City Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

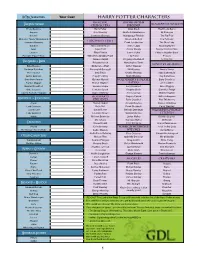

Harry Potter Characters

Lo T R C h a r a c t e r s Your Cast Harry Potter Characters Principal Order of the Hogwarts Denizens The Fellowship Characters Phoenix Frodo Baggins Harry Potter Sirius Black The Bloody Baron Aragorn Ron Weasley Aberforth Dumbledore Sir Cadogan Boromir Hermione Granger Mundungus Fletcher The Fat Friar Meriadoc "Merry" Brandybuck Alice Longbottom The Fat Lady Hogwarts Staff Samwise Gamgee Frank Longbottom The Grey Lady Gandalf Albus Dumbledore Remus Lupin Moaning Myrtle Gimli Argus Filch Alastor Moody Nearly Headless Nick Legolas Filius Flitwick James Potter Phineas Nigellus Black Peregrin "Pippin" Took Wilhelmina Grubbly-Plank Lily Potter Peeves Rubeus Hagrid Kingsley Shacklebolt Sorting Hat The Shire & Bree Rolanda Hooch Nymphadora Tonks Ministry of Magic Bilbo Baggins Gilderoy Lockhart Arthur Weasley Barliman Butterbur Minerva McGonagall Bill Weasley Amelia Bones Rosie Cotton Irma Pince Charlie Weasley Mary Cattermole Gaffer Gamgee Poppy Pomfrey Molly Weasley Reg Cattermole Bree Gate Keeper Quirinus Quirrell Voldemort & Death Barty Crouch Sr Farmer Maggot Horace Slughorn Eaters John Dawlish Everard Proudfoot Severus Snape Lord Voldemort Amos Diggory Otho Sackville Pomona Sprout Regulus Black Cornelius Fudge Lobelia Sackville-Baggins Sybill Trelawney Alecto Carrow Mafalda Hopkirk Hogwarts Amycus Carrow Rufus Scrimgeour Rivendell & Lothlórien Students Barty Crouch Jr Pius Thicknesse Arwen Hannah Abbott Antonin Dolohov Dolores Umbridge Lord Celeborn Katie Bell Fenrir Greyback Percy Weasley Lord Elrond Susan Bones Bellatrix Lestrange Wizarding World Lady Galadriel Lavender Brown Walden Macnair Citizens Haldir Millicent Bulstrode Lucius Malfoy Bathilda Bagshot Cho Chang Narcissa Malfoy Mr Borgin Creatures Vincent Crabb Peter Pettigrew Ariana Dumbledore Shelob Colin Creevey Foreign wizards & Food Trolley Lady The Balrog - Durin's Bane Cedric Diggory witches Auntie Muriel Justin Finch-Fletchley Fleur Delacour Xenophilius Lovegood Other Characters Marcus Flint Gabrielle Delacour Mr. -

Erps Reveal Retrieval of Domain and Specific Knowledge During

Harry Potter and the language-knowledge interface: ERPs reveal retrieval of domain and specific knowledge during reading Melissa Troyer and Marta Kutas (UCSD) [email protected] Across cognitive systems, world knowledge allows individuals to organize raw sensation into meaningful experiences. Language processing is no exception—words cue world knowledge which can be rapidly brought to mind in real time. It stands to reason that how much and how well individuals know things will impact what each individual brings to mind during real-time comprehension; yet to date, models of real-time language processing have not taken this variability into account. We addressed this issue by studying a linguistically rich, yet constrained, popular domain—the fictional world of Harry Potter (HP), by J.K. Rowling. In a series of three studies (Experiment 1 reported in [1]), we recorded event-related brain potentials (ERPs) while young adults who varied in their knowledge of HP read sentences about HP “facts” and/or sentences describing general topics (Table 1). As a measure of real-time knowledge retrieval, we focused on N400 amplitude, a brain potential with a centro-parietal maximum occurring ~250-500 ms post stimulus onset that is sensitive to factors impacting the ease of retrieval from semantic memory, with larger reductions in N400 (i.e., more positive-going N400 potentials) associated with greater ease of retrieval [2]. Across all three studies, we found that individuals’ domain knowledge of HP (assessed via an offline multiple-choice trivia quiz; details in [1]) was moderately-to-strongly correlated with average N400 brain potentials to contextually supported (i.e., accurate) words completing sentences about HP, but not to unsupported (inaccurate) endings, nor to N400 effects (i.e., difference ERPs) of more vs. -

