Critical Literacy in a Global Context: Reading Harry Potter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New England Reading Association

Volume 46 • Number 1 • 2010 New England Reading Association Mural in response to children’s and young adolescent literature N news E education R research A article The New England Reading JOURNAL Association Journal Volume 46 • Number 1 • 2010 EXECUTIVE BOARD DELEGATES Editor: Helen R. Abadiano PRESIDENT CONNECTICUT NEW HAMPSHIRE Judith Schoenfeld James Johnston Jennifer McMahon Associate Editors: Jesse P. Turner Rhode Island College Central CT State University The New Hampton School Lynda M. Valerie Providence, RI New Britain, CT New Hampton, NH Department Editors PRESIDENT-ELECT Linda Kauffmann Margaret Salt Spring Hermann Eileen B. Leavitt Capitol Region Education Council Plymouth Elementary School Julia Kara-Soteriou Institute on Disability/UCED Hartford, CT Plymouth, NH Diane Kern Durham, NH Sandip LeeAnne Wilson Miriam Klein Gerard Buteau 1st VICE PRESIDENT Sage Park Middle School Plymouth State University Editorial Board Kathleen Itterly Windsor, CT Plymouth, NH Margaret Salt, Chair Westfield State College Kathleen Desrosiers Westfield, MA MAINE RHODE ISLAND Miriam Klein Linda Crumrine Courtney Hughes Barbara Lovley 2nd VICE PRESIDENT Plummer Motz School Coventry Public Schools Nancy Witherell Lindy Johnson Falmouth, ME Coventry, RI Literacy Coordinator Journal Review Board East Montpelier, VT Barbara Lovley Kathleen Desrosiers Julie Coiro Fort Kent Elementary School Warwick Public Schools Ellen Fingeret PAST PRESIDENT Fort Kent, ME Warwick, RI Carol Reppucci Catherine Kurkjian Margaret Salt Central CT State University Jane Wellman-Little Lizabeth Widdifield Janet Trembly New Britain, CT University of Maine Coventry Public Schools Kenneth J. Weiss Orono, ME Coventry, RI Nancy Witherell SECRETARY _________________________ Subscription rate for Association members Angela Yakovleff MASSACHUSETTS VERMONT and institutions is $35.00 per year; Whitingham Elementary School Cynthia Rizzo Janet Poeton Retired educator membership is $20.00 Wilmington, VT Wheelock College Retired Classroom Teacher per year; Single issues are $20.00 each. -

Critical Literacy, Digital Platforms, and Datafication

Critical Literacy, Digital Platforms, and Datafication T. Philip Nichols, Baylor University Anna Smith, Illinois State University Scott Bulfin, Monash University Amy Stornaiuolo, University of Pennsylvania [Final manuscript, as accepted for Pandya, J.Z., Mora, R.A., Alford, J., Golden, N.A., & de Roock, R.S. (Eds.), The Handbook of Critical Literacies. Routledge, November 2020] Abstract This chapter considers the place of critical literacy research, teaching, and practice in relation to an emerging media environment characterized by digital platforms and datafication. We outline key ideas associated with platform studies and Big Data, and highlight where current frames for critical literacy align with these concepts. We also contend that platforms and datafication present a challenge for critical literacy scholars and practitioners: while critical literacy is valuable for identifying and analyzing many facets of digital activity, it can strain to explain or intervene in the emergent interplay of social, technical, and economic dimensions that animate digital platforms. Rather than undermining the project of critical literacy, we suggest that these limitations offer an opportunity to clarify the place of critical literacy within a wider repertoire of tactics for mapping, critiquing, and transforming digital ecosystems. We offer some implications such a stance might hold for research, teaching, social action, and practice. Introduction In this chapter, we examine key ideas associated with platform studies and datafication, and their relation to critical literacy. We contend that platform technologies present a challenge for critical literacy scholars: while critical literacy is a powerful resource for identifying and analyzing certain digital practices, it can strain to explain or intervene in the broader social, technical, and economic forces whose entanglements animate digital platforms. -

