Experiencing Celtic Culture Through Music Practice on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genealogy Basics – Family History, Educators in My Tobin Family

Genealogy Basics – Family History, Educators in My Tobin Family By Joe Petrie INTRODUCTION Many Genealogy organizations have the word History or Historical in the title. For example, Cape Breton Genealogy and Historical Association (CBGHA) and Family History Society of Newfoundland and Labrador (FHSNL) are a couple of organizations that use the terms. In a Genealogy Basic article about the United Kingdom and Ireland web site (Genuki), I used the Genuki site’s definition of Family History. Suggest that you read it. The article is in cbgen Records\Research. It is labeled “Genealogy Basics – An Amazing Irish Web Site”. My title of the article indicates that the Genuki site had a fantastic Getting Started link. Other tabs on the site were not reviewed. My simple view of Family History is: If the author includes non-verifiable oral history, it is a Family History document. My Register Reports in Records\Family are Family History Reports. Please note that a report by a paid professional genealogist often will only include verifiable facts. Some professionals go beyond one verifiable fact. For example, members of the Association of Professional Genealogists try to verify using two verifiable sources. Also, please remember that most genealogy teachers encourage students to start with relatives. A few teachers even say that the facts should be verified. Some teachers start on-line with Census records. Latest US Census records are for 1940. Canada Census records are for 1921. BACKGROUND I’ll cover eight of generations of my Tobin direct line family or siblings who taught (or still teach) starting with Patrick Tobin who immigrated from Gowran, Kilkenney, Ireland to Northern Bay, Bay DeVerde, Newfoundland in the early 1800s. -

Celtic-Colours-Guide-2019-1

11-19 October 2019 • Cape Breton Island Festival Guide e l ù t h a s a n ò l l g r a t e i i d i r h . a g L s i i s k l e i t a h h e t ò o e c b e , a n n i a t h h a m t o s d u o r e r s o u ’ a n d n s n a o u r r a t I l . s u y l c a g n r a d e h , n t c e , u l n l u t i f u e r h l e t i u h E o e y r r e h a t i i s w d h e e e d v i p l , a a v d i b n r a a t n h c a e t r i a u c ’ a a h t a n a u h c ’ a s i r h c a t l o C WELCOME Message from the Atlantic Canada Message de l’Agence de promotion A Message from the Honourable Opportunities Agency économique du Canada atlantique Stephen McNeil, M.L.A. Premier Welcome to the 2019 Celtic Colours Bienvenue au Celtic Colours On behalf of the Province of Nova International Festival International Festival 2019 Scotia, I am delighted to welcome you to the 2019 Celtic Colours International Tourism is a vital part of the Atlantic Le tourisme est une composante Festival. -

Savannah Scottish Games & Highland Gathering

47th ANNUAL CHARLESTON SCOTTISH GAMES-USSE-0424 November 2, 2019 Boone Hall Plantation, Mount Pleasant, SC Judge: Fiona Connell Piper: Josh Adams 1. Highland Dance Competition will conform to SOBHD standards. The adjudicator’s decision is final. 2. Pre-Premier will be divided according to entries received. Medals and trophies will be awarded. Medals only in Primary. 3. Premier age groups will be divided according to entries received. Cash prizes will be awarded as follows: Group 1 Awards 1st $25.00, 2nd $15.00, 3rd $10.00, 4th $5.00 Group 2 Awards 1st $30.00, 2nd $20.00, 3rd $15.00, 4th $8.00 Group 3 Awards 1st $50.00, 2nd $40.00, 3rd $30.00, 4th $15.00 4. Trophies will be awarded in each group. Most Promising Beginner and Most Promising Novice 5. Dancer of the Day: 4 step Fling will be danced by Premier dancer who placed 1st in any dance. Primary, Beginner and Novice Registration: Saturday, November 2, 2019, 9:00 AM- Competition to begin at 9:30 AM Beginner Steps Novice Steps Primary Steps 1. Highland Fling 4 5. Highland Fling 4 9. 16 Pas de Basque 2. Sword Dance 2&1 6. Sword Dance 2&1 10. 6 Pas de Basque & 4 High Cuts 3. Seann Triubhas 3&1 7. Seann Triubhas 3&1 11. Highland Fling 4 4. 1/2 Tulloch 8. 1/2 Tulloch 12. Sword Dance 2&1 Intermediate and Premier Registration: Saturday, November 2, 2019, 12:30 PM- Competition to begin at 1:00 PM Intermediate Premier 15 Jig 3&1 20 Hornpipe 4 16 Hornpipe 4 21 Jig 3&1 17 Highland Fling 4 22. -

1-888-355-7744 Toll Free 902-567-3000 Local

celtic-colours•com REMOVE MAP TO USE Official Festival Map MAP LEGEND Community Event Icons Meat Cove BAY ST. LAWRENCE | Capstick Official Learning Outdoor Participatory Concert Opportunities Event Event ST. MARGARET'S VILLAGE | ASPY BAY | North Harbour Farmers’ Visual Art / Community Local Food White Point Market Heritage Craft Meal Product CAPE NORTH | Smelt Brook Map Symbols Red River SOUTH HARBOUR | Pleasant Bay Participating Road BIG INTERVALE | Community Lone Shieling NEIL’S HARBOUR | Dirt Road Highway Cabot Trail CAPE BRETON HIGHLANDS NATIONAL PARK Cap Rouge TICKETS & INFORMATION 1-888-355-7744 TOLL FREE Keltic Lodge 902-567-3000 LOCAL CHÉTICAMP | Ingonish Beach INGONISH | Ingonish Ferry La Pointe GRAND ÉTANG HARBOUR | Wreck Cove Terre Noire Skir Dhu BELLE CÔTE | ATLANTIC.CAA.CA French River Margaree Harbour North Shore INDIAN BROOK | Chimney Corner East Margaree MARGAREE CENTER | Tarbotvale NORTH EAST MARGAREE | ENGLISHTOWN | Dunvegan MARGAREE FORKS | Big Bras d’Dor NORTH RIVER | SYDNEY MINES | Lake O’Law 16 BROAD COVE | SOUTH WEST MARGAREE | 17 18 15 Bras d’Dor 19 Victoria NEW WATERFORD | 12 14 20 21 Mines Scotchtown SOUTH HAVEN | 13 Dominion INVERNESS | 2 South Bar GLACE BAY | SCOTSVILLE | MIDDLE RIVER | 11 NORTH SYDNEY | ST. ANN'S | Donkin STRATHLORNE | Big Hill BOULARDERIE | 3 PORT MORIEN | 125 SYDNEY | L 10 Westmount A BADDECK | 4 K Ross Ferry E Barachois A COXHEATH | I MEMBERTOU | N 5 S East Lake Ainslie 8 L I 9 7 E 6 SYDNEY RIVER | WAGMATCOOK7 | HOWIE CENTRE | WEST MABOU | 8 Homeville West Lake Ainslie PRIME BROOK | BOISDALE -

WORKSHOP: Around the World in 30 Instruments Educator’S Guide [email protected]

WORKSHOP: Around The World In 30 Instruments Educator’s Guide www.4shillingsshort.com [email protected] AROUND THE WORLD IN 30 INSTRUMENTS A MULTI-CULTURAL EDUCATIONAL CONCERT for ALL AGES Four Shillings Short are the husband-wife duo of Aodh Og O’Tuama, from Cork, Ireland and Christy Martin, from San Diego, California. We have been touring in the United States and Ireland since 1997. We are multi-instrumentalists and vocalists who play a variety of musical styles on over 30 instruments from around the World. Around the World in 30 Instruments is a multi-cultural educational concert presenting Traditional music from Ireland, Scotland, England, Medieval & Renaissance Europe, the Americas and India on a variety of musical instruments including hammered & mountain dulcimer, mandolin, mandola, bouzouki, Medieval and Renaissance woodwinds, recorders, tinwhistles, banjo, North Indian Sitar, Medieval Psaltery, the Andean Charango, Irish Bodhran, African Doumbek, Spoons and vocals. Our program lasts 1 to 2 hours and is tailored to fit the audience and specific music educational curriculum where appropriate. We have performed for libraries, schools & museums all around the country and have presented in individual classrooms, full school assemblies, auditoriums and community rooms as well as smaller more intimate settings. During the program we introduce each instrument, talk about its history, introduce musical concepts and follow with a demonstration in the form of a song or an instrumental piece. Our main objective is to create an opportunity to expand people’s understanding of music through direct expe- rience of traditional folk and world music. ABOUT THE MUSICIANS: Aodh Og O’Tuama grew up in a family of poets, musicians and writers. -

Ch4 Website Links with Audio

Chapter 4 – Website links with audio British Isles England o RP – www.dialectsarchive.com/england-63 (female, 1954, white, Surrey (and abroad)) o South-West England – www.dialectsarchive.com/england-70 (female, 21, 1986, white, Torquay (Devon)) o South-East – www.dialectsarchive.com/england-91 (female, 46, 1966, white, Southampton (Hampshire) and USA) o London – www.dialectsarchive.com/england-62 (female, 21, 1985, white and Sri Lankan, South Norwood (South-East London)) o East – www.dialectsarchive.com/england-47 (male, 22, 1980, white, Cambridge) o East Midlands – www.dialectsarchive.com/england-66 (male, 40s, 1962, white, Gainsborough (Lincolnshire) and Yorkshire) o West Midlands – www.dialectsarchive.com/england-53 (female, 56, 1947, white, Gaydon (Warwickshire)) o Yorkshire and Humber – www.dialectsarchive.com/england-83 (male, 27, 1982, white, Skipton (North Yorkshire)) o North-West – www.dialectsarchive.com/england-44 (female, 31, 1970, white, Kirkdale (Liverpool) and Manchester) o North-East – www.dialectsarchive.com/england-13 (female, 43, 1957, white, Newcastle (Tyne and Wear)) (only one for comma gets a cure) o North-East – www.dialectsarchive.com/england-26 (female, 19, 1980, white, Gateshead (Tyne and Wear)) Wales o www.dialectsarchive.com/wales-6 (female, 20, 1989, Caucasian, Hirwaun and Carmarthen) Scotland o www.dialectsarchive.com/scotland-12 (male, 22, 1980, Caucasian, New Galloway and Edinburgh) Northern Ireland o www.dialectsarchive.com/northern-ireland-3 (female, 20s, Irish/Caucasian, Belfast) Republic of Ireland -

The Open Back of the Open-Back Banjo

HDP: 13 { 02 glasswork by M. Desy The Open Back of the Open-Back Banjo David Politzer∗ California Institute of Technology (Dated: December 2, 2013) ...in which a simple question turned into a great adventure and even got answered. (Of course, you might already know the answer yourself.) In a triumph of elementary physics, six measured numbers receive a satisfactory account using two adjustable parameters. ∗[email protected]; http://www.its.caltech.edu/~politzer; 452-48 Caltech, Pasadena CA 91125 2 The Open Back of the Open-Back Banjo I. THE RIM QUESTION The question seemed straightforward. What is the impact of rim height on the sound of an open-back banjo? FIG. 1. an open-back banjo's open back 3 mylar (or skin) head metal flange rim height drum rim wall open back resonator back (Which head is bigger? Auditory (as opposed to optical) illusions only came into their own with the development of digital sound.) FIG. 2. schematic banjo pot cross sections There are a great many choices in banjo design, construction, and set-up. For almost all of them, there is consensus among players and builders on the qualitative effect of possible choices. Just a few of the many are: string material and gauge; drum head material, thickness, and tension; neck wood and design; rim material and weight; tailpiece design and height; tone ring design and material. However, there is no universal ideal of banjo perfection. Virtually every design that has ever existed is still played with gusto, and new ones of those designs are still in production. -

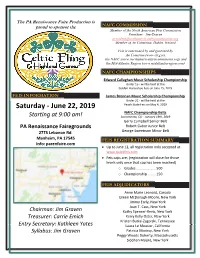

June 22, 2019

The PA Renaissance Faire Production is proud to sponsor the NAFC COMMISSION Member of the North American Feis Commission President: Jim Graven [email protected] Member of An Coimisiun, Dublin, Ireland Feis is sanctioned by and governed by An Comisiun (www.clrg.ie), the NAFC (www.northamericanfeiscommission.org) and the Mid-Atlantic Region (www.midatlanticregion.com) NAFC CHAMPIONSHIPS Edward Callaghan Music Scholarship Championship Under 15 - will be held at the Golden Horseshoe Feis on June 15, 2019 FEIS INFORMATION James Brennan Music Scholarship Championship Under 21 - will be held at the Peach State Feis on May 4, 2019 Saturday - June 22, 2019 NAFC Championship Belts Starting at 9:00 am! Sacramento, CA - January 19th, 2019 Gerry Campbell Senior Belt PA Renaissance Fairegrounds Robert Gabor Junior Belt 2775 Lebanon Rd. George Sweetnam Minor Belt Manheim, PA 17545 FEIS REGISTRATION SUMMARY Info: parenfaire.com Up to June 12, all registration only accepted at www.quickfeis.com Feis caps are: (registration will close for those levels only once that cap has been reached) o Grades ..................... 500 o Championship ......... 150 FEIS ADJUDICATORS Anne Marie Leonard, Canada Eileen McDonagh-Moore, New York Jimmy Early, New York Joan T. Cass, New York Chairman: Jim Graven Kathy Spencer-Revis, New York Treasurer: Carrie Emich Kerry Kelly Oster, New York Kristen Butke-Zagorski, Tennessee Entry Secretary: Kathleen Yates Laura Le Meusier, California Syllabus: Jim Graven Patricia Morissy, New York Peggy Woods Doherty, Massachusetts Siobhan Moore, New York COMPETITION FEES CELTIC FLING FEIS FESTIVAL Feis Admission includes ONE day ticket to the festival Competition Fees FEES (you can purchase a second day ticket at registration) Solo Dancing / TR / Sets / Non-Dance Kick-off concert on Friday featuring great performers! $ 10 Bring your appetite and enjoy delicious foods and (per competitor and per dance) refreshing wines, ales & ciders while listening to the live Preliminary Championship music! Gates open at 4PM. -

THE JOHN BYRNE BAND the John Byrne Band Is Led by Dublin Native and Philadelphia-Based John Byrne

THE JOHN BYRNE BAND The John Byrne Band is led by Dublin native and Philadelphia-based John Byrne. Their debut album, After the Wake, was released to critical acclaim on both sides of the Atlantic in 2011. With influences ranging from Tom Waits to Planxty, John’s songwriting honors and expands upon the musical and lyrical traditions of his native and adopted homes. John and the band followed up After the Wake in early 2013 with an album of Celtic and American traditional tunes. The album, Celtic/Folk, pushed the band on to the FolkDJ Charts, reaching number 36 in May 2015. Their third release, another collection of John Byrne originals, entitled “The Immigrant and the Orphan”, was released in Sept 2015. The album, once again, draws heavily on John’s love of Americana and Celtic Folk music and with the support of DJs around the country entered the FolkDJ Charts at number 40. Critics have called it “..a powerful, deeply moving work that will stay with you long after you have heard it” (Michael Tearson-Sing Out); “The Vibe of it (The Immigrant and the Orphan) is, at once, as rough as rock and as elegant as a calm ocean..each song on this album carries an honesty, integrity and quiet passion that will draw you into its world for years to come” (Terry Roland – No Depression); “If any element of Celtic, Americana or Indie-Folk is your thing, then this album is an absolute yes” (Beehive Candy); “It’s a gorgeous, nostalgic record filled with themes of loss, hope, history and lost loves; everything that tugs at your soul and spills your blood and guts…The Immigrant and the Orphan scorches the earth and emerges tough as nails” (Jane Roser – That Music Mag) The album was released to a sold-out crowd at the storied World Café Live in Philadelphia and 2 weeks later to a sold-out crowd at the Mercantile in Dublin, Ireland. -

Traditional Music of Scotland

Traditional Music of Scotland A Journey to the Musical World of Today Abstract Immigrants from Scotland have been arriving in the States since the early 1600s, bringing with them various aspects of their culture, including music. As different cultures from around Europe and the world mixed with the settled Scots, the music that they played evolved. For my research project, I will investigate the progression of “traditional” Scottish music in the United States, and how it deviates from the progression of the same style of music in Scotland itself, specifically stylistic changes, notational changes, and changes in popular repertoire. I will focus on the relationship of this progression to the interactions of the two countries throughout history. To conduct my research, I will use non-fiction sources on the history of Scottish music, Scottish culture and music in the United States, and Scottish immigration to and interaction with the United States. Beyond material sources, I will contact my former Scottish fiddle teacher, Elke Baker, who conducts extensive study of ethnomusicology relating to Scottish music. In addition, I will gather audio recordings of both Scots and Americans playing “traditional” Scottish music throughout recent history to compare and contrast according to their dates. My background in Scottish music, as well as in other American traditional music styles, will be an aid as well. I will be able to supplement my research with my own collection of music by close examination. To culminate my project, I plan to compose my own piece of Scottish music that incorporates and illustrates the progression of the music from its first landing to the present. -

Acdsee Proprint

BULK RATE U.S. POSTAGE PAID Permit No. 2419 lPE lPITClHl K.C., Mo. FREE FREE VOL. II NO. 1 YOU'LL NEVER GET RICH READING THE PITCH FEBRUARY 1981 FBIIRUARY II The 8-52'5 Meet BUDGBT The Rev. in N.Y. Third World Bit List .ONTHI l ·TRIVIA QUIZ· WHAT? SQt·1E RECORD PRICES ARE ACTUALLY ~~nll .815 m wi. i .••lIIi .... lllallle,~<M0,~ CGt4J~G ·DOWN·?····· S€f ·PAGE: 3. FOR DH AI LS , prizes PAGE 2 THE PENNY PITCH LETTERS Dec. 29,1980 Dear Warren, Over the years, Kansas Attorney General's have done many strange things. Now the Kansas Attorney General wants to stamp out "Mumbo Jumbo." 4128 BROADWAY KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI 64111 Does this mean the "Immoral Minority" (816) 561·1580 will be banned from Kansas? Is being banned from Kansas a hardship? Edi tor ....••..•••.• vifarren Stylus Morris Martin Contributing vlriters this issue: Raytown, Mo. P.S. He probably doesn't like dreadlocks Rev. Dwight Frizzell, Lane & Dave from either. GENCO labs, Blind Teddy Dibble, I-Sheryl, Ie-Roths, Lonesum Chuck, Mr.D-Conn, Le Roi, Rage n i-Rick, P. Minkin, Lindsay Shannon, Mr. P. Keenan, G. Trimble, Jan. 26, 1981 debranderson, M. Olson Dear Editor, Inspiration this issue: How come K. C. radio stations never Fred de Cordova play, The Inmates "I thought I heard a Heartbeat", Roy Buchanan "Dr. Rock & Roll" Peter Green, "Loser Two Times", Marianne r,------:=~--~-__l "I don' t care what they say about Faithfull, "Broken English", etc, etc,? being avant garde or anything else. How come? Frankly, call me square if you want Is this a plot against the "Immoral to. -

CARMEN DAAH Mezzo-Soprano with J. Hunter Macmillan, Piano Recorded London, January 1925 MC-6847 Kishmul's Galley (“Songs Of

1 CARMEN DAAH Mezzo-soprano with J. Hunter MacMillan, piano Recorded London, January 1925 MC-6847 Kishmul’s galley (“songs of the Hebrides”) (trad. arr. Marjorie Kennedy Fraser) Bel 705 MC-6848 The spinning wheel (Dunkler) Bel 705 MC-6849 Coming through the rye (Robert Burns; Robert Brenner) Bel 706 MC-6850 O rowan tree – ancient Scots song (trad. arr. J. H. MacMillan) Bel 707 MC-6851 Jock o’ Hazeldean (Walter Scott; trad. arr. J. Hunter MacMillan Bel 706 MC-6853 The herding song (trad. arr. Mrs. Kennedy Fraser) Bel 707 THE DAGENHAM GIRL PIPERS (formed 1930) Led by Pipe-Major Douglas Taylor. 12 pipers, 4 drummers Recorded Chelsea Town Hall, King’s Road, London, Saturday, 19th. November 1932 GB-5208-1/2 Lord Lovat’s lament; Bruce’s address – lament (both trad) Panachord 25365; Rex 9584 GB-5209-1/2 Earl of Mansfield – march (John McEwan); Lord Lovat’s – strathspey (trad); Mrs McLeod Of Raasay – reel (Alexander MacDonald) Panachord 25365; Rex 9584 GB-5210-1 Highland Laddie – march (trad); Lady Madelina Sinclair – strathspey (Niel Gow); Tail toddle reel (trad) Panachord 25370; Rex 9585 GB-5211-3 An old Highland air (trad) Panachord 25370; Rex 9585 Pipe Major Peggy Isis (solos); 15 pipers; 4 side drums; 1 bass drum. Recorded Studio No. 2, 3 Abbey Road, London, Tuesday, 26th. March 1957 Military marches – intro. Scotland the brave; Mairi’s wedding; Athole Highlanders (all trad) Par GEP-8634(EP); CapUS T-10125(LP) Pipes in harmony – intro. Maiden of Morven (trad); Green hills of Tyrol (Gioacchino Rossini. arr. P/M John MacLeod) Par GEP-8634(EP); CapUS T-10125(LP) Corn rigs – march (trad); Monymusk – strathspey (Daniel Dow); Reel o’ Tulloch (John MacGregor); Highland laddie (trad) Par GEP-8634(EP); CapUS T-10125(LP) Quick marches – intro.