6 Harry Potter Fanfiction

Univerzita Hradec Králové Pedagogická fakulta Katedra anglického jazyka a literatury Vývoj vedlejších postav ságy Harryho Pottera ve fanfiction Development of Minor Characters from Harry Potter Saga in Fanfiction Diplomová práce Autor: Bc. Anna Fólová Studijní program: N7504 Učitelství pro střední školy Studijní obor: Učitelství pro střední školy – hudební výchova, Učitelství pro 2. stupeň ZŠ – anglický jazyk a literatura Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Jan Suk, Ph.D. Hradec Králové 2019 Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto bakalářskou práci vypracovala samostatně a uvedla jsem všechny použité prameny a literaturu. V Hradci Králové dne 1.4.2019 Anotace FÓLOVÁ, Anna. Vývoj vedlejších postav ságy Harryho Pottera ve fanfiction. Hradec Králové: Pedagogická fakulta Univerzity Hradec Králové, 2019. 63 s. Diplomová práce. Tato práce představuje fanfikci a fanouškovskou tvorbu obecně. Uvádí její historický vývoj, reakce spisovatelů děl, podle kterých fanfikce vzniká a problémy s legální stránkou fanfikce. Popisuje fandom Harryho Pottera a jeho specifika, fandom také porovnává s fandomy ostatních děl převážně fantasy a science-fiction literatury. V praktické části potom analyzuje dvojici vybraných postav a jejich vývoj, které popisuje nejprve z pohledu původního díla, poté z pohledu fanfikce a posléze vývoj porovnává a shrnuje. Klíčová slova: Harry Potter, Fanfiction, Fandom, Vedlejší postavy. Annotation FÓLOVÁ, Anna. Development of Minor Characters from Harry Potter Saga in Fanfiction. Hradec Králové: Pedagogical Faculty, University of Hradec Králové, 2019, 63 pp. Diploma dissertation. This thesis presents fanfiction and fanwork in general. It introduces its historical development, reaction of the original work authors´ and legal issues of fanfiction. This thesis describes fandom of Harry Potter and its particularities, compares it with other fandoms, mostly fantasy and science fiction works. -

“Harry – Yer a Wizard” Exploring J

Wissenschaftliche Beiträge aus dem Tectum Verlag Reihe Anglistik Wissenschaftliche Beiträge aus dem Tectum Verlag Reihe Anglistik Band 6 Marion Gymnich | Hanne Birk | Denise Burkhard (Eds.) “Harry – yer a wizard” Exploring J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter Universe Tectum Verlag Marion Gymnich, Hanne Birk and Denise Burkhard (Eds.) “Harry – yer a wizard” Exploring J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter Universe Wissenschaftliche Beiträge aus demT ectum Verlag, Reihe: Anglistik; Bd. 6 © Tectum Verlag – ein Verlag in der Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden 2017 ISBN: 978-3-8288-6751-2 (Dieser Titel ist zugleich als gedrucktes Werk unter der ISBN 978-3-8288-4035-5 und als ePub unter der ISBN 978-3-8288-6752-9 im Tectum Verlag erschienen.) ISSN: 1861-6859 Umschlaggestaltung: Tectum Verlag, unter Verwendung zweier Fotografien von Schleiereule Merlin und Janna Weinsch, aufgenommen in der Falknerei Pierre Schmidt (Erftstadt/Gymnicher Mühle) | © Denise Burkhard Informationen zum Verlagsprogramm finden Sie unter www.tectum-verlag.de Bibliografische Informationen der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Angaben sind im Internet über http://dnb.ddb.de abrufbar. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available online at http://dnb.ddb.de. Contents Hanne Birk, Denise Burkhard and Marion Gymnich ‘Happy Birthday, Harry!’: Celebrating the Success of the Harry Potter Phenomenon ........ 7 Marion Gymnich and Klaus Scheunemann The ‘Harry Potter Phenomenon’: Forms of World Building in the Novels, the Translations, the Film Series and the Fandom ................................................................. 11 Part I: The Harry Potter Series and its Sources Laura Hartmann The Black Dog and the Boggart: Fantastic Beasts in Joanne K. -