Critical Literacy

CRITICAL LITERACY: WHAT’S WRITING GOT TO DO WITH IT? Barbara Kamler, Deakin University Based on Keynote address for The English Teachers Association of Queensland State Conference, Marist Brothers College Ashgrove, Queensland August 16, 2002 My address is entitled Critical Literacy: What’s Here the slippage from ‘writing and reading’ Writing Got to Do With It? If I were to give a to ‘reading practices’ is fairly seamless and succinct reply to this question, I could offer three is symptomatic, I would argue, of a broader words. On the one hand, I would say ‘Everything’ tendency for literacy to get read as reading (one word) because I believe writing is central or enacted as reading practices. In Barbara to the project of critical literacy and that a Comber’s (1994) important text on critical critical approach to student writing can make a literacy, she argues that in practice, critical difference - to student’s capacity to understand literacy involves at least three principles for and manipulate both the stories of their lives and action: the genres of schooling. • Repositioning students as researchers of On the other hand, I would say ‘Not enough’ language (two words) because in classrooms where • Respecting student resistance and teachers are enacting critical literacy as part exploring minority culture constructions of a repertoire of literacy practices, the focus of literacy and language use has been more deliberately on reading than writing. So, too, in the research literature, where • Problematising classroom and public academics examine what critical literacy means texts. in early childhood, middle years, high school I would add that in practice, these principles and adult literacy contexts. -

Implementing Critical Literacy Pedagogy

IMPLEMENTING CRITICAL LITERACY PEDAGOGY Implementing Critical Literacy Pedagogy to Pose Challenges and Responses of Elementary School Learners By: Nicole Pittman A research paper submitted in conformity with the requirements For the degree of Master of Teaching Department of Curriculum, Teaching and Learning Ontario Institute for Studies in Education of the University of Toronto Copyright by Nicole Pittman, April 2016 1 IMPLEMENTING CRITICAL LITERACY PEDAGOGY Abstract This case study was designed for the purpose of answering the following research question: how do elementary school teachers implement critical literacies in order to pose critical challenges and responses of learners in the twenty-first century? Using qualitative research methods I conducted semi-structured interviews to gain insight to whether practices and teacher prompts of critical thinking proposed by the recent curriculum documents of the Ontario Ministry of Education are working for my participants. An in-depth literature review and three face-to-face, open-ended interviews brought forth data that highlighted four key themes including: 1.) Constructing Student Identities, 2.) Teacher Critical Pedagogy, 3.) Differentiating the Classroom Environment, and 4.) Supporting Inquiry Based Learning. The accumulation of themes was integrated into a discussion of the research findings, providing recommended strategies and areas for future research. By implementing critical literacies in the classroom, students learn to exist in the world through deeper involvement and engagement of content, leading towards greater social action that has the potential to transform environments of the school and their society. All of my participants along with supporting literature gathered suggest that teachers can foster the kind of inquiry and discussions necessary in a critical literacy program by building safe, inclusive classroom cultures that promote student inquiry. -

Gee's Theory of D/Discourse and Research in Teaching English As A

Gee’s Theory of D/discourse and Research in Teaching English as a Second Language: Implications for the Mainstream Tim MacKay University of Manitoba MacKay, T. Gee’s Theory of D/discourse and ESL 1 In this paper I will undertake an exploration of James Paul Gee’s theory of D/discourses and discuss the relevance of this theory to current research in the fields of second language acquisition (SLA) and teaching English as a second language (TESL/ESL). In doing so, I will elaborate on Gee’s theory of D/discourse and will focus on Gee’s discussion of how D/discourses may be acquired. Following this, I will explore some of the parallels that exist between Gee’s theory and current research in SLA and TESL, and by doing so, will demonstrate how certain conditions are required for D/discourse acquisition to occur in the manner theorized by Gee. My intention is to use Gee’s theory and TESL research to suggest that schools and classrooms with students from minority language backgrounds need to carefully consider the social contexts in which these students are integrated. I also intend to show how Gee’s theory and TESL research provide support for the notion that, for effective language learning and academic achievement to occur for ESL learners, pedagogical interventions need to target students who are first language speaker of English in order to enhance ESL students’ opportunities to learn and integrate into the classroom. Gee’s Theory of D/discourses Linguistic theory has always played a significant role in the formulation of theories for second language acquisition (for summaries see, Beebe, 1988; Ellis, 1985; Fitzgerald Gersten & Hudelson, 2000; Spolsky, 1989). -

