Downloaded From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soil Conservation and Poverty: Lessons from Upland Indonesia

Society and Natural Resources, Volume 7, pp. 429-443 0894-1920/94 $10.00+ .00 Printed in the UK. All rights reserved. Copyright © 1994 Taylor & Francis Soil Conservation and Poverty: Lessons from Upland Indonesia JILL M. BELSKY Department of Sociology University of Montana Missoula, Montana, USA Soil conservation efforts in Indonesia since the Dutch colonial era have focused on in- troducing bench terraces—a costly soil conservation method for poor, upland farm- ers. Data from two villages in the Kerinci uplands of Sumatra illustrate that even with state underwriting of bench terrace construction, farmers across all economic strata still resist using this method. Why the state has not pursued alternative soil conserva- tion approaches—especially ones that entail the "conservation farming " approach and that can better build upon the diversity of upland farming systems—is discussed in the context of the state's emphasis on productivist and commodity-led agricultural development and on broader geopolitical institutions and forces that perpetuate this approach. Given these constraints, state underwriting of soil conservation for poor farmers (i.e., providing "landesque capital" in Blaikie and Brookfield's 1987 termi- nology) suggests undue hope through economic remedies and the ability of the state to implement environmental and social reform, especially to benefit the poor. Keywords Indonesia, political ecology, political economy, poverty, soil conserva- tion, terraces Since the Dutch colonial era, soil conservation efforts in upland Indonesia have empha- sized the introduction of bench terraces. However, the long-term use of agricultural ter- racing by dryland farmers on sloping lands in Indonesia (as well as throughout Southeast Asia) has been varied and often hotly contested (Pelzer, 1945; Chapman, 1975). -

Flood Management in the Brantas and Bengawan Solo River Basins, Indonesia

Asian Water Cycle Symposium 2016 Tokyo, Japan, 1 - 2 March 2016 FLOOD MANAGEMENT IN THE BRANTAS AND BENGAWAN SOLO RIVER BASINS, INDONESIA Gede Nugroho Ariefianto, M. Zainal Arifin, Fahmi Hidayat, Arief Satria Marsudi Jasa Tirta Public Corporation http://www.jasatirta1.co.id Flood Hazards in the Brantas and Bengawan Solo River Basins • Flood continues to be the most severe annual disasters in the Brantas and Bengawan Solo River Basins, particularly in the tributaries of the Brantas River basin and the Lower Bengawan Solo River Basin. • The intensity of flood disasters appears to have increased during the past few years due to the impact of urbanization, industrialization, climate change and watershed degradation. • Floods in the Brantas and Bengawan Solo River Basins cause devastating losses to human lives and livelihoods, and also seriously impede economic development in East Java Province. Floods in the Brantas and Bengawan Solo River Basins in February 2016 Floods in the Brantas and Bengawan Solo River Basins in February 2016 Flood Control in the Brantas and Bengawan Solo River Basins • Prior to the 1990s, large-scale structural measures were adopted as structural measures for flood control in the basins. • The construction of major dam and reservoirs can lead to better regulation of the flow regime in mainstream of Brantas and Upper Bengawan Solo. • Development of large dams in the Bengawan Solo River basin for flood control encounter social and environmental problems. Flood Control Structures in the Brantas River Basin Flood Control Structures in the Bengawan Solo River Basin Flood Management in the Brantas and Bengawan Solo River Basins • Floods can’t be prevented totally in the Brantas and Bengawan Solo River Basins. -

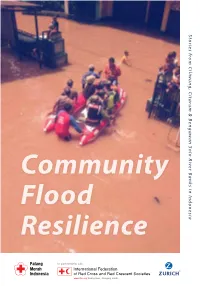

Community Flood Resilience

Stories from Ciliwung, Citarum & Bengawan Solo River Banks in Indonesia Community Flood Resilience Stories from Ciliwung, Citarum & Bengawan Solo River Banks in Indonesia Community Flood Resilience Stories from Ciliwung, Citarum & Bengawan Solo River Banks Publisher Palang Merah Indonesia (PMI) in partnership with Stories from Ciliwung, Citarum & Bengawan Solo River Banks in Indonesia International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) Zurich Insurance Indonesia (ZII) Palang Merah Indonesia National Headquarter Disaster Management Division Jl. Jend Gatot Subroto Kav. 96 - Jakarta 12790 Phone: +62 21 7992325 ext 303 Fax: +62 21 799 5188 www.pmi.or.id First edition March 2018 CFR Book Team Teguh Wibowo (PMI) Surendra Kumar Regmi (IFRC) Arfik Triwahyudi (ZII) Editor & Book Designer Gamalel W. Budiharga Writer & Translator Budi N.D. Dharmawan English Proofreader Daniel Owen Photographer Suryo Wibowo Infographic Dhika Indriana Photo Credit Suryo Wibowo, Budi N.D. Dharmawan, Gamaliel W. Budiharga & PMI, IFRC & ZII archives © 2018. PMI, IFRC & ZII PRINTED IN INDONESIA Community Flood Resilience Preface resilience/rɪˈzɪlɪəns/ n 1 The capacity to recover quickly from difficulties; toughness;2 The ability of a substance or object to spring back into shape; elasticity. https://en.oxforddictionaries.com iv v Preface hard work of all the parties involved. also heads of villages and urban Assalammu’alaikum Warahmatullahi Wabarakatuh, The program’s innovations have been villages in all pilot program areas for proven and tested, providing real their technical guidance and direction Praise for Allah, that has blessed us so that this solution, which has been replicated for the program implementors as well Community Flood Resilience (CFR) program success story in other villages and urban villages, as SIBAT teams, so the program can book is finally finished. -

Siluriformes, Pangasiidae)

PANGASIUS BEDADO ROBERTS, 1999: A JUNIOR SYNONYM OF PANGASIUS DJAMBAL BLEEKER, 1846 (SILURIFORMES, PANGASIIDAE) by Rudhy GUSTIANO (1,2), Guy G. TEUGELS †(2) & Laurent POUYAUD (3)* ABSTRACT. - The validities of two nominal pangasiid catfish species, Pangasius djambal and P. bedado were examined based on morphometric, meristic, and biological characters. Metric data were analysed using principal component analysis. Based on our results, we consider P. bedado as a junior synonym of P. djambal. RÉSUMÉ. - Pangasius bedado Roberts, 1999 : un synonyme junior de Pangasius djambal Bleeker, 1846 (Siluriformes, Pangasiidae). La validité de deux espèces nominales de poissons chats Pangasiidae, Pangasius djambal et P. bedado, a été examinée sur la base de caractères morphométriques, méristiques et biologiques. Une analyse en composantes principales a été appliquée sur les données métriques. Nos résultats nous amènent à considérer P. bedado comme synonyme junior de P. djambal. Key words. - Pangasiidae - Pangasius djambal - Pangasius bedado - Biometrics - Synonymy. Pangasiid catfishes are characterized by a laterally com- P. djambal. They distinguished it from other Pangasius spe- pressed body, the presence of two pairs of barbels, the pres- cies by the following characters: rounded or somewhat trun- ence of an adipose fin, dorsal fin with two spines (Teugels, cate (never pointed) snout, palatal teeth with two palatine 1996), and anal fin 1/5 to 1/3 of standard length (Gustiano, patches and a moderately large median vomerine patch (but 2003). They occur in freshwater in Southern and Southeast vomerine patch usually clearly divided into two in juve- Asia. Based on our osteological observations, this family niles), at least some specimens with a marked color pattern forms a monophyletic group diagnosed by: the os parieto- on body and fins, including two stripes on caudal lobes. -

Non-Spurious Correlations Between Genetic and Linguistic Diversities in the Context of Human Evolution

Non-Spurious Correlations between Genetic and Linguistic Diversities in the Context of Human Evolution Dan Dediu Bsc. Math. Comp. Sci., Msc. Neurobiol. Behav. A thesis submitted in fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy to Linguistics and English Language School of Philosophy, Psychology and Language Sciences University of Edinburgh February 2007 © Copyright 2006 by Dan Dediu Declaration I hereby declare that this thesis is of my own composition, and that it contains no material previously submitted for the award of any other degree. The work reported in this thesis has been executed by myself, except where due acknowledgment is made in the text. Dan Dediu iii iv Abstract This thesis concerns human diversity, arguing that it represents not just some form of noise, which must be filtered out in order to reach a deeper explanatory level, but the engine of human and language evolution, metaphorically put, the best gift Nature has made to us. This diversity must be understood in the context of (and must shape) human evolution, of which the Recent Out-of-Africa with Replacement model (ROA) is currently regarded, especially outside palaeoanthropology, as a true theory. It is argued, using data from palaeoanthropology, human population genetics, ancient DNA studies and primatology, that this model must be, at least, amended, and most probably, rejected, and its alternatives must be based on the concept of reticulation. The relationships between the genetic and linguistic diversities is complex, including inter- individual genetic and behavioural differences (behaviour genetics) and inter-population differences due to common demographic, geographic and historic factors (spurious correlations), used to study (pre)historical processes. -

The Mysterious Phylogeny of Gigantopithecus

Kimberly Nail Department ofAnthropology University ofTennessee - Knoxville The Mysterious Phylogeny of Gigantopithecus Perhaps the most questionable attribute given to Gigantopithecus is its taxonomic and phylogenetic placement in the superfamily Hominoidea. In 1935 von Koenigswald made the first discovery ofa lower molar at an apothecary in Hong Kong. In a mess of"dragon teeth" von Koenigswald saw a tooth that looked remarkably primate-like and purchased it; this tooth would later be one offour looked at by a skeptical friend, Franz Weidenreich. It was this tooth that von Koenigswald originally used to name the species Gigantopithecus blacki. Researchers have only four mandibles and thousands ofteeth which they use to reconstruct not only the existence ofthis primate, but its size and phylogeny as well. Many objections have been raised to the past phylogenetic relationship proposed by Weidenreich, Woo, and von Koenigswald that Gigantopithecus was a forerunner to the hominid line. Some suggest that researchers might be jumping the gun on the size attributed to Gigantopithecus (estimated between 10 and 12 feet tall); this size has perpetuated the idea that somehow Gigantopithecus is still roaming the Himalayas today as Bigfoot. Many researchers have shunned the Bigfoot theory and focused on the causes of the animals extinction. It is my intention to explain the theories ofthe past and why many researchers currently disagree with them. It will be necessary to explain how the researchers conducted their experiments and came to their conclusions as well. The Research The first anthropologist to encounter Gigantopithecus was von Koenigswald who happened upon them in a Hong Kong apothecary selling "dragon teeth." Due to their large size one may not even have thought that they belonged to any sort ofprimate, however von Koenigswald knew better because ofthe markings on the molar. -

Homo Erectus Foodways

Homo Erectus Foodways ENVIRONMENT 3 RAINFOREST 4 OUT OF AFRICA 4 DIFFERENT ENVIRONMENTS 5 MORPHOLOGY & LOCOMOTION 7 Did Homo Erectus still sleep in the trees? 11 CAPTURE 14 TEETH AND JAW 15 C3/C4 ANALYSIS 16 HOARDING 21 ANIMAL FOODS 21 HUNTING AND SCAVENGING 22 HUNTING METHODS 29 SEAFOOD 35 SUMMARY 37 PROCESSING & INGESTION 38 TOOLS 38 THROWN TOOLS 41 BUTCHERY 43 PLANT TOOLS 44 DENTAL ADAPTATIONS 44 MICROWEAR 46 COOKING 51 FIRE 53 COOKING SUMMARY 60 COOKED VS RAW CONSUMPTION 60 FERMENTED FOODS 61 COOKING TECHNOLOGIES 61 COOKING STARCHES 62 COOKING PROTEINS 64 COOKING FATS 67 VITAMINS AND MINERALS 69 PLANT DEFENSES 70 DIGESTION 70 METABOLISM 73 EXPENSIVE TISSUE HYPOTHESIS 74 NUTRIENTS FOR ENCEPHALIZATION 75 PROTEIN 77 CARBOHYDRATES 81 INTELLIGENCE 81 SOCIAL DYNAMICS 83 CULTURE 86 MATING & CHILD REARING 87 LIFE HISTORY 91 GROUP SIZE 93 SEXUAL DIMORPHISM 93 DIVISION OF LABOR 95 FOOD SHARING 98 CHIMPS 98 CULTURE 101 CARE FOR OTHERS 102 References 103 HOMO ERECTUS Extinction of Early Homo, Homo Rudolfensis & Habilis, and the Emergence of Erectus Around two million years ago, another hominid emerged in Africa called Homo Erectus that survived for over one million years, becoming extinct only about one hundred and fifty thousand years ago. At the beginning of its existence, it evidently co-existed with both Homo Hablis and Rudolfensis, as well as Australopithecus Boisei and at the end of its time, it overlapped with itself, Homo Sapien. In any case, soon after its emergence, Homo Habilis and Rudolfensis went extinct; at least that is what we have concluded based on our limited number of fossils. -

Anthropological Science 110(2), 165-177, 2002 Preliminary

Anthropological Science 110(2), 165-177, 2002 Preliminary Observation of a New Cranium of •ôNH•ôHomoerectus•ôNS•ô (Tjg-1993.05) from Sangiran, Central Jawa Johan Arif1, Yousuke Kaifu2, Hisao Baba2, Made Emmy Suparka1, Yahdi Zaim1, and Takeshi Setoguchi3 1 Department of Geology, Institute of Technology Bandung, Indonesia 2 Department of Anthropology , National Science Museum, Tokyo 3 Department of Geology and Mineralogy , Faculty of Science, Kyoto University, Kyoto (Received October 5, 2001; accepted February 13, 2002) Abstract In May of 1993, a new well-preserved hominid skull was recovered from the Bapang (Kabuh) Formation of the Sangiran region, Central Jawa. In this paper, we provisionally describe the skull and compare it with •ôNH•ôHomo erectus•ôNS•ô.crania from Jawa and China. The new skull possesses a series of characteristic features of Asian •ôNH•ôH.erectus•ôNS•ô in overall size and shape of the vault, the expression of various ectocranial structures, and other details. Among three geographical and chronolog icalsubgroups of Asian •ôNH•ôH.erectus•ôNS•ô, the new skull shows affinities with the Jawanese Early Pleistocene subgroup (specimens from the Sangiran and Trinil regions), as expected from its provenance. •ôGH•ô Keywords•ôGS•ô: •ôNH•ôHomo erectus•ôNS•ô,human evolution, Indonesia, paleoanthropology Introduction In May of 1993, a new hominid skull of an adult individual was recovered from the Sangiran area, Central Jawa (Figs. 1 and 2). There is no formal specimen number for this skull. Sartono called it Skull IX, and Larick et al. (2001) provisionally la beledit as Tjg-1993.05. The discovery of the skull was first announced in academic meetings in the Netherlands (Sartono et al, 1995), Indonesia (Sartono and Tyler, 1993), and America (Tyler et al., 1994). -

Relevance of Aquatic Environments for Hominins: a Case Study from Trinil (Java, Indonesia)

Journal of Human Evolution 57 (2009) 656–671 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Human Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jhevol Relevance of aquatic environments for hominins: a case study from Trinil (Java, Indonesia) J.C.A. Joordens a,*, F.P. Wesselingh b, J. de Vos b, H.B. Vonhof a, D. Kroon c a Institute of Earth Sciences, VU University Amsterdam, De Boelelaan 1056, 1051 HV Amsterdam, The Netherlands b Naturalis National Museum of Natural History , P.O. Box 9517, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands c School of Geosciences, The University of Edinburgh, West Mains Road, Edinburgh EH9 3JW, UK article info abstract Article history: Knowledge about dietary niche is key to understanding hominin evolution, since diet influences body Received 31 December 2008 proportions, brain size, cognition, and habitat preference. In this study we provide ecological context for Accepted 9 April 2009 the current debate on modernity (or not) of aquatic resource exploitation by hominins. We use the Homo erectus site of Trinil as a case study to investigate how research questions on possible dietary relevance of Keywords: aquatic environments can be addressed. Faunal and geochemical analysis of aquatic fossils from Trinil Hominin evolution Hauptknochenschicht (HK) fauna demonstrate that Trinil at w1.5 Ma contained near-coastal rivers, lakes, Strontium isotopes swamp forests, lagoons, and marshes with minor marine influence, laterally grading into grasslands. Freshwater wetland Marine influence Trinil HK environments yielded at least eleven edible mollusc species and four edible fish species that Stingray could be procured with no or minimal technology. We demonstrate that, from an ecological point of Fish view, the default assumption should be that omnivorous hominins in coastal habitats with catchable Molluscs aquatic fauna could have consumed aquatic resources. -

PK-GWA Final Report

KNKT/02.02/06.01.33 NNAATTIIOONNAALL TTRRAANNSSPPOORRTTAATTIIOONN SSAAFFEETTYY CCOOMMMMIITTTTEEEE AIRCRAFT ACCIDENT REPORT PT. Garuda Indonesia GA421 B737-300 PK-GWA Bengawan Solo River, Serenan Village, Central Java 16 January 2002 NATIONAL TRANSPORTATION SAFETY COMMITTEE DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATIONS REPUBLIC OF INDONESIA 2006 When the Committee makes recommendations as a result of its investigations or research, safety is its primary consideration. However, the committee fully recognizes that the implementation of recommendations arising from its investigations will in some cases incur a cost to the industry. Readers should note that the information in NTSC reports is provided to promote aviation safety: in no case is it intended to imply blame or liability. This report has been prepared based upon the investigation carried out by the National Transportation Safety Committee in accordance with Annex 13 to the Convention on International Civil Aviation, UU No.15/1992 and PP No. 3/2001. This report was produced by the National Transportation Safety Committee (NTSC), Gd. Karsa Lt.2 Departemen Perhubungan dan Telekomunikasi, Jalan Medan Merdeka Barat 8 JKT 10110 Indonesia. Readers are advised that the Committee investigates for the sole purpose of enhancing aviation safety. Consequently, Committee reports are confined to matters of safety significance and maybe misleading if used for any other purpose. As NTSC believes that safety information is of greatest value if it is passed on for the use of others, readers are encouraged to copy or -

Homo Erectus: a Bigger, Faster, Smarter, Longer Lasting Hominin Lineage

Homo erectus: A Bigger, Faster, Smarter, Longer Lasting Hominin Lineage Charles J. Vella, PhD August, 2019 Acknowledgements Many drawings by Kathryn Cruz-Uribe in Human Career, by R. Klein Many graphics from multiple journal articles (i.e. Nature, Science, PNAS) Ray Troll • Hominin evolution from 3.0 to 1.5 Ma. (Species) • Currently known species temporal ranges for Pa, Paranthropus aethiopicus; Pb, P. boisei; Pr, P. robustus; A afr, Australopithecus africanus; Ag, A. garhi; As, A. sediba; H sp., early Homo >2.1 million years ago (Ma); 1470 group and 1813 group representing a new interpretation of the traditionally recognized H. habilis and H. rudolfensis; and He, H. erectus. He (D) indicates H. erectus from Dmanisi. • (Behavior) Icons indicate from the bottom the • first appearance of stone tools (the Oldowan technology) at ~2.6 Ma, • the dispersal of Homo to Eurasia at ~1.85 Ma, • and the appearance of the Acheulean technology at ~1.76 Ma. • The number of contemporaneous hominin taxa during this period reflects different Susan C. Antón, Richard Potts, Leslie C. Aiello, 2014 strategies of adaptation to habitat variability. Origins of Homo: Summary of shifts in Homo Early Homo appears in the record by 2.3 Ma. By 2.0 Ma at least two facial morphs of early Homo (1813 group and 1470 group) representing two different adaptations are present. And possibly 3 others as well (Ledi-Geraru, Uraha-501, KNM-ER 62000) The 1813 group survives until at least 1.44 Ma. Early Homo erectus represents a third more derived morph and one that is of slightly larger brain and body size but somewhat smaller tooth size. -

The History of Prehistoric Research in Indonesia to 1950

The History of Prehistoric Research in Indonesia to 1950 Received 16 January 1968 R. P. SOE]ONO INTRODUCTION HE oldest description of material valuable for prehistoric recording in future times was given by G. E. Rumphius at the beginning of the eighteenth century. Rum T phius mentioned the veneration of historical objects by local peoples, and even now survivals of the very remote past retain their respect. On several islands we also notice a continuation of prehistoric traditions and art. Specific prehistoric relics, like many other archaeological remains, are holy to most of the inhabitants because of their quaint, uncommon shapes. As a result, myths are frequently created around these objects. An investigator is not permitted to inspect the bronze kettle drum kept in a temple at Pedjeng (Bali) and he must respect the people's devout feelings when he attempts to observe megalithic relics in the Pasemah Plateau (South Sumatra); these facts accentuate the persistence oflocal veneration even today. In spite of the veneration of particular objects, which in turn favors their preservation, many other relics have been lost or destroyed through digging or looting by treasure hunters or other exploiters seeking economic gain. Moreover, unqualified excavators have com pounded the problem. P. V. van Stein Callenfels, originally a specialist in Hindu-Indonesian archaeology, be came strongly aware of neglect in the field of prehistoric archaeology, and he took steps to begin systematic research. During his visit to kitchen middens in East Sumatra during a tour of inspection in 1920 for the Archaeological Service, he met with the digging of shell heaps for shell for limekilns.