede der Bildbiografien wird durch eine drei Seiten umfassende prägnante Kurzbiografie als „Einstiegshilfe“ in den Bildteil eingeleitet. Die Quellenlage für einen Bildband über die Reichskanzler ist nach Brauns Befund äußerst mager. Das hat zwei Gründe. Zum einen lag es am damaligen technischen Stand der Fotografie: Es gab noch kein funktionierendes Teleobjektiv und man benötigte lange Belichtungszeiten, sodass manche Fotos von schlechter Qualität sind. Vor allem aber mangelte es den meisten Reichskanzlern am richtigen Gespür für Public Relations; Pressekonferenzen waren selten, von einem halben Dutzend Reichsregierungen ist kein Kabinettsfoto überliefert. -

Arthur Eloesser (1870-1938)

Andreas Terwey Arthur Eloesser (1870-1938) Kritik als Lebensform Leicht überarbeitete Fassung der im Februar 2010 an der Kulturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Europa-Universität Viadrina Frankfurt (Oder) eingereichten Arbeit zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades. Sekundärliteratur wurde nur bis zu diesem Zeitpunkt berücksichtigt. 2 Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Gangolf Hübinger, Europa-Universität Viadrina, Frankfurt (Oder) Prof. Dr. Bożena Chołuj, Europa-Universität Viadrina, Frankfurt (Oder) 3 Für Vera und Paul 4 Hiermit versichere ich, die vorliegende Arbeit selbständig verfasst zu haben. Sie wurde in keinem anderen Promotionsverfahren angenommen oder abgelehnt. Sämtliche Quellen und Hilfsmittel sind im Anhang dokumentiert. Zürich, 18.01.2016 Andreas Terwey 5 6 Inhaltsverzeichnis I. Einleitung 1. Warum Eloesser? 8 2. Fragestellungen 15 3. Quellenlage 19 II. Prenzlauer Tor: Herkunft und Schulbildung 21 III. Akademischer Werdegang 24 1. Studium 24 2. Akademische Qualifikationsschriften und das Scheitern der Habilitation 32 3. Die Schüler des germanistischen Seminars: Drei Generationen 39 4. Der Monbijouplatz als Berliner „Quartier Latin“ 44 IV. Kritik als Beruf: Eloesser und das literarische Berlin vor dem Ersten Weltkrieg 45 1. Das Amt der Theaterkritik 45 2. Literaturkritik in Zeitungen und Zeitschriften 52 2.1 Germanistische Fachzeitschriften 52 2.2 S. Fischer und die Neue Rundschau 53 2.3. Egon Fleischel und das Litterarische Echo 58 3. Geselligkeitsformen: Eine Typologie 59 3.1 Verein Berliner Presse 61 3.2 Berliner Germanistenkneipe 64 3.3 Gesellschaft für deutsche Literatur 66 3.4 Literarische Gesellschaft 67 3.5 Gesellschaft für Theatergeschichte 69 3.6 Zwanglose Gesellschaft 69 3.7 Freie Literarische Gesellschaft 71 3.8 Gesellschaft der Bibliophilen 72 3.9 Halkyonische Akademie 75 4. -

Diagnosing Nazism: US Perceptions of National Socialism, 1920-1933

DIAGNOSING NAZISM: U.S. PERCEPTIONS OF NATIONAL SOCIALISM, 1920-1933 A dissertation submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Robin L. Bowden August 2009 Dissertation written by Robin L. Bowden B.A., Kent State University, 1996 M.A., Kent State University, 1998 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2009 Approved by Mary Ann Heiss , Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Clarence E. Wunderlin, Jr. , Members, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Kenneth R. Calkins , Steven W. Hook , James A. Tyner , Accepted by Kenneth J. Bindas , Chair, Department of History John R. D. Stalvey , Dean, College of Arts and Sciences ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS………..………………………………………………iv Chapter 1. Introduction: U.S. Officials Underestimate Hitler and the Nazis……..1 2. Routine Monitoring: U.S. Officials Discover the Nazis…………......10 3. Early Dismissal: U.S. Officials Reject the Possibility of a Recovery for the Nazis…………………………………………….....57 4. Diluted Coverage: U.S. Officials Neglect the Nazis………………..106 5. Lingering Confusion: U.S. Officials Struggle to Reassess the Nazis…………………………………………………………….151 6. Forced Reevaluation: Nazi Success Leads U.S. Officials to Reconsider the Party……………………………………………......198 7. Taken by Surprise: U.S. Officials Unprepared for the Success of the Nazis……………………...……………………………….…256 8. Conclusion: Evaluating U.S. Reporting on the Nazis…………..…..309 BIBLIOGRAPHY………………………………………………………………318 iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation represents the culmination of years of work, during which the support of many has been necessary. In particular, I would like to thank two graduate school friends who stood with me every step of the way even as they finished and moved on to academic positions. -

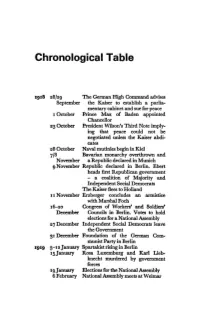

Chronological Table

Chronological Table 1918 28/29 The German High Command advises September the Kaiser to establish a parlia mentary cabinet and sue for peace 1 October Prince Max of Baden appointed Chancellor 23 October President Wilson's Third Note imply ing that peace could not be negotiated unless the Kaiser abdi cates 28 October Naval mutinies begin in Kiel 7/8 Bavarian monarchy overthrown and November a Republic declared in Munich 9 November Republic declared in Berlin. Ebert heads first Republican government - a coalition of Majority and Independent Social Democrats The Kaiser flees to Holland I I November Erzberger concludes an armistice with Marshal Foch 16-20 Congress of Workers' and Soldiers' December Councils in Berlin. Votes to hold elections for a National Assembly 27 December Independent Social Democrats leave the Government 31 December Foundation of the German Com munist Party in Berlin 1919 5-12january SpartakistrisinginBerlin 15january Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Lieb knecht murdered by government forces Igjanuary Elections for the National Assembly 6 February National Assembly meets at Weimar 174 CHRONOLOGICAL TABLE 7 April Bavarian Soviet Republic proclaimed in Munich 1May Bavarian Soviet suppressed by Reichs wehr and Bavarian Freikorps 28june Treaty of Versailles signed II August The Constitution of the German Republic formally promulgated 2I August Friedrich Ebert takes the oath as President September Hitler joins the German Workers' Party in Munich 1920 24 February Hitler announces new programme of the National Socialist German Workers Party (formally German Workers' Party) 13 March Kapp Putsch. Ebert and Ininisters flee to Stuttgart 17March Collapse of Putsch 24March Defence Minister Noske and army chief Reinhardt resign.