Blaenavon Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gwent Record Office

GB0218 D3544 Gwent Record Office This catalogue was digitised by The National Archives as part of the National Register of Archives digitisation project NRA 42931 The National Archives GWENT RECORD OFFICE D3544 Records of Devauden Community Council County Hall, Cwmbran. ABS/JR February 2000 Devauden Parish Council was formed in 1935. It became a community council in 1974. MINUTES D 3544. 1 MINUTE BOOK of Newchurch East 1929- 1949 Parish Council (and of Devauden Parish Council from 1935) D 3544. 2 MINUTE BOOK 1953 - 1964 D 3544. 3 MINUTE BOOK 1964 - 1970 D 3544. 4 MINUTE BOOK 1970 - 1973 D 3544. 5 MINUTE BOOK 1973 - 1975 D 3544. 6 MINUTE BOOK 1975 - 1978 D 3544. 7 MINUTE BOOK 1978 - 1982 D 3544. 8 MINUTE BOOK 1982 - 1986 D3544. 9 MINUTE BOOK 1986 - 1990 D3544. 10 MINUTE BOOK 1990 - 1991 D 3544. 11 MINUTE BOOK 1992 D 3544. 12 MINUTE BOOK 1992 - 1994 FINANCE D 3544. 13 PARISH COUNCIL CONTRIBUTION ORDERS 1912 - 1946 D 3544. 14 EXPENSES BOOK of clerk 1936- 1972 D3544. 15 RECEIPT AND PAYMENT BOOK of 1944 - 1985 Devauden Parish Council D3544. 16 CORRESPONDENCE, BANK STATEMENTS 1946- 1963 AND CHEQUES from the Midland Bank D3544. 17 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 1949- 1961 D3544. 18 INVOICES AND RECEIPTS 1950- 1961 D 3544. 19 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS, CORRESPONDENCE 1959 - 1980 AND USED CHEQUES D 3544. 20 RECEIPTS, CORRESPONDENCE AND 1961 - 1969 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS D 3544. 21 PRECEPTS upon Chepstow U.D.C. and Monmouth 1961 - 1980 District Council for expenses D 3544. 22 BANK STATEMENTS, CORRESPONDENCE, 1966 - 1979 RECEIPTS AND NOTICE OF AUDIT D 3544. -

X24 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

X24 bus time schedule & line map X24 Blaenavon - Newport View In Website Mode The X24 bus line (Blaenavon - Newport) has 5 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Blaenavon: 6:22 AM - 8:20 PM (2) Cwmbran: 6:02 PM - 7:02 PM (3) Cwmbran: 6:00 PM - 9:15 PM (4) Newport: 6:00 AM - 8:15 PM (5) Varteg: 9:20 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest X24 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next X24 bus arriving. Direction: Blaenavon X24 bus Time Schedule 42 stops Blaenavon Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 9:15 AM - 6:00 PM Monday 6:22 AM - 8:20 PM Market Square 16, Newport Tuesday 6:22 AM - 8:20 PM Llanyravon Boating Lake, Llanyrafon Wednesday 6:22 AM - 8:20 PM Llanyravon Square, Llanyrafon Thursday 6:22 AM - 8:20 PM Llan-yr-avon Square, Llanyrafon Community Friday 6:22 AM - 8:20 PM Redbrook House, Southville Saturday 6:22 AM - 8:20 PM Llantarnam Grange, Cwmbran Bus Station E, Cwmbran Gwent Square, Cwmbran X24 bus Info Llantarnam Grange, Cwmbran Direction: Blaenavon Stops: 42 Trussel Road, Northville Trip Duration: 58 min St David's Road, Cwmbran Line Summary: Market Square 16, Newport, Llanyravon Boating Lake, Llanyrafon, Llanyravon Ebenezer, Northville Square, Llanyrafon, Redbrook House, Southville, Llantarnam Grange, Cwmbran, Bus Station E, Avondale Close, Pontrhydyrun Cwmbran, Llantarnam Grange, Cwmbran, Trussel Road, Northville, Ebenezer, Northville, Avondale Avondale Close, Cwmbran Close, Pontrhydyrun, Ashbridge, Pontrhydyrun, Parc Ashbridge, Pontrhydyrun Panteg, Pontrhydyrun, South Street, Sebastopol, -

Whitby Abbey, the DURHAM - YORK Church with Its Tombstones and Even the 3 HRS 30MINS Bats Flying Around the Many Churches

6 Days / 5 Nights Self-drive Itinerary LOSE YOURSELF Starting from Edinburgh, this 6 days, 5 nights itinerary is perfect for those who simply love nothing better than to jump in the car and hit the open road! From Scotland, you will wind your way down South, visiting York, Lincoln & Cambridge, before arriving Iconic Experiences in London. (not to be missed) SURPRISE YOURSELF You're coming to England (finally!) and you need to make sure you tick those all-important things off your Learn more about Britain's list. fascinating history, by uncovering more about it's Viking past & We'll show you a veritable 'Treasure Trove' of delights, University history. Find the Magna all to be uncovered in England's Historic cities - with an Carta in Lincoln Cathedral and keep ASA twist - and ensure you are always in the best place, an eye out for the Lincoln Imp! at the right time, for that Instagram-perfect moment Punt along the river in Cambridge, Visit the fascinating city of Durham, home to Durham Cathedral, a UNESCO World Heritage Site and on your final day explore the delights of the City of London. Enjoy driving through the North York Moors National Park Experience the history at Lincoln Cathedral and see the Magna Carta at Lincoln Castle top tip: DAY 1 Visit Durham Castle and University; join a tour which will be hosted by a student from Durham University. HIGHLIGHTS ALNWICK CASTLE Alnwick Castle is one of the most iconic castles in England. Home to the Duke of Northumberland's family, the Percys, for over 700 years, it has witnessed drama, intrigue, tragedy and romance. -

Newsletter 16

Number 16 March 2019 Price £6.00 Welcome to the 16th edition of the Welsh Stone Forum May 11th: C12th-C19th stonework of the lower Teifi Newsletter. Many thanks to everyone who contributed to Valley this edition of the Newsletter, to the 2018 field programme, Leader: Tim Palmer and the planning of the 2019 programme. Meet:Meet 11.00am, Llandygwydd. (SN 240 436), off the A484 between Newcastle Emlyn and Cardigan Subscriptions We will examine a variety of local and foreign stones, If you have not paid your subscription for 2019, please not all of which are understood. The first stop will be the forward payment to Andrew Haycock (andrew.haycock@ demolished church (with standing font) at the meeting museumwales.ac.uk). If you are able to do this via a bank point. We will then move to the Friends of Friendless transfer then this is very helpful. Churches church at Manordeifi (SN 229 432), assuming repairs following this winter’s flooding have been Data Protection completed. Lunch will be at St Dogmael’s cafe and Museum (SN 164 459), including a trip to a nearby farm to Last year we asked you to complete a form to update see the substantial collection of medieval stonework from the information that we hold about you. This is so we the mid C20th excavations which have not previously comply with data protection legislation (GDPR, General been on show. The final stop will be the C19th church Data Protection Regulations). If any of your details (e.g. with incorporated medieval doorway at Meline (SN 118 address or e-mail) have changed please contact us so we 387), a new Friends of Friendless Churches listing. -

915 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

915 bus time schedule & line map 915 Pontypool View In Website Mode The 915 bus line (Pontypool) has 3 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Pontypool: 3:29 PM (2) Trevethin: 7:29 AM - 3:10 PM (3) Trosnant: 7:36 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 915 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 915 bus arriving. Direction: Pontypool 915 bus Time Schedule 18 stops Pontypool Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 3:29 PM Shops, Trevethin Church Avenue, Trevethin Community Tuesday 3:29 PM Upland Drive, Trevethin Wednesday 3:29 PM West Hill Road, Trevethin Thursday 3:29 PM West Hill Road, Trevethin Community Friday 3:29 PM Beeches Road, Trevethin Saturday Not Operational Terminus, Trevethin Woodside Road, Trevethin Community Elmhurst Close, Trevethin 915 bus Info Central Drive, Trevethin Community Direction: Pontypool Stops: 18 Bythway Road, Trevethin Trip Duration: 16 min Line Summary: Shops, Trevethin, Upland Drive, Shops, Trevethin Trevethin, West Hill Road, Trevethin, Beeches Road, Church Avenue, Trevethin Community Trevethin, Terminus, Trevethin, Elmhurst Close, Trevethin, Bythway Road, Trevethin, Shops, Ysgol Gyfun Gwynllyw, Trevethin Trevethin, Ysgol Gyfun Gwynllyw, Trevethin, Ridgeway, Trevethin, Mount Road, Trevethin, School, Ridgeway, Trevethin Penygarn, James Street, Penygarn, Park Crescent, Ridgeway, Trevethin Community Penygarn, Park Gardens, Penygarn, Town Bridge, Pontypool, Park Road, Pontypool, Crane Street Loop, Mount Road, Trevethin Pontypool School, Penygarn James -

The Blaenavon Ironmasters

THE BLAENAVON IRONMASTERS The industrial revolution would never have occurred if it were not for the risks and innovation of entrepreneurs. In south Wales, during the late eighteenth century, ironmasters set up a string of new ironworks, making the region the most important iron-producing region in the world. The labouring classes undeniably played a hugely significant role in the industrialisation process but it was the capital and experience of businessmen that made the industrial revolution a success. This article examines the history of the Blaenavon ironmasters and how they used their experience and their influence to create the town of Blaenavon. The Experience of the Blaenavon Ironmasters The leases for the area of Blaenavon, known as ‘Lord Abergavenny’s Hills’, were not renewed during the 1780s. The West Midlands industrialist, Thomas Hill (1736-1824), and his partners, Thomas Hopkins (d.1793) and Benjamin Pratt (1742-1794), seized the opportunity to invest in the Blaenavon site, which they knew was rich in mineral resources. The businessmen invested some £40,000 into the ironworks project and erected three blast furnaces. It was an incredibly risky venture but the three men were confident that the enterprise would be a large-scale success and that their investment would provide considerable returns. The experience that all three men had acquired in iron-making, business and banking, proved invaluable in numerous ways. Family Background Thomas Hill, the leading partner, came from a very wealthy industrial background. He was a successful Worcestershire banker and ran Wollaston slitting mill. Hill had also inherited a considerable fortune from his father, Waldron Hill (1706-88), and his uncle, Thomas Hill (1711-82), who were successful glassmakers at Coalbournhill, Stourbridge. -

Cwmafon Heritage Trail Walk Leaflet

reaching Glebeland Farm, go through a gate. Cross the field diagonally right, to reach another gate. Scramble up the Cwmafon steep bank on the other side to reach a path which swings 3hr around to the left, giving a less steep climb up the incline. WALK Cwmafon Heritage Just beyond the wooden fences and Victorian stone embankment walls you reach the level of another old Difficulty of walk - 2 (easy) railway. This railway is described on OS maps as a ‘Mineral Heritage Trail Railway’, and was opened in 1878. The whole area was once a maze of rail and tramways, serving the various mines and other egin at Capel Newydd viewpoint parking area and industrial works. Today these old railway lines are used for the Trail Bpicnic site, on Llanover Road about 1.5 miles outside Torfaen Leisure Route (National Cycle Network Route 46), Blaenavon. which runs the length of the Borough, for walkers, cyclists and Torfaen South East Wales A non-conformist chapel was built here around 1750 by two horse-riders to use and enjoy. Turn left and follow the cycle wealthy ladies of Blaenafon. An iron cross is all that remains of way for a mile or more. Look out for reminders of the Victorian the chapel, but the site is still known locally and marked on maps golden age of railway architecture in the bridges, embankment as Capel Newydd. This chapel once served the valley around Blaenavon as the chapel of ease for Llanofer Church. In 1860, it was abandoned and its stone was quietly robbed to repair other buildings in the area. -

Mondays to Saturdays Stagecoach in South Wales

Stagecoach in South Wales Days of Operation Mondays to Saturdays Commencing 26th October 2020 Service Number X24 Service Description Blaenavon - Newport Service No. X24 X24 X24 X24 X24 X24 X24 X24 X24 X24 X24 X24 X24 X24 X24 X24 X24 X24 Newport City Bus Stn 16 - - 0710 0722 0734 0746 0758 then 10 22 34 46 58 Until 1310 1322 1334 1346 1358 1410 Llanyravon Square - - 0719 0731 0743 0755 0807 at 19 31 43 55 07 1319 1331 1343 1355 1407 1419 Cwmbran Bus Stn Std E - - 0723 0735 0747 0759 0811 these 23 35 47 59 11 1323 1335 1347 1359 1411 1423 Cwmbran Bus Stn Std E 0628 0652 0728 0740 0752 0804 0816 times 28 40 52 04 16 1328 1340 1352 1404 1416 1428 Pontymoile Stafford Road Top 0637 0701 0737 0749 0801 0813 0825 each 37 49 01 13 25 1337 1349 1401 1413 1425 1437 Pontypool Town Hall Std 4 0643 0707 0743 0755 0807 0819 0831 hour 43 55 07 19 31 1343 1355 1407 1419 1431 1443 Pontypool Town Hall Std 4 0644 0708 0744 0756 0808 0820 0832 44 56 08 20 32 1344 1356 1408 1420 1432 1444 St Albans School - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Abersychan Broad Street 0650 0714 0750 0802 0814 0826 0838 50 02 14 26 38 1350 1402 1414 1426 1438 1450 Varteg Hill Terminus 0656 0720 0756 0808 0820 0832 0844 56 08 20 32 44 1356 1408 1420 1432 1444 1456 Blaenavon Curwood 0702 0726 0802 - 0826 - - 02 - 26 - - 1402 - 1426 - - 1502 Blaenavon High Street - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Service No. -

TRADES. [:Monmol THSHIRE

~28 P[B TRADES. [:MONMOl THSHIRE. PuBLIC HousEs-continued. New inn, John James, Lower New Inn, Pontypool King'• Arms, John Summerfield, Trosnant st. Pontypool N~>w inn,Wm.H.Jeffreys, Llantilio-Pertholey,.A.berga"Venny King's Arms, Dl.Watkins, 57 King st. Blaenavon,Pontypl New inn, Albert W. Jones, Bedwellty, Cardiff King-'s Head, William Curtis, Old Market street, Usk New inn, David Charles Jonss, Abercarn, Newport King's Head, Thomas Green, Raglan, Newport New inn, Herbert Rowe Lawrence, Llangstone, Newpor\ King's Head, James Lewis, Redwick, Newport New inn, James Rosser, Skenfrith, Monmonth King's Head, Mrs. Jane Millard, Abertillery New inn, Alfred Sirrell, Llantilio-Crossenny, Abergvnny 'King's Head, Mrs. Caroline Noble, Cross Keys, Newport New inn, George Smith, Bishton, Newport King's Head, Mrs:.A.lice R. Powell, 6o Cross st.Abergvnny New Bridge, A. J. Featherstone, 51 Bridge st. Newport Xing's Head inn, Henry Rees, Castle street, Tredegar XPw Bridge End, Thomas John Stewart, Cwmtillery, King's Head, Allen Trother, Redbrook, Monmouth Abertillery King's Head, Wm. Wells, Station rd. Pontnewydd, Newp011 New Court, James Baker, Maryport street, Usk Xing's Head tap, Blackburn & Co. 203 Dock st. Newport N~>w Market inn, Thomas James Lloyd, 22 Lion stl't'et, 'Labour in Vain, Charles Jeffries, 39 High st. Pontypool Abergavenny Lamb inn, William Bevan, Penyrheol, Pontypool North Western, Charlec; A. Davies, Church st. Tredegar 'Lamb inn, Alfred Cleveland Erratt, Commercial street, North Western betel, G. Hambling,Brecon rd.Abergvnny Briery Hill, Ebbw Vale Oakfield inn, John Jones, Oakfield, Cwmbran, Newport "*Lamb, William Matthews, 25 Merthyr rd. -

The Newsletter of the Federation of Museums & Art Galleries Of

The newsletter of the Federation of Museums & Art Galleries of Wales April 2011 The 2010 Federation AGM, Llanberis In November each year the Federation holds its AGM in a prominent museum or gallery and alternates between North & South Wales. In 2010 the AGM was hosted by the National Slate Museum in Llanberis and the keynote speaker was the new Director General of Amgueddfa Cymru, David Anderson. The event took place in the museum’s Padarn Room, one of two available conference / education rooms. The Federation President, Rachael Rogers (Monmouthshire Museums Service) presented the Federation’s Annual Report for 2009/10 and the The Padarn Room, National Slate Honorary Treasurer, Susan Dalloe (Denbighshire Federation President, Rachael Rogers and keynote speaker, Museum, Llanvberis Director-General of NMW / AC, David Anderson, at the AGM Heritage Service) presented the annual accounts. Following election of Committee Members and other business, David Anderson then gave his talk to the Members. Having only been in his current post as Director General of Amgueddfa Cymru for six weeks, Mr Anderson not only talked of his career and museum experiences that led to his appointment but also asked the Federation Members for their contributions on the Welsh museum and gallery sector and relationships between the differing museums and the National Museum Wales. Following a delicious lunch served in the museum café, the afternoon was spent in a series of workshops with all Members contributing ideas for the Federation’s forthcoming Advocacy strategy and Members toolkit. The Advocacy issue is very important to the Federation especially in the current economic climate and so, particularly if you were unable to attend the AGM, the following article is to encourage your contribution: How Can You Develop an Advocacy Strategy? The Federation is well on its way to finalising an advocacy strategy for museums in Wales. -