Professor Dumbledore's Advice for Law Deans, 39 U

UIC School of Law UIC Law Open Access Repository UIC Law Open Access Faculty Scholarship 2008 Professor Dumbledore's Advice for Law Deans, 39 U. Tol. L. Rev. 269 (2008) Darby Dickerson John Marshall Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.uic.edu/facpubs Part of the Legal Education Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Recommended Citation Darby Dickerson, Professor Dumbledore's Advice for Law Deans, 39 U. Tol. L. Rev. 269 (2008) https://repository.law.uic.edu/facpubs/640 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UIC Law Open Access Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UIC Law Open Access Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of UIC Law Open Access Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PROFESSOR DUMBLEDORE'S ADVICE FOR LAW DEANS Darby Dickerson* INTRODUCTION LBUS Percival Wulfric Brian Dumbledore.' Adorned with a long silver beard, midnight blue robes, and half-moon glasses,2 Dumbledore * Vice President and Dean, Stetson University College of Law. I would like to thank my research assistant, Casey Stoutamire, for her work on this piece, and my colleague, Professor Brooke Bowman, for her editing assistance. Also, as the author of the ALWD Citation Manual, I want to thank the University of Toledo Law Review editors for keeping my citations in that format and for allowing me to dispense with some traditional citation niceties, such as the "supra n. _, at " construction for books in the Harry Potter series and the strict use of id., so that readers can more easily locate the sources cited. -

Harry's Character Influenced by His Parent's Death

Roaa Alwandi En2303 Autumn 2012 School of Education and Environment Kristianstad University Supervisor: Jane Mattisson From “Abnormal” Orphan to Celebrated Hero: A discussion of Harry’s development in J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone He’ll be famous – a legend – I wouldn’t be surprised if today was known as Harry Potter Day in the future – there will be books written about Harry – every child in our world will know his name! (Rowling 20) When these words were written fifteen years ago the author had no idea how true they would become. Now, in 2012, the Harry Potter series is well-known almost worldwide. The books took the world by storm, created a whole world of its own and were, and indeed are still, read by thousands of people around the globe. As the books have turned into a phenomenon, this essay will explore the character of one of our most beloved fictional characters, Harry Potter himself. The purpose of this essay is to investigate Harry’s character in J.K. Rowling’s first novel and to show that it is his character that is one of the chief reasons for the enormous popularity of the book, and indeed, of the entire series. The various differences in Harry’s role are well-illustrated by close reading of significant passages in different parts of the novel. Harry is different from other people because he belongs to two worlds; he is however, a native of neither. He does not belong in the muggle world because he has magical powers, he is an orphan who is loved by no one, and is frequently bullied. -

Critical Literacy in a Global Context: Reading Harry Potter

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Online @ ECU Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses: Doctorates and Masters Theses 2006 Critical literacy in a global context: Reading Harry Potter Jill Reading Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Reading, J. (2006). Critical literacy in a global context: Reading Harry Potter. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/ 47 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/47 Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses: Doctorates and Masters Theses 2006 Critical literacy in a global context: reading Harry Potter Jill Reading Edith Cowan University Recommended Citation Reading, J. (2006). Critical literacy in a global context: reading Harry Potter. Retrieved from http://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/47 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. http://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/47 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). -

