“Magic Is Might” Reading the Harry Potter Heptalogy Through a Dystopian Lens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Many Faces of Albus Dumbledore in the Setting of Fan Writing

MANY FACES OF ALBUS DUMBLEDORE IN THE SETTING OF FAN WRITING: THE TRANSFORMATION OF READERS INTO “READER-WRITERS” AND THE IMPLICATIONS OF THEIR PRESENCE IN THE AGE OF ONLINE FANDOM by Midori Fujita A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in The Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies (Children’s Literature) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) October 2014 © Midori Fujita, 2014 ii Abstract This thesis examines the dynamic and changing nature of reader response in the time of online fandom by examining fan reception of, and response to, the character Dumbledore in J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series. Using the framework of reader reception theory established by Wolfgang Iser, in particular Iser’s conception of textual indeterminacies, to construct my critical framework, this work examines Professor Albus Dumbledore as a case study in order to illuminate and explore how both the text and readers may contribute to the identity formation of a single character. The research examines twenty-one selected Internet-based works of fan writing. These writings are both analytical and imaginative, and compose a selection that illuminates what aspect of Dumbledore’s characters inspired readers’ critical reflection and inspired their creative re-construction of the original story. This thesis further examines what the flourishing presence of Harry Potter fan community tells us about the role technological progress has played and is playing in reshaping the dynamics of reader response. Additionally, this research explores the blurring boundaries between authors and readers in light of the blooming culture of fan fiction writing. -

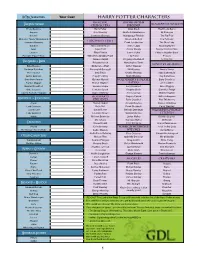

Harry Potter Characters

Lo T R C h a r a c t e r s Your Cast Harry Potter Characters Principal Order of the Hogwarts Denizens The Fellowship Characters Phoenix Frodo Baggins Harry Potter Sirius Black The Bloody Baron Aragorn Ron Weasley Aberforth Dumbledore Sir Cadogan Boromir Hermione Granger Mundungus Fletcher The Fat Friar Meriadoc "Merry" Brandybuck Alice Longbottom The Fat Lady Hogwarts Staff Samwise Gamgee Frank Longbottom The Grey Lady Gandalf Albus Dumbledore Remus Lupin Moaning Myrtle Gimli Argus Filch Alastor Moody Nearly Headless Nick Legolas Filius Flitwick James Potter Phineas Nigellus Black Peregrin "Pippin" Took Wilhelmina Grubbly-Plank Lily Potter Peeves Rubeus Hagrid Kingsley Shacklebolt Sorting Hat The Shire & Bree Rolanda Hooch Nymphadora Tonks Ministry of Magic Bilbo Baggins Gilderoy Lockhart Arthur Weasley Barliman Butterbur Minerva McGonagall Bill Weasley Amelia Bones Rosie Cotton Irma Pince Charlie Weasley Mary Cattermole Gaffer Gamgee Poppy Pomfrey Molly Weasley Reg Cattermole Bree Gate Keeper Quirinus Quirrell Voldemort & Death Barty Crouch Sr Farmer Maggot Horace Slughorn Eaters John Dawlish Everard Proudfoot Severus Snape Lord Voldemort Amos Diggory Otho Sackville Pomona Sprout Regulus Black Cornelius Fudge Lobelia Sackville-Baggins Sybill Trelawney Alecto Carrow Mafalda Hopkirk Hogwarts Amycus Carrow Rufus Scrimgeour Rivendell & Lothlórien Students Barty Crouch Jr Pius Thicknesse Arwen Hannah Abbott Antonin Dolohov Dolores Umbridge Lord Celeborn Katie Bell Fenrir Greyback Percy Weasley Lord Elrond Susan Bones Bellatrix Lestrange Wizarding World Lady Galadriel Lavender Brown Walden Macnair Citizens Haldir Millicent Bulstrode Lucius Malfoy Bathilda Bagshot Cho Chang Narcissa Malfoy Mr Borgin Creatures Vincent Crabb Peter Pettigrew Ariana Dumbledore Shelob Colin Creevey Foreign wizards & Food Trolley Lady The Balrog - Durin's Bane Cedric Diggory witches Auntie Muriel Justin Finch-Fletchley Fleur Delacour Xenophilius Lovegood Other Characters Marcus Flint Gabrielle Delacour Mr. -

