National Investment Plan to Reduce Deforestation and Forest Degradation (2018-2022)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mozambique Zambia South Africa Zimbabwe Tanzania

UNITED NATIONS MOZAMBIQUE Geospatial 30°E 35°E 40°E L a k UNITED REPUBLIC OF 10°S e 10°S Chinsali M a l a w TANZANIA Palma i Mocimboa da Praia R ovuma Mueda ^! Lua Mecula pu la ZAMBIA L a Quissanga k e NIASSA N Metangula y CABO DELGADO a Chiconono DEM. REP. OF s a Ancuabe Pemba THE CONGO Lichinga Montepuez Marrupa Chipata MALAWI Maúa Lilongwe Namuno Namapa a ^! gw n Mandimba Memba a io u Vila úr L L Mecubúri Nacala Kabwe Gamito Cuamba Vila Ribáué MecontaMonapo Mossuril Fingoè FurancungoCoutinho ^! Nampula 15°S Vila ^! 15°S Lago de NAMPULA TETE Junqueiro ^! Lusaka ZumboCahora Bassa Murrupula Mogincual K Nametil o afu ezi Namarrói Erego e b Mágoè Tete GiléL am i Z Moatize Milange g Angoche Lugela o Z n l a h m a bez e i ZAMBEZIA Vila n azoe Changara da Moma n M a Lake Chemba Morrumbala Maganja Bindura Guro h Kariba Pebane C Namacurra e Chinhoyi Harare Vila Quelimane u ^! Fontes iq Marondera Mopeia Marromeu b am Inhaminga Velha oz P M úngu Chinde Be ni n è SOFALA t of ManicaChimoio o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o gh ZIMBABWE o Bi Mutare Sussundenga Dondo Gweru Masvingo Beira I NDI A N Bulawayo Chibabava 20°S 20°S Espungabera Nova OCE A N Mambone Gwanda MANICA e Sav Inhassôro Vilanculos Chicualacuala Mabote Mapai INHAMBANE Lim Massinga p o p GAZA o Morrumbene Homoíne Massingir Panda ^! National capital SOUTH Inhambane Administrative capital Polokwane Guijá Inharrime Town, village o Chibuto Major airport Magude MaciaManjacazeQuissico International boundary AFRICA Administrative boundary MAPUTO Xai-Xai 25°S Nelspruit Main road 25°S Moamba Manhiça Railway Pretoria MatolaMaputo ^! ^! 0 100 200km Mbabane^!Namaacha Boane 0 50 100mi !\ Bela Johannesburg Lobamba Vista ESWATINI Map No. -

Desertification and Deforestation in Africa - R

LAND USE, LAND COVER AND SOIL SCIENCES – Vol. V – Desertification and Deforestation in Africa - R. Penny DESERTIFICATION AND DEFORESTATION IN AFRICA R. Penny Environmental and Developmental Consultant/Practitioner, Cape Town, South Africa Keywords: arid, semi-arid, dry sub-humid, drought, drylands, land degradation, land tenure, sustainability Contents 1. Introduction 2. Global Context 3. Land Degradation in Africa Today 3.1. Geographical Regions 3.2. Socio-Economic Aspects 4. Causes and Consequences 4.1. Drought and Other Disasters 4.2. Water Quality and Availability 4.3. Loss of Vegetative Cover 4.4. Loss of Soil Fertility 4.5. Poverty and Population 4.6. Effect of Land Tenure 4.7. Health 5. Combating Desertification 5.1. Past Trends 5.2. Current Attempts to Combat Desertification 5.3. Synergy of the Three Sustainable Development Conventions 5.4. The Role of Science and Technology in Combating Desertification 5.5. Synergy in Environmental Policy Development 6. Future Perspectives: The Way Forward 7. Conclusions Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch Summary UNESCO – EOLSS Africa is particularly vulnerable to desertification. Two thirds of the continent consists of desert or drylands.SAMPLE The obvious causes of desertificatiCHAPTERSon and deforestation consist of major ecosystem changes, such as land conversion for various purposes, over- dependence on natural resources and several forms of unsustainable land use. However, the issue of desertification is inseparable from social problems such as poverty and land tenure issues. Politics, war and national disasters affect the movements of people and thus impact on the land. International trade policies as well play a part in land management and/or exploitation. -