Myth and the Modern World View in Jk

BENEATH THE INVISIBILITY CLOAK: MYTH AND THE MODERN WORLD VIEW IN J.K. ROWLING’S HARRY POTTER A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Humanities By MARY ELIZABETH NOREN B.A., Antioch University McGregor, 2004 2007 Wright State University COPYRIGHT BY MARY ELIZABETH NOREN 2007 WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES July 23, 2007 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Mary Elizabeth Noren ENTITLED Beneath The Invisibility Cloak: Myth And The Modern World View In J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Humanities. ______________________________ Carol Nathanson, Ph.D. Thesis Project Director ______________________________ Ava Chamberlain, Ph.D. Director, Master of Humanities Program Committee on Final Examination: ___________________________________ Carol Nathanson, Ph.D. Thesis Project Co-Director ___________________________________ Jeannette Marchand, Ph.D. Thesis Project Co-Director ___________________________________ Bruce LaForse, Ph.D. Committee Member __________________________________ Joseph F. Thomas, Ph.D. Dean, School of Graduate Studies ABSTRACT Noren, Mary Elizabeth. M.A., Department of Humanities, Wright State University, 2006. Beneath The Invisibility Cloak: Myth And The Modern World View In J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter. J.K. Rowling, best selling author of the Harry Potter series, uses mythology to add layers of meaning to her own creative storylines, to provide insight into the characters and plot, and to subtly foreshadow events to come. Rowling reinvents the old myths referred to in her text by creating surprise twists that are a reversal of the reader’s expectations. Ultimately, Rowling’s reworking of established mythology reveals the author’s own modern perspective about what makes a hero, the power of choice, and the nature of evil. -

MATERNAL ATTACHMENT in JK ROWLING's HARRY POTTER

i THE MAGIC OF A MOTHER’S LOVE: MATERNAL ATTACHMENT IN J.K. ROWLING’s HARRY POTTER SERIES A thesis submitted to the Kent State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for University Honors By Adrienne Savoldi, December 2013 i ii Thesis written by Adrienne Savoldi Approved by ______________________________________________________, Advisor _____________________________________, Chair, Department of English Accepted by __________________________________________, Dean, Honors College ii iii Table of Contents Foreword…………………………………………………………………………….…1 Introduction………………………………………………………………………..…...3 Chapter One…………………………………………………………………………….9 Applying Mother Theory to Harry Potter Chapter Two……………………………………………………………………………23 Psychoanalysis in Harry Potter: A Literature Review Chapter Three…………………………………………………………………………..31 The Lost Boys: Harry Potter, Lord Voldemort, and Parental Affection Chapter Four……………………………………………………………………….......60 The Boy Who Wasn’t Chosen: Neville Longbottom and His Present, Yet Absent, Parents Chapter Five………………………………………………………………………...…73 Man Behind the Monster: Hagrid and Motherless Magical Creatures Conclusion……………………………………………………………………...……...84 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………...…87 iii iv Acknowledgments This project was greater than anything I ever attempted before, and I could not do it without a number of individuals. First, a special thank-you to Dr. Vera Camden, my advisor, for all her help and guidance with this project, as well as for giving me the opportunity to be her research assistant, all of which helped me realize my desire and passion to become a librarian. I would also like to thank my defense committee: Dr. Susan Sainato for her phenomenal Children’s Literature class in spring 2011, Dr. James Bracken for employing me and for showing me all those beautiful rare books, and Dr. Elizabeth Howard for her excellent suggestions regarding this paper. Additional thank- yous to the wonderful people in the English Department and Honors College, especially Dr. -

