A Short History of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Service in the Australian Army Or Noah Riseman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Periodicals and Recurring Documents

PERIODICALS AND RECURRING DOCUMENTS May 2012 Legend A ANNUAL S-M SEMI-MONTHLY D DAILY BI-M BI-MONTHLY W WEEKLY Q QUARTERLY BI-W BI-WEEKLY TRI-A TRI-ANNUAL M MONTHLY IRR IRREGULAR S-A SEMI-ANNUAL A ACADEME. (BI-M) 1985-1989 ACADEMY OF POLITICAL SCIENCE. PROCEEDINGS. (IRR) 1960-1991 (MFILM 1975-1980) (MFICHE 1981-1982) ACQUISITION REVIEW QUARTERLY. (Q) 1994-2003 CONTINUED BY DEFENSE ACQUISITION REVIEW JOURNAL. AD ASTRA-TO THE STARS. (M) 1989-1992 ADA. (Q) 1991-1997 FORMERLY AIR DEFENSE ARTILLERY. ADF: AFRICA DEFENSE FORUM. (Q) 2008- ADVANCE. (A) 1986-1994 ADVANCED MANAGEMENT JOURNAL. SEE S.A.M. ADVANCED MANAGEMENT JOURNAL. ADVISOR. (Q) 1974-1978 FORMERLY JOURNAL OF NAVY CIVILIAN MANPOWER MANAGEMENT. ADVOCATE. (BI-M) 1982-1984 - 1 - AEI DEFENSE REVIEW. (BI-M) 1977-1978 CONTINUED BY AEI FOREIGN POLICY AND DEFENSE REVIEW. AEI FOREIGN POLICY AND DEFENSE REVIEW. (BI-M) 1979-1986 FORMERLY AEI DEFENSE REVIEW. AEROSPACE. (Q) 1963-1987 AEROSPACE AMERICA. (M) 1984-1998 FORMERLY ASTRONAUTICS & AERONAUTICS. AEROSPACE AND DEFENSE SCIENCE. (Q) 1990-1991 FORMERLY DEFENSE SCIENCE. AEROSPACE HISTORIAN. (Q) 1965-1988 FORMERLY AIRPOWER HISTORIAN. CONTINUED BY AIR POWER HISTORY. AEROSPACE INTERNATIONAL. (BI-M) 1967-1981 FORMERLY AIR FORCE SPACE DIGEST INTERNATIONAL. AEROSPACE MEDICINE. (M) 1973-1974 CONTINUED BY AVIATION SPACE AND EVIRONMENTAL MEDICINE. AEROSPACE POWER JOURNAL. (Q) 1999-2002 FORMERLY AIRPOWER JOURNAL. CONTINUED BY AIR & SPACE POWER JOURNAL. AEROSPACE SAFETY. (M) 1976-1980 AFRICA REPORT. (BI-M) 1967-1995 (MFICHE 1979-1994) AFRICA TODAY. (Q) 1963-1990; (MFICHE 1979-1990) 1999-2007 AFRICAN SECURITY. (Q) 2010- AGENDA. (M) 1978-1982 AGORA. -

Indigenous Australians Brochure

SEE YOURSELF IN A REWARDING ROLE CHOOSE A JOB IN A DIVERSE AND SUPPORTIVE WORKPLACE A CONTRIBUTE TO YOUR COUNTRY’S DEFENCE THE AUSTRALIAN DEFENCE FORCE (ADF) IS AN EMPLOYER OF CHOICE FOR HUNDREDS OF INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIANS. Help maintain a proud tradition of service by joining the thousands of Indigenous men and women who for over 100 years, have contributed to the protection of our country and its interests as members of the ADF. In the Navy, Army or Air Force, you’ll work alongside Indigenous Australians from across the ranks, enjoying opportunities rarely found in civilian employment. As you serve your country and community, your abilities will be nurtured and given focus. You’ll receive world-class training and be given the opportunity to earn qualifications that will give you the skills, knowledge and experience to reach your full potential in a fulfilling role. 01 FEATURED 04 GET A GREAT JOB AND MORE 08 RECEIVE WORLD-CLASS TRAINING INSIDE AND EDUCATION 09 CHOOSE YOUR IDEAL ROLE 10 ENTER THE WAY YOU WANT TO 14 ACHIEVE YOUR POTENTIAL 16 INDIGENOUS PRE-RECRUIT PROGRAM 18 NAVY INDIGENOUS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM 20 ARMY INDIGENOUS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM 22 AIR FORCE INDIGENOUS DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITIES 26 ACCESS FLEXIBLE ENTRY PATHWAYS 28 HOW TO JOIN 32 CONTACT US 02 03 GET A GREAT JOB AND MORE REWARDING, WELL-PAID WORK IS JUST THE START. AS A FULL-TIME MEMBER OF THE ADF YOU’LL ENJOY: A friendly and supportive team environment that embraces cultural, social and workforce diversity A competitive salary and superannuation Equal pay regardless -

How Did Indigenous Australians Contribute to the Defence Of

How did Indigenous Australians help in the Defence of Australia in World War 2? WHAT DOES THIS TELL US ABOUT CITIZENSHIP? We do not know much about Indigenous service in the Australian armed forces. However, we are now starting to discover more as interest in Australia’s Indigenous history grows. In this unit we have gathered together information and evidence about Indigenous Australians’ service in World War 2, and in particular their involvement in the northern Defence of Australia. By looking at this information and evidence you will be able to explore the two great themes we have been presenting in the Defence 2020 program this year: Citizenship, and Plaque at Rocky Creek, Role Models. Atherton Tablelands, Queensland Your task Indigenous involvement in the Defence of Australia in World War 2 Your task is to look at the sources presented on the next pages, and to use them to answer Who was involved? the sorts of key questions that are part of any What did they do? historical inquiry. You can use a table like this: When did they do it? Conclusion Where did they do it? When you have completed your summary table Why did they do it? from all the sources decide on your answers to these questions: What were the impacts of the involvement? Did Indigenous Australians show good What were the consequences of the involvement? citizenship during the war? Did Indigenous people provide good role models that we could follow today? Further Reading Did non-Indigenous Australians show good citizenship towards Indigenous Australians? Ball, Desmond. Aborigines in the defence of Australia. -

Australian Defence Force's Approach for the Protection of Civilian (POC): Perspectives of Guidelines, Training and WPS Introd

Australian Defence Force’s Approach for the Protection of Civilian (POC): Perspectives of Guidelines, Training and WPS CDR Takashi Kawashima, Japan Peacekeeping Training and Research Center *This document is the translation of research paper in Japanese produced as part of the outreach effort of Japan Peacekeeping Training and Research Center (JPC). Contents Introduction: The Protection of Civilian as the Operational Challenge of Military Force ............... 1 1. The Overview and the Background of Australia’s efforts for POC ............................................. 4 (1) Military Aspect: ADF’s Operational Experiences of POC in East Timor ............................... 4 (2) Policy Aspect-1: Contribution to the POC in International Community ................................. 8 (3) Policy Aspect-2: Promotion of POC in the context of Women, Peace and Security (WPS) 9 2. Specific measures of ADF for promoting the POC ................................................................... 14 (1) Defining Australia’s unified concept of POC: development of the POC Guidelines ........... 14 (2) Development of POC Training Modules .............................................................................. 18 3. POC as the essential element of WPS ..................................................................................... 21 (1) Female Engagement Team (FET) and Gender Advisor (GA) ............................................ 22 (2) Integration of WPS into multilateral joint exercise: Talisman Sabre .................................. -

ORGANISATIONAL CHANGE in the AUSTRALIAN DEFENCE FORCE: TOWARDS a UNIQUE SOLUTION Brigadier Peter J. Dunn, AM Master of Defence S

ORGANISATIONAL CHANGE IN THE AUSTRALIAN DEFENCE FORCE: TOWARDS A UNIQUE SOLUTION Brigadier Peter J. Dunn, AM Master of Defence Studies Sub-Thesis University College The University of New South Wales Australian Defence Force Academy 1994 CONTENTS PARTS 1 PRINCIPAL CHANGES IN AUSTRALIA'S MILITARY COMMAND STRUCTURE SINCE THE 1950s 1 2 ORGANISATIONAL CHANGE THEORY AND REVIEWS OF THE ADF 16 3 A CHANGING ORGANISATIONAL ENVIRONMENT FOR THE ADF- THE NEED TO FOCUS ON "CORE BUSINESS" 27 4 ORGANISATIONAL CHANGE FOR MORE EFFECTIVE ADF OPERATIONS 45 5 CONCLUSIONS 68 BIBLIOGR.\PHY 74 FIGURES 1 LOCBI IN THE PRE-BAKER STUDY ADF 32 2 LOCBI IN THE POST- BAKER STUDY ADF 33 3 OPERATIONAL FLEXIBILITY IN THE ADF STRUCTURE 42 4 MODEL ONE ADF ORGANISATION 53 5 MODEL TWO ADF ORGANISATION 57 6 MODEL THREE ADF ORGANISATION 66 Ill ABSTR.4CT The Australian Defence organisation has been the subject of almost constant review since the 1950s. The first of these major reviews, the Morshead Review was initiated in 1957. This review coincided with the growing realisation that Australia had to become more self reliant in defence matters. The experience of World War Two had shown that total reliance on "great and powerful friends" was a dangerous practice and self reliance dictated that Australia's military forces would have to act together in a joint environment. Australia's system of military command had to be capable of producing effective policies and planning guidance to met the new demands of independent joint operations. Successive reviews aimed at moving the Australian Defence Forces toward a more joint organisation have resulted in major changes to the higher defence machinery. -

The Potential Benefits to the Australian Defence Force Educational Curricula of the Inclusion of Indigenous Knowledge Systems

The Potential Benefits to the Australian Defence Force Educational Curricula of the Inclusion of Indigenous Knowledge Systems Debbie Fiona Hohaia, Master Professional Studies (Aboriginal Studies) Bachelor Education, Diploma Teaching, Diploma Management, Diploma Human Resources, Diploma of Government This thesis is submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Indigenous Knowledges and Public Policy, Charles Darwin University 18 January 2016 Declaration I hereby declare that the work herein, now submitted as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Charles Darwin University, is the result of my own investigations and does not reflect the views and opinions of the Australian Defence Force, the New Zealand Defence Force or any extant policy. All reference to ideas and the work of other researchers have been specifically acknowledged. I hereby certify that the work embodied in this thesis has not already been accepted in substance for any degree, and is not being submitted in candidature for any other degree. I acknowledge that the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (developed by the National Health and Medical Research Council, Australian Research Council and the Australian Vice Chancellors Committee, March 2007) has been adhered to. The work in this thesis was undertaken between the dates of December 2012 to December 2014 and in no way reflects the advancements that have been made by various elements of the Australian Defence Force and the cultural diversity initiatives, which have been embedded within the last 18 months. Full name: Debbie Fiona Hohaia Signed: Date: 18 January 2016 Page I Acknowledgements There are many people who have contributed and participated in this research. -

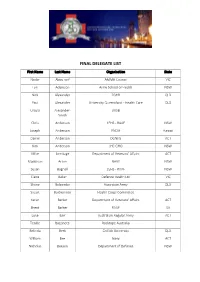

Final Delegate List

FINAL DELEGATE LIST First Name Last Name Organisation State Nader Abou-seif AMMA Council VIC Lyn Adamson Army School of Health NSW Nick Alexander 2GHB QLD Paul Alexander University Queensland - Health Care QLD Ursula Alexander- 3HSB Smith Chris Anderson 1EHS - RAAF NSW Joseph Anderson PACAF Hawaii Daniel Anderson DGNHS ACT Kim Anderson JHC GHO NSW Mike Armitage Department of Veterans' Affairs ACT Maddison Arton NAVY NSW Susan Bagnall 2EHS - RAAF NSW Claire Baker Defence Health Ltd VIC Shane Balcombe Australian Army QLD Stuart Baldwinson Health Corps Committee Karen Barker Department of Veterans' Affairs ACT Brent Barker RAAF SA Luke Barr Australian Regular Army ACT Tenille Bazzinotti Rocktape Australia Belinda Beck Griffith University QLD William Bee Navy ACT Nicholas Beeson Department of Defence NSW Bevan Begeda Philips QLD Daniel Belanszky Army QLD Alan Bell Aware Medical NSW Helen Benassi Department of Defence ACT Clare Bennett New Zealand Defence Force New Zealand Victoria Bensley 3HSB Cecilia Berryman Directorate Navy Health Julie Blackburn Defence Health Foundation ACT Julie Blogg Stirling Health Centre WA Amy Bowden HOCU - RAAF QLD Mark Brazier Department of Defence ACT Jordan Breed RAAF VIC Mackay Brendan Australian Regular Army NSW Leonard Brennan Joint Health Command ACT Di Bridger RAAF NSW Matt Briffa Zoll NSW Jamie Briskey Australian Army Adrian Brooks OPSWO Army School of Health Adam Bryant University of Melbourne VIC Emma Bucknell JHC GHO ACT David Bullock Army QLD Jessica Burton Department of Defence QLD Toni Bushby Australian -

Australian Army Journal Is Published by Authority of the Chief of Army

Australian Army Winter edition 2014 Journal Volume XI, Number 1 • What Did We Learn from the War in Afghanistan? • Only the Strong Survive — CSS in the Disaggregated Battlespace • Raising a Female-centric Battalion: Do We Have the Nerve? • The Increasing Need for Cyber Forensic Awareness and Specialisation in Army • Reinvigorating Education in the Australian Army The Australian Army Journal is published by authority of the Chief of Army The Australian Army Journal is sponsored by Head Modernisation and Strategic Planning, Australian Army Headquarters © Commonwealth of Australia 2014 This journal is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of study, research, criticism or review (as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968), and with standard source credit included, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Contributors are urged to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in their articles; the Editorial Advisory Board accepts no responsibility for errors of fact. Permission to reprint Australian Army Journal articles will generally be given by the Editor after consultation with the author(s). Any reproduced articles must bear an acknowledgment of source. The views expressed in the Australian Army Journal are the contributors’ and not necessarily those of the Australian Army or the Department of Defence. The Commonwealth of Australia will not be legally responsible in contract, tort or otherwise for any statement made in this journal. ISSN 1448-2843 Editorial Advisory Board Prof Jeffrey Grey LTGEN Peter Leahy, AC (Retd) MAJGEN Elizabeth Cosson, AM (Retd) Dr John Blaxland BRIG Justin Kelly, AM (Retd) MAJGEN Michael Smith, AO (Retd) Dr Albert Palazzo Mrs Catherine McCullagh Dr Roger Lee RADM James Goldrick (Retd) Prof Michael Wesley AIRCDRE Anthony Forestier (Retd) Australian Army Journal Winter, Volume XI, No 1 CONTENTS CALL FOR PAPERS. -

Saunders Scholarship Background Parameters

The Captain Reg Saunders Memorial Scholarship Background The RSL established this tertiary level scholarship for drug and alcohol abuse studies in 1992 for students of an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander background. The Scholarship was named for Captain Reginald Walter Saunders MBE. In the development of the Scholarship, consultation with ATSIC revealed then, the urgent need for qualified substance abuse professionals among the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. As such, the Scholarship required an applicant to follow studies associated with the eradication of drug and alcohol abuse. Where student’s courses did not specifically contain subjects or units dealing with substance abuse, (e.g. nurses aid) the students must be able to provide scope for such studies in their elective subjects and/or field placements. For some years now the RSL administration of the granting of the scholarships has been established through the RSL National Trustees. The Scholarship One scholarship per year of $2000 to a student nominated by the University for agreement by the RSL National Trustees. The successful student must be of good academic standing and have the intention to use their skills or profession for the benefit of the aboriginal community. While a need for the eradication of drug and alcohol abuse remains important in applying the scholarship money, the grants may be used for leadership and personal development of recipients such that on their placement back in their communities they will be better equipped generally to provide a positive example and to advise on and assist in substance abuse among their other professional skills. Half yearly progress reports are required. -

Greek-Australian Alliance 1899

GREEK-AUSTRALIAN ALLIANCE 1899 - 2016 100th Anniversary Macedonian Front 75th Anniversary Battles of Greece and Crete COURAGE SACRIFICE MATESHIP PHILOTIMO 1899 -1902 – Greek Australians Frank Manusu (above), Constantine Alexander, Thomas Haraknoss, Elias Lukas and George Challis served with the colonial forces in the South African Boer War. 1912 - 1913 – Australian volunteers served in the Royal Hellenic Forces in the Balkans Wars. At the outbreak of the Second Balkan War in 1913, John Thomas Woods of the St John Ambulance volunteered for service with the Red Cross, assisting the Greek Medical Corps at Thessaloniki, a service for which he was recognised with a Greek medal by King Constantine of Greece. 1914 - 1918 – Approximately 90 Greek Australians served on Gallipoli and the Western Front. Some were born in Athens, Crete, Castellorizo, Kythera, Ithaca, Peloponnesus, Samos, and Cephalonia, Lefkada and Cyprus and others in Australia. They were joined by Greek Australian nurses, including Cleopatra Johnson (Ioanou), daughter of Antoni Ioanou, gold miner of Moonan Brook, NSW. One of 13 Greek Australian Gallipoli veterans, George Cretan (Bikouvarakis) was born in Kefalas, Crete in 1888 and migrated to Sydney in 1912. On the left in Crete, 1910 and middle in Sydney 1918 wearing his Gallipoli Campaign medals. Right, Greek Australian Western Front veteran Joseph Morris (Sifis Voyiatzis) of Cretan heritage. PAGE 2 1905-1923 -Sir Samuel Sydney Cohen was born on 11 March 1869 at Darlinghurst, Sydney, and was the eldest son of Jewish Australian parents George Judah Cohen and his wife Rebecca, daughter of L. W. Levy. He was a prominent and respected businessman in Newcastle and was appointed Vice-Consul General for Greece in Newcastle in March 1905. -

An Analysis of Australian Defense Policy from 1901 to Present

Security Nexus Research Abstract: Scholars generally consider AN ANALYSIS OF there to be three main eras in Australian Defense Policy: AUSTRALIAN DEFENSE POLICY The Imperial Defense era (1901-1945), Forward FROM 1901 TO PRESENT Defense era (1950-1975) and Defense of Australia era (1975-1997). These eras are By Major Jeremy “JB” Brown1 informed by world events, leaders and outside powers AUSTRALIAN DEFENSE POLICY INTRODUCTION that influence defense policy Australia’s eras of defense and contemporary policy can be on the continent. This summed up in Clausewitzian fashion that the nature of Australia’s analytical analysis examines defense policy has remained the same over time while the characters each major conceptual (prime ministers and defense ministers) are the only thing that has approach and themes changed. Since federation, Australian officials have been at odds as to defining defense policy the type of defense force Australia should maintain; whether it be throughout Australia’s developed for homeland defense or developed with the ability to history. Additionally, it conduct expeditionary operations. Historian David Horner shed some assesses how these themes light on this by saying ‘there had been tension between the inform and guide Australia’s Australianists, who wanted a militia that could not be deployed outside contemporary policy. Australia, and the Imperialists, who preferred a field force that could be Finally, the analysis provides deployed on imperial operations overseas.’ (Horner 2001) Out of this recommended insights on early defense identity crisis come a couple of enduring themes which are ways Australia can maintain the subject of this analysis. relevance as a competent middle-power within the The first theme is Australia having ‘a small population and little Indo-Pacific. -

Australian Memory and the Second World War

Journal of Military and Strategic VOLUME 14, ISSUE 1, FALL 2011 Studies The Second War in Every Respect: Australian memory and the Second World War Joan Beaumont The Second World War stands across the 20th century like a colossus. Its death toll, geographical spread, social dislocation and genocidal slaughter were unprecedented. It was literally a world war, devastating Europe, China and Japan, triggering massive movements of population, and unleashing forces of nationalism in Asia and Africa that presaged the end of European colonialism. The international order was changed irrevocably, most notably in the rise of the two superpowers and the decline of Great Britain. For Australia too, though the loss of life in the conflict was comparatively small, the war had a profound impact. The white population faced for the first time the threat of invasion, with Australian territory being bombed from the air and sea in 1942.1 The economy and society were mobilized to an unprecedented degree, with 993,000 men and women, of a population of nearly seven million, serving in the military forces. Nearly 40,000 of these were killed in action, died of wounds or died while prisoners of war.2 Gender roles, family life and social mores were changed with the mobilization of women into the industrial workforce and the friendly invasion of possibly a million 1 The heaviest raid was on the northern city of Darwin on 19 February 1942. Other towns in the north of Western Australia and Queensland were bombed across 1942; while on 31 May 1942 three Japanese midget submarines entered Sydney Harbour and shelled the suburbs.