Defending Democracy Against Illiberal Challengers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Impact of Populist Radical Right Parties on National Immigration and Integration Policies in Europe an Analysis of Finland, Sweden, Denmark and the Netherlands

The impact of populist radical right parties on national immigration and integration policies in Europe An analysis of Finland, Sweden, Denmark and the Netherlands Author: Aniek van Beijsterveldt (461462ab) August 9, 2018 Supervisor: Prof. dr. M. Haverland MSc International Public Management and Policy Second reader: Dr. A.T. Zhelyazkova Erasmus School of Social and Behavioural Sciences Word count: 23,751 0 Erasmus University Rotterdam (EUR) The impact of populist radical right parties on national immigration and integration policies in Europe An analysis of Finland, Sweden, Denmark and the Netherlands Master thesis submitted to: Department of Public Administration, Erasmus School of Social and Behavioural Sciences, Erasmus University Rotterdam (EUR), in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of International Public Management and Policy (IMP) By Aniek van Beijsterveldt (461462ab) Supervisor and first reader: Prof. dr. M. Haverland Second reader: Dr. A.T. Zhelyazkova Word count: 23,751 Abstract Populist radical right parties have emerged as an electoral force in Europe over the last three decennia. This has raised concerns among citizens, politicians, journalists and academia. However, scholars disagree whether or not populist radical right parties are able to influence policies. This thesis therefore examines the direct influence of populist radical right parties on immigration and integration policies by comparing the output of 17 cabinets of varying composition in Finland, Sweden, Denmark and the Netherlands between 2009 and 2016. A policy index has been developed to measure legislative changes with regard to citizenship and denizenship, asylum, illegal residence, family reunion and integration. The index showed that centre-right cabinets supported by populist radical right parties scored on average highest on the NIIP index, which means they succeeded best in producing restrictive immigration and integration legislation. -

Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM UVM Honors College Senior Theses Undergraduate Theses 2018 Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany William Peter Fitz University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses Recommended Citation Fitz, William Peter, "Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany" (2018). UVM Honors College Senior Theses. 275. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses/275 This Honors College Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in UVM Honors College Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REACTIONARY POSTMODERNISM? NEOLIBERALISM, MULTICULTURALISM, THE INTERNET, AND THE IDEOLOGY OF THE NEW FAR RIGHT IN GERMANY A Thesis Presented by William Peter Fitz to The Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Bachelor of Arts In European Studies with Honors December 2018 Defense Date: December 4th, 2018 Thesis Committee: Alan E. Steinweis, Ph.D., Advisor Susanna Schrafstetter, Ph.D., Chairperson Adriana Borra, M.A. Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter One: Neoliberalism and Xenophobia 17 Chapter Two: Multiculturalism and Cultural Identity 52 Chapter Three: The Philosophy of the New Right 84 Chapter Four: The Internet and Meme Warfare 116 Conclusion 149 Bibliography 166 1 “Perhaps one will view the rise of the Alternative for Germany in the foreseeable future as inevitable, as a portent for major changes, one that is as necessary as it was predictable. -

The New Right

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1984 The New Right Elizabeth Julia Reiley College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Reiley, Elizabeth Julia, "The New Right" (1984). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625286. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-mnnb-at94 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE NEW RIGHT 'f A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Sociology The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Elizabeth Reiley 1984 This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Elizabeth Approved, May 1984 Edwin H . Rhyn< Satoshi Ito Dedicated to Pat Thanks, brother, for sharing your love, your life, and for making us laugh. We feel you with us still. Presente! iii. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................... v ABSTRACT.................................... vi INTRODUCTION ................................ s 1 CHAPTER I. THE NEW RIGHT . '............ 6 CHAPTER II. THE 1980 ELECTIONS . 52 CHAPTER III. THE PRO-FAMILY COALITION . 69 CHAPTER IV. THE NEW RIGHT: BEYOND 1980 95 CHAPTER V. CONCLUSION ............... 114 BIBLIOGRAPHY .................................. 130 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The writer wishes to express her appreciation to all the members of her committee for the time they gave to the reading and criticism of the manuscript, especially Dr. -

The Impact of the New Right on the Reagan Administration

LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS UNIVERSITY OF LONDON THE IMPACT OF THE NEW RIGHT ON THE REAGAN ADMINISTRATION: KIRKPATRICK & UNESCO AS. A TEST CASE BY Isaac Izy Kfir LONDON 1998 UMI Number: U148638 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U148638 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 2 ABSTRACT The aim of this research is to investigate whether the Reagan administration was influenced by ‘New Right’ ideas. Foreign policy issues were chosen as test cases because the presidency has more power in this area which is why it could promote an aggressive stance toward the United Nations and encourage withdrawal from UNESCO with little impunity. Chapter 1 deals with American society after 1945. It shows how the ground was set for the rise of Reagan and the New Right as America moved from a strong affinity with New Deal liberalism to a new form of conservatism, which the New Right and Reagan epitomised. Chapter 2 analyses the New Right as a coalition of three distinctive groups: anti-liberals, New Christian Right, and neoconservatives. -

PSCI 5113 / EURR 5113 Democracy in the European Union Mondays, 11:35 A.M

Carleton University Fall 2019 Department of Political Science Institute of European, Russian and Eurasian Studies PSCI 5113 / EURR 5113 Democracy in the European Union Mondays, 11:35 a.m. – 2:25 p.m. Please confirm location on Carleton Central Instructor: Professor Achim Hurrelmann Office: D687 Loeb Building Office Hours: Mondays, 3:00 p.m. – 4:00 p.m., and by appointment Phone: (613) 520-2600 ext. 2294 Email: [email protected] Twitter: @achimhurrelmann Course description: Over the past seventy years, European integration has made significant contributions to peace, economic prosperity and cultural exchange in Europe. By contrast, the effects of integration on the democratic quality of government have been more ambiguous. The European Union (EU) possesses more mechanisms of democratic input than any other international organization, most importantly the directly elected European Parliament (EP). At the same time, the EU’s political processes are often described as insufficiently democratic, and European integration is said to have undermined the quality of national democracy in the member states. Concerns about a “democratic deficit” of the EU have not only been an important topic of scholarly debate about European integration, but have also constituted a major argument of populist and Euroskeptic political mobilization, for instance in the “Brexit” referendum. This course approaches democracy in the EU from three angles. First, it reviews the EU’s democratic institutions and associated practices of citizen participation: How -

Wien Institute for Advanced Studies, Vienna

Institut für Höhere Studien (IHS), Wien Institute for Advanced Studies, Vienna Reihe Politikwissenschaft / Political Science Series No. 45 The End of the Third Wave and the Global Future of Democracy Larry Diamond 2 — Larry Diamond / The End of the Third Wave — I H S The End of the Third Wave and the Global Future of Democracy Larry Diamond Reihe Politikwissenschaft / Political Science Series No. 45 July 1997 Prof. Dr. Larry Diamond Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace Stanford University Stanford, California 94305-6010 USA e-mail: [email protected] and International Forum for Democratic Studies National Endowment for Democracy 1101 15th Street, NW, Suite 802 Washington, DC 20005 USA T 001/202/293-0300 F 001/202/293-0258 Institut für Höhere Studien (IHS), Wien Institute for Advanced Studies, Vienna 4 — Larry Diamond / The End of the Third Wave — I H S The Political Science Series is published by the Department of Political Science of the Austrian Institute for Advanced Studies (IHS) in Vienna. The series is meant to share work in progress in a timely way before formal publication. It includes papers by the Department’s teaching and research staff, visiting professors, students, visiting fellows, and invited participants in seminars, workshops, and conferences. As usual, authors bear full responsibility for the content of their contributions. All rights are reserved. Abstract The “Third Wave” of global democratization, which began in 1974, now appears to be drawing to a close. While the number of “electoral democracies” has tripled since 1974, the rate of increase has slowed every year since 1991 (when the number jumped by almost 20 percent) and is now near zero. -

THE RISE of COMPETITIVE AUTHORITARIANISM Steven Levitsky and Lucan A

Elections Without Democracy THE RISE OF COMPETITIVE AUTHORITARIANISM Steven Levitsky and Lucan A. Way Steven Levitsky is assistant professor of government and social studies at Harvard University. His Transforming Labor-Based Parties in Latin America is forthcoming from Cambridge University Press. Lucan A. Way is assistant professor of political science at Temple University and an academy scholar at the Academy for International and Area Studies at Harvard University. He is currently writing a book on the obstacles to authoritarian consolidation in the former Soviet Union. The post–Cold War world has been marked by the proliferation of hy- brid political regimes. In different ways, and to varying degrees, polities across much of Africa (Ghana, Kenya, Mozambique, Zambia, Zimbab- we), postcommunist Eurasia (Albania, Croatia, Russia, Serbia, Ukraine), Asia (Malaysia, Taiwan), and Latin America (Haiti, Mexico, Paraguay, Peru) combined democratic rules with authoritarian governance during the 1990s. Scholars often treated these regimes as incomplete or transi- tional forms of democracy. Yet in many cases these expectations (or hopes) proved overly optimistic. Particularly in Africa and the former Soviet Union, many regimes have either remained hybrid or moved in an authoritarian direction. It may therefore be time to stop thinking of these cases in terms of transitions to democracy and to begin thinking about the specific types of regimes they actually are. In recent years, many scholars have pointed to the importance of hybrid regimes. Indeed, recent academic writings have produced a vari- ety of labels for mixed cases, including not only “hybrid regime” but also “semidemocracy,” “virtual democracy,” “electoral democracy,” “pseudodemocracy,” “illiberal democracy,” “semi-authoritarianism,” “soft authoritarianism,” “electoral authoritarianism,” and Freedom House’s “Partly Free.”1 Yet much of this literature suffers from two important weaknesses. -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

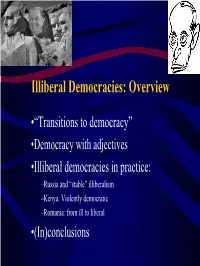

Illiberal Democracies: Overview

Illiberal Democracies: Overview •“Transitions to democracy” •Democracy with adjectives •Illiberal democracies in practice: –Russia and “stable” illiberalism –Kenya: Violently democratic –Romania: from ill to liberal •(In)conclusions “Transitions to democracy” • Transitions literature comes out of a reading of democratization in L.Am., ‘70s & ‘80s. • Mechanisms of transition (O’Donnell and Schmitter): – Splits appear in the authoritarian regime – Civil society and opposition develop – “Pacted” transitions Democracy with Adjectives • Problem: The transitions model is excessively teleological and just inaccurate • “Illiberal” meets “democracy” – What is democracy (again, and in brief)? – Why add “liberal”? – What in an illiberal democracy is “ill”? A Typology of Regimes Chart taken from Larry Diamond, “Thinking about Hybrid Regimes” Journal of Democracy 13: 2 (2002) How do “gray zone” regimes develop? • Thomas Carothers: Absence of pre-conditions to democracy, which is tied to… (Culturalist) • Fareed Zakaria: When baking a liberal democracy, liberalize then democratize (Institutionalist). • Michael McFaul: Domestic balance of power at the outset matters (path dependence). Where even, illiberalism may develop (Rationalist). Russia Poland Case studies: Russia • 1991-93: An even balance of power between Yeltsin and reformers feeds into political ambiguity…and illiberalism • After Sept 1993 - Yeltsin takes the advantage and uses it to shape Russia into a delegative democracy • The creation of President Putin • Putin and the “dictatorship of law” -

The Growth of the Radical Right in Nordic Countries: Observations from the Past 20 Years

THE GROWTH OF THE RADICAL RIGHT IN NORDIC COUNTRIES: OBSERVATIONS FROM THE PAST 20 YEARS By Anders Widfeldt TRANSATLANTIC COUNCIL ON MIGRATION THE GROWTH OF THE RADICAL RIGHT IN NORDIC COUNTRIES: Observations from the Past 20 Years By Anders Widfeldt June 2018 Acknowledgments This research was commissioned for the eighteenth plenary meeting of the Transatlantic Council on Migration, an initiative of the Migration Policy Institute (MPI), held in Stockholm in November 2017. The meeting’s theme was “The Future of Migration Policy in a Volatile Political Landscape,” and this report was one of several that informed the Council’s discussions. The Council is a unique deliberative body that examines vital policy issues and informs migration policymaking processes in North America and Europe. The Council’s work is generously supported by the following foundations and governments: the Open Society Foundations, Carnegie Corporation of New York, the Barrow Cadbury Trust, the Luso- American Development Foundation, the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, and the governments of Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden. For more on the Transatlantic Council on Migration, please visit: www.migrationpolicy.org/ transatlantic. © 2018 Migration Policy Institute. All Rights Reserved. Cover Design: April Siruno, MPI Layout: Sara Staedicke, MPI No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Migration Policy Institute. A full-text PDF of this document is available for free download from www.migrationpolicy.org. Information for reproducing excerpts from this report can be found at www.migrationpolicy.org/about/copyright-policy. -

PAPPA – Parties and Policies in Parliaments

PAPPA Parties and Policies in Parliament Version 1.0 (August 2004) Data description Martin Ejnar Hansen, Robert Klemmensen and Peter Kurrild-Klitgaard Political Science Publications No. 3/2004 Name: PAPPA: Parties and Policies in Parliaments, version 1.0 (August 2004) Authors: Martin Ejnar Hansen, Robert Klemmensen & Peter Kurrild- Klitgaard. Contents: All legislation passed in the Danish Folketing, 1945-2003. Availability: The dataset is at present not generally available to the public. Academics should please contact one of the authors with a request for data stating purpose and scope; it will then be determined whether or not the data can be released at present, or the requested results will be provided. Data will be made available on a website and through Dansk Data Arkiv (DDA) when the authors have finished their work with the data. Citation: Hansen, Martin Ejnar, Robert Klemmensen and Peter Kurrild- Klitgaard (2004): PAPPA: Parties and Policies in Parliaments, version 1.0, Odense: Department of Political Science and Public Management, University of Southern Denmark. Variables The total number of variables in the dataset is 186. The following variables have all been coded on the basis of the Folketingets Årbog (the parliamentary hansard) and (to a smaller degree) the parliamentary website (www.ft.dk): nr The number given in the parliamentary hansard (Folketingets Årbog), or (in recent years) the law number. sam The legislative session. eu Whether or not the particular piece of legislation was EU/EEC initiated. change Whether or not the particular piece of legislation was a change of already existing legislation. vedt Whether the particular piece of legislation was passed or not. -

DENMARK Dates of Elections: 8 September 1987 10 May 1988

DENMARK Dates of Elections: 8 September 1987 10 May 1988 Purpose of Elections 8 September 1987: Elections were held for all the seats in Parliament following premature dissolution of this body on 18 August 1987. Since general elections had previously been held in January 1984, they would not normally have been due until January 1988. 10 May 1988: Elections were held for all the seats in Parliament following premature dissolution of this body in April 1988. Characteristics of Parliament The unicameral Parliament of Denmark, the Folketing, is composed of 179 members elected for 4 years. Of this total, 2 are elected in the Faeroe Islands and 2 in Greenland. Electoral System The right to vote in a Folketing election is held by every Danish citizen of at least 18 years of age whose permanent residence is in Denmark, provided that he has not been declared insane. Electoral registers are compiled on the basis of the Central Register of Persons (com puterized) and revised continuously. Voting is not compulsory. Any qualified elector is eligible for membership of Parliament unless he has been convic ted "of an act which in the eyes of the public makes him unworthy of being a member of the Folketing". Any elector can contest an election if his nomination is supported by at least 25 electors of his constituency. No monetary deposit is required. Each candidate must declare whether he will stand for a certain party or as an independent. For electoral purposes, metropolitan Denmark (excluding Greenland and the Faeroe Islands) is divided into three areas - Greater Copenhagen, Jutland and the Islands.