“Magic Is Might” Reading the Harry Potter Heptalogy Through a Dystopian Lens

“Magic Is Might” Reading the Harry Potter Heptalogy through a Dystopian Lens provided by Trepo - Institutional Repository of Tampere University View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk CORE brought to you by Kaisa Pyysalo University of Tampere Faculty of Communication Sciences Master’s Programme in English Language and Literature Pro Gradu Thesis April 2017 Tampereen yliopisto Englannin kielen ja kirjallisuuden maisteriopinnot Viestintätieteiden tiedekunta PYYSALO, KAISA: “Magic Is Might.” Reading the Harry Potter Heptalogy through a Dystopian Lens Pro gradu -tutkielma, 119 sivua + lähdeluettelo 4 sivua Huhtikuu 2017 Tarkastelen pro gradu -tutkielmassani J. K. Rowlingin maailmanlaatuista suosiota saavuttanutta Harry Potter -kirjasarjaa (1997–2007) dystopian näkökulmasta. Romaaneja analysoimalla tutkin, esiintyykö usein synkkänä ja toivottomana koetun dystopiakirjallisuuden ominaispiirteitä myös teoksissa, jotka tavallisesti luokitellaan viattomaksi lastenkirjallisuudeksi. Tutkielman tarkoituksena on selvittää, mitä hyötyä nuorille ja vanhemmillekin lukijoille on dystopiaan tutustumisesta ja mitä he voivat tästä kirjallisuudenlajista oppia. Vaikka monia kirjallisia teoksia kuvataan dystooppisiksi, ei tälle fiktion tyylisuunnalle löydy aiemmasta tutkimuksesta selkeää määritelmää, joka pätisi kaikkiin dystopioiksi kutsuttuihin teoksiin. Tutkielmassani luon dystopiakirjallisuudelle oman määritelmäni, joka perustuu sekä alan aiempaan tutkimukseen että omaan tulkintaani kolmesta romaanista, jotka usein luetaan kuuluviksi dystopian -

Myth and the Modern World View in JK Rowling's Harry Potter

Wright State University CORE Scholar Browse all Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2007 Beneath The Invisibility Cloak: Myth and The Modern World View in J.K. Rowling's Harry Potter Mary Elizabeth Noren Wright State University Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Repository Citation Noren, Mary Elizabeth, "Beneath The Invisibility Cloak: Myth and The Modern World View in J.K. Rowling's Harry Potter" (2007). Browse all Theses and Dissertations. 166. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all/166 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Browse all Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BENEATH THE INVISIBILITY CLOAK: MYTH AND THE MODERN WORLD VIEW IN J.K. ROWLING’S HARRY POTTER A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Humanities By MARY ELIZABETH NOREN B.A., Antioch University McGregor, 2004 2007 Wright State University COPYRIGHT BY MARY ELIZABETH NOREN 2007 WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES July 23, 2007 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Mary Elizabeth Noren ENTITLED Beneath The Invisibility Cloak: Myth And The Modern World View In J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Humanities. ______________________________ Carol Nathanson, Ph.D. Thesis Project Director ______________________________ Ava Chamberlain, Ph.D. -

Harry Potter the Complete Guide

Harry Potter The Complete Guide PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Fri, 12 Aug 2011 00:11:51 UTC Contents Articles Overview 1 Universe 1 Places 14 Factions and characters 31 Characters 31 Supporting characters 57 Harry Potter 76 Ron Weasley 87 Hermione Granger 95 Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry 104 Albus Dumbledore 121 Rubeus Hagrid 133 Severus Snape 142 Hogwarts staff 153 Draco Malfoy 167 Lord Voldemort 175 Ministry of Magic 187 Order of the Phoenix 202 Dumbledore's Army 220 Magic 235 Magic 235 Spells 251 Magical creatures 282 Magical objects 299 Muggle 328 Quidditch 330 Books 343 Harry Potter book series 343 Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone 364 Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets 379 Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban 387 Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire 392 Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix 399 Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince 406 Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows 415 Other books 430 Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them 430 Quidditch Through the Ages 434 The Tales of Beedle the Bard 436 Harry Potter prequel 442 Films 444 Harry Potter film series 444 Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone 461 Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets 477 Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban 483 Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire 492 Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix 499 Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince 516 Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 1 534 Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows –