David Lombardi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Government of NCT of Delhi

th 5 Delhi International Arts Festival Indian Council For 31st Oct.-15th Nov. 2011 Cultural Relations Prasiddha Forum for Art Beyond Borders FOUNDATION Government of NCT of Delhi nwjn'kZu LkR;e~ f'koe~ lqUnje~ diaf.buzzintown.com “ARTS” is simultaneously one of the most exciting and least understood of terminologies in India. ‘The Arts” in India face unique challenges. From classical to contemporary dance, classical to fusion to contemporary music, classical to contemporary paintings, sculpture, photography, puppetry, the arts are in a transformational stage in India. Most of these art forms are ephemeral. Because they are linguistic and region–specific (classical dances of India for example), and often non-notated, they do not enjoy the same advantages of being written down, stored and transferred that literature and film enjoy. Classical Arts also has an undeserved reputation as being difficult to understand. Statistics informs Stake-holders that its audiences are small, despite the passion and loyalty of the artistes themselves. Indian arts media is facing challenges of its own with new writers struggling to understand or cover the “Arts” with any depth and sensitivity. Gone are traditional Sabha Organisers who nurtured the Art Forms with diligence and continuity. The new Organisers want a little bit of Bollywood in everything they touch. As also the new patrons of Culture –the Corporates. They want a lot of Bollywood and Cricket in anything they sponsor. What is dangerous is the eroding space- financial or otherwise of serious arts. Because of its media and money power, Bollywood is fast occupying the mindspace and emotional space of generations of Indians. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ -

Koel Chatterjee Phd Thesis

Bollywood Shakespeares from Gulzar to Bhardwaj: Adapting, Assimilating and Culturalizing the Bard Koel Chatterjee PhD Thesis 10 October, 2017 I, Koel Chatterjee, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 10th October, 2017 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the patience and guidance of my supervisor Dr Deana Rankin. Without her ability to keep me focused despite my never-ending projects and her continuous support during my many illnesses throughout these last five years, this thesis would still be a work in progress. I would also like to thank Dr. Ewan Fernie who inspired me to work on Shakespeare and Bollywood during my MA at Royal Holloway and Dr. Christie Carson who encouraged me to pursue a PhD after six years of being away from academia, as well as Poonam Trivedi, whose work on Filmi Shakespeares inspired my research. I thank Dr. Varsha Panjwani for mentoring me through the last three years, for the words of encouragement and support every time I doubted myself, and for the stimulating discussions that helped shape this thesis. Last but not the least, I thank my family: my grandfather Dr Somesh Chandra Bhattacharya, who made it possible for me to follow my dreams; my mother Manasi Chatterjee, who taught me to work harder when the going got tough; my sister, Payel Chatterjee, for forcing me to watch countless terrible Bollywood films; and my father, Bidyut Behari Chatterjee, whose impromptu recitations of Shakespeare to underline a thought or an emotion have led me inevitably to becoming a Shakespeare scholar. -

Acdsee Proprint

BULK RATE U.S. POSTAGE PAID Permit No. 2419 lPE lPITClHl K.C., Mo. FREE FREE VOL. II NO. 1 YOU'LL NEVER GET RICH READING THE PITCH FEBRUARY 1981 FBIIRUARY II The 8-52'5 Meet BUDGBT The Rev. in N.Y. Third World Bit List .ONTHI l ·TRIVIA QUIZ· WHAT? SQt·1E RECORD PRICES ARE ACTUALLY ~~nll .815 m wi. i .••lIIi .... lllallle,~<M0,~ CGt4J~G ·DOWN·?····· S€f ·PAGE: 3. FOR DH AI LS , prizes PAGE 2 THE PENNY PITCH LETTERS Dec. 29,1980 Dear Warren, Over the years, Kansas Attorney General's have done many strange things. Now the Kansas Attorney General wants to stamp out "Mumbo Jumbo." 4128 BROADWAY KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI 64111 Does this mean the "Immoral Minority" (816) 561·1580 will be banned from Kansas? Is being banned from Kansas a hardship? Edi tor ....••..•••.• vifarren Stylus Morris Martin Contributing vlriters this issue: Raytown, Mo. P.S. He probably doesn't like dreadlocks Rev. Dwight Frizzell, Lane & Dave from either. GENCO labs, Blind Teddy Dibble, I-Sheryl, Ie-Roths, Lonesum Chuck, Mr.D-Conn, Le Roi, Rage n i-Rick, P. Minkin, Lindsay Shannon, Mr. P. Keenan, G. Trimble, Jan. 26, 1981 debranderson, M. Olson Dear Editor, Inspiration this issue: How come K. C. radio stations never Fred de Cordova play, The Inmates "I thought I heard a Heartbeat", Roy Buchanan "Dr. Rock & Roll" Peter Green, "Loser Two Times", Marianne r,------:=~--~-__l "I don' t care what they say about Faithfull, "Broken English", etc, etc,? being avant garde or anything else. How come? Frankly, call me square if you want Is this a plot against the "Immoral to. -

Vallelyn Phd2018.Pdf

UCC Library and UCC researchers have made this item openly available. Please let us know how this has helped you. Thanks! Title Beyond the tune: new Irish music Author(s) Vallely, Niall Publication date 2018 Original citation Vallely, N. 2018. Beyond the tune: new Irish music. PhD Thesis, University College Cork. Type of publication Doctoral thesis Rights © 2018, Niall Vallely. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Embargo information Not applicable Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/7021 from Downloaded on 2021-10-10T08:36:19Z Ollscoil na hÉireann, Corcaigh National University of Ireland, Cork Beyond the Tune: New Irish Music Thesis presented by Niall Vallely For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University College Cork School of Music and Theatre Head of School: Prof. Jools Gilson Supervisor: John Godfrey 2018 2 Table of Contents Declaration 4 List of accompanying musical scores and CD 5 Acknowledgements 6 Preface 7 Chapter 1 Introduction and Background 8 Education 9 Performance 12 Impact of cross-cultural music 14 Chapter 2 Context and Influences 17 Seán Ó Riada 17 Shaun Davey 18 Mícheál Ó Súilleabháin 19 Other Composers 21 Beyond Genre 23 Chapter 3 Artistic Statement 26 Compositions 27 The Red Tree 28 Sondas 35 Ó Riada Room 37 Time Flying 38 throughother 42 Nothing Else 44 Connolly’s Chair 46 Concertina Concerto 47 Conclusion 50 Appendix 1 List of compositions used in PhD 51 Appendix 2 Complete list of compositions to date 54 Discography 75 3 Bibliography 79 4 Declaration I, Niall Vallely, declare that this dissertation is the result of my own work, except as acknowledged by appropriate reference in the text. -

Port Na Bpúcaí Title Code 1 Altan 25Th Anniversary Celebration with The

Port na bPúcaí Title Code Aberlour's Save the last drop 9,95 1 Abbey Ceili Band Bruach at StSuiain 9,95 1 Afro Celt Sound System POD (CD & DVD) CDRW 116 18,95 Afro Celt Sound System Vol 1 - Sound Magic CDRW61 14,95 Afro Celt Sound System Vol 2 - Release CDRW76 14,95 1 Afro Celt Sound System Vol 3 - Further in time CDRW96 14,95 Afro Celt Sound System Anatomic CDRW133 16,95 Afro Celt Sound System Seed CDRWG111 Altan 25th Anniversary Celebration with the ALT001 16,95 2 RTE concert orchestra Altan Altan ( Frankie & Mairead ) GLCD 1078 16,95 Altan another sky... 724384883829 12,95 Altan Best of, The (2CDs) GLCD 1177 16,95 1 Altan The best of Altan - The Songs 7, 24354E+11 9,95 Altan Blackwater CDV2796 12,95 Altan Blue Idol, The CDVE961/ 8119552 16,95 Altan Finest, The CCCD100 8,95 Altan First ten years 1986-1995, The GLCD 1153 14,95 Altan Glen Nimhe - The Poison Glen COM4571 16,95 Altan harvest storm GLCD 1117 16,95 Altan horse with a heart GLCD 1095 16,95 Altan island angel GLCD 1137 16,95 1 Altan Local ground VERTCD069 19,95 Altan Runaway sunday CDV2836 12,95 Altan Red crow, The GLCD 1109 16,95 Altan The widening gyre 16,95 1 Ancient voice of Ireland Haunting Irish melodies 9,95 2 Anúna Anúna DANU21 9,95 1 Anúna Deep dead blue DANU020 14,95 Anúna Illumination DANU029 Anúna Invocation DANU015 14,95 Anúna Sanctus DANU025 14,95 Anúna Winter Songs DANU 16 14,95 Arcade Fire The subburbs 6,95 5 Arcady After the ball.. -

Roxbox by Artist (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Play Feat

RoxBox by Artist (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Play Feat. Thomas Jules & Bartender Jucxi D Blackout Careless Whisper Other Side 2 Unlimited 10 Years No Limit Actions & Motives 20 Fingers Beautiful Short Dick Man Drug Of Choice 21 Demands Fix Me Give Me A Minute Fix Me (Acoustic) 2Pac Shoot It Out Changes Through The Iris Dear Mama Wasteland How Do You Want It 10,000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Because The Night 2Pac Feat Dr. Dre Candy Everybody Wants California Love Like The Weather 2Pac Feat. Dr Dre More Than This California Love These Are The Days 2Pac Feat. Elton John Trouble Me Ghetto Gospel 101 Dalmations 2Pac Feat. Eminem Cruella De Vil One Day At A Time 10cc 2Pac Feat. Notorious B.I.G. Dreadlock Holiday Runnin' Good Morning Judge 3 Doors Down I'm Not In Love Away From The Sun The Things We Do For Love Be Like That Things We Do For Love Behind Those Eyes 112 Citizen Soldier Dance With Me Duck & Run Peaches & Cream Every Time You Go Right Here For You Here By Me U Already Know Here Without You 112 Feat. Ludacris It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) Hot & Wet Kryptonite 112 Feat. Super Cat Landing In London Na Na Na Let Me Be Myself 12 Gauge Let Me Go Dunkie Butt Live For Today 12 Stones Loser Arms Of A Stranger Road I'm On Far Away When I'm Gone Shadows When You're Young We Are One 3 Of A Kind 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Mozart, but Not Only

Mozart, but not only... A dialogue between traditional, classical and contemporary music © Michel Granger Le Prix international de Marrakech 2005 a été décerné à l’association Mélodie pour le Dialogue entre les Civilisations dans le domaine de l’art et de la créativité à travers l’interaction entre les mélodies et les instruments de musique de différentes cultures«. Pour plus d’informations sur le Dialogue entre les Civilisations, consultez le site Internet : www.unesco.org/dialogue Composition et mise en page : G. Ville Imprimé dans les ateliers de l’UNESCO © Association « Mélodie pour le dialogue entre les civilisations », 2005 Message from Director-General of UNESCO o celebrate its 60th anniversary this year, UNESCO has embarked on a stimulating and broad-based programme of conferences, discussions, reflections, artistic performances, musical programmes tand outreach events. While these activities will stretch well into next year in an effort of sustained commitment and renewal, the day of 16 November stands out: this was the day the UNESCO Constitution was adopted. Hence, it is the Organization’s official birthday. Today’s concert has been organized by the Melody for Dialogue among Civilizations Association and is a special gift to the entire UNESCO community on the occasion of the jubilee. It comes in the context of promoting dialogue among civilizations, cultures and peoples, which is one of UNESCO’s major tasks. Indeed, it is no accident that 16 November coincides with the International Day of Tolerance, which underlines one of the key values espoused by the international community and which is at the heart of all dialogue. -

THE GARY MOORE DISCOGRAPHY (The GM Bible)

THE GARY MOORE DISCOGRAPHY (The GM Bible) THE COMPLETE RECORDING SESSIONS 1969 - 1994 Compiled by DDGMS 1995 1 IDEX ABOUT GARY MOORE’s CAREER Page 4 ABOUT THE BOOK Page 8 THE GARY MOORE BAND INDEX Page 10 GARY MOORE IN THE CHARTS Page 20 THE COMPLETE RECORDING SESSIONS - THE BEGINNING Page 23 1969 Page 27 1970 Page 29 1971 Page 33 1973 Page 35 1974 Page 37 1975 Page 41 1976 Page 43 1977 Page 45 1978 Page 49 1979 Page 60 1980 Page 70 1981 Page 74 1982 Page 79 1983 Page 85 1984 Page 97 1985 Page 107 1986 Page 118 1987 Page 125 1988 Page 138 1989 Page 141 1990 Page 152 1991 Page 168 1992 Page 172 1993 Page 182 1994 Page 185 1995 Page 189 THE RECORDS Page 192 1969 Page 193 1970 Page 194 1971 Page 196 1973 Page 197 1974 Page 198 1975 Page 199 1976 Page 200 1977 Page 201 1978 Page 202 1979 Page 205 1980 Page 209 1981 Page 211 1982 Page 214 1983 Page 216 1984 Page 221 1985 Page 226 2 1986 Page 231 1987 Page 234 1988 Page 242 1989 Page 245 1990 Page 250 1991 Page 257 1992 Page 261 1993 Page 272 1994 Page 278 1995 Page 284 INDEX OF SONGS Page 287 INDEX OF TOUR DATES Page 336 INDEX OF MUSICIANS Page 357 INDEX TO DISCOGRAPHY – Record “types” in alfabethically order Page 370 3 ABOUT GARY MOORE’s CAREER Full name: Robert William Gary Moore. Born: April 4, 1952 in Belfast, Northern Ireland and sadly died Feb. -

2 Records Aug 15 2021

Sept 2, 2021 Latest additions indicated by asterisk (*) C * ? & THE MYSTERIANS 99 TEARS / MIDNIGHT HOUR 10 CC I'M NOT IN LOVE/CHANNEL SWIMMER 1910 FRUITGUM CO, SIMON SAYS REFLECTIONS FROM THE LOOKING GLASS 1910 FRUITGUM CO. SIMON SAYS/REFLECTIONS FROM THE LOOKING GLASS 2 R 1910 FRUITGUM CO. INDIAN GIVER / POW WOW 3 SHARPES QUARTET LES MY LOVE WAS NOT TRUE LOVE/BELLE ST. JOHN R 49TH PARALLEL NOW THAT I'M A MAN / TALK TO ME R 6 CYLINDER AIN'T NOBODY HERE BUT US CHICKENS / STRONG WOMAN.... 6 CYLINDER AIN'T NOBODY HERE BUT US CHICKENS / STRONG WOMAN'S LOVE 8TH DAY IF I COULD SEE THE LIGHT / IF I COULD SEE THE LIGHT (INST) 9 LAFALCE BROTHERS MARIA, MARIA, MARIA/THE DEVIL'S HIGHWAY A TASTE OF HONEY SUKAYAKI / DON'T YOU LEAD ME ON A*TEENS DANCING QUEEN / MAMMA MIA A*TEENS DANCING QUEEN / MAMMA MIA AARON LEE ONLY HUMAN / EMPTY HEART A * ABBA KNOWING ME KNOWING YOU / HAPPY HAWAII A * ABBA MONEY MONEY MONEY / CRAZY WORLD ABBOTT GREGORY SHAKE YOU DOWN / WAIT UNTIL TOMORROW ABBOTT RUSS SPACE INVADERS MEET PURPLE PEOPLE EATER/COUNTRY COOPERMAN ABC ALL OF MY HEART / OVERTURE ABC ALL OF MY HEART / OVERTURE ABC THAT WAS THEN BUT THIS IS NOW / VERTIGO ABC THE LOOK OF LOVE / THE LOOK OF LOVE ABDUL PAULA MY LOVE IS FOR REAL / SAY I LOVE YOU ABDUL PAULA I DIDN'T SAY I LOVE YOU/MY LOVE IS FOR REAL ABDUL PAULA IT'S JUST THE WAY YOU LOVE ME/DUB MIX . PICTURE SLEEVE ABDUL PAULA THE PROMISE OF A NEW DAY/THE PROMISE OF A NEW DAY ABDUL PAULA VIBEOLOGY/VIBEOLOGY ABRAMS MISS MILL VALLEY/THE HAPPIEST DAY OF MY LIFE ABRAMSON RONNEY NEVER SEEM TO GET ALONG WITHOUT YOU/TIME -

Unit Revised Reference List

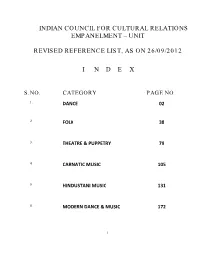

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT – UNIT REVISED REFERENCE LIST, AS ON 26/09/2012 I N D E X S.NO. CATEGORY PAGE NO 1. DANCE 02 2. FOLK 38 3. THEATRE & PUPPETRY 79 4. CARNATIC MUSIC 105 5. HINDUSTANI MUSIC 131 6. MODERN DANCE & MUSIC 172 1 INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMEMT SECTION REVISED REFERENCE LIST FOR DANCE - AS ON 26/09/2012 S.NO. CATEGORY PAGE NO 1. BHARATANATYAM 3 – 11 2. CHHAU 12 – 13 3. KATHAK 14 – 19 4. KATHAKALI 20 – 21 5. KRISHNANATTAM 22 6. KUCHIPUDI 23 – 25 7. KUDIYATTAM 26 8. MANIPURI 27 – 28 9. MOHINIATTAM 29 – 30 10. ODISSI 31 – 35 11. SATTRIYA 36 12. YAKSHAGANA 37 2 REVISED REFERENCE LIST FOR DANCE AS ON 26/09/2012 BHARATANATYAM OUTSTANDING 1. Ananda Shankar Jayant (Also Kuchipudi) (Up) 2007 2. Bali Vyjayantimala 3. Bhide Sucheta 4. Chandershekar C.V. 03.05.1998 5. Chandran Geeta (NCR) 28.10.1994 (Up) August 2005 6. Devi Rita 7. Dhananjayan V.P. & Shanta 8. Eshwar Jayalakshmi (Up) 28.10.1994 9. Govind (Gopalan) Priyadarshini 03.05.1998 10. Kamala (Migrated) 11. Krishnamurthy Yamini 12. Malini Hema 13. Mansingh Sonal (Also Odissi) 14. Narasimhachari & Vasanthalakshmi 03.05.1998 15. Narayanan Kalanidhi 16. Pratibha Prahlad (Approved by D.G March 2004) Bangaluru 17. Raghupathy Sudharani 18. Samson Leela 19. Sarabhai Mallika (Up) 28.10.1994 20. Sarabhai Mrinalini 21. Saroja M K 22. Sarukkai Malavika 23. Sathyanarayanan Urmila (Chennai) 28.10.94 (Up)3.05.1998 24. Sehgal Kiran (Also Odissi) 25. Srinivasan Kanaka 26. Subramanyam Padma 27.