Road Impact on Deforestation and Jaguar Habitat Loss in The

ROAD IMPACT ON DEFORESTATION AND JAGUAR HABITAT LOSS IN THE MAYAN FOREST by Dalia Amor Conde Ovando University Program in Ecology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Norman L. Christensen, Supervisor ___________________________ Alexander Pfaff ___________________________ Dean L. Urban ___________________________ Randall A. Kramer Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University Program in Ecology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2008 ABSTRACT ROAD IMPACT ON DEFORESTATION AND JAGUAR HABITAT LOSS IN THE MAYAN FOREST by Dalia Amor Conde Ovando University Program in Ecology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Norman L. Christensen, Supervisor ___________________________ Alexander Pfaff ___________________________ Dean L. Urban ___________________________ Randall A. Kramer An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University Program in Ecology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2008 Copyright by Dalia Amor Conde Ovando 2008 Abstract The construction of roads, either as an economic tool or as necessity for the implementation of other infrastructure projects is increasing in the tropical forest worldwide. However, roads are one of the main deforestation drivers in the tropics. In this study we analyzed the impact of road investments on both deforestation and jaguar habitat loss, in the Mayan Forest. As well we used these results to forecast the impact of two road investments planned in the region. Our results show that roads are the single deforestation driver in low developed areas, whether many other drivers play and important role in high developed areas. In the short term, the impact of a road in a low developed area is lower than in a road in a high developed area, which could be the result of the lag effect between road construction and forest colonization. -

Hidden Deforestation in the Brazil - China Beef and Leather Trade 1

Hidden deforestation in the Brazil - China beef and leather trade 1 Hidden deforestation in the Brazil - China beef and leather trade Christina MacFarquhar, Alex Morrice, Andre Vasconcelos August 2019 Key points: China is Brazil’s biggest export market for cattle products, • Cattle ranching is the leading direct driver of deforestation which are a major driver of deforestation and other native and other native vegetation clearance in Brazil, and some vegetation loss in Brazil. This brief identifies 43 companies international beef and leather supply chains are linked to worldwide that are highly exposed to deforestation risk through these impacts. the Brazil-China beef and leather trade, and which have significant potential to help reduce this risk. The brief shows • China (including Hong Kong) is Brazil’s biggest importer of which of these companies have published policies to address beef and leather, and many companies linked to this trade are deforestation risk related to these commodities. It also reveals exposed to deforestation risk. the supplier-buyer relationships between these companies, • We identify 43 companies globally that are particularly exposed and how their connections may mean even those buyers with to the deforestation risk associated with the Brazil-China beef commitments to reduce or end deforestation may not be able to and leather trade and have the potential to reduce these risks. meet them. It then makes recommendations for the next steps companies can take to address deforestation risk. • Most of these companies have not yet published sustainable sourcing policies to address this risk. The companies include cattle processors operating in Brazil, processors and manufacturers operating in China, and • Most appear unable to guarantee that their supply chains are manufacturers and retailers headquartered in Europe and the deforestation-free, because they, or a supplier, lack a strong United States of America (US). -

Introduction - the Trident Project

Introduction - The Trident Project January 2014 www.first-quantum.com TSX: FM LSE: FQM LuSE: FQMZ TRIDENT PROJECT LOCATION January 2014 2 ABOUT THE TRIDENT PROJECT Trident Project: . Located in the Solwezi District of Northwestern Province, Zambia . Approximately 150km from Solwezi on the T5 main road to Mwinilunga . Comprises five prospecting large scale licences . A number of attractive base metal prospects including the Sentinel deposit and the Enterprise deposit . 5 x large-scale mining licences awarded 20 April 2011 for 25 years tenure . Land use agreement signed 14 July 2011 . EIA approved 8 July 2011 and Addendum 12 August 2013 . Resettlement Action Plan approved 15 October 2013 January 2014 3 TRIDENT PROJECT LAYOUT January 2014 4 SENTINEL MINE IN CONSTRUCTION – COMMISSIONING MID 2014 Updated resource published May 2012: . 514 boreholes for 172,692m defined an NI43-101 resource of: . Total measured & indicated : 1,027Mt @ 0.51% Cu . Inferred : 165Mt @ 0.42% Cu . Cut-off : 0.2% Cu . Mineral Reserve: 774 Mt @ 0.50% Cu . Proved : 476 Mt @ 0.52% Cu . Probable : 298 Mt @ 0.47%Cu. Strip ratio 2.2 : 1 Mine planning: . Grade of 0.5% Cu requires a high throughput of 55 Mtpa to achieve production target of 280 – 300,000t Cu per annum. Sentinel will put Zambia at the forefront of global mining technology January 2014 5 ENTERPRISE MINE IN APPROVAL – EARLY WORKS UNDERWAY Maiden resource published December 2012: . 359 boreholes for 116,000m defined an NI43-101 resource of: . Total measured indicated : 40.1Mt @ 1.07% Ni . Inferred : 7.1Mt @ 0.70% Ni . Cutoff : 0.15% Ni . -

Desertification and Agriculture

BRIEFING Desertification and agriculture SUMMARY Desertification is a land degradation process that occurs in drylands. It affects the land's capacity to supply ecosystem services, such as producing food or hosting biodiversity, to mention the most well-known ones. Its drivers are related to both human activity and the climate, and depend on the specific context. More than 1 billion people in some 100 countries face some level of risk related to the effects of desertification. Climate change can further increase the risk of desertification for those regions of the world that may change into drylands for climatic reasons. Desertification is reversible, but that requires proper indicators to send out alerts about the potential risk of desertification while there is still time and scope for remedial action. However, issues related to the availability and comparability of data across various regions of the world pose big challenges when it comes to measuring and monitoring desertification processes. The United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification and the UN sustainable development goals provide a global framework for assessing desertification. The 2018 World Atlas of Desertification introduced the concept of 'convergence of evidence' to identify areas where multiple pressures cause land change processes relevant to land degradation, of which desertification is a striking example. Desertification involves many environmental and socio-economic aspects. It has many causes and triggers many consequences. A major cause is unsustainable agriculture, a major consequence is the threat to food production. To fully comprehend this two-way relationship requires to understand how agriculture affects land quality, what risks land degradation poses for agricultural production and to what extent a change in agricultural practices can reverse the trend. -

Human Population Growth and Its Implications on the Use and Trends of Land Resources in Migori County, Kenya

HUMAN POPULATION GROWTH AND ITS IMPLICATIONS ON THE USE AND TRENDS OF LAND RESOURCES IN MIGORI COUNTY, KENYA PAULINE TOLO OGOLA A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Award of the Degree of Master of Environmental Studies (Agroforestry and Rural Development) in the School of Environmental Studies of Kenyatta University NOVEMBR, 2018 1 DEDICATION To my loving parents, Mr. and Mrs. Ogola, With long life He will satisfy you i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First of all, I am grateful to the Man above who gave me strength and health throughout this study. For sure, His goodness and Mercies are new every day. Secondly, I am greatly indebted to my supervisors Dr. Letema and Dr. Obade for their wise counsel and patience. Thirdly, I would like to convey my utmost gratitude to my parents and siblings for their moral support and prayers. Special thanks to my brother Stephen Ogeda for supporting me financially. Finally, I wish to express many thanks to my colleagues at the Regional Centre for Mapping of Resources for Development and friends who have offered their support in kind and deed. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS DECLARATION………………………………………………………………………… Error! Bookmark not defined. DEDICATION…………………………………………………………………………...i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT……………………………………………………………...ii LIST OF TABLES……………………………………………………………………...vi LIST OF FIGURES……………………………………………………………………vii ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS……………………………………………….viii ABSTRACT………………………………………………………………………………i x CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………..1 1.1 Background to the Problem ......................................................................................... -

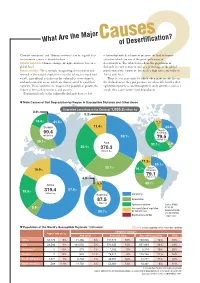

What Are the Major Causes of Desertification?

What Are the Major Causesof Desertification? ‘Climatic variations’ and ‘Human activities’ can be regarded as relationship with development pressure on land by human the two main causes of desertification. activities which are one of the principal causes of Climatic variations: Climate change, drought, moisture loss on a desertification. The table below shows the population in global level drylands by each continent and as a percentage of the global Human activities: These include overgrazing, deforestation and population of the continent. It reveals a high ratio especially in removal of the natural vegetation cover(by taking too much fuel Africa and Asia. wood), agricultural activities in the vulnerable ecosystems of There is a vicious circle by which when many people live in arid and semi-arid areas, which are thus strained beyond their the dryland areas, they put pressure on vulnerable land by their capacity. These activities are triggered by population growth, the agricultural practices and through their daily activities, and as a impact of the market economy, and poverty. result, they cause further land degradation. Population levels of the vulnerable drylands have a close 2 ▼ Main Causes of Soil Degradation by Region in Susceptible Drylands and Other Areas Degraded Land Area in the Dryland: 1,035.2 million ha 0.9% 0.3% 18.4% 41.5% 7.7 % Europe 11.4% 34.8% North 99.4 America million ha 32.1% 79.5 million ha 39.1% Asia 52.1% 5.4 26.1% 370.3 % million ha 11.5% 33.1% 30.1% South 16.9% 14.7% America 79.1 million ha 4.8% 5.5 40.7% Africa -

World Bank Document

INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT DEVELOPMENT ECONOMICS DEPARTMENT Public Disclosure Authorized URBAN AND REGIONAL ECONOMICS DIVISION URBAN AND REGIONAL PAPER NO.74-1 Public Disclosure Authorized THE DEVELOPMENT OF REGIONAL CENTERS - ZAMBIA JOHN C. ENGLISH February 1974 Public Disclosure Authorized This paper is prepared as Annex II to the Urban Sector Survey Report - Repul-lic of Zambia Report No.490-ZA Confidential Public Disclosure Authorized Table of Contents THE DEVELOPMENT OF REGIONAL CENTERS A. Regional Growth and Urban Development 1. Introduction 2. Structure of the Economy 3. Spatial Consequences 4. Public Investment in First and Second Plans 5. Decentralization of Manufacturing 6. Potential Impact on Distribution of Urban Growth B. Chipata and Eastern Province 1. Existing Characteristics of Chipata 2. Developments in Eastern Province 3. Future Growth in Chipata 4. Other Urban Centers in the Province Table 1 - Gross Domestic Product by Kind of Economic Activity at Current Purchasers Values (K million) 2 - Percentage Distribution of Sales by Sections of Purchase - 1969 3 - Distribution of Imports by Origin, Grouped Sectors - 1969 4 - Zambia - Distribution of Imported Inputs by Sector - 1969 5 - Employment by Province and Sector, 1968 6 - Distribution of Manufacturing Establishments among Provinces by Manufacturing Activity 1969 7 - Average Agricultural Crop Production by Province 1969-72 8 - Zambia - Proportion of Population Aged 10-14 Enrolled in Primary School by Province 1972 9 - Zambia. Distribution of -

EML Contracts Profile 2017.Cdr

50 ANNIVERSARY 1965 - 2015 www.eml-eis.com VALUE SERVICE QUALITY LOYALTY PRICE Contracting Reliable Quality Service since 1968 in the field of Electrical Contracting SUPPORT Zambia. COMPANY 2017-8 PROFILE 1 company details Name of the Company: Electrical Maintenance Lusaka Ltd. Address: Head Office Plot 195 Luanshya Road, East End Off Great North End Lusaka, 10101 Zambia Contact Details: +260 211 227824 +260 237014 - FAX [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] website: www.eml-eis.com 50 ANNIVERSARY 1965 - 2015 Contracts Department history 2 HISTORY: FOUNDER AND OWNER Mr George Narder achieved electrical and mechanical engineering qualifications in Italy following which he worked in Switzerland for 6 years. In 1963 he arrived in Zambia as part of a testing and commissioning team for the newly built Kariba Power Station and has lived in Zambia ever since. Mr Narder started an electrical engineering business in 1965, registered as Electrical Maintenance Lusaka LTD (EML). He has managed and run the company as its CEO for more than 50 years. Under his direct entrepreneurial management, EML has grown into one of the largest and most respected electrical and electronic engineering companies in Zambia. The company benefits from more than 60 years of his passion, knowledge and expertise. EML is proud to have participated in many facets of the social and Mr George Narder, Comm economic development of the country ELECTRICAL MAINTENANCE LUSAKA (EML) MOTO “Always with our customers” To continue improving on our 50 years of reliable quality service to the Zambian industry. our vision our mission e strive to remain one of Zambia’s ur added value is to provide quality leading and most diverse electrical products, service and training for all cWontracting, manufacturing, retail and electricalO requirements across the country, training companies. -

Zambia USADF Country Portfolio

Zambia USADF Country Portfolio Overview: Country program established in 1984 and reopened in U.S. African Development Foundation Partner Organization: Keepers Zambia 2004. USADF currently manages a portfolio of 23 projects and one Country Program Coordinator: Guy Kahokola Foundation (KZF) Cooperative Agreement. Total active commitment is $2.9 million. Suite 103 Foxdale Court Office Park Program Manager: Victor Makasa Agricultural investments total $2.6 million. Youth-led enterprise 609 Zambezi Road, Roma Tel: +260 211 293333 investments total $20,000. Lusaka, Zambia Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Country Strategy: The program focuses on support to agricultural enterprises, including organic farming as Zambia has been identified as a Feed the Future country. In addition, there are investments in off-grid energy and youth led-enterprises. Enterprise Duration Grant Size Description Mongu Dairy Cooperative Society 2012-2017 $152,381 Sector: Agriculture (Dairy) Limited Town/City: Mongu District in the Western Province 2705-ZMB Summary: The project funds will be used to increase the production and sales of milk through the purchase of improved breed cows, transportation, and storage equipment. Chibusa Home Based Care 2013-2018 $187,789 Sector: Agriculture (Food Processing) Association Town/City: Mungwi District in the Northern Province of Zambia 2925-ZMB Summary: The project funds will be used to provide working capital for purchasing grains, increase milling capacity, build a storage warehouse, and provide funds to improve marketing. Ushaa Area Farmers Association 2013-2018 $94,960 Sector: Agriculture (Rice) Limited Town/City: Mongu District in the Western Province of Zambia 2937-ZMB Summary: The project funds will be used to provide working capital for purchasing rice, build a storage warehouse, and provide funds to improve marketing. -

Value Chain Analysis Tourism Zambia

Value Chain Analysis Tourism Zambia Commissioned by The Centre for the Promotion of Imports from developing countries (CBI) Acorn Tourism Consulting Ltd November 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS MANAGEMENT SUMMARY 1. INTRODUCTION 2. EU TOURISM MARKETS AND ZAMBIA’S COMPETITIVE POSITION 2.1 Export Market Demand and Trends 2.2 Zambia’s Competitiveness 2.3 Strategic Context: Plans for the Zambian Tourism Sector 2.4 Potential for New Products and Regions 3. ZAMBIA’S TOURISM VALUE CHAIN 3.1 Structure and Governance of the Value Chain 3.2 Governance Challenges 3.3 Sustainability of the Tourism Value Chain 4. OPPORTUNITIES AND OBSTACLES 4.1 Key Opportunities for Zambian SMEs 4.2 Obstacles for Zambian SMEs 4.3 Public Sector Opportunities and Constraints 5. WHAT CBI CAN DO TO SUPPORT A MORE COMPETITIVE AND SUSTAINABLE TOURISM VALUE CHAIN IN ZAMBIA 2 ACCRONYMS CSR Corporate Social Responsibility DNPW Department of National Parks and Wildlife EU European Union GMA Game Management Area KAZA Kavango Zambezi KKIA Kenneth Kwanda International Airport LTA Livingstone Tourist Association NP National Park MoTA Ministry of Tourism and Arts MOU Memorandum of Understanding NHCC National Heritage Conservation Commission PMU Project Management Unit PUM PUM Netherlands Senior Experts RETOSA Regional Tourism Organisation of Southern Africa SADC South African Development Community SEO Search Engine Optimisation SME Small and Medium sized Enterprises TAP Technical Assistance Programme TCZ Tourism Council of Zambia TDA Tourism Development Area TEVETA Technical Education, Vocational and Entrepreneurship Training Authority UNWTO United Nations World Tourism Organisation ZATEX Zambia Tourism Exposition ZATO Zambia Association of Tour Operators ZITHS Zambia Institute for Tourism and Hospitality Studies ZMK Zambia kwacha ZTA Zambia Tourism Agency ZTMP Zambia Tourism Master Plan 3 MANAGEMENT SUMMARY Zambia’s appeal to the European leisure visitor is based on its natural resources, including its unspoiled and varied landscape.