Cultivating Layered Literacies: Developing the Global Child to Become Tomorrow’S Global Citizen

International Journal of Shulsky, D.D., Baker, S.F., Chvala, T. and Willis, J.M. (2017) ‘Cultivating Development Education and Global Learning layered literacies: Developing the global child to become tomorrow’s global citizen’. International Journal of Development Education and Global Learning, 9 (1): 49–63. DOI 10.18546/IJDEGL.9.1.05. Cultivating layered literacies: Developing the global child to become tomorrow’s global citizen Debra D. Shulsky, Sheila F. Baker, Terry Chvala and Jana M. Willis* – University of Houston–Clear Lake, USA Abstract Disappearing cultural, political and physical boundaries push humanity beyond a one-community perspective. Global citizenry requires a set of literacies that affect the ability to communicate effectively, think critically and act conscientiously. This challenges educators to consider reframing instructional practices and curricular content. The authors promote a transliterate approach spanning communication platforms, including layered literacies: critical, civic, collaborative, creative, cultural, digital, environmental, financial, and geographical. Promoting layered literacies provides a landscaped view of reality (featuring a depth and breadth of knowledge and understanding that cultivates culturally sensitive communication skills), increases critical thinking and empowers learners as agents of change. The authors advocate for a paradigm from which teachers can construct curriculum, meet the challenges of a global community and cultivate layered literacies. Keywords: literacy; global citizenship; -

Building Literacy Communities of Those Actions, Would Garner Intense Analytical Scrutiny

BUILDING LITERACY COMMUNITIES The Thirty-Second Yearbook A Doubled Peer Reviewed Publication ofThe Association of Literacy Educators and Researchers Co-Editors Susan Szabo Timothy Morrison Texas A&M University-Commerce Brigham Young University Merry Boggs Linda Martin Texas A&M University-Commerce Ball State University Editorial Assistant Guest Co-Editor Luisa Frias I. LaVerne Raine Texas A&M University-Commerce Texas A&M University-Commerce Copyright 2010 Association of Literacy Educators and Researchers Photocopy/reprint Permission Statement: Permission is hereby granted to professors and teachers to reprint or photocopy any article in the Yearbook for use in their classes, provided each copy of the ar- ticle made shows the author and yearbook information sited in APA style. Such copies may not be sold, and further distribution is expressly prohibited. Except as authorized above, prior written permission must be obtained from the Associa- tion of Literacy Educators and Researchers to reproduce or transmit this work or portions thereof in any other form or by another electronic or mechanical means, including any information storage or retrieval system, unless expressly permitted by federal copyright laws. Address inquiries to the Association of Literacy Educa- tors and Researchers (ALER), Dr. David Paige, School of Education, Bellarmine University, 2001 Newburg Road, Louisville, KY 40205 ISBN: 1-883604-16-8 Printed at Texas A&M University-Commerce Cover Design: Crystal Britton, student at Texas A&M University-Commerce ii OFFICERS AND ELECTED BOARD MEM B ERS Executive Officers 2008-2009 President: Mona W. Matthews, Georgia State University President-Elect: Laurie Elish-Piper, Northern Illinois University Vice President: Mary F. -

The Practice and Principles of Teaching Critical Literacy at the Educational Video Center

Blackwell Publishing Ltd.Oxford, UK and Malden, USAYSSEThe Yearbooks for the Society of the Study of Education0077-57622004 Blackwell Publishing Ltd20051041 Part Two: Doing Media Literacy in the Schoolsteaching critical literacy at the evcgoodman chapter 11 The Practice and Principles of Teaching Critical Literacy at the Educational Video Center steven goodman We did a documentary about homeless youth . It was an important topic for us to learn and research about because it will change not only the way we think about it, but whoever watches the video will also change their way of thinking about it. And it’s gonna make a difference in people’s lives. —(Vanessa, EVC Documentary Workshop) Overall, what I’ve learned from EVC and what I will take with me, is basically not only working with the camera and things like that and making a documentary, but all in all, how to go out and meet people. And how talk to people. —(Serena, EVC Documentary Workshop) Dialogue is the encounter between men, mediated by the world, in order to name the world. —Paulo Freire (1970, p. 69) Four high school students walk down a mid-Manhattan street as they talk excitedly about who will conduct the first interview. They have generated good questions to ask concerning the problem of homeless youth in New York City, but are not quite sure if anyone will stop to answer them. They pause at a street corner and work awkwardly to disentangle the cables connecting the digital video camera, microphone, and headphones they are holding. Once they sort out their equipment and their crew roles, the book bag and the camera change hands. -

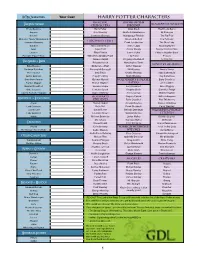

Harry Potter Characters

Lo T R C h a r a c t e r s Your Cast Harry Potter Characters Principal Order of the Hogwarts Denizens The Fellowship Characters Phoenix Frodo Baggins Harry Potter Sirius Black The Bloody Baron Aragorn Ron Weasley Aberforth Dumbledore Sir Cadogan Boromir Hermione Granger Mundungus Fletcher The Fat Friar Meriadoc "Merry" Brandybuck Alice Longbottom The Fat Lady Hogwarts Staff Samwise Gamgee Frank Longbottom The Grey Lady Gandalf Albus Dumbledore Remus Lupin Moaning Myrtle Gimli Argus Filch Alastor Moody Nearly Headless Nick Legolas Filius Flitwick James Potter Phineas Nigellus Black Peregrin "Pippin" Took Wilhelmina Grubbly-Plank Lily Potter Peeves Rubeus Hagrid Kingsley Shacklebolt Sorting Hat The Shire & Bree Rolanda Hooch Nymphadora Tonks Ministry of Magic Bilbo Baggins Gilderoy Lockhart Arthur Weasley Barliman Butterbur Minerva McGonagall Bill Weasley Amelia Bones Rosie Cotton Irma Pince Charlie Weasley Mary Cattermole Gaffer Gamgee Poppy Pomfrey Molly Weasley Reg Cattermole Bree Gate Keeper Quirinus Quirrell Voldemort & Death Barty Crouch Sr Farmer Maggot Horace Slughorn Eaters John Dawlish Everard Proudfoot Severus Snape Lord Voldemort Amos Diggory Otho Sackville Pomona Sprout Regulus Black Cornelius Fudge Lobelia Sackville-Baggins Sybill Trelawney Alecto Carrow Mafalda Hopkirk Hogwarts Amycus Carrow Rufus Scrimgeour Rivendell & Lothlórien Students Barty Crouch Jr Pius Thicknesse Arwen Hannah Abbott Antonin Dolohov Dolores Umbridge Lord Celeborn Katie Bell Fenrir Greyback Percy Weasley Lord Elrond Susan Bones Bellatrix Lestrange Wizarding World Lady Galadriel Lavender Brown Walden Macnair Citizens Haldir Millicent Bulstrode Lucius Malfoy Bathilda Bagshot Cho Chang Narcissa Malfoy Mr Borgin Creatures Vincent Crabb Peter Pettigrew Ariana Dumbledore Shelob Colin Creevey Foreign wizards & Food Trolley Lady The Balrog - Durin's Bane Cedric Diggory witches Auntie Muriel Justin Finch-Fletchley Fleur Delacour Xenophilius Lovegood Other Characters Marcus Flint Gabrielle Delacour Mr. -

Introduction Introduction

xi Introduction Introduction Reconceptua- Over the years our definitions of literacy have changed. Although historical accounts and outlines chronicling these changes have lizing Literacy appeared in print (Myers, 1996; Smith & Lambert Stock, 2003; and Literacy Rosenblatt, 2003; Squire, 2003), there is no end to the process of change and so we continue to learn and add to this history. As we Teaching understand more about language and literacy, our conception of literacy changes and with it, ideally, our instructional practices. For example, we used to think about literacy as a commodity: a set of useful skills that you either had or didn’t have and for which differ- ent teaching pedagogies and materials were developed, bought, and sold. During the mid-1990s, for instance, “[T]he differences among factions in the reading field resulted in fragmentation, disarray and division” (Dole & Osborn, 2003). The field was polarized along a number of dimensions; for example, phonics versus whole language, explicit versus implicit instruction, skills versus strategies, textbooks versus trade books, predictable versus decodable books, and reading groups versus literature circles (Graves, 1998). More recently we have begun to think of literacy as sets of social practices. Social practices are particular ways of doing and being as well as particular ways of acting and talking that are rooted in life experiences. Since different people have different life experi- ences it follows that social practices are differentially available to various individuals and groups of people. This differential availabil- ity means that not everyone has equitable or equal access to literacy. Conceptualizing literacy as social practices further implies that different cultures value and have access to different literacies or malleable sets of cultural practices, that is, a community’s ways of being and doing. -

Project Name Developing a Sunywide Transliteracy Learning

Project Name Developing a SUNYwide Transliteracy Learning Collaborative to Promote Information and Technology Collaboration Principal Investigator Trudi Jacobson Campus Albany, University at Year of Project 2012 Tier Tier Three Project Team ● Thomas Mackey, Empire State College ● Mark McBride, Buffalo State ● Michael Daly, Fulton Montgomery Community College ● Michele Forte, Empire State College ● Jenna Hecker, University at Albany ● Ellen Murphy, Empire State College Overview Summary Creation of a Transliteracy Learning Collaborative as a SUNYwide think tank and incubator for promoting transliteracy and emerging frameworks for information literacy including learning analytics, badges, and the semantic web. Other areas of exploration include the transition from high school to college, and developing learning communities. Outcomes Summary Robust resources are provided on the website to guide student in understanding of metaliteracy. There is also an Open SUNY Textbook available to assist with Metaliteracy. Project Abstract The proposed Transliteracy Learning Collaborative (TLC) will be a SUNYwide think tank and incubator for promoting transliteracy and emerging frameworks for information literacy (IL). TLC will transcend boundaries based upon the traditional definition of information literacy and the concept of librarians as the sole interested party. This grant will establish SUNY in the forefront of higher education institutions committed to developing students as lifelong creators of information in all forms. It will address how to infuse transliteracy throughout students’ academic careers, opening dialogues among different educational groups, and exploring issues such as learning analytics, badges, and the semantic web. TLC will solicit participants to serve on 56 teams that will address key components of a systemwide transliteracy initiative. -

The New Literacies Narrative Amanda Sladek

The New Literacies Narrative Amanda Sladek ... literacy is always plural: literacies (there are many of them ... and we all have some and fail to have others).... —James Paul Gee I've been teaching a version of the literacy narrative for several years. In my first attempt, I taught the assignment as outlined by Anne Beaufort: a short narrative essay centered on the topic of the writer's experience reading and writing (187). Susan DeRosa notes that "students' literacy narratives could provide a space for them to rewrite versions of their literacy experiences and events," allowing them to become "active participants in the construction of their literacy development" in order to "challenge prescriptive ideas about literacy" (2). When I taught this assignment for the first time, though, that didn't happen. The unit wasn't a disaster, mind you. Several students wrote great literacy narratives, and many of them said they appreciated the oppor tunity to write about their lives. It just... fell a little flat. I had a hard time getting students to fully engage with their literacy experiences, let alone challenge their preconceived notions of literacy. While responding to my students' papers, I quickly identified a pattern I call the "literacy narrative arc": students provide an anecdote about their early love for reading; then, they describe a high school teacher who extinguished their natural thirst for literacy by assigning The Scarlet Letter; finally, they close with a general statement about the importance of literacy (they are writing for an English teacher, after all). I'm astonished by the number of papers that follow this arc, and not just because I liked The Scarlet Letter.