Vallelyn Phd2018.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dino Saluzzi, Anja Lechner Ojos Negros

ECM Dino Saluzzi, Anja Lechner Ojos Negros Dino Saluzzi: bandoneon; Anja Lechner: violoncello ECM 1991 CD 6025 170 9757 (5) Release: March 2007 “As close to perfection as any music-making I can recently recall" Richard Cook, Jazz Review, on the Saluzzi/Lechner duo in concert Chamber music with inspirational roots in Argentinean traditions: “Ojos Negros” puts the emphasis on Dino Saluzzi’s finely-crafted compositions –and adds the beautiful old tango by Vicente Greco that is the album’s title track. Interplay and improvisation also have roles to play in a recording that follows six years of duo concerts as well as ten years of collaboration between bandoneon master Saluzzi and the Rosamunde Quartet, of which cellist Anja Lechner is a founder member. They have taken their time to get this right. A classical musician firstly, Anja Lechner’s interest in tango goes back some 25 years, when she formed a duo with pianist Peter Ludwig to play their German interpretations of the idiom. She gave her first concerts in Argentina in the early 1980s and made a point of looking for tango’s master musicians. But she first encountered Dino Saluzzi at a Munich concert where he played solo bandoneon. “He was playing a music that was really his own. When we finally began to play together I can say that I entered a new world.” The shared work has been a gradual process of becoming freer with the material while respecting it, resulting in a very integrated music. Saluzzi praises the cellist’s commitment and stylistic independence: “Anja has become part of the music without losing her own identity. -

All These Post-1965 Movements Under the “Conceptual Art” Umbrella

All these post-1965 movements under the “conceptual art” umbrella- Postminimalism or process art, Site Specific works, Conceptual art movement proper, Performance art, Body Art and all combinations thereof- move the practice of art away from art-as-autonomous object, and art-as-commodification, and towards art-as-experience, where subject becomes object, hierarchy between subject and object is critiqued and intersubjectivity of artist, viewer and artwork abounds! Bruce Nauman, Live-Taped Video Corridor, 1970, Conceptual Body art, Postmodern beginning “As opposed to being viewers of the work, once again they are viewers in it.” (“Subject as Object,” p. 199) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9IrqXiqgQBo A Postmodern beginning: Body art and Performance art as critique of art-as-object recap: -Bruce Nauman -Vito Acconci focus on: -Chris Burden -Richard Serra -Carolee Schneemann - Hannah Wilke Chapter 3, pp. 114-132 (Carolee Schneemann and Hannah Wilke, First Generation Feminism) Bruce Nauman, Bouncing Two Balls Between the Floor and Ceiling with Changing Rhythms, 1967-1968. 16mm film transferred to video (black and white, sound), 10 min. Body art/Performance art, Postmodern beginning- performed elementary gestures in the privacy of his studio and documented them in a variety of media Vito Acconci, Following Piece, 1969, Body art, Performance art- outside the studio, Postmodern beginning Video documentation of the event Print made from bite mark Vito Acconci, Trademarks, 1970, Body art, Performance art, Postmodern beginning Video and Print documentation -

Rhythm Bones Player a Newsletter of the Rhythm Bones Society Volume 10, No

Rhythm Bones Player A Newsletter of the Rhythm Bones Society Volume 10, No. 3 2008 In this Issue The Chieftains Executive Director’s Column and Rhythm As Bones Fest XII approaches we are again to live and thrive in our modern world. It's a Bones faced with the glorious possibilities of a new chance too, for rhythm bone players in the central National Tradi- Bones Fest in a new location. In the thriving part of our country to experience the camaraderie tional Country metropolis of St. Louis, in the ‗Show Me‘ state of brother and sisterhood we have all come to Music Festival of Missouri, Bones Fest XII promises to be a expect of Bones Fests. Rhythm Bones great celebration of our nation's history, with But it also represents a bit of a gamble. We're Update the bones firmly in the center of attention. We betting that we can step outside the comfort zones have an opportunity like no other, to ride the where we have held bones fests in the past, into a Dennis Riedesel great Mississippi in a River Boat, and play the completely new area and environment, and you Reports on bones under the spectacular arch of St. Louis. the membership will respond with the fervor we NTCMA But this bones Fest represents more than just have come to know from Bones Fests. We're bet- another great party, with lots of bones playing ting that the rhythm bone players who live out in History of Bones opportunity, it's a chance for us bone players to Missouri, Kansas, Illinois, Oklahoma, and Ne- in the US, Part 4 relive a part of our own history, and show the braska will be as excited about our foray into their people of Missouri that rhythm bones continue (Continued on page 2) Russ Myers’ Me- morial Update Norris Frazier Bones and the Chieftains: a Musical Partnership Obituary What must surely be the most recognizable Paddy Maloney. -

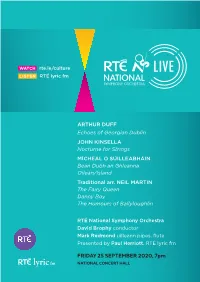

RTE NSO 25 Sept Prog.Qxp:Layout 1

WATCH rte.ie/culture LISTEN RTÉ lyric fm ARTHUR DUFF Echoes of Georgian Dublin JOHN KINSELLA Nocturne for Strings MÍCHEÁL Ó SÚILLEABHÁIN Bean Dubh an Ghleanna Oileán/Island Traditional arr. NEIL MARTIN The Fairy Queen Danny Boy The Humours of Ballyloughlin RTÉ National Symphony Orchestra David Brophy conductor Mark Redmond uilleann pipes, flute Presented by Paul Herriott, RTÉ lyric fm FRIDAY 25 SEPTEMBER 2020, 7pm NATIONAL CONCERT HALL 1 Arthur Duff 1899-1956 Echoes of Georgian Dublin i. In College Green ii. Song for Amanda iii. Minuet iv. Largo (The tender lover) v. Rigaudon Arthur Duff showed early promise as a musician. He was a chorister at Dublin’s Christ Church Cathedral and studied at the Royal Irish Academy of Music, taking his degree in music at Trinity College, Dublin. He was later awarded a doctorate in music in 1942. Duff had initially intended to enter the Church of Ireland as a priest, but abandoned his studies in favour of a career in music, studying composition for a time with Hamilton Harty. He was organist and choirmaster at Christ Church, Bray, for a short time before becoming a bandmaster in the Army School of Music and conductor of the Army No. 2 band based in Cork. He left the army in 1931, at the same time that his short-lived marriage broke down, and became Music Director at the Abbey Theatre, writing music for plays such as W.B. Yeats’s The King of the Great Clock Tower and Resurrection, and Denis Johnston’s A Bride for the Unicorn. The Abbey connection also led to the composition of one of Duff’s characteristic works, the Drinking Horn Suite (1953 but drawing on music he had composed twenty years earlier as a ballet score). -

National Endowment for the Arts Annual Report 1996

TO THE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES: It is my pleasure to transmit herewith the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts for the fiscal year 1996. One measure of a great nation is the vitality of its culture, the dedication of its people to nurturing a climate where creativity can flourish. By support ing our museums and theaters, our dance companies and symphony orches tras, our writers and our artists, the National Endowment for the Arts provides such a climate. Look through this report and you will find many reasons to be proud of our Nation’s cultural life at the end of the 20th century and what it portends for Americans and the world in the years ahead. Despite cutbacks in its budget, the Endowment was able to fund thou sands of projects all across America -- a museum in Sitka, Alaska, a dance company in Miami, Florida, a production of Eugene O’Neill in New York City, a Whisder exhibition in Chicago, and artists in the schools in all 50 states. Millions of Americans were able to see plays, hear concerts, and participate in the arts in their hometowns, thanks to the work of this small agency. As we set priorities for the coming years, let’s not forget the vita! role of the National Endowment for the Arts must continue to play in our national life. The Endowment shows the world that we take pride in American culture here and abroad. It is a beacon, not only of creativity, but of free dom. And let us keep that lamp brightly burning now and for all time. -

Dossier Ijin 6

Certains vous diront que l’imagination est un don, pour d’autres ce sera un art, pour d’autres encore, une forme d’évasion et un préliminaire à toutes formes de création. En pays Bigouden, danseurs et musiciens ont fait de l’imagination une priorité pour orchestrer leur nouveau spectacle : IJIN. Tout en respectant les styles et répertoires issus de leur culture traditionnelle, le Bagad CAP CAVAL et le cercle cel- tique AR VRO VIGOUDENN, deux ensembles à forte identité et aux savoir-faire reconnus se sont unis pour laisser courir leur imagina- tion par-delà les horizons de leur terroir. Au-delà de cette même passion pour la musique et la danse traditionnelles, ils partagent également une même approche de la scène et une vision identique du spectacle, tant dans l’écriture musicale et chorégraphique que dans la création et la reconstitu- tion de costumes. IJIN, c’est aussi l’imaginaire d'une rencontre avec d’autres univers musicaux comme celui du chanteur kabyle Farid Aït Sia- meur ou ceux de Yann Guirec Le Bars et Julien Le Mentec ou en- core celui des percussions de Dominique Molard. De toutes ces sources d’inspiration est né IJIN. Ouvrez gran- des les ailes de votre propre imagination et laissez vous porter… La musique et la danse feront le reste. Bagad Cap Caval « Cap Caval », ancien nom du Pays Bigouden, contrée de l’extrême sud-ouest de la Cor- nouaille, voilà le nom quelque peu sorti des mémoires, que Denis Daniel avait retenu en 1984 pour le bagad qu’il venait de créer sur PLOMEUR. -

Postmodern Art and Its Discontents Professor Paul Ivey, School of Art [email protected]

Humanities Seminars Program Fall 2014 Postmodern Art and Its Discontents Professor Paul Ivey, School of Art [email protected] This ten week course examines the issues, artists, and theories surrounding the rise of Postmodernism in the visual arts from 1970 into the twenty-first century. We will explore the emergence of pluralism in the visual arts against a backdrop of the rise of the global economy as we explore the “crisis” of postmodern culture, which critiques ideas of history, progress, personal and cultural identities, and embraces irony and parody, pastiche, nostalgia, mass or “low” culture, and multiculturalism. In a chronological fashion, and framed by a discussion of mid-century artistic predecessors Abstract Expressionism, Pop, and Minimal Art, the class looks at the wide-ranging visual art practices that emerged in 1970s Conceptual Art, Performance, Feminist Art and identity politics, art activism and the Culture Wars, Appropriation Art, Neo-expressionism, Street Art, the Young British Artists, the Museum, and Festivalism. Week 1: October 6 Contexts and Setting the Stage: What is Postmodernism Abstract Expressionism Week 2: October 13 Cold War, Neo-Dada, Pop Art Week 3: October 20 Minimalism, Postminimalism, Earth Art Week 4: October 27 Conceptual Art and Performance: Chance, Happenings, Arte Povera, Fluxus Week 5: November 3 Video and Performance Week 6: November 10 Feminist Art and Identity Politics Week 7: November 17 Street Art, Neo-Expressionism, Appropriation Week 8: December 1 Art Activism and Culture Wars Week 9: December 8 Young British Artists (YBAs) Week 10: December 15 Festivalism and the Museum . -

59Th Annual Critics Poll

Paul Maria Abbey Lincoln Rudresh Ambrose Schneider Chambers Akinmusire Hall of Fame Poll Winners Paul Motian Craig Taborn Mahanthappa 66 Album Picks £3.50 £3.50 .K. U 59th Annual Critics Poll Critics Annual 59th The Critics’ Pick Critics’ The Artist, Jazz for Album Jazz and Piano UGUST 2011 MORAN Jason DOWNBEAT.COM A DOWNBEAT 59TH ANNUAL CRITICS POLL // ABBEY LINCOLN // PAUL CHAMBERS // JASON MORAN // AMBROSE AKINMUSIRE AU G U S T 2011 AUGUST 2011 VOLUme 78 – NUMBER 8 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Managing Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Aaron Cohen Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Assistant Theresa Hill 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Michael Point, Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Or- leans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. -

Les Mondes Celtes

LES MONDES CELTES sélection de la Bibliothèque de Toulouse dans le cadre du festival Rio Loco 2016 Introduction 7 sommaire Qu’est-ce que les mondes celtiques ? 8 Racines et patrimoine 10 Bretagne 66 Musique ! 10 • Musique ! 66 Cultures vivantes 13 • Cultures vivantes 74 • Civilisations celtes 13 • Littératures et récits de voyage 75 • Religions 16 • Arts et cinéma 80 • Traditions et symboles 17 • Jeune public : 81 Littératures et récits de voyages 19 contes et découvertes • Récits de voyages 23 Europe et ailleurs 84 Arts et cinéma 24 Europe 84 Jeune public : 26 Espagne : Asturies et Galice 84 contes et découvertes Asturies 84 Royaume-Uni 30 • Musique ! 84 Écosse 30 Galice 85 • Musique ! 30 • Musique ! 85 • Cultures vivantes 36 • Cinéma 86 • Littératures et récits de voyage 37 Italie : Vallée d’Aoste 87 • Arts et cinéma 39 • Musique ! 87 • Jeune public : 40 Ailleurs en Europe 87 contes et découvertes • Musique ! 87 Île de Man 41 • Cultures vivantes 88 • Musique ! 41 • Jeune public : 89 • Cultures vivantes 41 contes et découvertes Pays de Galles 42 Ailleurs 89 • Musique ! 42 • Musique ! 89 • Cultures vivantes 44 • Littératures 92 • Littératures 44 Cornouailles 45 ZOOM SUR… • Musique ! 45 La cornemuse 11 • Jeune public : 47 Les langues celtiques 13 contes et découvertes Jean Markale 18 Irlande 48 La Légende arthurienne 19 • Musique ! 48 Ken Loach 63 • Cultures vivantes 57 Lexique 93 • Littératures et récits de voyage 58 Remerciements 99 • Arts et cinéma 61 • Jeune public : 63 contes et découvertes Introduction 7 sommaire Qu’est-ce que les -

Consultez L'article En

Dan ar Braz Retour sur soixante ans de guitare ll a sorti l’album Dans ar dañs en début d’année : une Mon père était carrossier à Quim- belle manière de fêter cinquante ans de carrière (et soixante per. Ma mère travaillait au secré- Kejadenn de guitare) qui l’ont vu porter haut les couleurs d’un folk tariat. C’est plutôt par devoir filial rock interceltique et en ont fait un des artistes majeurs de qu’il a repris l’affaire familiale mais la musique bretonne. Avec humilité et sincérité, Dan ar ce n’était pas ce à quoi il se desti- nait. Cela a joué un rôle, plus tard, Braz nous raconte son parcours. quand j’ai voulu faire de la musique en professionnel. Ma mère, qui e suis né dans un milieu où essayaient de copier) les Anglo- voulait m’en dissuader, a essayé on écoutait beaucoup de mu- saxons, la musique venant de la de convaincre mon père de m’en Jsiques, toutes sortes de mu- chambre de mon grand frère a empêcher mais il a dit : « Moi, j’ai siques. Mes parents n’étaient commencé à prendre sa place dans fait toute ma vie un métier qui ne pas musiciens à proprement dit, mon univers. Comme lui, je me suis me plaisait pas. Mes enfants feront mais mon père chantait extrême- mis à écouter Radio Luxembourg ce qu’ils veulent. » ment bien et on l’appelait Tino à qui était allemande le jour et an- J’ai donc commencé à étudier la cause de ses interprétations des glaise le soir. -

Acdsee Proprint

BULK RATE U.S. POSTAGE PAID Permit No. 2419 lPE lPITClHl K.C., Mo. FREE FREE VOL. II NO. 1 YOU'LL NEVER GET RICH READING THE PITCH FEBRUARY 1981 FBIIRUARY II The 8-52'5 Meet BUDGBT The Rev. in N.Y. Third World Bit List .ONTHI l ·TRIVIA QUIZ· WHAT? SQt·1E RECORD PRICES ARE ACTUALLY ~~nll .815 m wi. i .••lIIi .... lllallle,~<M0,~ CGt4J~G ·DOWN·?····· S€f ·PAGE: 3. FOR DH AI LS , prizes PAGE 2 THE PENNY PITCH LETTERS Dec. 29,1980 Dear Warren, Over the years, Kansas Attorney General's have done many strange things. Now the Kansas Attorney General wants to stamp out "Mumbo Jumbo." 4128 BROADWAY KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI 64111 Does this mean the "Immoral Minority" (816) 561·1580 will be banned from Kansas? Is being banned from Kansas a hardship? Edi tor ....••..•••.• vifarren Stylus Morris Martin Contributing vlriters this issue: Raytown, Mo. P.S. He probably doesn't like dreadlocks Rev. Dwight Frizzell, Lane & Dave from either. GENCO labs, Blind Teddy Dibble, I-Sheryl, Ie-Roths, Lonesum Chuck, Mr.D-Conn, Le Roi, Rage n i-Rick, P. Minkin, Lindsay Shannon, Mr. P. Keenan, G. Trimble, Jan. 26, 1981 debranderson, M. Olson Dear Editor, Inspiration this issue: How come K. C. radio stations never Fred de Cordova play, The Inmates "I thought I heard a Heartbeat", Roy Buchanan "Dr. Rock & Roll" Peter Green, "Loser Two Times", Marianne r,------:=~--~-__l "I don' t care what they say about Faithfull, "Broken English", etc, etc,? being avant garde or anything else. How come? Frankly, call me square if you want Is this a plot against the "Immoral to. -

A Nonesuch Retrospective

STEVE REICH PHASES A N O nes U ch R etr O spective D isc One D isc T W O D isc T hree MUSIC FOR 18 MUSICIANS (1976) 67:42 DIFFERENT TRAINS (1988) 26:51 YOU ARE (VARIATIONS) (2004) 27:00 1. Pulses 5:26 1. America—Before the war 8:59 1. You are wherever your thoughts are 13:14 2. Section I 3:58 2. Europe—During the war 7:31 2. Shiviti Hashem L’negdi (I place the Eternal before me) 4:15 3. Section II 5:13 3. After the war 10:21 3. Explanations come to an end somewhere 5:24 4. Section IIIA 3:55 4. Ehmor m’aht, v’ahsay harbay (Say little and do much) 4:04 5. Section IIIB 3:46 Kronos Quartet 6. Section IV 6:37 David Harrington, violin Los Angeles Master Chorale 7. Section V 6:49 John Sherba, violin Grant Gershon, conductor 8. Section VI 4:54 Hank Dutt, viola Phoebe Alexander, Tania Batson, Claire Fedoruk, Rachelle Fox, 9. Section VII 4:19 Joan Jeanrenaud, cello Marie Hodgson, Emily Lin, sopranos 10. Section VIII 3:35 Sarona Farrell, Amy Fogerson, Alice Murray, Nancy Sulahian, 11. Section IX 5:24 TEHILLIM (1981) 30:29 Kim Switzer, Tracy Van Fleet, altos 12. Section X 1:51 4. Part I: Fast 11:45 Pablo Corá, Shawn Kirchner, Joseph Golightly, Sean McDermott, 13. Section XI 5:44 5. Part II: Fast 5:54 Fletcher Sheridan, Kevin St. Clair, tenors 14. Pulses 6:11 6. Part III: Slow 6:19 Geri Ratella, Sara Weisz, flutes 7.