Harry Potter Resource Guide for Fans

Prepared by Janan Nuri May 2020 Module: INM307 Sending out owls to all fans of Harry Potter Whether you’re a die-hard Potterhead, a fan who loves the movies, or a pure-blood who sticks to the books, there’s something here for you. This resource guide is a starting point for exploring more of the Harry Potter series and J.K. Rowling’s Wizarding World, which is a vast universe in canon and in fandom. You’ll find resources listed, followed by a short description of what to expect from them, and why they’re worth checking out. Even though this guide is geared towards fans based in the UK, there are plenty of online resources to connect you with others around the world. The focus is more on the Harry Potter series, though the Fantastic Beasts series and The Cursed Child play are also included. Marauders’ Mapping the Way Don’t worry, you won’t need your wand to cast Lumos to illuminate the way, this guide has been designed to be as simple and straightforward to navigate as possible. There are hyperlinks in the Contents and in the text to jump to relevant parts of the guide. The guide has four sections, ‘Exploring the Canon’, ‘Exploring the Fandom’, ‘Places to Visit’ and a ‘Shopping Guide’ for fans who visit London UK, the location of Diagon Alley in the series. There’s also a ‘Glossary’ at the end, explaining common fan phrases (if you’re not sure what ‘canon’ and ‘fandom’ means, then have a quick peek now). -

Erps Reveal Retrieval of Domain and Specific Knowledge During

Harry Potter and the language-knowledge interface: ERPs reveal retrieval of domain and specific knowledge during reading Melissa Troyer and Marta Kutas (UCSD) [email protected] Across cognitive systems, world knowledge allows individuals to organize raw sensation into meaningful experiences. Language processing is no exception—words cue world knowledge which can be rapidly brought to mind in real time. It stands to reason that how much and how well individuals know things will impact what each individual brings to mind during real-time comprehension; yet to date, models of real-time language processing have not taken this variability into account. We addressed this issue by studying a linguistically rich, yet constrained, popular domain—the fictional world of Harry Potter (HP), by J.K. Rowling. In a series of three studies (Experiment 1 reported in [1]), we recorded event-related brain potentials (ERPs) while young adults who varied in their knowledge of HP read sentences about HP “facts” and/or sentences describing general topics (Table 1). As a measure of real-time knowledge retrieval, we focused on N400 amplitude, a brain potential with a centro-parietal maximum occurring ~250-500 ms post stimulus onset that is sensitive to factors impacting the ease of retrieval from semantic memory, with larger reductions in N400 (i.e., more positive-going N400 potentials) associated with greater ease of retrieval [2]. Across all three studies, we found that individuals’ domain knowledge of HP (assessed via an offline multiple-choice trivia quiz; details in [1]) was moderately-to-strongly correlated with average N400 brain potentials to contextually supported (i.e., accurate) words completing sentences about HP, but not to unsupported (inaccurate) endings, nor to N400 effects (i.e., difference ERPs) of more vs. -

The Case of Harry Potter

Reimagining Religion in a Contemporary Context: The Case of Harry Potter Natania Bloch Program in Jewish Studies November 3, 2020 Thesis Advisor: Elias Sacks, Program in Jewish Studies & Department of Religious Studies Honors Council Representative: Samuel Boyd, Program in Jewish Studies & Department of Religious Studies Committee Members: Susan Kent, Department of History Samira Mehta, Program in Jewish Studies & Department of Women and Gender Studies “After all, to the well-organized mind, death is but the next great adventure.” -Albus Dumbledore For Athena-- Thank you for lighting my divine spark. זיכרונו לברכה 1 Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................................................................................. 3 PREFACE ......................................................................................................................................................................... 4 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................................. 5 CHAPTER ONE: A JEWISH PERSPECTIVE ON RELIGION ................................................................................................. 10 INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................................................... 10 JUDITH PLASKOW .................................................................................................................................................... -

Harry Potter : the Creature Vault Pdf, Epub, Ebook

HARRY POTTER : THE CREATURE VAULT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jody Revenson | 208 pages | 26 Sep 2016 | Titan Books Ltd | 9781783296019 | English | London, United Kingdom Harry Potter : The Creature Vault PDF Book The thing that really sets the two books apart is the focus of the content. TCV boasts an impressive 9 chapters and features 39 different creatures and plants. Author Jody Revenson has provided an insightful writeup that talks about their designs for the movies, the story component and interesting details such as the technical parts on how the creatures were created, be it in computer or real life. The following month, she announced via the site that members of the Harry Potter world — and celebrity fans — would each take a turn reading one of the chapters from the first book and the videos would live online. Playing quidditch. More MuggleNet Articles We simply strive to provide students and professionals with the lowest prices on books and textbooks available online. The Marauder's Map. Remus Lupin. I've been lucky in life and can attribute a lot of that to Harry Potter. We strive to be fair and honest with all of our customers and we make your satisfaction our top priority, including listening to each of our customers as to what they feel is the fair thing to do in unique return situations. LEGO video games are extremely popular, so when you combine that appeal with the world of Harry Potter, the end result would have to be worth playing. We send trivia questions and personality tests every week to your inbox. -

6 Harry Potter Fanfiction

Univerzita Hradec Králové Pedagogická fakulta Katedra anglického jazyka a literatury Vývoj vedlejších postav ságy Harryho Pottera ve fanfiction Development of Minor Characters from Harry Potter Saga in Fanfiction Diplomová práce Autor: Bc. Anna Fólová Studijní program: N7504 Učitelství pro střední školy Studijní obor: Učitelství pro střední školy – hudební výchova, Učitelství pro 2. stupeň ZŠ – anglický jazyk a literatura Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Jan Suk, Ph.D. Hradec Králové 2019 Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto bakalářskou práci vypracovala samostatně a uvedla jsem všechny použité prameny a literaturu. V Hradci Králové dne 1.4.2019 Anotace FÓLOVÁ, Anna. Vývoj vedlejších postav ságy Harryho Pottera ve fanfiction. Hradec Králové: Pedagogická fakulta Univerzity Hradec Králové, 2019. 63 s. Diplomová práce. Tato práce představuje fanfikci a fanouškovskou tvorbu obecně. Uvádí její historický vývoj, reakce spisovatelů děl, podle kterých fanfikce vzniká a problémy s legální stránkou fanfikce. Popisuje fandom Harryho Pottera a jeho specifika, fandom také porovnává s fandomy ostatních děl převážně fantasy a science-fiction literatury. V praktické části potom analyzuje dvojici vybraných postav a jejich vývoj, které popisuje nejprve z pohledu původního díla, poté z pohledu fanfikce a posléze vývoj porovnává a shrnuje. Klíčová slova: Harry Potter, Fanfiction, Fandom, Vedlejší postavy. Annotation FÓLOVÁ, Anna. Development of Minor Characters from Harry Potter Saga in Fanfiction. Hradec Králové: Pedagogical Faculty, University of Hradec Králové, 2019, 63 pp. Diploma dissertation. This thesis presents fanfiction and fanwork in general. It introduces its historical development, reaction of the original work authors´ and legal issues of fanfiction. This thesis describes fandom of Harry Potter and its particularities, compares it with other fandoms, mostly fantasy and science fiction works. -

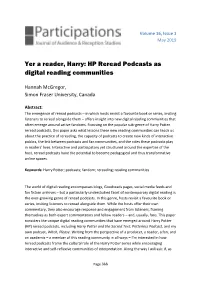

Yer a Reader, Harry: HP Reread Podcasts As Digital Reading Communities

. Volume 16, Issue 1 May 2019 Yer a reader, Harry: HP Reread Podcasts as digital reading communities Hannah McGregor, Simon Fraser University, Canada Abstract: The emergence of reread podcasts – in which hosts revisit a favourite book or series, inviting listeners to reread alongside them – offers insight into new digital reading communities that often emerge around active fandoms. Focusing on the popular sub-genre of Harry Potter reread podcasts, this paper asks what lessons these new reading communities can teach us about the practice of rereading, the capacity of podcasts to create new kinds of interactive publics, the link between podcasts and fan communities, and the roles these podcasts play in readers’ lives. Interactive and participatory yet structured around the expertise of the host, reread podcasts have the potential to become pedagogical and thus transformative online spaces. Keywords: Harry Potter; podcasts; fandom; rereading; reading communities The world of digital reading encompasses blogs, Goodreads pages, social media feeds and fan fiction archives – but a particularly understudied facet of contemporary digital reading is the ever-growing genre of reread podcasts. In this genre, hosts revisit a favourite book or series, inviting listeners to reread alongside them. While the hosts offer their own commentary, they also encourage response and engagement from listeners, framing themselves as both expert commentators and fellow readers – and, usually, fans. This paper considers the unique digital reading communities that have emerged around Harry Potter (HP) reread podcasts, including Harry Potter and the Sacred Text, Potterless Podcast, and my own podcast, Witch, Please. Writing from the perspective of a producer, a reader, a fan, and an academic – a member of this reading community in all ways – I’m interested in how reread podcasts frame the cultural role of the Harry Potter series while encouraging interactive and self-reflexive communities of interpretation. -

Community and Gift Economy in Harry Potter Fanfiction

Minnesota State University, Mankato Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato All Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects Projects 2020 Comments, Gifts and Kudos: Community and Gift Economy in Harry Potter Fanfiction Deanna Almquist Minnesota State University, Mankato Follow this and additional works at: https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/etds Part of the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Almquist, D. (2020). Comments, gifts and kudos: Community and gift economy in Harry Potter fanfiction [Master's thesis, Minnesota State University, Mankato]. Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/etds/963/ This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects at Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. COMMENTS, GIFTS AND KUDOS: COMMUNITY AND GIFT ECONOMY IN HARRY POTTER FANFICTION By Deanna Almquist A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science In Applied Anthropology Minnesota State University, Mankato Mankato, Minnesota May 2020 i November 4, 2019 Comments, Gifts and Kudos: Community and Gift Economy in Harry Potter Fanfiction Deanna Almquist This thesis has been examined and approved by the following members of the student’s committee. Dr. Rhonda Dass___________________ Advisor Dr. Susan Schalge__________________ Committee Member Dr. -

“Harry – Yer a Wizard” Exploring J

Wissenschaftliche Beiträge aus dem Tectum Verlag Reihe Anglistik Wissenschaftliche Beiträge aus dem Tectum Verlag Reihe Anglistik Band 6 Marion Gymnich | Hanne Birk | Denise Burkhard (Eds.) “Harry – yer a wizard” Exploring J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter Universe Tectum Verlag Marion Gymnich, Hanne Birk and Denise Burkhard (Eds.) “Harry – yer a wizard” Exploring J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter Universe Wissenschaftliche Beiträge aus demT ectum Verlag, Reihe: Anglistik; Bd. 6 © Tectum Verlag – ein Verlag in der Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden 2017 ISBN: 978-3-8288-6751-2 (Dieser Titel ist zugleich als gedrucktes Werk unter der ISBN 978-3-8288-4035-5 und als ePub unter der ISBN 978-3-8288-6752-9 im Tectum Verlag erschienen.) ISSN: 1861-6859 Umschlaggestaltung: Tectum Verlag, unter Verwendung zweier Fotografien von Schleiereule Merlin und Janna Weinsch, aufgenommen in der Falknerei Pierre Schmidt (Erftstadt/Gymnicher Mühle) | © Denise Burkhard Informationen zum Verlagsprogramm finden Sie unter www.tectum-verlag.de Bibliografische Informationen der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Angaben sind im Internet über http://dnb.ddb.de abrufbar. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available online at http://dnb.ddb.de. Contents Hanne Birk, Denise Burkhard and Marion Gymnich ‘Happy Birthday, Harry!’: Celebrating the Success of the Harry Potter Phenomenon ........ 7 Marion Gymnich and Klaus Scheunemann The ‘Harry Potter Phenomenon’: Forms of World Building in the Novels, the Translations, the Film Series and the Fandom ................................................................. 11 Part I: The Harry Potter Series and its Sources Laura Hartmann The Black Dog and the Boggart: Fantastic Beasts in Joanne K. -

Professor Dumbledore's Advice for Law Deans, 39 U

UIC School of Law UIC Law Open Access Repository UIC Law Open Access Faculty Scholarship 2008 Professor Dumbledore's Advice for Law Deans, 39 U. Tol. L. Rev. 269 (2008) Darby Dickerson John Marshall Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.uic.edu/facpubs Part of the Legal Education Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Recommended Citation Darby Dickerson, Professor Dumbledore's Advice for Law Deans, 39 U. Tol. L. Rev. 269 (2008) https://repository.law.uic.edu/facpubs/640 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UIC Law Open Access Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UIC Law Open Access Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of UIC Law Open Access Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PROFESSOR DUMBLEDORE'S ADVICE FOR LAW DEANS Darby Dickerson* INTRODUCTION LBUS Percival Wulfric Brian Dumbledore.' Adorned with a long silver beard, midnight blue robes, and half-moon glasses,2 Dumbledore * Vice President and Dean, Stetson University College of Law. I would like to thank my research assistant, Casey Stoutamire, for her work on this piece, and my colleague, Professor Brooke Bowman, for her editing assistance. Also, as the author of the ALWD Citation Manual, I want to thank the University of Toledo Law Review editors for keeping my citations in that format and for allowing me to dispense with some traditional citation niceties, such as the "supra n. _, at " construction for books in the Harry Potter series and the strict use of id., so that readers can more easily locate the sources cited. -

An Ethnography of Harry Potter Fans

UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Trust, Friendship and Hogwarts Houses: An Ethnography of Harry Potter Fans by Heather Victoria Dunphy A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY CALGARY, ALBERTA September 2011 © Heather Victoria Dunphy 2011 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre refdrence ISBN: 978-0-494-81404-8 Our file Notre r6f6rence ISBN: 978-0-494-81404-8 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation.