The Iron Horse (Cometh the Railway)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cefn Viaduct.Pdf

The Cefn Viaduct Cefn Mawr Viaduct The Chester and Shrewsbury railway runs at the eastern end of the Vale of Llangollen, beyond the parish boundary, passing through Cefn Mawr on route from Chester to Shrewsbury. It is carried over the River Dee by a stupendous viaduct, half a mile down stream from the Pontcysyllte Aqueduct. It measures one thousand five hundred and eight feet in length, and stands one hundred and forty-seven feet above the level of the river. The structure is supported by nineteen arches with sixty foot spans. In 1845 rival schemes were put forward for railway lines to join Chester with Shrewsbury. Promoters of the plan to link Shrewsbury to Chester via Ruabon had to work quickly to get their scheme moving. Instructions for the notices and plans were only given on the 7th November and they had to be deposited with the clerk of Peace by the 30th November 1845. Hostility from objecting landowners meant that Robertson had to survey the land by night. One irate squire expressed a wish that someone would 'throw Robertson and his theodolite into the canal'. Henry Robertson told a Parliamentary Committee of the advantage of providing a railway line that would open up coalfields of Ruabon and Wrexham to markets at Chester, Birkenhead and Liverpool in the north and to Shrewsbury and other Shropshire towns on the south side. The Parliamentary Committee agreed with him and the bill received Royal Assent on 30th June 1845. The Shrewsbury and Chester Railway Company made good progress with construction work and the line to Ruabon from the north was opened in November 1846. -

Special Symposium Edition the Ground Beneath Our Feet: 200 Years of Geology in the Marches

NEWSLETTER August 2007 Special Symposium Edition The ground beneath our feet: 200 years of geology in the Marches A Symposium to be held on Thursday 13th September 2007 at Ludlow Assembly Rooms Hosted by the Shropshire Geological Society in association with the West Midlands Regional Group of the Geological Society of London To celebrate a number of anniversaries of significance to the geology of the Marches: the 200th anniversary of the Geological Society of London the 175th anniversary of Murchison's epic visit to the area that led to publication of The Silurian System. the 150th anniversary of the Geologists' Association The Norton Gallery in Ludlow Museum, Castle Square, includes a display of material relating to Murchison's visits to the area in the 1830s. Other Shropshire Geological Society news on pages 22-24 1 Contents Some Words of Welcome . 3 Symposium Programme . 4 Abstracts and Biographical Details Welcome Address: Prof Michael Rosenbaum . .6 Marches Geology for All: Dr Peter Toghill . .7 Local character shaped by landscapes: Dr David Lloyd MBE . .9 From the Ground, Up: Andrew Jenkinson . .10 Palaeogeography of the Lower Palaeozoic: Dr Robin Cocks OBE . .10 The Silurian “Herefordshire Konservat-Largerstatte”: Prof David Siveter . .11 Geology in the Community:Harriett Baldwin and Philip Dunne MP . .13 Geological pioneers in the Marches: Prof Hugh Torrens . .14 Challenges for the geoscientist: Prof Rod Stevens . .15 Reflection on the life of Dr Peter Cross . .15 The Ice Age legacy in North Shropshire: David Pannett . .16 The Ice Age in the Marches: Herefordshire: Dr Andrew Richards . .17 Future avenues of research in the Welsh Borderland: Prof John Dewey FRS . -

Handbook to Cardiff and the Neighborhood (With Map)

HANDBOOK British Asscciation CARUTFF1920. BRITISH ASSOCIATION CARDIFF MEETING, 1920. Handbook to Cardiff AND THE NEIGHBOURHOOD (WITH MAP). Prepared by various Authors for the Publication Sub-Committee, and edited by HOWARD M. HALLETT. F.E.S. CARDIFF. MCMXX. PREFACE. This Handbook has been prepared under the direction of the Publications Sub-Committee, and edited by Mr. H. M. Hallett. They desire me as Chairman to place on record their thanks to the various authors who have supplied articles. It is a matter for regret that the state of Mr. Ward's health did not permit him to prepare an account of the Roman antiquities. D. R. Paterson. Cardiff, August, 1920. — ....,.., CONTENTS. PAGE Preface Prehistoric Remains in Cardiff and Neiglibourhood (John Ward) . 1 The Lordship of Glamorgan (J. S. Corbett) . 22 Local Place-Names (H. J. Randall) . 54 Cardiff and its Municipal Government (J. L. Wheatley) . 63 The Public Buildings of Cardiff (W. S. Purchox and Harry Farr) . 73 Education in Cardiff (H. M. Thompson) . 86 The Cardiff Public Liljrary (Harry Farr) . 104 The History of iNIuseums in Cardiff I.—The Museum as a Municipal Institution (John Ward) . 112 II. —The Museum as a National Institution (A. H. Lee) 119 The Railways of the Cardiff District (Tho^. H. Walker) 125 The Docks of the District (W. J. Holloway) . 143 Shipping (R. O. Sanderson) . 155 Mining Features of the South Wales Coalfield (Hugh Brajiwell) . 160 Coal Trade of South Wales (Finlay A. Gibson) . 169 Iron and Steel (David E. Roberts) . 176 Ship Repairing (T. Allan Johnson) . 182 Pateift Fuel Industry (Guy de G. -

Normanhurst and the Brassey Family

NORMANHURST AND THE BRASSEY FAMILY Today, perhaps, it is only architects whose names live with their engineered creations. Those who build bridges, roads and railways are hidden within the corporations responsible, but in the nineteenth century they could be national heroes. They could certainly amass considerable wealth, even if they faced remarkable risks in obtaining it. One of the – perhaps the greatest – was the first Thomas Brassey. Brassey was probably the most successful of the contractors, was called a European power, through whose accounts more flowed in a year than through the treasuries of a dozen duchies and principalities, but he was such a power only with his navvies. Brassey's work took him and his railway business across the world, from France to Spain, Italy, Norway, what is now Poland, the Crimea, Canada, Australia, India and South America, quite apart from major works in the UK. His non-railway work was also impressive: docks, factories and part of Bazalgette's colossal sewerage and embankment project in London that gave us, among more important things, the Victoria and Albert Embankments, new streets and to some extent the District and Circle Lines. By 1870 he had built one mile in every twenty across the world, and in every inhabited continent. When he died at the (Royal) Victoria Hotel at St Leonards on 8 December 1870 Brassey left close to £3,200,000, a quite enormous sum that in today's terms would probably have been over a thousand million. He had been through some serious scares when his contracts had not yielded what he had expected, and in the bank crisis of 1866, but he had survived Thomas Brassey, contractor (or probably it his son Thomas) to build the colossal country house of Normanhurst Court in the parish of Catsfield. -

Railways List

A guide and list to a collection of Historic Railway Documents www.railarchive.org.uk to e mail click here December 2017 1 Since July 1971, this private collection of printed railway documents from pre grouping and pre nationalisation railway companies based in the UK; has sought to expand it‟s collection with the aim of obtaining a printed sample from each independent railway company which operated (or obtained it‟s act of parliament and started construction). There were over 1,500 such companies and to date the Rail Archive has sourced samples from over 800 of these companies. Early in 2001 the collection needed to be assessed for insurance purposes to identify a suitable premium. The premium cost was significant enough to warrant a more secure and sustainable future for the collection. In 2002 The Rail Archive was set up with the following objectives: secure an on-going future for the collection in a public institution reduce the insurance premium continue to add to the collection add a private collection of railway photographs from 1970‟s onwards provide a public access facility promote the collection ensure that the collection remains together in perpetuity where practical ensure that sufficient finances were in place to achieve to above objectives The archive is now retained by The Bodleian Library in Oxford to deliver the above objectives. This guide which gives details of paperwork in the collection and a list of railway companies from which material is wanted. The aim is to collect an item of printed paperwork from each UK railway company ever opened. -

![TV/Series, 9 | 2016, « Guerres En Séries (I) » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 01 Mars 2016, Consulté Le 18 Mai 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1578/tv-series-9-2016-%C2%AB-guerres-en-s%C3%A9ries-i-%C2%BB-en-ligne-mis-en-ligne-le-01-mars-2016-consult%C3%A9-le-18-mai-2021-381578.webp)

TV/Series, 9 | 2016, « Guerres En Séries (I) » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 01 Mars 2016, Consulté Le 18 Mai 2021

TV/Series 9 | 2016 Guerres en séries (I) Séries et guerre contre la terreur TV series and war on terror Marjolaine Boutet (dir.) Édition électronique URL : https://journals.openedition.org/tvseries/617 DOI : 10.4000/tvseries.617 ISSN : 2266-0909 Éditeur GRIC - Groupe de recherche Identités et Cultures Référence électronique Marjolaine Boutet (dir.), TV/Series, 9 | 2016, « Guerres en séries (I) » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 01 mars 2016, consulté le 18 mai 2021. URL : https://journals.openedition.org/tvseries/617 ; DOI : https:// doi.org/10.4000/tvseries.617 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 18 mai 2021. TV/Series est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. 1 Ce numéro explore de façon transdisciplinaire comment les séries américaines ont représenté les multiples aspects de la lutte contre le terrorisme et ses conséquences militaires, politiques, morales et sociales depuis le 11 septembre 2001. TV/Series, 9 | 2016 2 SOMMAIRE Préface. Les séries télévisées américaines et la guerre contre la terreur Marjolaine Boutet Détours visuels et narratifs Conflits, filtres et stratégies d’évitement : la représentation du 11 septembre et de ses conséquences dans deux séries d’Aaron Sorkin, The West Wing (NBC, 1999-2006) et The Newsroom (HBO, 2012-2014) Vanessa Loubet-Poëtte « Tu n’as rien vu [en Irak] » : Logistique de l’aperception dans Generation Kill Sébastien Lefait Between Unsanitized Depiction and ‘Sensory Overload’: The Deliberate Ambiguities of Generation Kill (HBO, 2008) Monica Michlin Les maux de la guerre à travers les mots du pilote Alex dans la série In Treatment (HBO, 2008-2010) Sarah Hatchuel 24 heures chrono et Homeland : séries emblématiques et ambigües 24 heures chrono : enfermement spatio-temporel, nœud d’intrigues, piège idéologique ? Monica Michlin Contre le split-screen. -

Cardiff 19Th Century Gameboard Instructions

Cardiff 19th Century Timeline Game education resource This resource aims to: • engage pupils in local history • stimulate class discussion • focus an investigation into changes to people’s daily lives in Cardiff and south east Wales during the nineteenth century. Introduction Playing the Cardiff C19th timeline game will raise pupil awareness of historical figures, buildings, transport and events in the locality. After playing the game, pupils can discuss which of the ‘facts’ they found interesting, and which they would like to explore and research further. This resource contains a series of factsheets with further information to accompany each game board ‘fact’, which also provide information about sources of more detailed information related to the topic. For every ‘fact’ in the game, pupils could explore: People – Historic figures and ordinary population Buildings – Public and private buildings in the Cardiff locality Transport – Roads, canals, railways, docks Links to Castell Coch – every piece of information in the game is linked to Castell Coch in some way – pupils could investigate those links and what they tell us about changes to people’s daily lives in the nineteenth century. Curriculum Links KS2 Literacy Framework – oracy across the curriculum – developing and presenting information and ideas – collaboration and discussion KS2 History – skills – chronological awareness – Pupils should be given opportunities to use timelines to sequence events. KS2 History – skills – historical knowledge and understanding – Pupils should be given -

Ludlow Bus Guide Contents

Buses Shropshire Ludlow Area Bus Guide Including: Ludlow, Bitterley, Brimfield and Woofferton. As of 23rd February 2015 RECENT CHANGES: 722 - Timetable revised to serve Tollgate Road Buses Shropshire Page !1 Ludlow Bus Guide Contents 2L/2S Ludlow - Clee Hill - Cleobury Mortimer - Bewdley - Kidderminster Rotala Diamond Page 3 141 Ludlow - Middleton - Wheathill - Ditton Priors - Bridgnorth R&B Travel Page 4 143 Ludlow - Bitterley - Wheathill - Stottesdon R&B Travel Page 4 155 Ludlow - Diddlebury - Culmington - Cardington Caradoc Coaches Page 5 435 Ludlow - Wistanstow - The Strettons - Dorrington - Shrewsbury Minsterley Motors Pages 6/7 488 Woofferton - Brimfield - Middleton - Leominster Yeomans Lugg Valley Travel Page 8 490 Ludlow - Orleton - Leominster Yeomans Lugg Valley Travel Page 8 701 Ludlow - Sandpits Area Minsterley Motors Page 9 711 Ludlow - Ticklerton - Soudley Boultons Of Shropshire Page 10 715 Ludlow - Great Sutton - Bouldon Caradoc Coaches Page 10 716 Ludlow - Bouldon - Great Sutton Caradoc Coaches Page 10 722 Ludlow - Rocksgreen - Park & Ride - Steventon - Ludlow Minsterley Motors Page 11 723/724 Ludlow - Caynham - Farden - Clee Hill - Coreley R&B Travel/Craven Arms Coaches Page 12 731 Ludlow - Ashford Carbonell - Brimfield - Tenbury Yarranton Brothers Page 13 738/740 Ludlow - Leintwardine - Bucknell - Knighton Arriva Shrewsbury Buses Page 14 745 Ludlow - Craven Arms - Bishops Castle - Pontesbury Minsterley Motors/M&J Travel Page 15 791 Middleton - Snitton - Farden - Bitterley R&B Travel Page 16 X11 Llandridnod - Builth Wells - Knighton - Ludlow Roy Browns Page 17 Ludlow Network Map Page 18 Buses Shropshire Page !2 Ludlow Bus Guide 2L/2S Ludlow - Kidderminster via Cleobury and Bewdley Timetable commences 15th December 2014 :: Rotala Diamond Bus :: Monday to Saturday (excluding bank holidays) Service No: 2S 2L 2L 2L 2L 2L 2L 2L 2L 2L Notes: Sch SHS Ludlow, Compasses Inn . -