Torfaen County Borough Council Local Development Plan Delivery Agreement Third Version

Torfaen County Borough Council Local Development Plan Delivery Agreement Third Version Approved January 2009 Further information can be obtained by contacting the following: Forward Planning Team Planning & Public Protection 3rd Floor County Hall Cwmbran NP44 2WN Telephone: 01633 648805 Fax: 01633 647328 Email: [email protected] Content Page Preface 3 Introduction 4 Purpose of this Delivery Agreement 4 The purpose of the Local Development Plan and context for its preparation 4 Format of the Local Development Plan 5 Supplementary Planning Guidance 5 Stages of the Delivery Agreement 5 Sustainability Appraisal and Strategic Environmental Appraisal 6 Independent Examination of Soundness 6 The Timetable 7 Key Stage Timetable 7 Definitive and Indicative Stages 7 Project Management 7 Managing Risk 7 Figure 2.1 - Stage Timetable for Local Development Plan Preparation 7 Figure 2.2 - Full Timetable for the preparation of the Torfaen LDP 8 The Community Involvement Scheme 11 Introduction 11 Aims of Community Involvement in Local Development Plan 11 Principles of Community Involvement 11 Process of Community Involvement 12 Consensus Building 13 Key stages in plan preparation giving opportunities for community 13 Involvement and consensus building Local Development Plan preparation and consultation 13 Council decision making structure 14 Monitoring and Review 15 Glossary of Terms 16 Appendices 20 Appendix A - Torfaen Local Development Plan Risk Assessment 21 Appendix B - Torfaen Citizen Engagement Toolkit 23 Appendix C - Local Planning Authority expectations -

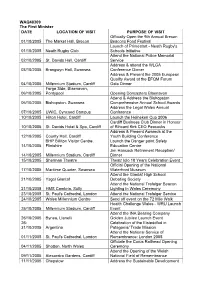

WAQ48309 the First Minister DATE LOCATION OF

WAQ48309 The First Minister DATE LOCATION OF VISIT PURPOSE OF VISIT Officially Open the 9th Annual Brecon 01/10/2005 The Market Hall, Brecon Beacons Food Festival Launch of Primestart - Neath Rugby's 01/10/2005 Neath Rugby Club Schools Initiative Attend the National Police Memorial 02/10/2005 St. Davids Hall, Cardiff Service Address & attend the WLGA 03/10/2005 Brangwyn Hall, Swansea Conference Dinner Address & Present the 2005 European Quality Award at the EFQM Forum 04/10/2005 Millennium Stadium, Cardiff Gala Dinner Forge Side, Blaenavon, 06/10/2005 Pontypool Opening Doncasters Blaenavon Attend & Address the Bishopston 06/10/2005 Bishopston, Swansea Comprehensive Annual School Awards Address the Legal Wales Annual 07/10/2005 UWIC, Cyncoed Campus Conference 10/10/2005 Hilton Hotel, Cardiff Launch the Heineken Cup 2006 Cardiff Business Club Dinner in Honour 10/10/2005 St. Davids Hotel & Spa, Cardiff of Rihcard Kirk CEO Peacocks Address & Present Awareds at the 12/10/2005 County Hall, Cardiff Youth Building Conference BHP Billiton Visitor Centre, Launch the Danger point Safety 14/10/2005 Flintshire Education Centre Jim Hancock Retirement Reception/ 14/10/2005 Millennium Stadium, Cardiff Dinner 15/10/2005 Sherman Theatre Theatr Iolo 18 Years Celebration Event Official Opening of the National 17/10/2005 Maritime Quarter, Swansea Waterfront Museum Attend the Glantaf High School 21/10/2005 Ysgol Glantaf Debating Society Attend the National Trafalgar Beacon 21/10/2005 HMS Cambria, Sully Lighting in Wales Ceremony 23/10/2005 St. Paul's Cathedral, London Attend the National Trafalgar Service 24/10/2005 Wales Millennium Centre Send off event on the 72 Mile Walk Health Challenge Wales - WRU Launch 25/10/2005 Millennium Stadium, Cardiff Event Attend the INA Bearing Company 26/10/2005 Bynea, Llanelli Golden Jubilee Launch Event 26- Celebration of the Eisteddfod in 31/10/2005 Argentina Patagonia/ Trade Mission Attend the National Service of 01/11/2005 St.