Development Management Report

Committee and date Item South Planning Committee 7 3 December 2013 Public Development Management Report Responsible Officer: Tim Rogers email: [email protected] Tel: 01743 258773 Fax: 01743 252619 Summary of Application Application Number: 13/04014/MAW Parish : Woofferton Proposal : 500kW Anaerobic Digester (AD) Plant and Associated Infrastructure on Land off Park Lane, Woofferton Site Address : Land off Park Lane, Woofferton Applicant : Ludlow Bioenergy Ltd Case Officer : Graham French email : [email protected] Recommendation:- Grant Permission subject to the conditions and legal obligation set out in Appendix 1. Contact: Tim Rogers (01743) 258773 Page 1 of 40 Land off Park Lane, South Planning Committee – 3 December 2013 Woofferton Statement of Compliance with Article 31 of the Town and Country Development Management Procedure Order 2012 The authority worked with the applicant in a positive and pro-active manner in order to seek solutions to problems arising in the processing of the planning application. This is in accordance with the advice of the Governments Chief Planning Officer to work with applicants in the context of the NPPF towards positive outcomes. The applicant sought and was provided with formal pre-application advice by the authority. Further information has since been submitted on noise, odour and vehicle movements in response to comments received during the planning consultation process. The submitted scheme, has allowed the identified planning issues raised by the proposals to be satisfactorily addressed, subject to the recommended planning conditions and legal agreement. REPORT 1.0 THE PROPOSAL 1.1 The applicant, Ludlow Bioenergy Ltd is proposing to establish an agricultural anaerobic digestion facility at the site which would use feedstock from a nearby poultry unit and from surrounding farmland. -

FINAL MAP FRONT.Indd 1 13/02/2014 10:43:14

Coniston Bowness-on- Morton-on-Swale Windermere Coniston Water Kendal Lake R Windermere I V N E E Maunby R V Kirkby E Sedgwick Misperton A C L B C D E F R Newby Bridge G H R Thirsk COSTA A VE Crooklands K RI L BECK E A N COD A Yedingham Ryton C BECK R Topcliffe IV R E Ulverston 14m 8L R R R E IV Dalton YE T E S R S ULVERSTON A 8 W C A Malton CANAL Tewitfield Ripon LE N R I T Norton A P 1 N O L E N Helperby W C 17m 6L R Carnforth 6h Navigation works E D unfinished Bolton-le-Sands Myton-on-Swale R Kirkham Sheriff E 12m 0L 4h Boroughbridge V Hutton I R R IV Howsham E S Navigable waterway: broad, narrow R Linton S 11½m 8L U O R F DRIF Waterway under restoration Lancaster E Strensall FIEL 11m 0L 2½h R D Driffield NA 2 2 E V’N Derelict waterway 5m 0L V 1½h I Earswick 5m 4L Restored as Gargrave Skelton R Brigham Unimproved river historically used for navigation, or drain R single lock 2 4 IV Right of Glasson E navigation Stamford Bridge W Proposed new waterway Galgate L R e 6 E O disputed st B North L Bank Newton ED U eck Frodingham 6 A Skipton S S 10½m 1L Navigable lock; site of derelict lock (where known) E N & 3h 16m 15L 2 11m 2L 3h C L 8h IV Fulford Navigable tunnel; site of derelict tunnel A ER Aik S Greenberfield e 8m 0L Silsden P Beck Thrupp Flight of locks; inclined plane or boat lift; fixed sluice or weir T York POCKLINGTON 3 O Lockington 2½h E OL 10m 1L 3h Sutton CANAL R Pocklington Barnoldswick CA Leven Miles, locks and cruising hours between markers Garstang N C Arram 7m 8L A Tadcaster Navigation Naburn 3 LEVEN C On rivers: 4mph, -

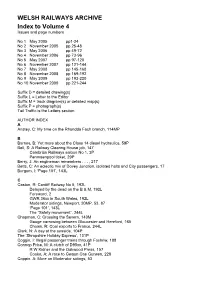

WELSH RAILWAYS ARCHIVE Index to Volume 4 Issues and Page Numbers

WELSH RAILWAYS ARCHIVE Index to Volume 4 Issues and page numbers No 1 May 2005 pp1-24 No 2 November 2005 pp 25-48 No 3 May 2006 pp 49-72 No 4 November 2006 pp 73-96 No 5 May 2007 pp 97-120 No 6 November 2007 pp 121-144 No 7 May 2008 pp 145-168 No 8 November 2008 pp 169-192 No 9 May 2009 pp 193-220 No 10 November 2009 pp 221-244 Suffix D = detailed drawing(s) Suffix L = Letter to the Editor Suffix M = track diagram(s) or detailed map(s) Suffix P = photograph(s) Tail Traffic is the Letters section AUTHOR INDEX A Anstey, C: My time on the Rhondda Fach branch, 114MP B Barnes, B: Yet more about the Class 14 diesel hydraulics, 59P Bell, S: A Railway Clearing House job, 147 Cambrian Railways saloon No 1, 3P Penmaenpool ticket, 29P Berry, J: An engineman remembers . , 217 Betts, C: An eclectic mix of Dovey Junction, isolated halts and City passengers, 17 Burgum, I: ‘Page 101’, 143L C Caston, R: Cardiff Railway No 5, 192L Delayed by the dead on the B & M, 192L Foreword, 2 GWR 36xx in South Wales, 192L Moderator sidings, Newport, 20MP, 53, 87 ‘Page 101’, 143L The “Safety movement”, 244L Chapman, C: Crossing the Severn, 140M Gauge narrowing between Gloucester and Hereford, 165 Chown, R: Coal exports to France, 244L Clark, N: A day at the seaside, 104P The ‘Shropshire Holiday Express’, 131P Coggin, I: Illegal passenger trains through Fochriw, 188 Connop Price, M: A clutch of D95xx, 41P R W Kidner and the Oakwood Press, 157 Cooke, A: A race to Gwaun Cae Gurwen, 228 Coppin, A: More on Moderator sidings, 53 D David, J: Getting a handle on private owner -

Blaenavon Management Plan

Nomination of the BLAENAVON INDUSTRIAL LANDSCAPE for inclusion in the WORLD HERITAGE LIST WORLD HERITAGE SITE MANAGEMENT PLAN Management Plan for the Nominated World Heritage Site of BLAENAVON INDUSTRIAL LANDSCAPE Version 1.2 October 1999 Prepared by THE BLAENAVON PARTNERSHIP TORFAEN BWRDEISTREF COUNTY SIROL BOROUGH TORFAEN Torfaen County Borough Council British Waterways Wales Tourist Royal Commission on the Ancient Blaenau Gwent County Monmouthshire Countryside Council CADW Board Board & Historical Monuments of Wales Borough Council County Council for Wales AMGUEDDFEYDD AC ORIELAU CENEDLAETHOL CYMRU NATIONAL MUSEUMS & GALLERIES OF WALES National Brecon Beacons Welsh Development Blaenavon National Museums & Galleries of Wales Trust National Park Agency Town Council For Further Information Contact John Rodger Blaenavon Co-ordinating Officer Tel: +44(0)1633 648317 c/o Development Department Fax:+44(0)1633 648088 Torfaen County Borough Council County Hall, CWMBRAN NP44 2WN e-mail:[email protected] Nomination of the BLAENAVON INDUSTRIAL LANDSCAPE for the inclusion in the WORLD HERITAGE LIST We as representatives of the Blaenavon Partnership append our signatures as confirmation of our support for the Blaenavon Industrial Landscape Management Plan TORFAEN BWRDEISTREF COUNTY SIROL BOROUGH TORFAEN Torfaen County Borough Council Monmouthshire Blaenau Gwent County County Council Borough Council Brecon Beacons Blaenavon National Park Town Council Royal Commission on the Ancient CADW & Historical Monuments of Wales AMGUEDDFEYDD AC ORIELAU